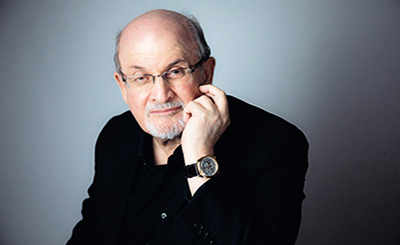

Robin Gupta. Photo: Shireen Quadri

Robin Gupta on his life dedicated to civil service, arts and literature

Robin Gupta, 69, joined the Indian Administrative Service in 1974. His deputations included challenging assignments throughout the country, including West Bengal, Haryana, Madhya Pradesh and Punjab. He was posted as commissioner on seven separate occasions, a record in the history of Indian civil service. His final posting before retirement was as financial commissioner, Government of Punjab.

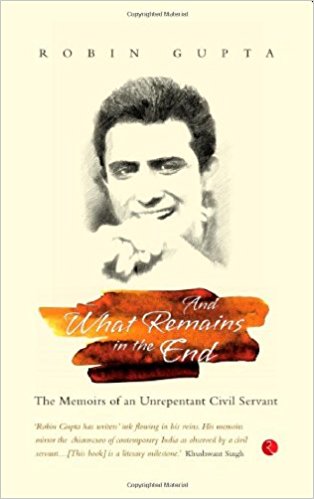

In What Remains in the End: The Memoirs of an Unrepentant Civil Servant (Rupa, 2013), Gupta chronicles the reminiscences of 37 years in the civil service. A critique of babudom, the book brings together the ruminations of an officer who was like an anomaly largely due to his pedigree and upbringing. While the world around him remained mired in greed, depravity, petty politics and power play, Gupta refused to bow to the pressures of the powers-that-be and strove to pass orders on merit. As a result, his political bosses were not too pleased and left him to cool his heels in insignificant postings.

Gupta, who has led a life devoted to the arts, in this interview, talks about his cushioned background, the grace of the world he comes from, the years that “passed” him by, his new book — on the aftermath of the British Raj in Delhi during which old families slowly got destroyed — and more. Excerpts from the interview:

The Punch: Your memoir, What Remains in the End, is the story of a life lived richly and on one’s own terms. Was the objective of the memoir to chronicle the contribution of the IAS in the evolution and growth of the country?

Robin Gupta: Basically, the book is a record of disappointments. I joined the service for its prestige and also because my mother was very keen that I should join. Her brother had topped the Indian Civil Service in 1930. Her father was the commissioner of Lahore who retired in 1913 with the title of Rai Bahadur. That takes it back to almost 135 years and it was almost a family compulsion that I join the IAS. Why I joined was basically to do something in this country. I didn’t know much because I had a very sheltered childhood. So, I first joined the Indian Police Service (IPS) because I was very young. Gradually, I realised that police was not my calling because it’s very linear to find out what is wrong everywhere. The scope of the IAS was to develop. So, I again wrote the exam and got selected, in the understanding that for 200 years or so the ICS and IAS had richly contributed in holding together this country, whether you’re in Assam or Tamil Nadu or in Gujarat, wherever you are, the same administrative structure is there to see. There are districts and sub-divisions, there are secretariats and departments and clearly demarcated duties which the British rulers left behind and which worked very well because there was law and order and revenue collection though not much of development. It was possible because there was no political guidance or interference; things were done according to law. So, when I joined in 1972, I had that image in mind. And, of course, I was fascinated by the prestige that was attached to it.

The Punch: You write about a series of events that let you down, but at the same time, they gave you a sense of where we were heading as a society and as a nation.

Robin Gupta: In my time, I saw it as a catastrophe because the divide between the very rich and the poor was widening under the socialist agenda. But, looking at it now, it’s far worse because it is like a country divided against itself, with Muslim population completely separated from the Hindu population, owing to the political mandate from the ruling party, which was not the case at all earlier. I remember, as a magistrate, if there was a law and order problem owing to communal disturbance, we straight away arrested five Muslims and five Hindus under executive sections of law. We told them that unless they came to terms with each other, they were going to remain inside. So, we never thought in terms of religion at that time.

The Punch: The mix of corruption with communalism is something that is threatening the idea of India today. How visible were such divides before Independence?

Robin Gupta: In the British times, there was no communalism as such: There were the rulers and the ruled. And the British did develop India. A lot of development, however, was because they wanted to extract its resources. Later, there was also some affection that got built up between the British and the Indians. They did so much to recover Sanskrit language and to save the Taj Mahal. They were great scholars and they were very objective.

The Punch: After the Independence, Partition further deepened the wounds between the two communities. While some leaders were trying to bridge that gap, this has only become worse. Do you think it’s largely been due to the political dispensations that we have had during these years?

Robin Gupta: Only because of that. It’s not possible for political leaders to by and large do the right things. They are elected by certain people to get their work done for those people, mostly through short cuts. There is no reason for these political people to be there because there are rules, there are officers and there’s the Parliament. If there’s a job to be done, an application is to be made to the officers and, according to law, the work will be done. Political forces look after the vote bank. They can only do it by bypassing officers, cutting short procedures and getting a job done in any manner possible, including directing the police or their magistrates to get rid of someone to ruin him in any manner possible.

The Punch: You have written so much about your mother. Tell us about the bond you shared with her.

Robin Gupta: I had mixed parentage. My mother was a Punjabi from Amritsar and Lahore. She belonged to a very old aristocratic family. My father was from the Eastern India who settled in Banaras and also belonged to a very old landed family. He was sent to study in England in his twenties. Unfortunately, he died of Parkinson’s. I was a child of old age. Both my parents were over 40 when I was born. My father died young and what remained was my mother. Relatives were not very friendly because there was Punjab on the one side and Eastern India on the other side. The only person I could turn to was her. She was a towering personality, very erudite, educated. An agnostic, she had no time for religion or rituals. She looked at things as they were. She was a scholar of Persian. She spoke beautiful English and, above all, called a spade a spade. People called her Lady sahib. A friend of the Viceroy’s wife, she used to go horse-riding with her.

The Punch: How was Punjab in the later years of your service? Have things changed now?

Robin Gupta: You will not find the high degree of profligacy, corruption and crudity anywhere else as in Punjab. Though one cannot generalise, by and large, people there like to show off. There is this understanding that a person can also not want to progress. If a person is poor, it’s unforgivable in Punjab. I found Bengal very civilised. I also served as magistrate in-charge of Siliguri. While in Bengal, there was only 6 per cent rural electrification, Punjab and Haryana had 100 per cent. There was extreme poverty in Bengal, but great beauty in relationships.

The Punch: You were in service for three and a half decades. What memories do you have of your life as a civil servant?

Robin Gupta: My last posting was as Financial Commissioner Revenue (FCR). It is a position equal to the Chief Secretary (CS). If the CM doesn’t like someone and doesn’t want to make him the CS, he makes him FCR. In British time, it was a big thing because everything depended on land revenue. After them, there was no land revenue. So, it’s like getting a big kick upstairs. You have a big flag and your own Secretariat. You’re the only person who has the right to be addressed as Your Honour. You sit in the highest revenue court.

During my last posting, I had to deal with the land revenue cases of the whole state, appointing, dismissing authority for tehsildars. I would put in my remark for the local police, but the ultimate job was to decide land revenues. With one stroke of the pen, I could move hundreds of crores. I studied the file very assiduously. The files used to be tied in red cloths. Nobody could touch them. I would bring them at night, make notes and sit in the court after all the preparation. Hundreds of lawyers would wait outside. Just as the court was starting, a sardarji would come and whisper, “aye Badal saheb likheya hai, ai haq wich karnede, ai khilaaf karne hai.” (The CM has said these cases are in favour and these are against.) I was aghast. There was an ICS officer called Mr Fletcher. When a chief minister sent such a request, he issued orders for the arrest of the CM on the pretext of contempt of court. So I didn’t bother at all about what the CM said.

After that last posting, my 37-year-long career came to an end. I did the cases as I wanted to, what I thought was right. Subsequently, the IAS officers have become worse than politicians. They teach them how to — and from where — extract money. Today, the political forces are undermining the entire structure of the government. Not only are they applying force from below, they are trying to influence from the top. Then they are trying to undermine the strength of the officer from below. So, today, a time has come in Punjab that every SHO is being transferred by the CM. Poor SP! What role does he have left? They have turned the government into a rubber stamp. This is what my book is about. In the book, comedy and tragedy have the same route. I wrote it as a legatee. It’s my survivor.

The Punch: You have written about some royal families and friends in great details. Tell us about your relationship with the royalties.

Robin Gupta: After Bahadur Shah Zafar died and after British came here and took full charge, the crown assumed the responsibility of governing India in 1858. Mughals ruled India. British looted India but, in the process, they built a structure to loot it better. There were certain small princely kingdoms and some very large ones. In Rajasthan, there were big kingdoms. Punjab had smaller ones. So, about two fifths of India was under the princes and the rest of India was under the paramount power. Under the British, even the princes were ruled through an ICS officer who would sit next to them in a throne and was called the resident, the political agent. So, the British encouraged the eccentricity, the perversion, profligacy and pusillanimous behaviour of the princes — women, wine and marriages of the dogs etc. They would not allow them to govern. There were good princes who wanted to govern, but the British wouldn’t allow them. They made them eccentric with drinks and shikars, but if they rebelled against the crown, the agent ICS would send a report and he’d be removed from the gaddi and replaced by another member of the royal family unless it was abolished. So, by the time I was a child in 1948, the feudal order continued in India. The British were still here and many officers continued here. Two of the naval chiefs were still British after the British left. And all of us were sent to similar schools. British India had two streams — (i) the army because the British were ruling on the strength of the army and the (ii) ICS who governed. One thousand ICS officers ruled the whole British Empire in the name of the queen. And their word was law. Then came the army and then the princes. So, when princes saw that they were losing their powers as the Independent movement started, they started marrying into the civil services. For instance, the father-in-law of the present Maharaja of Patiala was the Chief Secretary of Punjab. His two aunts were married to officers in the Foreign Service. So, they continued their power in this manner. When I was growing up, I had many such men and women (many of whom later became ICS officers) who went to the same club, supper parties, moonlight picnics and ballroom dance. I knew all the ruling families. I had a long relationship with Faridkot princesses for 17 long years.

The Punch: You had a very cushioned background. During your service, did you get a sense that your background worked against you?

Robin Gupta: The greatest good that was done for the public was by the British civil servants and police officers. Every human being has some feeling within him for another human being. A Deputy Commissioner or and SP in a lonely district sees the sorrow around. I wanted to do the things that I did partly because of my own nature. I did it more because of my lonely existence. My privilege helped me vis-à-vis the other officers who were busy making money. Because I had property and estate standing behind me, when I came there to work, what I was seeking was the majesty and splendour of office. I sought the pleasure of doing as much good work as I could, but I didn’t have to bother about the money. It never came my way. It strengthened me in my ability to do the right thing.

The Punch: Tell us about your appreciation of various forms of art.

Robin Gupta: I’m a trained musician. I received my training in Hindustani classical vocalist music from Ustad Shareef Nizami. I am inclined more toward arts. It’s an inner calling.

The Punch: One of the objectives to write this book was to mirror India and talk about its moral and ethical degradation that you saw at that point of time. Now, it has become much worse and we are perhaps heading towards bigger disasters. Are you disappointed with today’s India? What hope does the country hold on to?

Robin Gupta: When I was in service, my disappointment emanated from the fact that I could do nothing. Imagine a person who had a flag on his car for 18 years, was in service for 37 years, but was still unable to do anything! What a tragedy! However, I did achieve something by making the national sports policy. When I was the health secretary in Haryana, I told the CM to privatise all government hospitals. Government has all the best properties along the highway. I asked them to give them to private parties. They’ll run the hospitals while the government’s share is the property itself. The disappointment persisted in every department, including forest. There’s corruption and if officers want to do anything productive, they are transferred. I resigned three times. However, in my time, there were no alternative. But the hope of doing something lingered. The 40 years seem to have passed me by. Today, politicians have no vision for the country. They are arrogant and just looting the country.

The Punch: What is your new book about?

Robin Gupta: The new book is about the aftermath of the British Raj in Delhi and how the old families slowly got destroyed, the kind of eccentricities and lifestyles and so on. It will be a mirror to the way all of us lived and the strong point about that time was that nobody talked about communalism or religion. People were deeply interested in art, in music and in the fine arts and dance, in good friendship and cheer. Communalism and religious hatred were not a part of our social fabric at all. These are all families left behind by the British Raj, who had the similar education and similar childhood and the kind of life as it used to be in Lutyens’ Delhi.

The Punch: Are you filled with a sense of loss at the world which has disappeared — a world with a specific set of values and compassion?

Robin Gupta: It was a very graceful world where the cementing force was the arts. Now, when I see the rough edges of hatred, I long for the unity that used to be then. People led lives devoted to music. Singers like Begum Akhtar used to frequent our house. Talks revolved around art, culture, cuisine and good manners. It is a world that has gone away very rapidly.

The Punch: What sort of literature are you interested in?

Robin Gupta: The Brothers Karamazov by Fyodor Dostoyevsky influenced me a lot. It is about the great stark tragedy of the human condition. Among poets, I liked Constantine P. Cavafy. Among musicians, Begum Akhtar has been a favourite.

The Punch: How do you spend your time these days and what are the things you like to do?

Robin Gupta: I teach some poor children — four of them. I work for an NGO called Arpana. I read a lot, write a lot. I’m currently the Principal Advisor of Valley of Words: International Literature and Arts Festival which was held in November in Dehradun. I do a lot of travelling and gardening. I keep miles away from government and politics.

The Punch: Please share the broader vision behind the Valley of Words: International Arts and Literature Festival. It is believed that the choice of city to hold a literary festival plays a crucial role in its success. Do you ascribe to this view?

Robin Gupta: The Valley Of Words festival has been planned at Dehradun to reach a wide audience with the object of bringing into focus the rare literary talent and artistic expression of Uttarakhand that had been in the shadows of neglect for long years. The festival aims at better dovetailing local talent with the mainstream literary resurgence in India and to make art and creative writing the vehicle for social awareness for the need to change retrogressive mindsets to enable this beautiful part of India to step into the modern age, while drawing from the country’s richly textured history.

Comments

*Comments will be moderated