Dutch photographer Martin Roemers. Photos courtesy of Roemers

For Dutch photographer Martin Roemers, 54, it’s the streams of human energy that make any city what it is. It’s the crowd which is his “element”. Roemers’ latest series of works, Metropolis, draws on the fact that more than half of the world’s population lives in cities today.

In all, world’s 28 cities meet the UN’s definition of a “megacity”: one with more than 10 million inhabitants. Tokyo, home to 38 million people, tops the list of megacities. The next biggest are Delhi (25 million), Shanghai (23 million) and Mumbai (21 million). Intrigued by this process of urbanisation, Roemers travelled to 22 megacities across five continents to photograph life there, between 2007 and 2015.

Shot from high vantage points on medium format film camera in cities like Mumbai, Kolkata, Dhaka, Karachi, Manila, Beijing, Guangzhou Lagos, London, Moscow, Sao Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, Los Angeles, New York, etc, each of these photographs is soaked in the variegated feel and flavour integral to these mega cities, heaving with the multitude of its inhabitants, often depicted in colourful blurred trails. These photographs capture the distinct, specific character of each of these cities and also highlight the similarities — movement of people in the backdrop of modern roads, subway stations, railways, buildings and shopping complexes.

An exhibition of Roemers’ award-winning series, Metropolis, opened at the India Habitat Centre (IHC) in New Delhi on February 16. Jointly organised by the embassy of the Netherlands, Nazar Foundation and the IHC, the exhibition is on till March 8.

Roemers lives and works in Delft, the Netherlands. Having studied photography at the AKI Academy of Fine Arts in Enschede, his work has been exhibited in Europe, the US, Asia and Australia. Roemers has twice won a World Press Photo Award, in 2006 and 2011, for Metropolis. In 2015, he was given the LensCulture Street Photography Award for Metropolis.

The 85 photographs in the series have also been published in the book: Metropolis, published by Hatje Cantz. It includes texts by Ricky Burdett, Azu Nwagbogu and Els Barents.

Roemers’ earlier photo projects have engaged with the consequences of the Cold War and the life of soldiers in Kabul in such series as Kabul (2003), The Never-Ending War (2005), Relics of the Cold War (2009) and The Eyes of War (2012). His solo show is also travelling to New York next. Excerpts from an interview:

THE PUNCH: Tell us something about Metropolis, perhaps your most ambitious project so far. It’s a very relevant and timely series. Urbanisation and the growth of different cities around the world make for a fascinating study. The photographs in the series are portraits of mega cities around the world as much as they are portraits of the universal human condition.

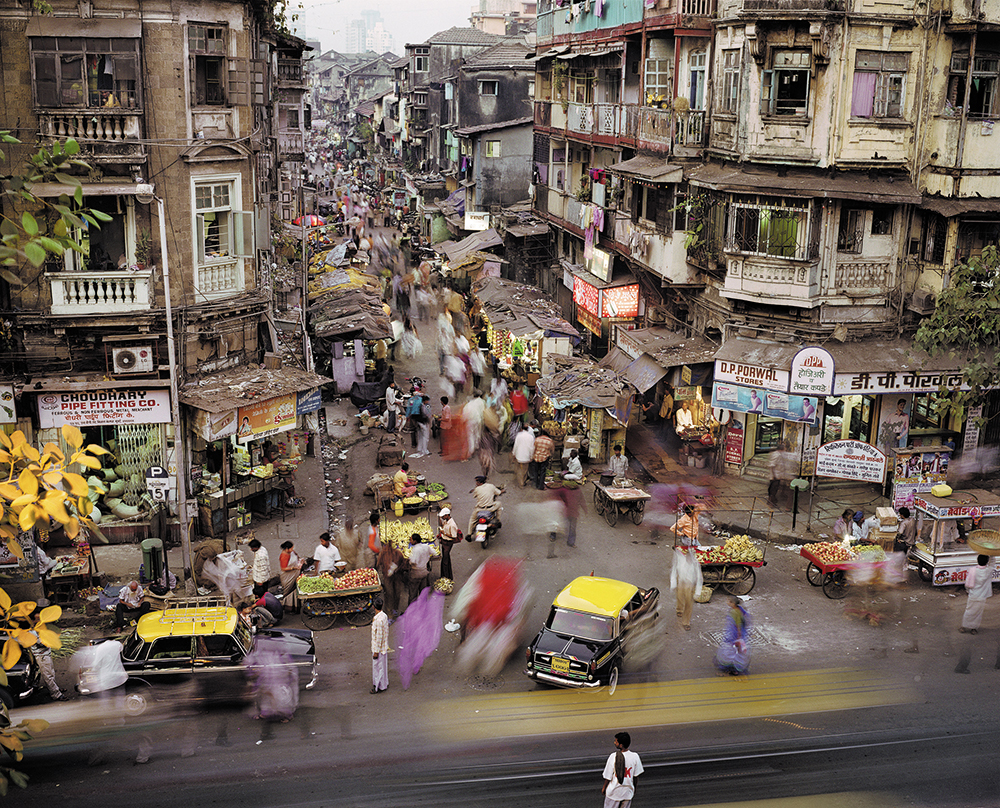

MARTIN ROEMERS: It developed in stages. The trigger to do this project was India. I visit India quite often. For a long time, I was in Mumbai. I was always fascinated by the city life in Mumbai. It’s so busy and crowded. It’s a little chaos. It’s the smell. It’s the noise. There is so much energy in Mumbai. Actually, I was wondering how you can visualise the character of such a vast city in only one image. That started me thinking how to encapsulate this energy. I want to show the city — as in buildings, infrastructure, traffic — but also people on the streets. A city like Bombay is about movement. It’s about speed and living in the fast lane. I knew I had to do something with speed and movement. I developed a concept: a panoramic image from a high point, looking over streets and buildings etc, but not too far away because then you get detached from what’s happening on the street. People should be visible and I should be able to identify them. So, I worked with a long exposure time to visualise the speed and the energy, but at the same time, I was very much focused on individuals who populate the streets. I experimented with this concept and shot on film. When I got home, I developed everything and the result was quite amazing. You see these blurs from moving traffic, you see people sitting still like on an island in the sea because everything around them is moving. That was actually the first tryout. I perfected this concept more and more. I went again to Mumbai and to Kolkata, the only city in the world where you have the hand-pulled rickshaws. I wanted to include this element in a Kolkata photo. I found a location with a lot of rickshaw traffic. The rickshaw had to be captured when it stood still because I expose for 2-4 seconds. I waited for two days to wait for the right moment when every element fell on its right place in the image. I’m looking at streams of traffic, individuals who are interesting for me and I wait until they stand still in my image long enough to have them visible and sharp. That’s what I’m doing the whole day, looking for locations, checking if there is a roof or a balcony or someplace high from where I can shoot at the right time of the day. In Indian cities, where it’s sunny all day, I shoot in the last two hours of the day, then the light is soft enough to make my photo.

Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel Road and SS Maharaj Marg, Kamathipura, Mumbai

I worked for quite some time in India. In 2009 a report was published by the United Nations’ World Population Fund. The report stated that more than half of the world population lived in a city. The UN expected that 75 per cent of the world population would live in a city by 2050. That was breaking news. This was a good reason to expand the project, make it about global urbanisation because it had become relevant now. Under urbanisation, cities have to be developed. One has to think about how to build a city and tackle its myriad problems. I wanted to address all these elements. That’s when I started to take it worldwide. The UN has the list of mega cities. When I started, they were 22. Today, there are 29 mega cities. I started to visit every one on this list. Most of the mega cities are in Asia, others in North America, South America, Europe and Africa. Before I went to any of these cities, I had to ensure I knew what could be important for me, decide on what elements I wanted to see and photograph. I always work with a local assistant, somebody who knows the city, knows what I am looking for. Most of the time, this was a young photographer. Before I arrived in the city, we made a list of possible locations. Being there, we drove to those locations to check if they were worthwhile, if there were high points to shoot from. Sometimes, we needed permission to enter a building. I stayed one week in every city. I looked for the differences between mega cities, but also about what they have in common — poverty, displacement, etc. Can cities cope with all these newcomers? Is there enough infrastructure and housing? For example, there are large slum areas in Indian cities like Mumbai. In many such cities, there is no real infrastructure, no electricity, no sewerage system and no water. That creates a lot of problems. In a photo on Mumbai, there is a beach right next to a slum area in Colaba. There you see a lot of men using the beach as a toilet because there is a lack of facilities in the place they are living in. In general, these photos show you what urbanisation is about. I especially like Indian cities because they are so hustling and bustling. I always enjoy being there. They are the cities that triggered this project.

THE PUNCH: In all your frames in the series, a crucial element is the fine balance between the static and dynamic forces and objects. Could you talk about the composition, texture and technique you employ to achieve this?

MARTIN ROEMERS: There should be a balance between static and moving elements. While shooting, I was constantly waiting for things to fall into place. I watched the movement of the traffic; I can anticipate on it because I knew that every two minute there’s a bus or a tram coming and people have to wait before they cross the street. At the moment when all objects fell into their place, I pushed the release button. And that’s why these images are really filled up: you see elements in every corner. When I observe what is happening on the street, I can only follow so much elements — five or six. When I expose, I am never quite sure these elements will be visible on the image because, a lot of things can change in an exposure of 2 or 4 seconds. Most of the time, but not always, I had a pretty good idea whether a specific situation would provide a usable image or not. I could only see the results when I was back home because it’s all shot on medium format film. After developing the films I start selecting the images which capture everything and have a fine balance between static and moving elements. What I want is that the image tells a lot of different stories. You can really see that if you make big prints. If you study them, you see little stories everywhere because it’s also detailed and so sharp. I even discover new elements, new details when I look at these images again even though I have seen them hundreds of time.

Page

Donate Now

More from Arts

Comments

*Comments will be moderated