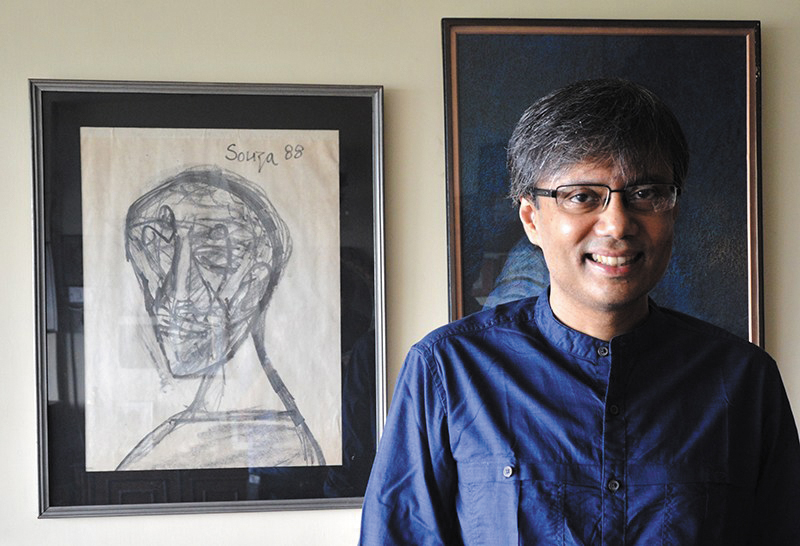

Amit Chaudhuri. Photo: Devdan Chaudhuri

Amit Chaudhuri is one of the most eminent writers of our times whose most recent novel is Odysseus Abroad. Among the many prizes he has won are Commonwealth Literature Prize, the Betty Trask Prize, the Los Angeles Times Book Prize, the Infosys Prize and the Sahitya Akademi Award. A fellow of the Royal Society of Literature and Professor of Contemporary Literature at the University of East Anglia (UEA), he is also an acclaimed musician and Hindustani classical singer.

Ever since my debut novel was published, I have been asked many times whether I am his relative. We both live in Calcutta, have the same surname and he has given a quote that is on the cover of my novel. But the answer is no. I first met him in person during a prize ceremony where my unpublished manuscript was nominated. He made me aware of the very first UEA Writers’ Workshop that was to happen in Calcutta and advised me to attend it. I took his advice, applied and attended the eight-day workshop where our tutors were Amit Chaudhuri and Romesh Gunesekera. This is how I got to know him.

Amit Chaudhuri lives in a South Calcutta neighbourhood with his wife Rosinka Chaudhuri — an academic and a scholar, their teenage daughter and his aged mother. His eighth floor apartment — decorated with art, artefacts, photographs and various curios — exudes a cultured and artistic milieu. A stone Ganesha statue sits within potted plants, paintings by Souza and Bikash Bhattacharjee hang on the walls, framed photographs line the side-cabinet and the furniture is all handmade in wood.

When I arrive at his apartment, we head outdoors to take his photographs. My idea was to click his photos with a couple of old buildings of South Calcutta's modernity. He has recently launched a well-publicised campaign to save the distinctive buildings of Calcutta's modernity, which are vanishing at an astonishing speed. However, during the time it took us to reach my car and return back to his apartment — it suddenly rained very heavily. But the moment we were back in his living room, the rain stopped and patches of blue appeared in the sky. He remarked that it happens to him a lot these days: whenever he goes out, it starts to rain. So we smile, leave the outdoor shoot to another day, settle in on the sofa and begin the interview.

DEVDAN CHAUDHURI: In the very first paragraph of your recent novel Odysseus Abroad, we find this sentence “he pounded the pillow and the sheet to ensure he’d dislodged strands of hair as well as the micro-organisms that subsisted on such surfaces but were invisible to the naked eye”.

Your oeuvre as a novelist is remarkably revealed in the sentence in a sense that you wish to lay the gaze of the readers to the aspects of the world around the characters of your novels which are seemingly invisible to the consciousness, but is ever subsisting within the fabric of reality within which the characters inhabit. Would you elaborate on this essential impulse that has led your writing to be compared with Proust, and more recently with Knausgaard, and has earned you a portrait of an artist as a memoirist?

AMIT CHAUDHURI: That’s a very well-formulated and insightful question. I have always been interested in things which may seem irrelevant. To give you an example of the irrelevant, I would like to point towards an essay by Partha Chatterjee, the political scientist, writing about, as he calls it, the “Sacred Circulation of National Images in India” — that is, I think, the title of the essay he once wrote. He talks there about the fact that if you look at the history textbooks of the first half of the 20th century, you see that the pictures of national monuments have certain details in them that one might call superfluous — like a person swimming in a tank, or a dog, or a man riding a bicycle; and these things are happening by the side of Taj Mahal or Qutub Minar or Red Fort. Then he notes that by the second half of the 20th century, the post-independence textbooks are gradually emptied of those details and all that you have are the images of the monuments. He speculates about why this happened — whether it was cheaper to produce such an image. No, he says, that’s not the reason. So he puts it down to certain national monuments acquiring a kind of religiosity, a kind of sacredness (I am now paraphrasing) which purifies the image and takes away the quotidian or random elements which don’t fit into the purity of that national image. And I have always been more interested in those quotidian elements, those accidental elements. So neither a picture of reality nor a picture of history to me is sufficient. It is always those random elements, those loose threads which are of greater consequence, for whatever reason. There is no clear reason to me why they are of greater concern. Therefore I am also drawn to those artists who deal with these loose ends. Like Arun Kolatkar, for instance, going to the pilgrimage town Jejuri, where he writes about the town precisely because it is defunct pilgrimage town, and more than its temples it comprises random details and activities and people that no longer fit with their original function. How does that randomness fit into an idea of sacredness? That is, the sort of “sacredness” that Partha Chatterjee is talking about, which reflects an ideal, or presents us with an iconic image. That is the question that Kolatkar’s book Jejuri poses.

So I have always been interested in the significance given to those random elements and things, which don’t fit into a history composed of significant moments. I would therefore say, as I have said in my essay about Arun Kolatkar, I am more interested in junk than I am interested in history. And like Kolatkar, for whom I believe history is junk (that is, unusable or useless), and junk (that is, derelict things) is history, I also often see history as junk, and junk as somehow being historical. This might be related even to my campaign to do with buildings in Calcutta, and which has less to do with landmarks, “heritage” and monuments. I have been trying to draw people away from the term “heritage” although it’s a default term and people will persist in using it. I have been trying to draw people to the streets, the neighbourhoods and the architectural multifariousness of middle-class houses that don’t qualify as landmarks or monuments. Because much of truest imprint of past cultural and historical efflorescences will lie in what we think of as everyday objects and spaces.

Interestingly, the essay I mentioned by Partha Chatterjee, on the role of the quotidian, is not the norm either in Indian academic writing or even in his own writing: it’s an aberration. What that fact tells us is that the Indians who have been theorising or thinking in the last fifty years haven’t thought too much about the role of the superfluous. Where I’m concerned, my relationship to the superfluous is, for me, life-giving and stimulating. So this is why, even in Odysseus Abroad, not only do you have a series of inconsequential events described during the day, you have those inconsequential events arranged in such a way that they have their counterparts in mythology, and also in the canonical texts such as Joyce’s Ulysses. You have those echoes occurring through the text, so that the irrelevant is also organised in a significant way on another level. And yet that other level is invisible, to use the word that you just did. So that other level is not easily accessible, but it’s always there. People need to be alert to that other level. However, I am not going to — I can't — give that other level on a platter to the reader. So the tension between what you see and what you don’t is always a powerful tension, as far as I am concerned.

DEVDAN CHAUDHURI: Finding associations or patterns between seemingly unrelated things is one of the prime aspects of creativity. How did Odysseus Abroad germinate within you? The novel is a new approach in comparison to your earlier novels, in regard to associations, and the way you have set off Ananda on a journey within a single day, where the past and the present are woven together, updating Ulysses with brevity in 239 pages, and also making a comment about a world bereft of any heroic adventures in Homeric sense.

And also, an insight about your process of writing, re-writing, till the moment you feel that a novel is done, from germination to the final draft.

AMIT CHAUDHURI: I have spoken earlier about what led to the germination of the idea that eventually led to Odysseus Abroad. I will describe it again. (He points to the painting on the wall). Here is the charcoal sketch done by F.N. Souza which I purchased I think in 2001 and hung it up over here. I bought it for fifty five thousand rupees — a dirt cheap sum for something like this by Souza, whom I greatly admire. I also think it’s the first artwork I’ve ever bought. Souza was alive then, but he would die the same year or the next year. My uncle on whom the uncle in Odysseus Abroad is based — though I would be wary of formulating it like that; anyway I have said it to simplify things — finally visited India and Calcutta after twenty five or even thirty years in 1991 to attend my wedding. When I got to know him better in London, as a student, he always said he felt no homesickness and had no intention of going back to India.

But when he came here after being persuaded by me to attend my wedding, he no longer wanted to go back to England. He actually loved being here; he loved the streets, the people and the relatives. He lived here with relatives, mainly with a younger brother. He owned no house here (or in London), yet he had a quite a bit of money; it’s just the sort of person he was. Ten years had passed since he’d arrived in Calcutta when I bought this drawing. He visited me and said, “Let’s take a look at the painting I hear that you bought for fifty five thousand rupees”: that to him was a large sum for a mere painting. He liked to show that he didn’t care about art, but he cared about it a bit too much, but sometimes cultivated the persona of a philistine. So he came here and stood before the painting and said you might as well have paid me fifty five thousand rupees just for farting! As is case with the book, the scatological references, the constant asides on digestion and bodily functions, were always there as part of his conversation, sitting oddly besides his references to Tagore. So it was a strange combination of things. I said to him, “This is a great painter, don‘t you see how wonderful this drawing is?” and he said, I grant you that sometimes what a genius produces and what an idiot produces looks exactly the same. I replied, “This figure does look a bit like you.” And the reason it looked like him was because Souza had done a self-portrait and Souza looked a bit like my uncle. Anyway, he went off, and I kept thinking about the fact that the portrait looks like him, and I also thought about the fact that Souza had named the picture “Ulysses”.

So I began to think — could my uncle be Ulysses, could my uncle be Odysseus? He in fact was a figure like Odysseus, a man who’d wandered far from home and taken decades to return, so I began to think of him as Odysseus, and, recalling my journeys to Belsize Park and ending up in that kitchenette, pouring a glass of water for myself, began to think myself as Telemachus, who set out to look for his father. That’s when I began to wonder if I could write a story in which I played Telemachus and he Odysseus. The art of Souza was the catalyst and then I toyed around with the idea for ten years. The conversation with my uncle would have happened in 2001/2002 and I started writing the book in 2012 and finished it in 2014, the year it was published in India. (It was published in the UK and US this year.) I thought for a decade about casting him as Odysseus and then I took the plunge. First I began to write it as a memoir, which didn’t quite work. Then I began to think of organising it as a story where the young man is playing Telemachus, the uncle playing Odysseus — a story set in London over a single day like Joyce had set his story in Dublin over a single day. So Joyce gave me the cue how to do that, and in that sense this novel would be an updating of both Homer’s protagonist and of Joyce’s Bloom, re-written in Bengali terms. As I was looking for correspondences, one of the first things that I thought of was the noisy neighbours I had at Warren Street when I was student in London in the early eighties, and who made my life so miserable. I thought these people could plausibly be the suitors in Ithaca who had made Penelope and Telemachus‘s life miserable. As the noisy Warren Street neighbours became the suitors, the other correspondences fell into place from my memory.

So remembering the myth of Odysseus, remembering Homer, also helped me to remember my past in London. The myth became a code for remembering my own past in London. It was as if it had all been there, waiting to be reclaimed — the correspondences with The Odyssey; already there without my realising it. And also the correspondences with Joyce — all the stuff to do with bodily functions, digestion, the insides of the body, shitting — all of that — eating, in Joyce’s case eating kidneys, and in my uncle’s case it was consuming liver. And then in Joyce’s case the preoccupation with another kind of journey — metempsychosis — the journey of the soul, transmigration of the soul, and similarly the uncle’s preoccupation with the afterlife, with ghosts. These were all there; all the coordinates were already present. I had to discover the coordinates to see how much of The Odyssey and of Ulysses were already there in my memory of that time.

Amit Chaudhuri at his Calcutta residence. Photo: Devdan Chaudhuri

DEVDAN CHAUDHURI: It is just like what Jan Skácel wrote, that “the poem is somewhere behind, it’s been there for a long time, the poet merely discovers it.”

AMIT CHAUDHURI: Yes, it was like that. I discovered it; I didn’t have to invent it. Thinking about the two books became a way of remembering that time. The first convergence was to do with the drawing, and then the other convergences fell into place. The whole business of convergence is a strange thing; for me convergences have happened before, it happens in all your books. Even to find two dissimilar things suddenly become similar through the simile or the metaphor is something that always preoccupied me from my first book, A Strange and Sublime Address, which is full of metaphor and simile. But they shape my music project too, finding commonalities between Raag Todi and the riff to Clapton’s Layla — one of those accidental moments when different things seem the same. Those convergences have happened a lot in my creative life, either through remembering or listening or doing two things at once, as with singing Raag Todi one day and hearing Clapton’s Layla in those notes: that is to listen and to remember simultaneously.

This whole business of noticing similarities which seem coincidental is something that creative people and mad people are susceptible to, I’ve been told. Let’s say you are thinking about something and then thinking hard about it. You might be in a state of distress, while you are thinking about it, and the next moment you see a sign in which you see that word. It has happened to me a lot of times. And somebody I know, who is an extremely creative writer, a Canadian woman, who has also suffered from psychotic episodes, told me that both people who are on this verge of madness — because of whatever condition they have — and creative people are vulnerable to noticing coincidences.

I remember coincidences in my life that don’t mean anything, don’t add up to anything, but have this ominous kind of import. I remember I had to have a major operation when I was in Cambridge — I was teaching there — and I had to have heart surgery. The surgery would happen in Papworth which is a nursing home totally devoted to heart surgery and cardiology. I was going to go there in a week to be operated upon. It was a horrible day. My parents were there; my wife and I were walking in the rain and both of us, I think, were thinking about Papworth. Suddenly a taxi was passing by and it stopped. And a person leaned out. By the way, people rarely ask you for directions in the UK — they use maps. But this person asked, “Can you tell us the way to Papworth?” That kind of thing happens now and again, seemingly adding up to nothing. On another level, one has creative convergences.

DEVDAN CHAUDHURI: And also, a bit about your process of writing and re-writing. Do you rewrite a lot? What is the process you follow?

AMIT CHAUDHURI: I mostly write in long hand. When I write a novel, I write in long hand. Let’s say I write a paragraph. I generally don’t write the next paragraph before I have thoroughly looked at the paragraph I’ve just written. I cannot proceed until it works for me as a piece of writing. It would rarely work for me as a piece of writing in the incarnation in which it has been put down. I will have to usually scratch out words, take out sentences etc. Maybe add things, but often take things out for it to begin to make sense.

Once I have written, let’s say, a series of paragraphs or a page and a half of a chapter, I will go back to the beginning and look at it once again to see what it seems like now, and then I will work on it again. There will always be two words or three words in each paragraph or maybe a word in each sentence that I don’t like anymore, which is not doing the work it was supposed to do. Then gradually I will put the book together. I am not talking about facing other kinds of structural problems for the moment. I’ll finally type it into a computer. As I type it out, I get a sense of it in print, and I will then have another view of it, about which words are working, which words aren’t, which sentences are working. Then I’ll perform another act of revision.

DEVDAN CHAUDHURI: Is it important for you to get the first line right? Often novelists say that the first line is of prime importance, because everything else follows from that.

AMIT CHAUDHURI: It’s true to a certain extent. But I think too much is made of first sentences nowadays. I think it’s because the first sentence has become part of creative writing teachers’ ten pointers towards writing a successful novel. People are heavily dependent upon formulae which can be taught in creative writing classes these days. Nobody ever wrote a great first sentence thinking, “I must write a great first sentence”. Besides, every sentence is a first sentence to me.

DEVDAN CHAUDHURI: Do you show your work-in-progress to anyone and take feedback? Do you respond to suggestions which others offer?

AMIT CHAUDHURI: I try not to show work-in-progress to anybody, unless there is some pressing reason to. Sometimes, if I am feeling low about a piece of work, and I am at a stage when I don’t know whether I am doing the right thing, I speak to my wife about it. I take her views seriously, but the final call about what I do is mine, it’s my decision. In the end I don’t care about what others have to say. This is what I say to my creative writing students, it doesn’t matter what others are saying; you will have to decide whether you are happy with the work or not. If you are not happy with it, no amount of praise will make you happy with it. But I will discuss what I am doing with my wife. That might clarify what I am doing — by simply talking about it. Because one would have several impulses when one embarks on a piece of writing. It’s not only one impulse; especially in my work, where it is working in my head in various ways. It is not about getting a plot onto a page. So in my head it is working on various levels; I am trying to do a juggling act. And I am concerned whether I am able to hold all the elements together.

Sometimes I lose sight of some of the elements, and the narrative threatens to become one kind of a story, rather than a story with various kinds of ramifications. So then just to talk about what I am doing is going to help in clarifying what I am doing. Switching off completely also helps. Take a gap, take some time off it. Every evening I do something — this advice is directed to my self — that has nothing to do with writing. Like watching HBO; nowadays there is much more than HBO: usually watching something that doesn’t require mental energy. Even then of course you are thinking about writing; there are no writers who are trying to make a certain path for themselves who are not also thinking, in some sense all the time, even when they’ve switched off, about writing in the way they are, and why they are on this particular path. Often, it would be nicer to be on a pre-made path, a pre-fabricated path — it would be easier to go down there. Just in case you are not, then you are always at some level thinking about what you are doing, whether you went down the right path or not. So on some level, you have to make a special effort to consciously switch off as well.

DEVDAN CHAUDHURI: Do such doubts come to you even after writing so many novels? Haven’t things become easier?

AMIT CHAUDHURI: It hasn’t been easier. But what’s become easier is to understand what one was up to. Why I do various things? Why I wrote novels in a particular way? Why I wrote the essay? What are the discrete or separate selves which engage in these activities? Why am I even the kind of person I am? What is it in me that suddenly draws me to do something about the Calcutta houses? What is the thread that runs through these things, without wishing to homogenise these various personalities? Now it becomes a little easier given the multiplicity and the amount of stuff I have done. To understand what I have been up to makes a little kind of more sense at least where I’m concerned. But you are always trying to create that space for yourself, create that audience for yourself.

DEVDAN CHAUDHURI: Kundera, in his coruscating The Art of the Novel, pointed out, “All novels, of every age, are concerned with the enigma of the self... How can the self be grasped? It is one of those fundamental questions on which the novel, as a novel, is based.”

All your novels, in my view — to go beyond the “memoirist” interpretation — are also an attempt to grasp the self. But a self that doesn’t need great conflicts — either external or internal — to grasp itself. Neither does it need special circumstances to reveal itself in what Sartre called the “theatre of situations” — exemplified by Kafka. In your novels, the self is grasped through family, through habits, through subtle reactions, through mundane rhythms of life, through objects. Does this unique method of grasping the self with the most ordinary —that I am hoping to be the first one to point out — an unconscious impulse or a deliberate novelistic innovation?

AMIT CHAUDHURI: I really don’t know. I also don’t know what grasping the self means.

Amit Chaudhuri at his Calcutta residence. Photo: Devdan Chaudhuri

DEVDAN CHAUDHURI: Grasping the self means understanding the self of a character; a sudden revelation, an insight of the self in certain situations of life and existence. What a character realises about himself or herself, or how the author deals with a character in a situation or a scene, that makes the readers understand the self of the character, its condition, its enigmas. Also the usage of different tools and methods to show or grasp the self.

AMIT CHAUDHURI: I haven’t thought much about this. But let me answer in two stages. There’s something that I have been more conscious about, been aware of, only in the last few years. One thing I am interested in is writing itself. And I am interested in exploring anything, however slight it might be, and see whether it can be written about, and made to, in some way, seem compelling. I am interested in the feeling that anything can be turned into a piece of writing, or a piece of cinema or a picture. I am interested that a director like Ozu often made films about nothing, about very little. And he managed to show us that such films could be made. I am interested that Kiarostami — the Iranian filmmaker — often began his best films on very flimsy premises. And seems to be aware that he is going to test the role of filmmaking and the capacities of the filmmaker to see whether the filmmaker can turn something that may seem to be insignificant and unpromising into a film. Similarly, readers or people who partake of culture, and who give value to things, also give value and significance to certain things which are, by themselves, boring. The boring might suddenly become engrossing. This might happen to you and me if we sit down and begin to look at CCTV camera footage. The footage as viewed by security personnel will have a particular kind of interest — either interesting or for the most part boring, because the things they are looking for are not happening there; boring, and therefore, not to be worried about. But, if you and I have an access to the same footage, we might find it increasingly fascinating, and continue looking at it for about twenty minutes, after which our attention might begin to wander.

It’s also to do with testing our attention — how can I continue to attend to something and transform it, and find hidden connections and meanings within what we see. That too is the question — how far can we test the attention? So you and I if we sit together, we might have different thresholds in terms of how long can we watch CCTV camera footage, and how long can we continue to find it interesting. Maybe during the first three minutes we may both find the footage completely boring and meaningless. After the third, fourth or fifth minute, suddenly convergences and patterns will begin to emerge.

Connections between the people we are seeing in the footage and connections with our own lives, which are not sort of obvious personal connections, as you might have, let’s say, upon watching a film about a young boy whose parents got separated — or whatever the context is. That’s a personal connection. But in the CCTV footage you are not looking for those personal connections, but other meanings will emerge which you will create, other patterns which connect your life to that life, and those lives to that space and to each other. And slowly that piece of footage is going to become fascinating and you are going to keep watching it, until, at a certain point, you will again reach a point you were in the first and second minutes, when it becomes boring and you cannot watch any more. That’s the kind of thing I am preoccupied with. What can we do with something like that? And how long can we test our attention? How long will the attention continue to give meaning of a certain kind to what is being presented to us? Those are the thresholds I am looking at. That’s one thing.

The other thing to do with the self is that I remember one of the things which I wanted to do is to escape the self. I will use the word “self” and the term “escaping the self” with wariness because I know that these are slippery terms. The “self” itself is a slippery term — different people might mean different things by it. Over here I mean it in the sense I used it as a teenager, and my teenager’s sense of what the self was especially in the way it emerged out of books and the intellectual ethos of the time (the late seventies). I was a precocious teenager, so by the age of sixteen I had become aware of Sartre, Beckett and Camus; in film, one was aware of Bergman. It was the late seventies; all the artistic, aesthetic and intellectual buzzwords had to do with a particular metaphysics of the self and giving centrality to the self and its journey. So the two terms which were in circulation then were “existentialist” and “absurd”. There was the drama of the absurd by Ionesco and Beckett was appropriated into this discourse. Existentialism was vulgarised and used in lay discourse in a lot of things; it became popular, and even Hindi film stars referred to “existentialism”. And both these words emphasised the protagonist and the self, and

Page

Donate Now

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated