Prayaag Akbar in New Delhi recently. Photo: The Punch

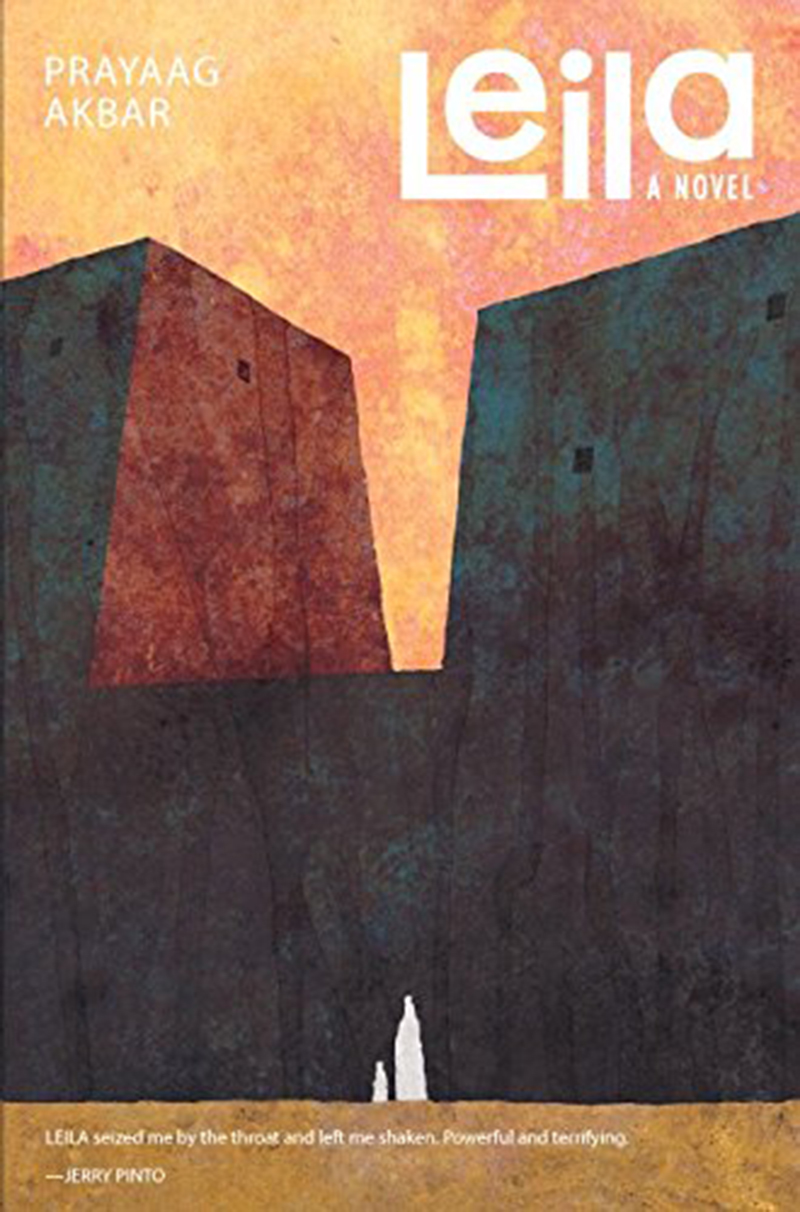

Prayaag Akbar’s debut novel, Leila, is a work of fiction, but it has chilling parallels with the dark and deeply disturbing social and political absurdities of our time. Its dystopian future is too much embedded in the now to seem distant

“Everyone tucked behind walls of their own making, stewing in a private shame…They can’t come out into the open. Anyone who can afford it hides behind walls. They think they are doing it for security, for purity, but somewhere it’s shame at their own greed,” reflects Shalini, the protagonist of Prayaag Akbar’s terrific and terrifying debut novel, Leila, while describing the city where walls have sprung up to divide and confine communities, in a series of (imaginary?) conversations with her former husband, Rizwan (or Riz) on a bus lurching through leafy streets.

Leila, published by Simon & Schuster India, the story of a mother’s search for her daughter she lost 16 years ago, is a haunting examination of class and privilege and draws up a scenario in which “the Slummers”, those living in slums, become part of the Council, run by the new political class that controls the city, aided by “Repeaters” who are on the prowl to create walls and wedges between communities. Determined upon segmentation, their favourite recourse is — “Purity for All.” Sample this fraction of a speech that Joshi, an influential figure in the new political system, proffers at a rally: “We must live according to our own great principles. Our history. Why must we live with compromise? Our purity has been perverted over the centuries. Centuries of rule by outsiders has led to spiritual subjugation. But the atrocities of this age can be combated. They are nothing but a passing phase. Our cultural roots are too firm. They are deeply struck into the spring of immortality. Now we once again find that purity, the purity that comes from order, from respect, from each of us remembering our communities. Our roles. What runs in our blood.”

Leila is a work of fiction, but it has chilling parallels with the dark and deeply disturbing social and political absurdities of our time. Its dystopian future is too much embedded in the now to seem distant. “It feels like what is going around us caught up with my imagination,” says Prayaag, who has examined the various aspects of marginalisation in India in his journalistic pieces. Excerpts from an interview:

THE PUNCH: How long has Leila been in the making? What did you want it to be? What did you draw on?

PRAYAAG AKBAR: I have been working on it for quite a while. Sometimes, it feels like what is going around us caught up with my imagination. I wanted to write about these huge political changes that take place in our society above our heads — that can go on in any society — and how they can really have a devastating, meaningful impact on someone’s life. I wanted to try and capture how some things are beyond your control when the society moves in a certain direction. At a certain moment, while nationalism or some other agenda is being pushed, what goes on is on the top of people’s mind and can have tremendous impact on them.

THE PUNCH: A great deal of what goes on in the novel already seems to be happening around us. Could one still say it’s a dystopian novel set in the future?

PRAYAAG AKBAR: People have asked me if it’s set in the future or in the past. I don’t really want to answer that question because it’s not important to the story. I’m not writing about how technology is moving. So, the time relevance is not important. For me, there are other important elements in the story. In my conceptualisation, it wasn’t that I’m writing a novel about the near future or about the future. How people read it is up to them.

THE PUNCH: While the novel is essentially about a mother’s quest for her daughter, it is also about the union of two individuals from diverse religious backgrounds and the price they have to pay for their choice. Did you want to explore the dynamics of such a family?

PRAYAAG AKBAR: We assume that we are heading towards a future that’s more equal and safer for people who are more enlightened. That’s not true at all. We have seen it throughout the world that there’s no constant path towards enlightenment. It’s very back-and-forth kind or going around in circles. The book is not about love jihad. These things predate that: even before love jihad, there was love marriage, inter-caste marriages. In India, there is so much politics around it and I wanted to examine that in whatever way I could. It’s again the fear around demographics and I tried to show in this book that it’s not that simple. People generally talk about marrying in the same caste to preserve the community, to keep them safe. But there are implications to it.

Sometimes, it seems to me that there is kind of war on affection and love and how that plays out is that women are targeted. Because we invest so much of male pride, the woman’s sexual integrity is a proxy for a male ego; the notion of male honour is so important. So, I wanted to show the link between the male honour and the female body in India. And it’s like a war on love and war on women. These ideas are very alien to me and I’ve always struggled with them. I’m from mixed parentage — my mother is a Christian and my father is a Muslim — so, I’ve always been interested in this dynamics.

THE PUNCH: But, at many levels, the novel is also about class and privilege. It draws up the scenario of a deeply segmented society in which those on the margins have taken over the reins of the city while those born into privilege are segregated, sidelined, subjugated — divested of dignity by those who are hell bent on creating a society with rules, boundaries and walls.

PRAYAAG AKBAR: That is exactly what the book is about. In India, there’s this assumption that since we are born into a certain privileged class, because of our education and family background, we are always going to remain at that level, that things are only going to get better, not so bad that I’ll end up in a slum. There is an assumption that there will be some kind of safety net. In India, one thinks that no matter how badly he has screwed up his life, something is going to save him from abject poverty. This is something that you don’t see in the West. In India, there are family and community safety nets that keep people afloat in the privilege they are accustomed to and I wanted to write about how in a society that wasn’t true anymore what happens to a person. Not only Shalini loses her wealth and privilege, she loses access to everything that can save her. She is not able to turn to anyone. If you know that injustice has been done to you, who do you go to for justice? Suddenly, she can’t go to anyone and that’s something I wanted to talk about.

Page

Donate Now

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated