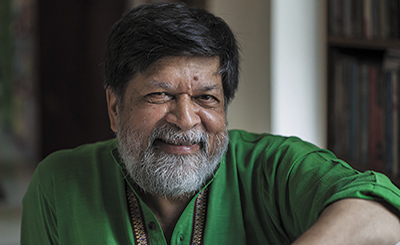

Shubigi Rao, curator for the Kochi-Muziris Biennale 2020. Photo: Kathrin Leisch

The curator for the fifth edition of Kochi-Muziris Biennale, scheduled to kick off on December 12, on the challenges of curation during the pandemic, the inevitability of physical isolation informing the artists’ work, their rethinking of how they produce art, the biennale as a space of comfort and consolation — a counterpoint to isolation and pain — and unearthing the marginalised and subsumed histories and narratives in her work

Shubigi Rao is the curator for the Kochi-Muziris Biennale (KMB) 2020. Her interests include libraries, archival systems, histories and lies, literature and violence, ecologies, and natural history. Her paperworks, texts, films, and photographs look at current and historical flashpoints as perspectival shifts to examining contemporary crises of displacement, whether of people, languages, cultures, or knowledge bodies.

Her current decade-long film, book, and art project, Pulp: A Short Biography of the Banished Book, is about the history of book destruction and the future of knowledge. The first Pulp volume was shortlisted for the Singapore Literature Prize (creative non-fiction), 2018. The first portion of the project, Written in the Margins, won the APB Signature Prize 2018Juror’s Choice Award. Rao has also been featured in March Meets 2019, 4th Kochi-Muziris Biennale (2018), 10th Taipei Biennial, (2016); 3rd Pune Biennale (2017), Digital Arts Festival, Copenhagen, Denmark (2013); and 2nd Singapore Biennale (2008).

In this interview, Rao, 45, says, “The KMB, as a people’s biennale, is firmly rooted in its locale. And this regionality is crucial. As I see it, the KMB can be a crossing for global conversations and exchanges, without losing the richness and depth of original contexts”. Excerpts from the interview:

Ina Puri: There is a lot of interest in your curatorial concept and what you have planned for the forthcoming edition of KMB — your idea, for instance, to “celebrate our ability to flourish artistically in dire situations”, keeping with the spirit of the times. After Anita Dube’s strong bid to be more inclusive and chart out a course that was very different from the earlier curator, Sudarshan Shetty’s exploration of practices beyond the art world to bring in the performative element, it is your turn and it must be quite a challenge?

Shubigi Rao: The biggest challenge is, of course, the current global pandemic, but there are always challenges to exhibition-making, especially one on the scale of KMB. And yet it is a creative act to think through problems, to circumvent obstacles, and to work with people to collectively, inventively dismantle challenges. At the very outset, I was determined to think of the Biennale as a crucible, capable of holding the diverse discourse of the critical, political, and social in artistic practices.As an artist, I’m driven by many things — the need to situate myself in this world (historically and in my current reality), my responsibilities to not just our species but to the planet, and to recognise that artistic and literary practices have the potential to strengthen existing communities and to generate new thought and action. These imperatives continue to be present in my curatorial work for the next KMB, and this work will, in turn, inform my praxis. Quite a few artists manage and perform multiple forms of artistic labour and production, and are often continuously reflecting and rethinking. I have to say that I see challenges as creative opportunities, and a chance for people to work collectively with common cause.

Ina Puri: How are you communicating with your participants without being able to visit their studios?

Shubigi Rao: I was fortunate in being able to complete the bulk of my curatorial travel and research before the lockdowns came into effect. Looking back over my research and travel since June 2019, I find tremendous diversity in regionally specific works, but also a sense of familiarity. In speaking with overlooked artists and collectives, my conviction remains that the Kochi-Muziris Biennale is well-suited to hold these practices, ideas, and conversations from the majority world. My time in Latin America, in Sápmi (the Sami lands in Northern Europe), Southeast and East Asia and in Africa has enrichened my curatorial work for KMB 2020. Over the last two months, my team and I have been in constant touch with the artists through calls and online meets, figuring out solutions to halted production and lack of access to sites. In some ways, this has been an opportunity for a number of the artists to rethink their approaches, methods, and the reliance on conventional resource-intensive processes.

Ina Puri: Earlier, we saw curators actively travelling to other biennales and major art exhibitions. Do you feel at a disadvantage that you have not had the same opportunities?

Shubigi Rao: On the contrary, I was able to travel extensively for my KMB curatorial research, and this included being hosted in a number of visiting curator programmes in biennales and art fairs. I ended my travel in Sydney, for the Biennale, in March. I have anyway been travelling widely for the last eight years for my work, and as a participant in seminars, exhibitions, etc. So, the KMB travel was an extension, in a way, of a process to which I am accustomed.

Ina Puri: Have you had a chance to explore the nooks and corners of Kochi? When was the first time you visited the city?

Shubigi Rao: I stayed there for almost two months in 2018 to make my work for the last edition. It was exhilarating to be based in Kochi and construct the work in-situ from the ground up. I rarely get the opportunity to work in the field, so to speak, from start to finish. For almost two months while I was based there, I immersed myself in the libraries and archives of Kochi, and with its people, who very generously gave me access to their stories, and to places from boatyard workshops, junkyards, and pulping stations, to private book collections. All this was facilitated by the dedicated and incredibly hardworking team behind the Kochi-Muziris Biennale. I formed close friendships with them as we worked on my film and installation from inception to end. One of my favourite people is TA Salan, who works in a junkyard in Mattancherry. He is a natural actor and storyteller, and one of the most generous people with whom I’ve worked. He also gave me a copy of Homer’s Odyssey that had been damaged by the flood last August, and passages from this copy found their way into my film as well.

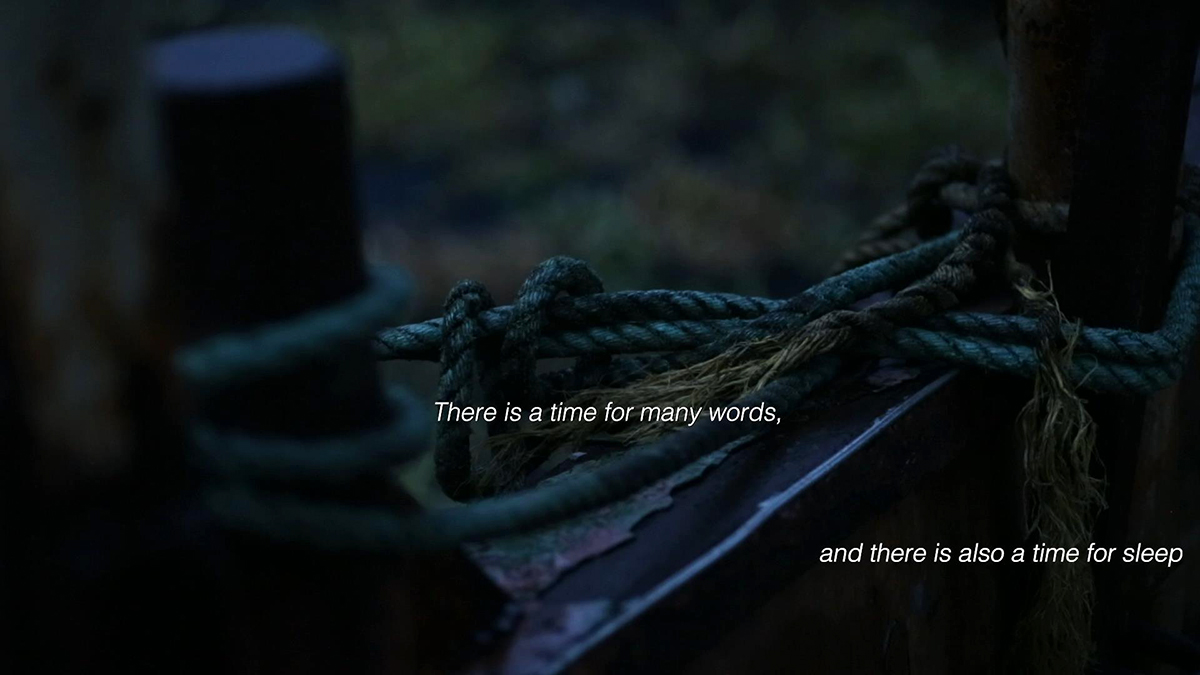

Library books damaged by floods in Kerala, August 2018. Giclée print from The Pelagic Tracts by Shubigi Rao, commissioned for the Kochi-Muziris Biennale 2018. Image courtesy of the artist

Library books damaged by floods in Kerala, August 2018. Film still from The Pelagic Tracts by Shubigi Rao, single channel film commissioned for the Kochi-Muziris Biennale 2018. Image courtesy of the artist

Ina Puri: The historical context is something that has been an area of research for your own art practice. Will you be seeking to emphasise the historical angle in your curatorial programme?

Shubigi Rao: Histories are embedded in every work, even if not readily evident. The challenge for me (earlier, as an artist, and now as curator), is to unearth (or support those who unearth) marginalised and subsumed histories and narratives, and follow their threads through contemporary practice and discourse. I don’t see histories as separate, we do not live, make, and think sequestered from the past, and it would be strange to imagine that art, literature and so on have no dialogue with histories. Speculative fiction, for instance, draws upon historical events, ideologies, interactions and movements in its imaginings. I find history to be a living, mutating thing, a hydra, with myth and factual rendering all mixed up, with murky agendas and buttressed structures and ideologies. History is also more than rise and fall of empire. For me, it is also the migration of language, of culture, of mathematical concepts, and even of disease. This polyvocality is present when I think, make, or write as I have no singular voice, and this is also the reason why I gleefully immerse myself in disparate fields of knowledge. A side-effect of this is my impatience with gatekeeping, or rigid categorisation — because, in reality, most knowledge structures are unwieldy, unbalanced, and very porous.

Ina Puri: This ‘polyvocality’, of course, has been vital to you as an artist straddling several worlds. Besides history, you also seem to dwell on a wide range of other disparate fields — from archaeology to libraries and archival systems, from neuroscience to literature to ecology, from censorship to violence and acts of cultural genocide. Do you see this reflecting in your curatorial choices? Would you, for instance, be consciously seeking out artists with similar methodologies?

Shubigi Rao: Not necessarily, as I prefer an indiscriminate approach as a curator. I have other points of entry when examining practice. Of importance to me as the curator here, are concerns like the artistic fidelity of the project to the stated intentions of the artist, their position, their methods of inquiry, ethics and sensitivity to materiality and contexts.

Ina Puri: I am curious if the artworks will reflect loneliness. Will it have led to a frightening desolation and darkness or will it be fertile? What, according to you, will be the relationship between art and isolation?

Shubigi Rao: It is inevitable that the physical isolation experienced by a number of artists would inform their work, but more than that, I can see their navigation, their rethinking of how they produce, being more evident in their work. Loneliness as a pervasive condition existed before the pandemic, and I hope that the experience of lockdown might dispel some of the complacency and apathy towards those who have already been experiencing isolation, loneliness, and neglect. People respond very differently to the lockdown, but I believe the capitalist pressure to constantly be productive, (even in a time of isolation, fear, uncertainty and pain), is an unnatural weight, and one that we should question.

Film still from The Pelagic Tracts by Shubigi Rao, single channel film commissioned for the Kochi-Muziris Biennale 2018. Image courtesy of the artist

Film still from Written in the Margins by Shubigi Rao. Single channel film comprising, 2018. Image courtesy of the artist

Ina Puri: I imagine for the art practitioner, too, isolation is going to be apart of the narrative. Like Sherry Turkle writes in Alone Together (2011): “Likewise, at a screen, you feel protected and less burdened by expectation. And, although you are alone, the potential for almost instantaneous contact gives an encouraging feeling of already being together.” This is unprecedented, the process artists are experiencing for the first time. I wonder how it will reflect in their work for KMB.

Shubigi Rao: This edition of KMB will be very much a reflection of our current realities. I have already seen the changes in the work of a number of artists, as I have mentioned above. Some have had to completely change their proposed work. This is not necessarily a problem — because this is part of the rethinking that I believe we must do.

Ina Puri: About the Venice Biennale, Swiss art historian Beat Wyss writes: “Under postcolonial and post-national conditions, the national pavilions appear as market stalls of aesthetic assertion. The Venice bazaar conduits its cultural exchange in a market where, using discourse commodity of art as a negotiable object, entirely different regional perspectives come together in a global process of haggling over tolerance and human rights — the ‘small print’ of the Enlightenment.” What is the role of the biennale in the present times?

Shubigi Rao: Given the number of biennales worldwide, it would be unproductive to generalise a singular model, or ascribe singular contexts and relevance to them. Also, the Kochi-Muziris Biennale is unique for two distinct reasons — firstly, it is an artist-led endeavour, and is, therefore, more liberated from certain entrenched curatorial methods. It allows for inclusive forms, discussions, and practices with a sensitivity that is sometimes absent in the replication of conventional exhibition formats. So, while the biennale as format is still important, it becomes vital too to recognise that the global south has its own established networks of thought, practice, and discourse. The KMB is also a vital platform for emerging practices and voices in South Asia. This is very exciting to me. As an artist-led biennale the KMB demonstrates a wide spectrum of sensibilities that are deservdly very well-received both locally and internationally.

Secondly, as a people’s biennale, it is firmly rooted in its locale, and this regionality is crucial. As I see it, the Kochi-Muziris Biennale can be a crossing for global conversations and exchanges, without losing the richness and depth of original contexts. The culture, history, and ecosystem of Kochi are incredibly robust. Historically, Kochi has withstood and amalgamated the often fraught legacies of numerous rulers, ideologies, and multiple European colonisers. I couldn’t imagine a more apt setting within which to stage an international people’s biennale.

Ina Puri: Last year, since KMB was held in the wake of Kerala floods, there was a great thrust on it as a healing and regenerative space. Do you envision the same for this edition — making it as a place for healing and hope and showcasing what propose art can serve during a crisis like this?

Shubigi Rao: I’m reluctant to ascribe such redemptive power to art, but I maintain that there is an inherent vitality involved in the making and thinking in artistic process. In times of disaster, art may alleviate, bring some measure of solace, but eventually the very real labour of rebuilding community, livelihoods, etc., must happen. It is also reductive to consider art in utilitarian terms. I do hope the biennale can function as a space of comfort, consolation, and perhaps as a reminder of what is shared, a counterpoint to isolation and pain.

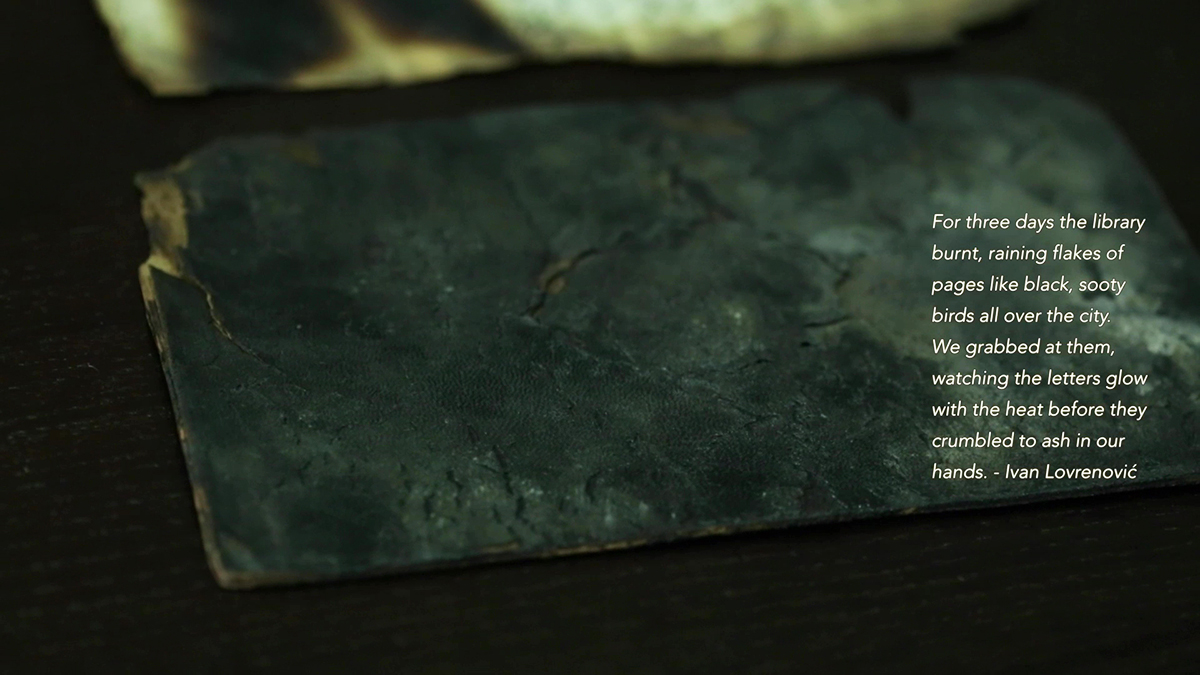

Ottoman manuscript sealed shut by the flames from the burning of the Oriental Institute, Sarajevo, Bosnia-Herzegovina. Film still from The Wood for the Trees by Shubigi Rao, 2018. Image courtesy of the artist

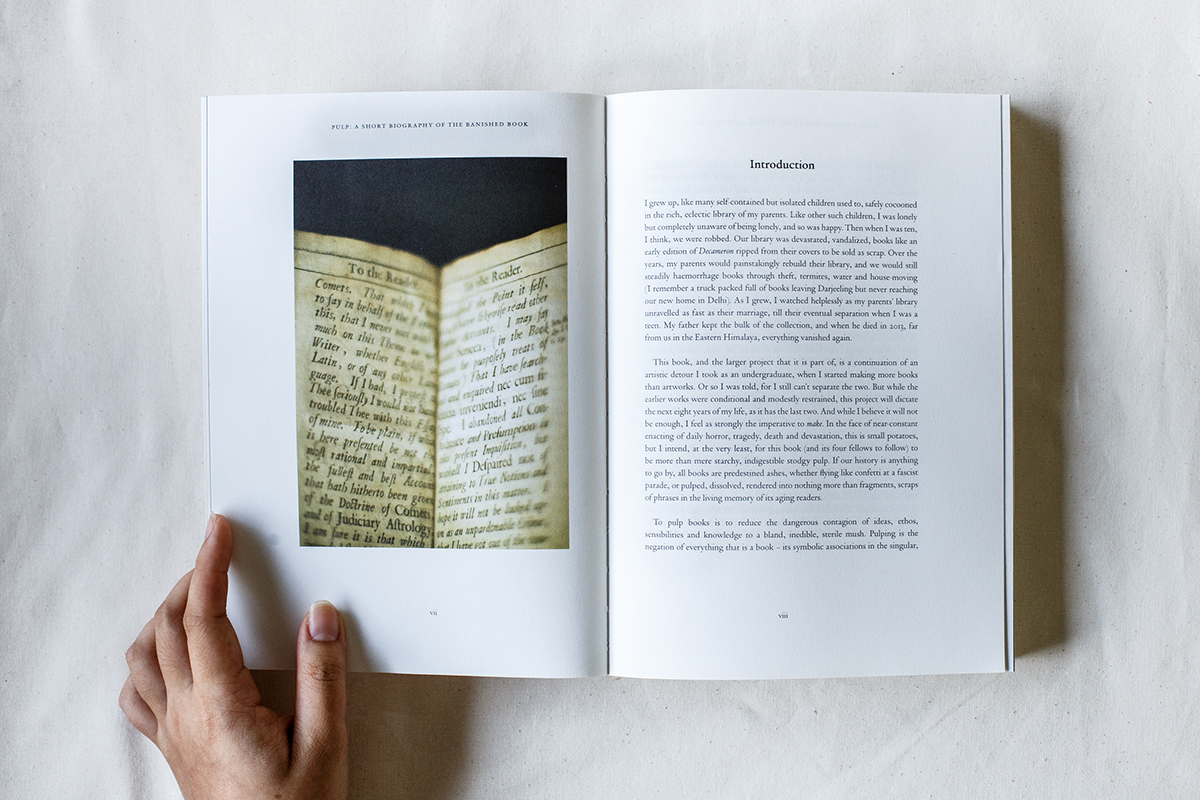

Inside pages from Pulp: A Short Biography of the Banished Book: Vol. I, by Shubigi Rao, published by RockPaperFire Singapore: 2016. Photo: Maria Clare Khoo, image courtesy of the artist

Ina Puri: Last year’s edition also saw a great deal of emphasis on hyperconnectivity, its misuse by the powers-that-be and the freedom afforded by the internet. In these times when most of us have been staying in, technology has helped build solidarities more than ever before. Will this year’s edition reinforce the role of internet and technology?

Shubigi Rao: Technology is already embedded in our lives, so I don’t see it as separate. A number of artists do foreground the issues of surveillance, technological intrusion and co-opting, the implicit biases of AI, as well as the dissonance between need and consumption in tech innovation. Our commingled digital futures are inextricable from the transmission of knowledge, ideas, and capital, and so too are we subject to neoliberal infiltration and control. Though we may share the same concerns of land, migration, the climate crisis, rising neo-fascist, totalitarian and theocratic regimes, embedded technology and surveillance, for instance, we diverge in our methods and approaches in thinking and in making. What is interesting in an exhibition on the scale of a biennale is retaining the complexity of this discourse.

Ina Puri: Talking of technology, AI developed in Vienna is set to debut in the art business and will curate the Bucharest Biennale. Art practitioners around the world have long been under the impression that they will remain unaffected by the depredations of artificial intelligence since machines can be no substitute for human creativity. Do you think it’s perhaps time for a rethink?

Shubigi Rao: The case of Jarvis, mentioned by you here, is a fascinating example of possibility. I also think it will demonstrate the problems of AI, and will say more about the implicit biases of AI. From the unconscious preferences of its programmers or makers, to the restriction of artist selection to existing rosters of museums, universities, and galleries, this is not a particularly progressive move. Consider the push towards decolonising the museum and the canon. Consider also the gender and racial imbalances inherent in museum and gallery selections, and you can see how Jarvis has been hobbled by historical hubris, state cultural capital, and commercial interest. This is not to say it will not be an interesting selection. On the contrary, I think is an excellent exercise that may serve to further the discussion about AI of course, but also about the nature of inclusion and validation.

Ina Puri: Since you have participated as an artist, Kochi is bound to welcome you with their traditional warmth in your new role. What plans do you have regarding your own visit and setting up? Good luck, Shubigi! You don’t have it easy!

Shubigi Rao: It may not be easy, but it has definitely been immensely meaningful — I have had unforgettable conversations, encounters, and interactions with incredible people and practices, and been privy to the thinking and actions of artists, curators, writers, and cultural practitioners from across the world. It is an immense responsibility, but also an excellent opportunity to bring some of this to Kochi, to be present alongside the rich discourse and practices of South Asia.

This interview, on our June 2020 cover, is part of our special issue on Art in the time of Pandemic, curated by critic, author and one of our contributing editors, Ina Puri

More from Arts

Comments

*Comments will be moderated