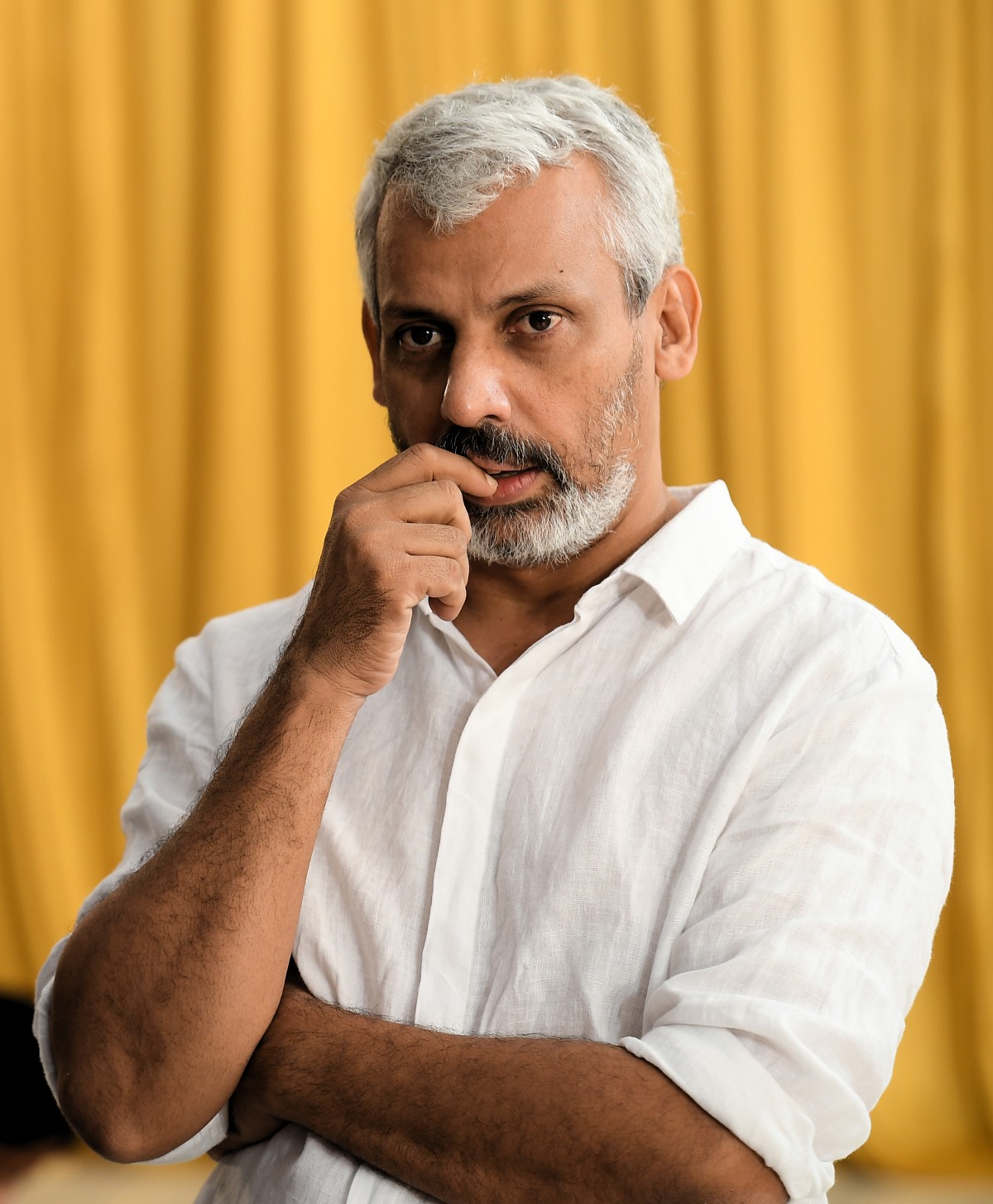

Anees Salim, author of The Odd Book of Baby Names. Photos courtesy of the author

The author on his fascination with kings, especially the fallen ones, that served as the genesis for his novel, The Odd Book of Baby Names, and the nine progenies of a dying king who feel betrayed by their father

In Anees Salim’s epistolary novel, The Small-Town Sea (2017), the thirteen-year-old protagonist is uprooted from a teeming city and is forced to move to his father’s town after the dying patriarch shifts his family to a seaside town. In his new novel, The Odd Book of Baby Names (2021), we meet a dying king in a bustling city, where nine of his children recount, in alternating monologues, how their father betrayed them.

The big city Salim — arguably India’s most underrated writer (his lush and enviably evocative prose, shot through with rapier-like wit, sparkles; this means that he should be more visible and written about more often, but the incorrigible recluse that he is, he has chosen to remain notoriously private) — brings to life has been present in his previous novels — The Vicks Mango Tree (HarperCollins), Tales From A Vending Machine (HarperCollins), The Blind Lady’s Descendants (Amaryllis) and Vanity Bagh (Picador India) — in some way or the other. In an interview to The Punch Magazine in 2017, Salim had said that he loved constructing places inside his head. Like his other books, The Odd Book of Baby Names, too, is drawn from the deep well of his lived experience. His latest, The Bellboy, which has been published in the UK by Holland House Books, is the story of a 17-year-old boy named Latif, who works as bellboy at a hotel where people come to die; his life is altered after he stumbles upon a corpse of a small actor. Excerpts from an interview:

Shireen Quadri: In Bellboy, you return to Varkala, the coastal town in Kerala you grew up in. From the craft’s point of view, how different is this novel? How central is the town and the beach to your consciousness?

Anees Salim: The Bellboy is set in Kerala, but not in my hometown. As the backdrop, it has a small, sinking island some forty miles north off my town, and it is about a seventeen-year-old boy whom I knew vaguely and a lodge that was in news for wrong reasons. There is a waterbody that plays an important part in the book, but it’s not the beach I have written about in two of my books. In terms of craft and construct, it is completely different from my last book.

Shireen Quadri: The Odd Book of Baby Names, your sixth novel, has been teased out of the story of a real king, Mir Osman Ali Khan of Hyderabad, one of the last kings and the seventh Nizam. Though he remains unnamed, there are enough clues for the reader to arrive at this conclusion. He was believed/rumoured to have sired over 100 children from the 86 mistresses in his harem, next perhaps to Sultan Moulay Ismaïl of Morocco, who made it to the Guinness Book of World Records for having fathered hundreds of children — perhaps more than a 1,000. What fascinated you about this rather flamboyant character who had made it to the cover of TIME magazine (1937) for being “the richest man in the world”?

Anees Salim: Kings have always fascinated me, especially the fallen ones, which is to say I am fascinated by the life and time of every Indian king. Whenever I am in the vicinity of a palace, I try to picture the life behind those high walls — the life before and after the abolition of the privy purse. About two decades ago, I lived in a city that was once ruled by a king who was famous for his eccentricities, debaucheries and magnanimity. The king was long dead, but he was still loved and revered in the older part of the city, where I met impoverished people who were rumoured to be the direct descendants of the former ruler. The most interesting of the king’s illegitimate children was a taxi driver who had a fancy name and a little dingy house. His story, which he was really proud of, triggered my interest and I started to do some research, and the more I learned about the king, the more incredible his personal history turned out to be.

Shireen Quadri: The novel is told through a multitude of nine voices — progenies of the king, all. Each of them has a story and tells it from his/her perspective. Did the novel come to you in the polyphonic form? How did you go about working on the particular tone and tenor of the many voices — funny, disturbing and desperate, and each with their quirks and complexities — that jostle to be heard in the novel? Did you have to work on the particular manner or style for them to tell their story in a manner so that it circles back to where they come from and what role they play in the larger scheme of the novel?

Anees Salim: When I started writing this book, I was not sure if I would be able to complete it. But I could never imagine this book without multiple voices. The challenge was to create nine entirely different entities, to speak in nine different voices. In the first couple of drafts, every character sounded somewhat similar, only their stories differed. But from the third draft, each voice started to gain individuality. My confidence was crushed when a few friends read the manuscript and advised me to switch to a single voice narrative. But my editor, Manasi Subramanian, said the book was perfect in its current form, that she could not imagine the book without multiple voices. And I suppose her conviction worked.

.jpg)

The Odd Book of Baby Names

By Anees Salim

Hamish Hamilton

pp. 288, Rs 599

Shireen Quadri: You tell the king’s story when he is on the brink of death, comatose and stubbornly clinging to life: the suspense around his imminent death lends the novel a sense of momentum. His kingdom having slipped away, the king lives in the fading shadow of his erstwhile glory, taking his last breaths in a democratic India. The core of the novel, however, is not so much historical as it’s emotional; even though it’s about a historical character, his crumbling world foreshadows people who have been forgotten. Though the novel’s pivot is a dying royal figure and the palace is a significant part of its setting, it is not so much about the royalty as its heart lies with the commoners — it’s in the streets that it comes to life. Did you set out to tell the story of the ordinary people, contrasting the worlds of the king’s legitimate and illegitimate children: a life of luxury and privilege and riches against that of poverty and hunger and despair?

Anees Salim: I know almost nothing about the way kings lived. But my belief system says when a writer doesn’t know too much about his subject, he is liberated, he is free to create the world the way it pleases him. So, I set out to write this book with same kind of excitement with which a child confronts a connect-the-dots game, only that I had only nine dots to play with, and each had a different size and definition.The common thing was the line that connected them; the lineage. When the dots were finally connected, they created a kingdom where the privileged and the commoners lived in the same state of despair and suffered almost the same way.

Shireen Quadri: All the king’s children — Moazzam, the drunkard and the favourite son, and Azam, the prodigal son, who live in the palace, and others like Sultan, the prince of marbles, and Shahbaz, the prince of words, “the poet who looked like a potter when he didn’t look like a painter” — are eccentrics and oddballs. The lone prominent female character, Humera, struggles with depression and is given to talking with inanimate objects in her house — doors and windows. Did you consciously work on making these characters slightly kooky in one way or the other?

Anees Salim: I think when we are surrounded by people, we all put up a show of being normal. We mimic normalcy. In private, we are all oddballs, we act in weird ways. The Odd Book of Baby Names is essentially about nine people who feel betrayed by their father in different ways, and they confide in the reader in their monologues, without inhibitions and prejudice. To me, they are normal people behaving in a normal way.

Shireen Quadri: The two characters that stood out for me were Zuhab and Humera. There is a touch of magical realism to the way they tell their stories. In a novel that is stylistically different from your previous ones, you are able to carry out linguistic experiments through Zuhab: his sentences follow no punctuation, reflecting his unfamiliarity with the language and his rustic background. He is also someone invested in the act of storytelling. “When my story starts boring you please tell me, brother. We take a break. I make you some tea I start again and you listen carefully again,” he tells us at some point. Is his preoccupation your own as a novelist: do you fret over making your novels gripping for readers? Another fascinating aspect of the novel is the way you have captured the doomed love story between Humera and Shahbaz — it is both refreshing and inventive. How did you conceive of this particular fragment?

Anees Salim: Yes, Zuhab is the alter ego of the raconteur in me. I do everything possible to keep the reader engaged. I attempt to create a sense of mystery around my characters so that the reader stays with me, and I think that is what every storyteller does with varying degrees of success. Zuhab narrates his story through long sentences which pay little respect to punctuation. The idea was to convey his anguish through his breathless voice. I have applied a similar kind of treatment to Hyder as well; his narration is repeatedly broken because of his stammer. In a book of polyphonic structure, mannerisms of each character count a lot. I think the techniques I have used worked decently for me.

As a rule, I don’t write love stories. I envy those who do. But I did enjoy writing the sections where Humera and Shahbaz appear on the promenade together. Those were the easiest chapters to write because I was just copying them from my own past. I modelled Humera after a girl I used to know, who would be reduced to tears by almost everything I said. And I modelled Shahbaz after myself. It was a difficult relationship, but it was addictive at the same time. For me, writing about Humera and Shahbaz was like revisiting a personal museum of love and looking at old pictures with a faint sense of loss.

Shireen Quadri: The novel is quite haunting in its imagery, which makes it tremendously memorable: the Wall of the Erasers, the twang of marbles on the floor, the bench near the lake with a carved shape of the heart in the park where Humera and Shahbaz meet, the king passing wind on the bed in Cotah Mahal, the descriptions of Nizam Tailors and Bada Topiwalla, and Wali Miyan’s teashop, where the poor feel at home. Did its visual landscape weigh on your mind when you are working on it? Did you have to craft them in a way that they are imbued with a sense of mystery and melancholy?

Anees Salim: While writing this book, I mentally lived in a city I had built with words. I walked its narrow streets every day, sat under its ancient trees, wandered around its slums, lingered by its lake, and finally went to a big railway station and waited for the train that would take Zuhab home. Once the book was written, it took me an effort to get out of that city, to walk away from its ruins. I think I still carry a tiny part of it with me. I am not sure if the city was shrouded in mystery, but it indeed had a touch of melancholy to it. I suppose every city looks crestfallen just before sunset, and in The Odd Book of Baby Names the sun had long set for the dying patriarch and his descendants.

Shireen Quadri: Like most of your novels, The Odd Book of Baby Names, too, eventually hurtles towards tragedy, but the sense of tragedy is leavened by humour in interesting ways throughout the novel. This, of course, has come to be known as your forte, just as your preoccupation with sadness and death. What is about levity in moments of tragedy that attracts you? How do you work on this element?

Anees Salim: I have been repeatedly asked this question. And I don’t have a clear-cut answer for this. Maybe blending sadness with humour is something that happens naturally to me.

Shireen Quadri: Most of your novels have sprung from your own lived experiences. ‘Write what you know’ has been a refrain taught in creative writing schools for long. And while there is some merit to this dictum, it is also true that works of imagination can come from worlds well beyond the lived experiences of a writer. Since most of your characters are Muslims, do you see yourself as better placed to tell stories of people of your own community — their anguish, anxieties and ambitions, their hurts and heartaches? While writing specifically about the splintered families of a particular community, do you ever have to worry about being typecast or pigeonholed, even though this typecasting can mark you out from the rest in a good way, too?

Anees Salim: My first book, The Vicks Mango Tree, had characters from all religions, and while writing it I realized that my Muslim characters were more defined and better sketched than the rest. It was this realization that inspired me to rediscover my background and work on ideas I could easily relate myself to. And, to the best of my knowledge, very few writers in India set their stories in Muslim backgrounds. I feel more at home when I write about the struggles and apprehensions that Muslims face. I think that is my space, and I believe there are enough stories to be told about this particular community without sounding repetitive.

Shireen Quadri: Your trajectory as a writer has been unlike any other Indian novelist writing in English. With six novels, you have carved out a place among the finest prose stylists of India. It was through your third book, Tales From a Vending Machine, that your writing career took off — and that too when you approached an agent under the pseudonym Hasina Mansoor, who became the protagonist of the said novel. In hindsight, how do you look at your beginnings? What is your assessment of the contemporary Indian novels in English?

Anees Salim: The protagonist of a book querying a literary scout was a risky idea. But it worked beautifully for me and earned me the much-needed break which many of my ‘well-written’ query letters had failed to. My only regret is that except for Jai Arjun Singh, no one gauged the real depth of the character and the undercurrents of the book.

I think Indians writing in English are doing a fabulous job. But I wouldn’t restrict good writing to Indian writers alone. Look at what the writers from Sri Lanka, Pakistan and Bangladesh are doing.

Shireen Quadri: In an age when writers can’t tire of tom-tomming, you remain notoriously reclusive, even though you are quite active on Facebook, regaling us with your trademark wit and sarcasm. When you began your journey as a writer, you famously refused to do any book tour. Do you see yourself as slowly, and willy-nilly, shedding that image?

Anees Salim: Deep inside me, I don’t want to change. I do get invited to literary fests and book tours, and I politely decline. I still can’t stand cameras, microphones and podiums.

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated