Arshia Sattar. Photo courtesy of Penguin Random House

Writer and translator Arshia Sattar on her oeuvre and the significance of knowing other people’s stories — ‘our only chance to seed a proactive humanism that is the only possible antidote to this hate-filled world’

The monsoon clouds had just begun to break over Pune when I first moved there. The city I had spent some time in as a child but now, several years later, it was a place where I knew no one. And so, as one who is without much company, I accompanied my mother to places she had been invited to only because she wouldn’t drive. On one such evening, I found myself in a room of 20 odd people, none of whom I knew, but all of who knew my parents in some past moment. At the far end of the room, surrounded by palms and fichus on a diwan covered with a patchwork bedspread, sat a woman whose hair reached her waist and a man who’s mustache could be measured with the palm of your hand. That was the first time I saw Arshia and her husband Sanjay — two people who would, unknowingly, change the way I thought and felt and saw and listened. I had very recently graduated with a degree in English Literature and had read Virginia Woolf and T S Eliot, Yeats and Auden, Tennessee Williams and e e Cummings. And I thought I had read whatever needed to be. But Arshia and Sanjay talked to me about jazz and food they had eaten, about Indian writers who wrote in English, about the Bible and about how good their whiskey was. That evening made me thankful for being in Pune at that moment when Sanjay and Arshia were.

Some years later, I attended a workshop Arshia was conducting on the Valmiki Ramayana, a book that I had not read but a story that I had, like many Indians, known. Arshia led us through her translation, stopping only to listen to what we thought. After the week was over, I lay in bed, barely eating and not bathing, only reading this translation. And in the days that were filled with metaphors of moonlight and forgetting, my life began to change. And Arshia was there.

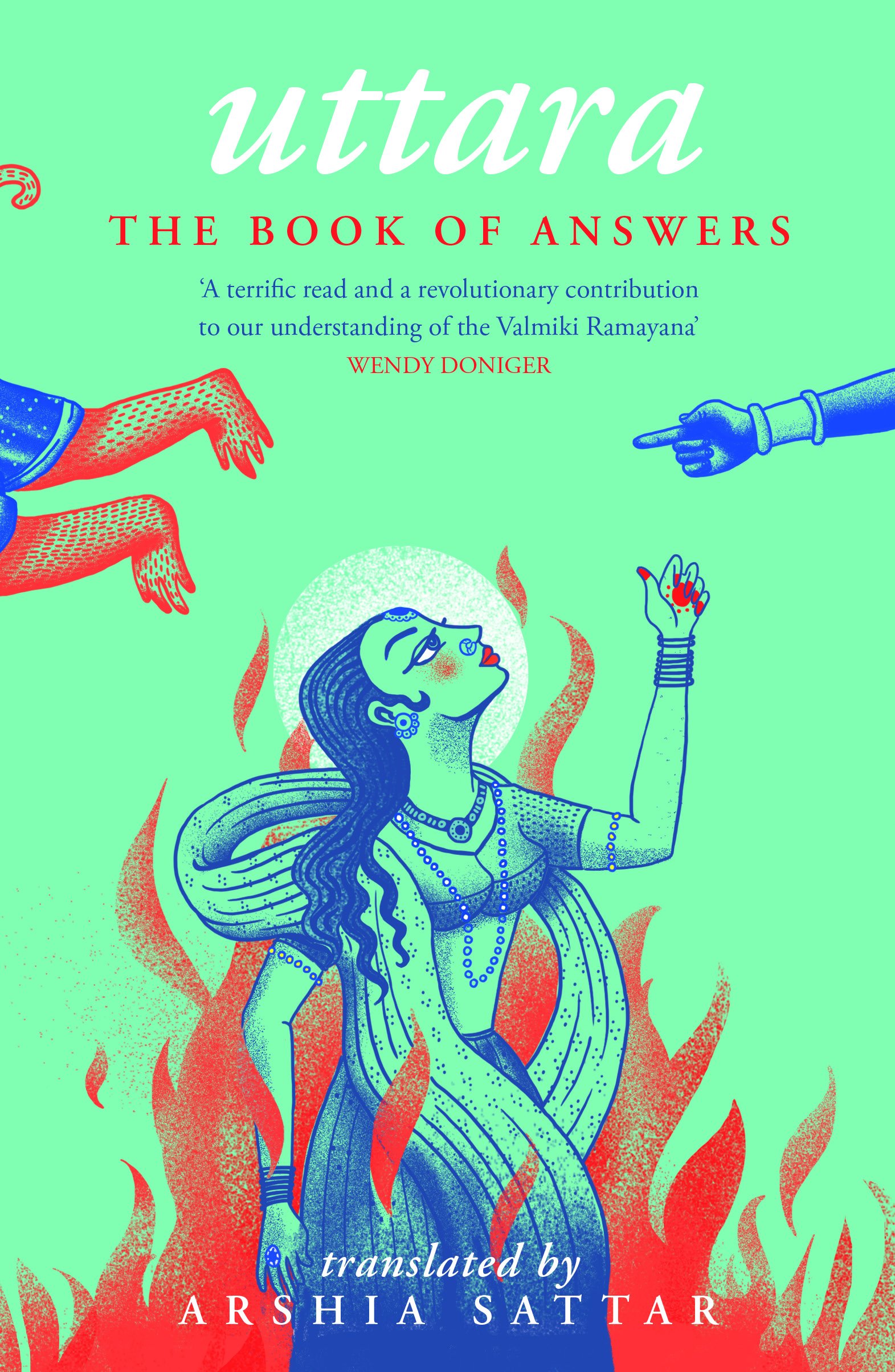

Many of us who are familiar with Arshia know that The Ramayana is a book that fills her dreams and her occasional, strange, encounters with monkeys reaffirm this relationship. When Arshia translated the Valmiki Ramayana in 1996, many of us who ‘knew’ the story had known it because Doordarshan had told us one version of it; the demolition of the Babri masjid had drawn it back into public consciousness and the Rama who we imagined was a man who went to battle. Those of us who went on to read Arshia’s translation found a Rama who was wholly different, who was caught between two worlds and had loved and lost in equal measure.

Valmiki’s Rama was a man who had been pained by his wife’s abduction and who spoke of love in metaphors of a still lake in which a single lotus bloomed and caught the rays of the sun within it. In the 30 years that Arshia spent with The Ramayana, she thought about it, wrote about it and talked about it in India and abroad, crossing vast oceans with the story that was ‘always already’. And with every moment, like an artist, Arshia carved out of this 3,000-year-old story facets that we would ordinarily have not seen. Later, she wrote Lost Loves: Exploring Rama’s Anguish, a book of essays that distilled the ways in which she thought about the Ramayana, a book, that I think is only a peek into the workings of her mind. The essays explored Rama and answered deep existential questions about the worlds that he encountered, where places became metaphors for larger questions and characters became constellations that mirrored Rama’s anguish.

But this is a story about Arshia, about her oeuvre that stretches far across the horizon of The Ramayana world. And, beyond it, lie her other writings, her translation of The Kathasaritsagara, for example, a book that she translated in the early 1990s, some 70 years after it had first been translated. Arshia’s translation of The Kathasaritsagara keeps the frame of the story, keeps moments that are the essence of a Sanskrit story, repeats and retells instances just as Somadeva would have when he first wrote it in the 11th century. And that is what great translations do.

Sometime back, I read a poem by an Australian poet and it went like this:

“The Red-

tailed Bedouins

of Poetry, black

cockatoos embroider

the sun into us,

seam-rip asunder”

I wonder sometimes about the act of translation, about the moment of choosing the right word that will allow it to breathe in a century closer to us. Arshia’s work as a translator is that ‘red tailed Bedouin’, carrying with her the nature of time, through stories and songs that have crossed borders that are physical and intangible.

During my conversations with Arshia, that have often lasted long into the night, I have always wondered about the act of translation, the moment that encapsulates word in time — in the present through a deep understanding of the past. I imagine the translator can sense the intangible, feel the way a word moves along the page, sense when the moment must emerge faceted and full of intent.

At another point in the horizon, Arshia set up Sangam House with D W Gibson, a writers’ residency that shares its space with Nityagram, where writers, poets, playwrights and translators are given the luxury of time to immerse themselves in the written and the performative spaces of the arts.

As I write this, my nieces and nephews are packing a basket with cake, lemonade and a blanket and making their way to the far edge of the garden. And I am reminded of an article Arshia wrote on reading Blyton as a child:

“The world that I compulsively escaped into when I was a child had trees I had never seen and birds I had never heard and it seemed as remote from my world as another (lonely) planet could be. Which made it all the more magical.”

Arshia is always close.

Excerpts from an interview:

Imran Ali Khan: I remember hearing a story about a monkey that walked into your house in Bangalore and put his hand on your manuscript of the Valmiki Ramayana. Your relationship with the Ramayana is over 30 years old. I was wondering if you could talk about the early days of this relationship.

Arshia Sattar: The early days were really all about Hanuman. I chose to write about him for my MA thesis and then wandered off into other texts and ideas until I came back to Ramayana for my PhD dissertation. I guess that’s when the relationship became more intense — I started translating the Hanuman parts of the Sanksrit text. But I was a pretty poor Sanskrit student and I’m still a bad Sanskritist, so those were not easy days. So, I didn’t really get into the whole text until Penguin commissioned the translation. And then I fell prey to its wonders.

Imran Ali Khan: Your translation of The Ramayana in 1996 is an abridged translation. When you translate a text as important as The Ramayana, how do you decide what should be kept and what should be left out?

Arshia Sattar: My principle for abridging was really mundane — Penguin wanted 700 pages because that’s what a paperback binding would hold. And so I made the decision to translate for the ‘main story,’ as it were. The biggest cuts were in the Bala and Uttara Kandas, which at the time, did not interest me. And, of course, the Yuddha Kanda, which is a series of battles with not much significance (unlike Mahabharata where who kills whom is very important). And now I realise that I should have paid more attention to the Uttara Kanda. I think you abridge for yourself — you keep the parts you like and the ones that disturb you and make an informed judgment about what is ‘important.’ And I think that’s a good rule of thumb — you will always be telling the story with sincerity. That’s what’s really important.

Imran Ali Khan: The beauty of the Ramayana and of your translation of the text lies in the metaphors of moonlight and the descriptions of the monsoon season and the drunkenness of the monkeys. Your translation is precise — how do you choose the words, draw out the metaphors and allow the text to sing in a medium that is so contemporary.

Arshia Sattar: Yes, the moonlight metaphors are quite gorgeous. And the drunken monkeys are just a delight. Valmiki’s Ramayana has so many voices, so many textures, so many spaces that you can simply fall into and roll about in. I think you choose words out of your own experience — I know what the moon looks like in Indian skies, I’ve seen monkeys run and play and break off leaves and branches, I know the sound of the rain and the smell of the earth. Lots of words also come from reading — you know that moonlight can sometimes be ‘silver’ rather than ‘white,’ that someone ‘charged’ rather than ‘ran.’ And I also know other translations of the same text — other people’s words are always in play, either because you feel they work or because you know they don’t. But mainly, you have to see the pictures in your head in order to describe what you are reading — then you’ll know when to use ‘silver’ instead of ‘white’.

Imran Ali Khan: Your essays on the Valmiki Ramayana, Lost Loves: Exploring Rama’s Anguish, is a collection of essays that study the psychological landscape of Rama’s mind and his relationship with Sita and it is Rama who becomes the focal point of these essays. In your introduction to these essays, you talk about being a “card carrying feminist” who is “shocked that it is he (Rama)” who draws you in. I wonder if this allowed you to be more critical of his character.

Arshia Sattar: Well, that’s exactly it. The story is called ‘Ramayana.’ It’s about him. We can’t say we’ve understood the story or encountered the text as women and as feminists if we don’t take Rama into consideration. It’s very easy to dismiss him and his actions — and we can continue to do so even after we’ve thought about what he did and why. But we have to think about what motivated him, how he felt before and after. Lost Loves is deeply empathetic towards Rama. Other people have said that they are surprised that they are able to put away their hostility towards Rama, at least for a little while, when they’ve read the book. That’s the surprise for me even now — that it was possible for me to suspend judgment (as a woman and as a feminist) of a man who was repeatedly cruel to his wife, a wife he loved more than anything else. Obviously, it’s still not possible to endorse what Rama did, but we can think about why he did those things rather than taking them at face value.

Imran Ali Khan: At the end of the battle in Lanka, Rama asks the gods a question that will change him and our relationship with him. He asks, “Who am I and why am I here?” The answer to this question changes the past of the narrative, but also the future of it within the Uttara Kanda. In your translation of the Uttara, do you find his sense of self altered?

Arshia Sattar: Oh, absolutely. The Rama we see in Uttara Kanda is an entirely different person, a combination of a king and a god. He doesn’t act as a god in the Valmiki text, but he certainly acts as a king — it’s as a king that he has to kill Shambuka and as a king that he has to banish Sita. He seems really passive in the Uttara Kanda, surrounded by Brahmins, listening to their stories and allowing them to direct his thoughts and actions. He is no longer a warrior and he can no longer act only for himself. To me, Rama does not seem either comfortable or happy in the Uttara Kanda. And of course, once Sita disappears into the earth, he is utterly bereft and seems to only go through the motions of kingship, even of god-hood.

Page

Donate Now

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated