Charlie Redmayne, CEO of HarperCollins UK, is also responsible for its India business. He first joined HarperCollins as Group Digital Director in 2008. He was promoted to Chief Digital Officer, based in HarperCollins’ head office in New York. He left HarperCollins in 2011 to set up Pottermore, J K Rowling’s digital publishing business, before returning as CEO in 2013.

At the start of his career, Redmayne served for four years as a lieutenant in the Irish Guards. He founded and ran the media buying company RCL Communications and entertainment business Blink TV, before launching leading UK teen internet company Mykindaplace Ltd in 2000, which he sold to BSkyB.

Half-brother of Oscar-winning actor Eddie Redmayne, he took over as HarperCollins UK CEO in 2013 after Victoria Barnsley, who founded 4th Estate and ran HarperCollins for 13 years, stepped down.

Redmayne, who was in New Delhi recently, spoke to The Punch about a whole host of issues — from publishing strategies in the UK and India to consolidation, digital publishing, e-rights management, data analytics, acquisitions, challenges from Amazon, his predecessor Victoria Barnsley who founded Fourth Estate, his love for cricket (he says he is quite fascinated by Virat Kohli’s style whom he finds an extraordinary player), his half-brother Eddy and lots more. Two key areas HarperCollins in India will focus more on in the future include commercial publishing and children’s books, Redmayne said.

Excerpts from an interview:

NAWAID ANJUM: How does HarperCollins look at the Indian market? What are your key focus areas?

CHARLIE REDMAYNE: The Indian market is an emerging market for books which is hugely exciting for a publishing company because the growth opportunity is significant. Historically, the focus of Indian publishing has very much been on great literary fiction, serious non-fiction, classical books, business books, historical books. There are about 60 odd books a year published with “India” in the title, looking at the political situations and the business world in India. Those books remain as important as ever and that market remains as important as ever. But opening up now is this huge commercial opportunity — commercial fiction, cheaper paperbacks, non-fiction, romance, crime and the like. The opportunity is to expand our publishing business. So, what we are doing is focusing just on the things that we have always done, but also opening up to things that we have not done so successfully before, such as commercial publishing and children’s books.

NAWAID ANJUM: Do you think of genres while getting authors on board?

CHARLIE REDMAYNE: Absolutely. We are always looking for areas of growth and opportunity. In previous years, in our trade publishing business, we didn’t focus on commercial non-fiction. That doesn’t mean that we are not going to focus on the great literary publishing and serious non-fiction publishing. We want to do more of that than ever. But we also want to do the commercial thing. The other thing I’d love to do in India is to grow our children’s business because our biggest such authors are international authors. People like David Walliams are the ones who are selling here. I’d love to grow some home-grown Indian children’s publishing. I think that’s a very exciting opportunity.

NAWAID ANJUM: How do you view consolidation? For instance, two publishing houses — Penguin and Random House — are one publishing unit now. Meanwhile, Amazon in India has tied up with Westland to announce their publishing programme. And Amazon has been re-writing the rules of the game globally.

CHARLIE REDMAYNE: Amazon is hugely important customer for our business. But they are also a great threat because they are not only retailers, but a publisher too. They have a self-publishing programme. Here, in India, for the first time, they actually bought a publishing business. So, they are competing directly with us. The consolidation that you see with Penguin and Random House, with HarperCollins and Harlequin, you will see more such consolidations in the future. It is for so many reasons. One of the reasons is that when you are dealing with a big organisation like Amazon or Google or Apple, then size matters. We are able to negotiate the best possible deals with those organisations so that we, in turn, can pay our authors the best possible return. It’s increasingly important. So, scale and size matters in those negotiations.

Some of the challenges of the digital publishing age are about investing in new skills. The centre of the publishing business is still working together with greater authors. But now market is becoming more and more important and entails data analytics. In London, I employ at least 10 PhD-level mathematicians and physicists who analyse data which helps us price effectively, acquire effectively, and do print runs. All these things give us an advantage. For small publishers, buying those skill sets is going to be increasingly difficult.

NAWAID ANJUM: Are publishers willing to look beyond ebooks and audio books and do more innovations globally?

CHARLIE REDMAYNE: I think there has been a lot of experimentation, but not with a great deal of success. The ebook business in India is a fledgling business. It’s about 1 per cent of our sales, but in United Kingdom it’s 20 per cent. In America, it’s higher than that. If you look at certain genres, our fiction publishing for instance, it’s about 30 per cent. So, they are very, very significant businesses. The ebook business has grown in the UK and it’d grow in India. The audio book business is growing very quickly in America and in the UK and again in India, it’d grow. Beyond that, there has been a lot of experimentation around websites, around apps. Hachette has recently bought a games company. The best way is to just concentrate as a publisher on the things we do well — telling stories and working with authors — and then work with partners to create experiences beyond that. When I was working with J K Rowling, with Pottermore, we worked with Sony to create the book of spells on PlayStation. When I came to HarperCollins, we worked with Samsung to create a product that’s available on Samsung devices around George R R Martin. These things were successful. But now the publishers are becoming developers and game-makers. It’s already very difficult first to make money with books — and we really know how to make books. We should be involved in telling stories on other platforms. But we need to do that in a way that we work with partners. So, at HarperCollins, we run our own ebook and audio businesses. But we are working with partners in the games space, we are working with producers in the television space, and if we have involvement in those areas, we will work with the experts.

NAWAID ANJUM: What are the key differences between the two approaches — traditional publishing and digital publishing? How does e-rights management work?

CHARLIE REDMAYNE: One of the things publishers have been guilty of historically is buying rights and then sitting on it. We shouldn’t do that. J K Rowling, for instance, was very clever. She retained digital rights because when they said they wanted to buy digital rights, she said, ‘What are you going to do with them?’ That was in 1997. I think that if you buy rights then you should exploit rights. We don’t buy any books now unless we have e-rights and audio rights. But then, again, my commitment to authors in the UK is that we will make an e-book and an audio book available the same day that we publish a physical book. That’s with every book we do. Then, beyond that, it tends to be more opportunistic. If we have an idea for a book, then we’ll go to the author and say, look, here’s an opportunity. We need to work with Samsung or Sony to execute it. But if it’s a good idea, and the author is excited by, we’ll find a way of doing it. For me, that’s more the way to do it. We shouldn’t just acquire rights, then expect authors to just rely on us to sit on them if we don’t have good ideas about how to exploit them. We should think about the exploitation of rights, then we should go to the authors and we should be ahead of the curve on it.

NAWAID ANJUM: In 2013, when you joined the UK office, taking over Victoria Barnsley, it was more of a homecoming to you. But publishing insiders read something else into it. An insider told The Guardian: “Bad week for women and a good one for geeks.” It was the week that also saw Gail Rebuck, chairman and chief executive Random House UK since 1991, stepping down from its day-to-day operations.

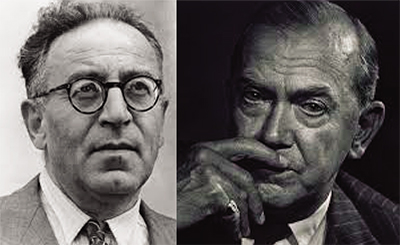

CHARLIE REDMAYNE: The Evening Standard had a headline called, “Publishing has gone mad,” with a picture of Victoria and a picture of me. It now hangs in my loo. Vicky Barnsley hired me. And I have great respect for Vicky. She was a terrific CEO of HarperCollins for 13 years. She was a great publisher and she was a great book person. I came in and I think some of the concerns had to do with the fact that I didn’t come from a publishing background. I had worked for four years at HarperCollins. I worked for two years with J K Rowling. But I was the digital guy and I think people thought that this would be a step away from traditional book publishing into something different. It hasn’t been at all. To be CEO, you need to understand how you can add value. I’m not Vicky. I can’t read a book and say, “This is a voice that needs to be published or a voice that’s going to find an audience.” I don’t have those skills. So, what I do is that I surround myself with brilliant publishers and the editors who have those skills and I add value in the areas that I think I can add value. And those are around broader business strategy, marketing, the commercial, digital and strategic sides of the business, those are the things that I concentrate on and try and add value.

I hope things have settled down. We have retained all of our best people in the UK. We had three years of record profit. And I’m very, very proud. And I think it’s a very happy place to work now. People enjoy themselves and we had some great opportunities. In India, we have gone through a period of change. P M Sukumar (former CEO) left a year and a half ago. V K Karthika (publisher) left recently. We also lost Krishna (Krishna Naroor, Collins Learning India MD, was replaced by Chaitali Moitra in May 2016) who was running our education business. I brought in Ananth Padmanabhan to run the business. The reason I did that was I wanted to refocus the business into a broader publishing business. Literary fiction, serious non-fiction is as important as it has ever been. But I also wanted to open up the doors to big commercial opportunities that I saw here in India and I thought that Ananth was the right man to do that. I was very sorry that Krishna left. He had done a terrific job since Collins Learning started. He remains a friend of the company. Chaitali has come in. She has great experience from her time at Macmillan. She has been doing a tremendous job. And we see that business really really grow. When Karthika left, I was very, very sad to see that because she is a friend and she is a friend of the company. But it gave us an opportunity to refocus. Her role as a publisher-at-large meant that to a degree the focus was on the areas of publishing that she really looked at. So, now, we have got publishers in all the different areas — we have got a publisher for serious non-fiction, publisher for literary, commercial and children. So, now the structure of our trade business in India is very similar to our UK and American businesses where we have experts in their areas as heads of each division. I was very sad to see those people leave and we wish them well. There is not going to be any chief editor anymore. All publishers tend to have a focus on their area that they love the most. What I have is a bunch of great executive publishers who excel in their areas and I give them the freedom. And that’s important to me. That’s what we will do in India.

NAWAID ANJUM: How do you balance between the literary merit of a book and its marketability? What is more important?

CHARLIE REDMAYNE: With Fourth Estate, which is very literary in its span, it was the big question. When it started, Fourth Estate was seen very much as an area of the company that didn’t make money. But it was there to say something about HarperCollins as a business: we published Doris Lessing, Hillary Mantel and all these great writers. My view in this respect is that there’s no reason why you can’t publish great literary fiction and do so profitably and there are plenty of companies that do that. That was the challenge I gave to Roth-Ey (David Roth-Ey is the executive publisher, 4th Estate & William Collins, responsible for all the content and output of these prestigious literary imprints). He’s been very successful. The business is now profitable and we are still publishing the great literary stories that should be told that may not make money in the short term, but often makes money in the long term. Remember, the value of the publishing business is in its backlist. In commercial publishing, the focus is more on the frontlist, but the backlist is gone. In the literary segment, it’s the backlist that’s relevant for 30 years. We need a breadth of publishing. We are certainly looking to grow all areas of our business in India and the UK. I think we can publish literary really successfully and commercially successfully. What I’m not interested in doing is publishing books that seem to be important, but no one is going to read them. I don’t understand that concept. Why is a book important if no one is going to read it? A lot of people must read it for it to be important.

NAWAID ANJUM: In India, do you at all look at indigenous, home-grown publishing houses as a competition?

CHARLIE REDMAYNE: Our business is divided into four principal areas — HarperCollins Education business in India (Collins India which was started in 2013) is expanding. We have got the big US titles being sold in India and we’ve got a UK business coming through. And then we have our local publishing. Historically, the big trade titles coming in from the US and UK have been making up the commercial publishing list in India. Local publishing in India is focused on serious non-fiction and literary fiction. We’ve invested a lot of money in some of the best titles in India. We want to be publishing locally across the board. The areas of growth we see have been in the commercial space. We have invested in the new commercial team and the children’s team. I would love to see local Indian titles for children growing... That’s our business. Certainly, we see competition from Penguin Random House India and others who are bringing titles from the US & the UK like us, but also local publishers, who are publishing locally. We want to grow in all areas.

NAWAID ANJUM: In terms of overall trends in publishing in UK and India, what are the differences and the similarities?

CHARLIE REDMAYNE: I think the type of books that are read here in India is different. In terms of the impact that digital has had, India is way behind and that’s great as it gives us an opportunity to watch the trend in the UK and study the market here. I think digital growth will be different in India. In the UK and US, it was very much device-oriented. People bought Kindle and reading devices. There were great surges during Christmas when people gifted Kindle. In India, it’ll be device-led as the device is already in people’s hands. If you go to work in London as I do, you’ll see people reading on their smartphones that’s where digital reading takes place in India. Amazon is a big company and they make every book available. They advertise hugely and they will build and grow their brand and the challenges that the Indian publishers face is the same challenges that we faced some years ago and we need to wake up to it. I think one of the biggest challenges from Amazon is their self-publishing programme. And, in India, they are in publishing business. What we have seen is Amazon very much favouring its own authors in terms of promotion.

NAWAID ANJUM:: How do you view the self-publishing platforms?

CHARLIE REDMAYNE: There are some really good books on self-publishing platforms, but there are also some terrible ones. The way Amazon promotes books means that a lot of consumers are having very bad experiences of buying books by recommendations that are really poor. If you had spoken to me about 10 years ago and asked about our brand, I would have said our authors are our brand. We’d focus on advertising them more than HarperCollins. When people are going to buy books, they are going to look who the publisher is. They’ll look at the titles, the subject, the author and the publisher. If they recognise the publisher, they are going to feel that they are trusted. I do hope that when people pick up a book, they are reassured when they see that it’s a HarperCollins book. HarperCollins is a mark of quality and that’s going to be increasingly important where there are hundreds and thousands of self- published authors being given equal promotion by these digital platforms.

NAWAID ANJUM: Among the big guns, who do you see as your major competitors in the UK?

CHARLIE REDMAYNE: Penguin Random House and Hachette. Both their books have done terrifically well in the last two years in terms of their top line sales. There are some very talented smaller publishers too. Macmillan published a book by Joe Wicks, a healthy eating guru, who is selling millions and millions of books. When you get hits like that, it feels really great. I must admit that the thing that disappoints me with HarperCollins is that in the last three years, we’ve had some big hits — we had David Walliams who’s one of the biggest authors in the UK in children’s book — but we’ve haven’t had any breakaway hit. All the hits we had, we knew: we knew about David Walliams and Wilbur Smith and other big authors. We know what these big authors do. It’s waiting for that moment where the book just flies and we haven’t had one. But may be next year.

NAWAID ANJUM: Have you signed some major debuts of late?

CHARLIE REDMAYNE: Every year, we have at least 3-4 what we call event debut fiction authors. Last year, we had The Trouble with Goats and Sheep by Joanna Cannon. Last year, it sold some 20K hardbacks. We launched the paperback in January. We had an extraordinary book last year called Behind Closed Doors by B. A. Paris. We launched in digital and sold hundred thousand copies. When we saw this happening, we sold almost as many copies in physical. That was a real case of digital marketing pulling it through. We made it available at a very low price. And we ended up on Kindle top 5. We did a lot of social media promotions. This year, we have some huge books that we hope will work. They are big debut authors.

NAWAID ANJUM: Tell us something about your reading habits.

CHARLIE REDMAYNE: I love books. I’ve always been a reader. I’m a fan of books. I’m not an editor. I don’t come from that background. I don’t have the editorial instincts that I can read a manuscript and go, ‘This is something we need to publish.’ I surround myself with brilliant people. Publishing industry is an incredibly nice place to work. I have worked in television, marketing, advertising and the Internet and the nicest people that I have worked with are in publishing. Authors are nice people. And they are storytellers. So, they are interesting people. The thing about authors is that even if they are not very nice, they are pretty interesting. In terms of books I love, I read commercial fiction. So, I have read every single book that Bernard Cornwell has written. I love a lot of psychological thriller and historical fiction. I love Karin Slaughter. So, I was delighted when we signed her. My favourite books are The Pillars of the Earth by Ken Follett and the follow-up, World Without End. I read The Pillars of the Earth because my little brother, Eddie Redmayne, who was starring in an adaptation of The Pillars of The Earth, said it was extraordinary.

I didn’t go to university. So, my ambition in life, if I ever earn enough money to stop, which is highly unlikely, is to do a history degree (laughs). The idea of doing nothing, but reading something that I’m interested in for three years would be great. At HarperCollins, I spend a lot of time reading. We publish hundreds of books every year and I try and read a bit of each of them so that when I meet the author, talk to the author, I can get a feel of what they do and I think that’s important.

NAWAID ANJUM: How different was Pottermore? There were a lot of things you got done there.

CHARLIE REDMAYNE: I loved my job as the chief digital officer. But the reason I left HarperCollins in the first place was that I was in America while my wife and kids were in London. I lived away from my family for two years and it didn’t work. So, I left with a very heavy heart and I went to Pottermore. It was great to work with a brand like Harry Potter. We built some great products. We got the retail business up. We sold a million pound worth of ebooks in the first two days of its launch. We did things like Book of Spells and Book of Potions with PlayStation. Book of Spells sold 1.8 million units in the first month. We got a lot done and would have changed the model of it. But when the opportunity came to come back to HarperCollins and to run the UK business, it meant that I could work with the company I wanted to work for and in the country I wanted to work in. When I went to work with Pottermore in the first place, I told Neil Blair (Rowling’s longtime agent and Chairman of Pottermore), whom I was reporting to, that I’ll do this for two years because I’m the perfect person to set this up, but I’m not the right guy to run this. My background had been doing digital start-ups. I knew how to do digital start-ups and we did this very successfully. The team that took over had a different view on some of the stuff that happened and Pottermore has gone in another direction. Those were really exciting two years. Getting the opportunity to spend some time with JK Rowling was really special as she is an extraordinary woman, not just as a creative person, but also as an individual. My brother, Eddie, has acted in Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them, directed by David Yates. The thing I most admire about her is the propensity to do good in this world, giving money to causes that she is passionate about. A lot of people talk the talk. But she walks the talk.

Eddie Redmayne in a still from The Theory of Everything.

NAWAID ANJUM: Tell us something about Eddie. We have loved his scintillating performance in films like The Theory of Everything.

CHARLIE REDMAYNE: He is 15 years younger than me. By the time he was growing up, I was an adult. He was always fascinated by theatre and film. He started acting when he was 11. I’d often have to go and pick him from The London Palladium. The other three brothers are deeply untalented. We are much more about sport, which is our thing. Eddy has always been incredibly talented. He’s an incredibly nice and hard-working guy. I’m not involved in his professional world, but the directors like to work with him which makes me very, very proud of him. I always thought that he’s going to be a very good actor, but he has far exceeded anything you expect from someone who is in your family but ….people don’t believe we are brothers, because we look different. We are half-brothers. I look like my mother and he looks like his mother. When he won the Oscar, I was in Toronto. Two weeks later, I was flying back for a business meeting and I handed my ticket over to the lady at the counter. She looked at it and asked, “Any relation to Eddy?” I said, “Yes. He’s my brother.” And she said, “Yeah, right,” and gave me the ticket right back.

I love cricket. I wanted to play professionally. I was a soldier in the Army in Combined Services, but unfortunately my career was cut short by tragic lack of talent and so that was that. I was trying to be a big hostile fast bowler and I was big enough and hostile enough, but I quit playing when I left the Army at the age of 22. I carry on playing cricket since I love it. On weekends, I play with my son Jack, 15, who is in school.

NAWAID ANJUM: What else do you like doing?

CHARLIE REDMAYNE: One of my great escapes is reading. I read for fun. I have to read bits of hundreds of books every year. So, every holiday, I carry books and read them cover to cover. I love to play cricket. I love to play golf. In London, I have a house in the country. We have friends stay over on weekends for dinners and drinks. I love travelling. I travel around a lot for my job.

NAWAID ANJUM: Where do you see HarperCollins headed?

CHARLIE REDMAYNE: I see it growing organically and possibly through acquisitions too. I would like us to get better at predicting a lot of trends. We’ve been spending a lot of time trying to get what the next trend would be. In UK business, we have a lot of colouring books and then we have Ladybird children’s books. I want to be predicting those things better. I think that the areas I would like to see us involved is storytelling across all platforms — physical books, ebooks, audio books et al which will continue to grow. How do we get involved in games manufacturing, television? Telling stories across every platform becomes an increasingly important part of what we do. So, ultimately I want to grow and the real growth will come through the traditional — educational, reference and trade — publishing businesses. They are becoming bigger and bigger. We are investing in things that we need to do — buying big books we want to win, spending money on data analytics that’s really a huge benefit to us, how we sell ebooks, acquisitions and print decisions. It’s about becoming a more digitally driven business, but that’s just one end. It’s about how we use digital resources that we have to inform business consumer insight. When I first joined HarperCollins as a digital director in 2008, I took a presentation and I wanted everyone to like me. So, I said things that you couldn’t argue with really. One of the things I said was that we should put consumer insights at the heart of everything that we do. A senior editor said, “Charlie darling, I don’t think you really understand publishing. It’s not about consumer insight. It’s about editorial instinct.” I didn’t approve of her. I subsequently discovered that she was right. It is about editorial instinct. It is about these great editors who have the instinct. But what we are trying to do in UK is use consumer insight to help form an editorial instinct. May be that editorial instinct will get better. So, it’s not just one thing. It’s both combined.

NAWAID ANJUM: How do you approach your role and responsibilities as a CEO?

CHARLIE REDMAYNE: You have to be clear about what you are good at and you have to be very honest about what you are not good at. And then you have to surround yourself with people who are really, really good in all things that you are bad at. That’s what I did. I’m not an editor. I’m not someone who comes from a background steeped in publishing. So, I surround myself with people who are and I’m proud of them for doing things that they think are right. And I support them in doing it. I hardly go against my publishers’ views on a book. I may argue about the price or the market it may reach or whether it’s competing with another book, but ultimately, I would never argue about a book getting published. The last three years have been record years for HarperCollins UK in terms of profits.

.jpg)

INSIDE.jpg)