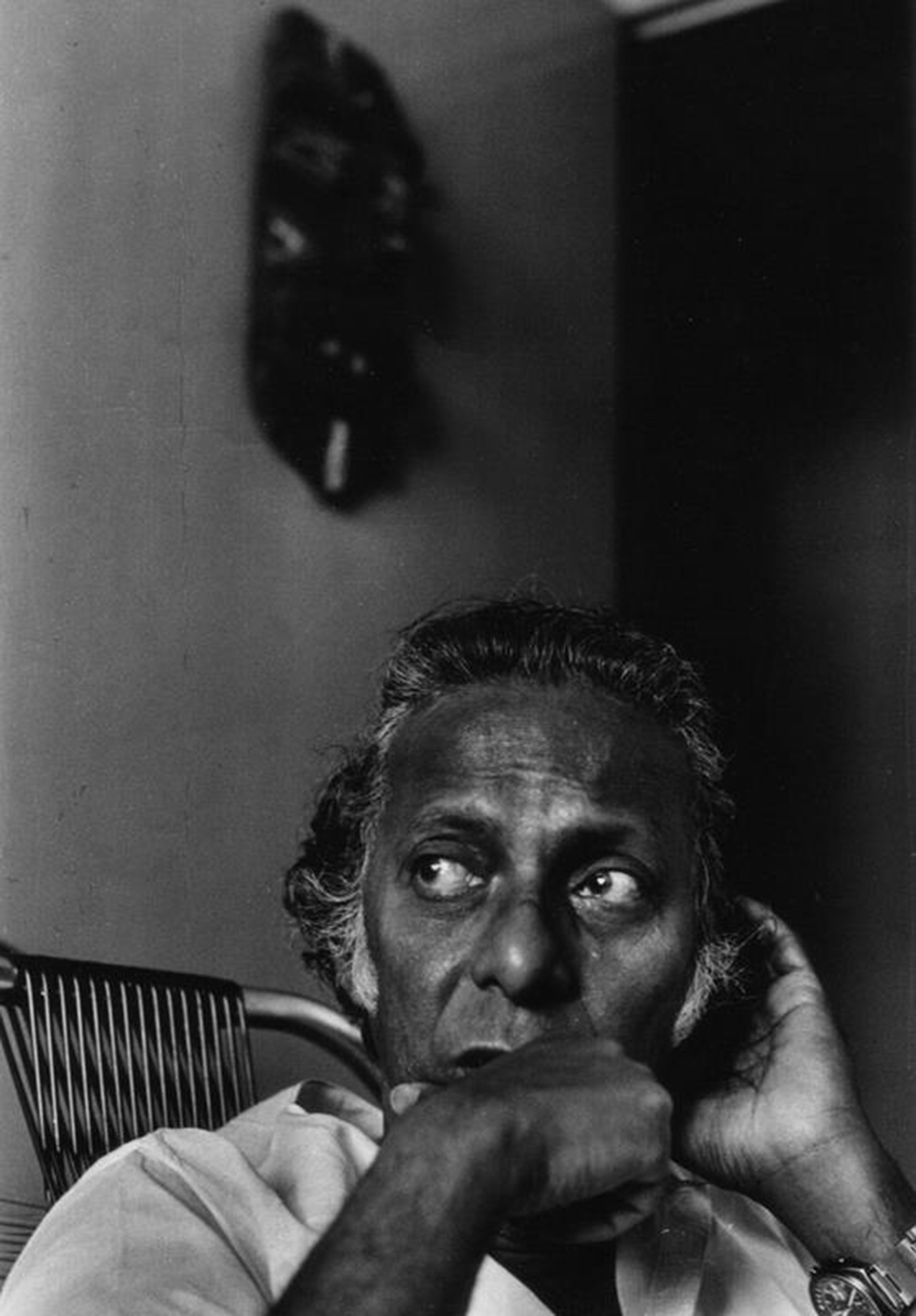

Mrinal Sen. Photos courtesy: Kunal Sen

Mrinal Sen (May 14, 1923-December 30, 2018), the legendary filmmaker, is credited with taking Bengali parallel cinema on the global stage, like his contemporaries Satyajit Ray and Ritwik Ghatak. His films, like the works of Ray and Ghatak, stood out for their artistic depiction of social reality.

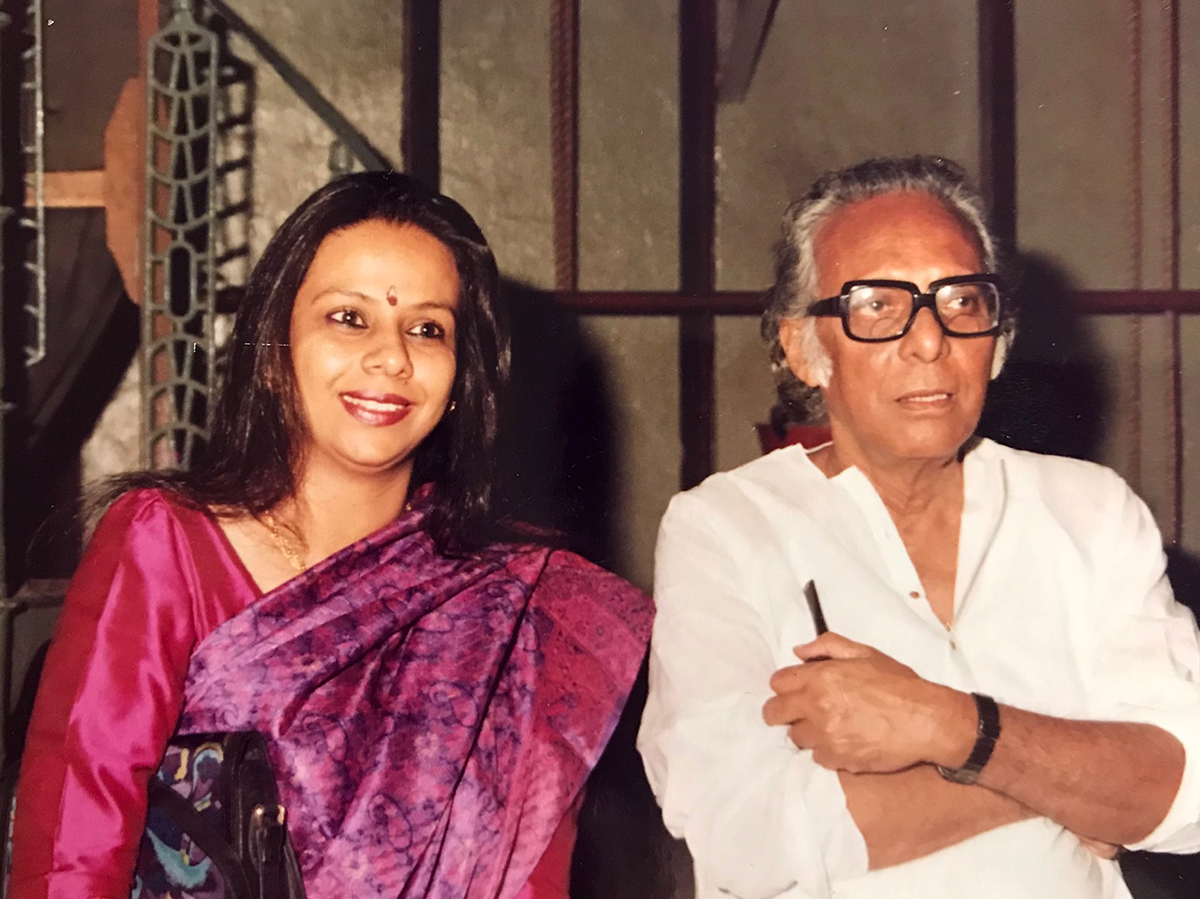

In this exclusive interview, Mrinal Sen’s only son, Kunal Sen, shares some of the abiding memories of his father whom he called ‘Bondhu’, his actress mother Gita Sen, and his growing-up years with them. Excerpts:

INA PURI: Where the oeuvre of his films were concerned, Mrinal Sen’s Khandhar was a rare departure as it probed the complexity of filial relationships. Yet, this was a man who liked to say: ‘I stay away from nostalgia.’ Kunal, drawing upon your own lives, was there ever a moment or mood that became a part of his cinematic narrative?

KUNAL SEN: True, my father explicitly disliked nostalgia and never indulged in it. He liked telling stories about his childhood in Faridpur, but they were not nostalgic tales, and unlike his friend Ritwik Ghatak, he was not significantly affected by the Partition. He came to Calcutta on his own will and accepted it as his home. Personally, I am affected by nostalgia, so I often tried to probe if his apathy for nostalgia was real, or something he consciously decided to practise. We can never be sure, but I think he was truly unsentimental about his past.

However, time, both present and past, had a strong influence on his films. As he often used to say, he was driven by time, and reacted to his socio-political milieu. I think he also had a strong sense of history and tried to see things in the context of history.

When he was still a college student in Calcutta, he witnessed the death of Rabindranath Tagore. Like thousands of others, he went to see his funeral procession. There, in the complete pandemonium of this crowd, he noticed a man trying desperately to take in his arms the dead body of a little child to the crematorium. The crowd just pushed him around. Many years later, he made a film called Baishe Shravan (22nd day of Shravana), the day when Tagore died. In this film that was the day the couple in the film got married. People often wondered why he chose that particular date, and I think it was this memory of his, where, to this one individual, the death of Tagore meant nothing.

In 1977, both my parents went to China for the first time. This was immediately after Mao died. In Beijing they went to see Mao’s mausoleum. There, my father noticed that my mother was crying. She later said she was thinking of the thousands of young men in Calcutta who sacrificed their lives for this man, lying in there. Many years later he made a film called Mahaprithibi where the central question was how easily we can say in hindsight that a political decision was a mistake, and so easily brush aside those who gave their lives. The mother in this film killed herself while Communism in Europe was crumbling. Was she thinking of her youngest son who was killed by the police during the early seventies?

INA PURI: Federico Fellini said: There is a TV set in our flat. It is like an intruder. When I come home I sometimes switch it off…I find it disgusting if my films are interrupted by commercials of spaghetti.' How did Mrinal Sen cope with the assault of popular culture in his domestic space? Or with commercial cinema and bazaar art?

KUNAL SEN: He was no fan of television, and like Fellini, hated when a film was interrupted by commercials. He made a series of 13 short films for television (Kabhi Door, Kabhi Paas), but made the authorities agree to show the films uninterrupted. He believed that the right way to watch a film is in a darkened theatre, where one can temporarily forget about the real world, rather than a television in your living room where one is constantly reminded of the surroundings.

In general, he was just not interested in the popular cinema, and ignored it completely. I heard that my mother had to often whisper in his ears the names of major film stars when they were in some film industry gathering where such stars were present. However, his reaction to this world was that of indifference and not of any type of animosity. In our home the television was sometimes tuned to this type of programming and he would occasionally watch them with amused curiosity, and invariably disturb the ones watching it with inane questions.

INA PURI: In a conversation with Samik Bandopadhyay, Mrinal Sen said; “I have been made in Calcutta. Calcutta has shaped me, inspired me, frustrated me, has made me cry, made me laugh, made me think, provoked me. My contemporary sensibility, that has grown out of my existence in Calcutta, has gone into the making of all my films.” This was when Reinhard Hauff was making a documentary on Sen and exploring his milieu, visiting the village where he had recently filmed Akaler Sandhaney. Did this intimate involvement with a city and its politics change over the years? Did he gradually distance himself and redefine his stance vis-à-vis the Left Establishment?

KUNAL SEN: His attachment to the city was very strong. He loved the idea of urbanity, and Calcutta was the materialization of this idea for him. The city appeared in many of his films, and often they were more than just a backdrop. Yet, he wasn’t interested in the physical details of the city. For example, he would get annoyed if someone pointed out that in his films the characters would sometimes violate the actual layout of the city as they travelled through it. When shooting the city from a higher altitude, like a rooftop, he would try to find a view with the least number of trees. That is not because he disliked trees, but it didn’t visually fit his idea of a city. It is the same way he disliked push-button phones in his films as he visually liked the tension of a finger dialing a rotary-dial phone. When it comes to politics, he was always on the Left, but he preferred to call himself a “private Marxist”. He always questioned the establishment, irrespective of its political color. I remember his first trip abroad was a trip to Soviet Union in 1965, and he came back with a lot of doubts and criticisms, which didn’t go well with many of his leftist friends in Calcutta. He also became critical of the ruling Left party as he felt they were getting complacent and authoritarian. This type of self-criticism was the central thesis of his film Padatik, but he was acutely aware of the thin line between criticism and slander.

INA PURI: Keeping in step with contemporary times, way back in 1986, Mrinal Sen said: “As one living in a world progressing with a rapid growth of science and technology, I find no reason why I should not take to a new form of artistic expression. And, rest assured, I am not going to be a deserter to the cause of cinema.” Tell us about your own work, Kunal, and if this somewhat changed your father's perceptions about science & technology? By 1986, you were already settled in Chicago and your own study and research was distinctly influenced by your own interest in science.

KUNAL SEN: We have had many discussions and arguments regarding the use of high technology in cinema. It started when I was still in Calcutta and then continued over telephone and emails after I moved to Chicago. My father had an allergic dislike to big budget Hollywood-type of cinema. He preferred making films with a very small budget. At times he even negotiated with his financiers to reduce the proposed budget.

This was because he believed that the only way he can retain creative independence is by keeping the budget very low, and thus lowering the level of responsibility and guilt to recover the expenses. He was convinced that anyone making a film with a big budget must compromise.

Since films that employed a lot of high technology necessarily cost more, he was uninterested in that type of cinema and considered them inferior. I, on the other hand, loved technology. I was working on my Ph.D. in Artificial Intelligence, and as a hobby I tinkered with electronics.

My point was that if we set aside the argument about creative freedom and low budget, the newer technologies do allow a filmmaker to do things that were simply not possible otherwise. I often used a Van Gogh sequence in Akira Kurosawa’s film Dream, where he used cutting-edge technology to make his character walk into Van Gogh paintings. My father loved that film, so I argued that this beautiful sequence could not have been made without this technology, and it proves that these technologies are not only to make cheap thrillers, but in the right hand can be used creatively. For example, he was also very skeptical of 3D technologies. I argued that the same kind of resistance was there among many serious filmmakers when sound was introduced, and color film became available.

Most initial uses of these technologies were crude and purely commercial, but some filmmakers found creative uses for them. Therefore, the same should happen with 3D filming. He eventually changed his mind, and at one point he even had a plan to use computer-based animation in one of his films, but that never happened. It still surprises me how he could remain so flexible in his mind till very old age. However, I must admit, we are still waiting for the first creative use of 3D technologies.

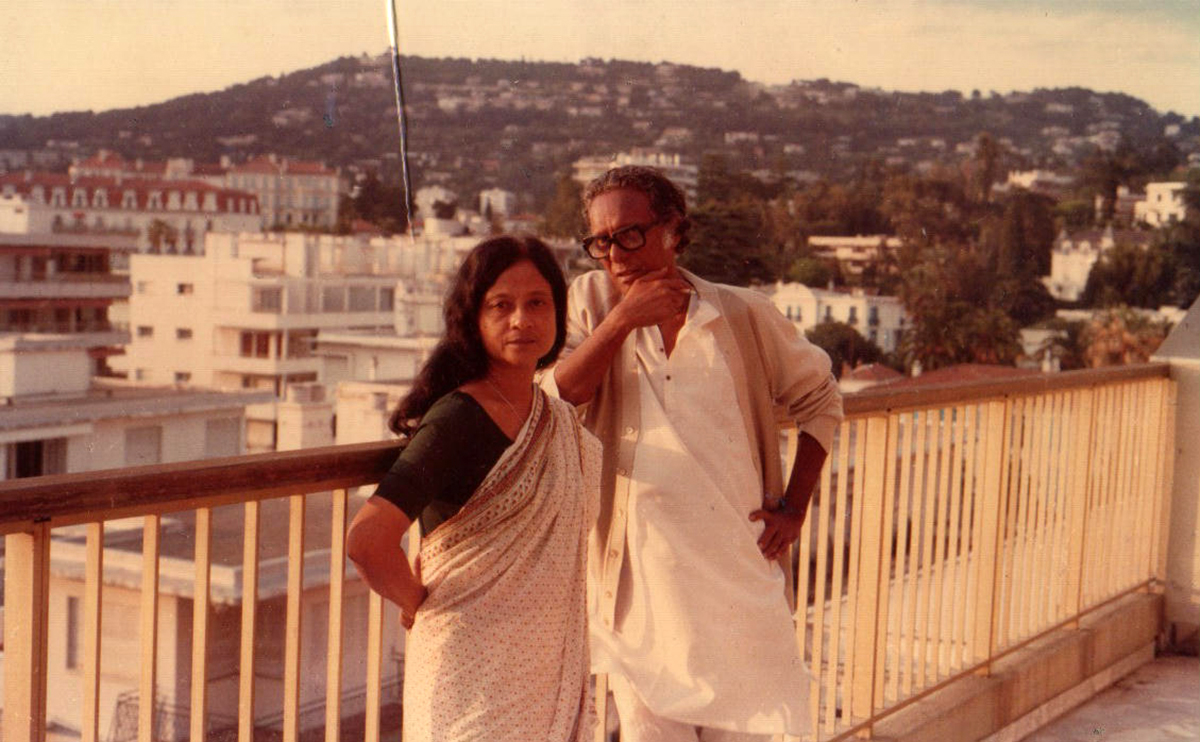

Gita Sen and Mrinal Sen

INA PURI: Going back to your childhood, the household consisted of your parents, your father already a distinguished filmmaker and your mother, Gita Sen, a reputed actress; you also had Anup Kumar, your mother’s cousin living at home. We often had occasions to encounter your family in our school (Patha Bhavan) and elsewhere and often wondered how it was to have a home where no two days would be alike. How different was your childhood, growing up in Calcutta in the late ’50s?

KUNAL SEN: I was extremely fortunate to grow up in a household with so many creative people around me. My father loved his addas, and our living room was always full of his friends, and many of them were incredibly bright and creative people. Until the seventies they were financially very poor, but my uncle, Anu, protected me from feeling the brunt of it. Therefore, I grew up only experiencing the positive side of a creative household, but without the pain of poverty.

My father never tried to mould me in any particular way. I received absolute freedom, and he didn’t even try to indoctrinate me to think independently, which had the strange effect of indirectly teaching me that I have to think for myself. I developed an early pride in thinking differently. Anything anyone said, I had a natural inclination to contradict it. Many people are surprised that I didn't go into films. I don’t know why that is so, apart from the fact that I developed a fascination for science and technology, but it is also possible that subconsciously I wanted to act differently from what everyone outside my household expected me to do.

I don’t know whether my father would have been happier if I went into his profession, but I never ever felt that he was disappointed by what I chose to do. Very recently, when I started making art, he seemed to have liked this trajectory. He probably always knew that I would have had an easier time getting my break if I became a filmmaker, but he trusted my decisions. I remember I hardly used to go to college and spent the entire day at home with my friends. Looking back, perhaps he should have interfered and tried to correct my ways, but he never said anything. I don’t think too many people can claim more freedom to grow.

INA PURI: When we first met at Patha Bhavan, yours being the first batch in the new school that encouraged free thinking and a progressive approach to life, you were just one of the rest. In retrospect, that was the culture the teachers encouraged, if we had well-known luminaries send their children to school, it was with an expectation that they would follow their own paths in life. Sandip Ray was your class fellow, amongst others, and Tapas Sen’s son?

KUNAL SEN: Yes, our school was full of luminary children. Sandip Ray was a year senior to me. Tapas Sen’s son Joy and Amit Ganguly, Kishore Kumar’s son, were in my class. Our class sizes were really tiny those days, with not much more than a dozen students in a class. The atmosphere was spectacularly open and creative. The emphasis was never on formal education, but on being creative. I remember, in our adolescent days, we used to try to impress the girls in our class by creating art on the black board during our breaks.

At the end of the first year of this school, I was in class five, and I stood first in a class of three students. I was a very mediocre student, so I could only achieve this feat in a very small class. The same year Sandip Ray stood first in another class of three or four. On the prize distribution day, Satyajit Ray congratulated my father for my achievement. My father said “first time”. He then reciprocated by congratulating him, to which Mr. Ray replied, “first time”. Incidentally, I don’t think either of us could repeat this performance ever again as the class sizes grew.

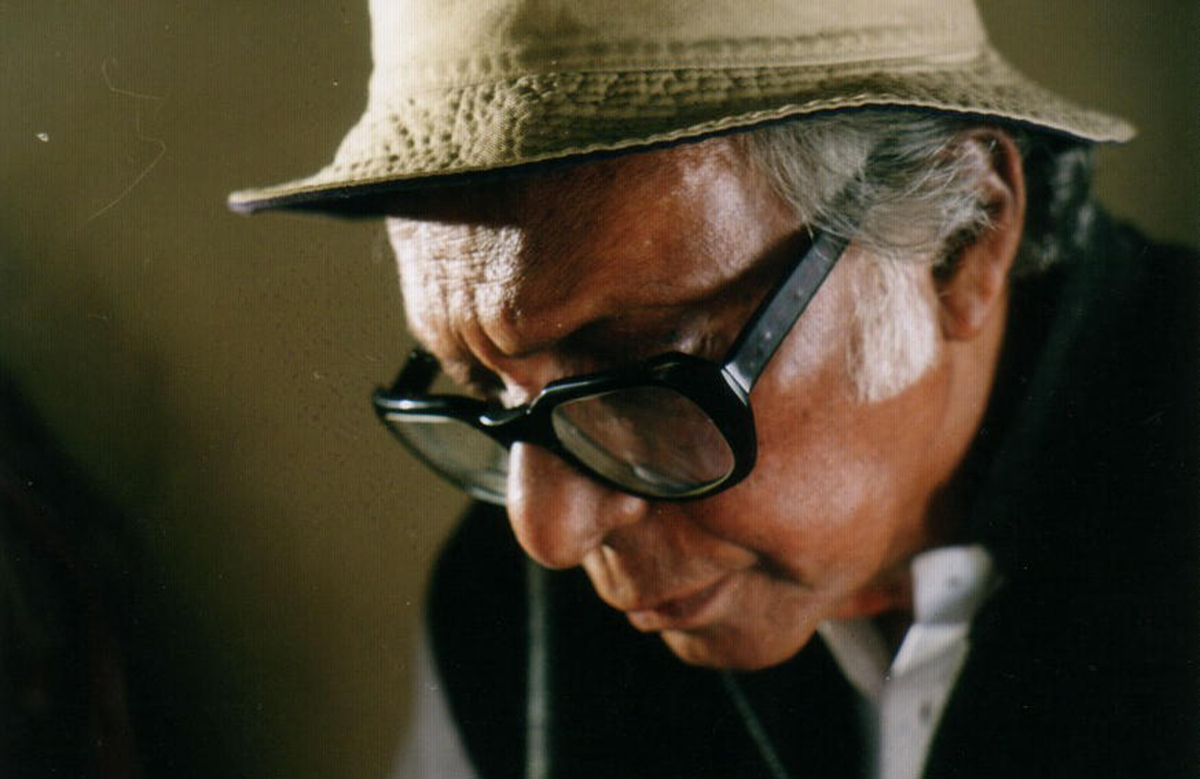

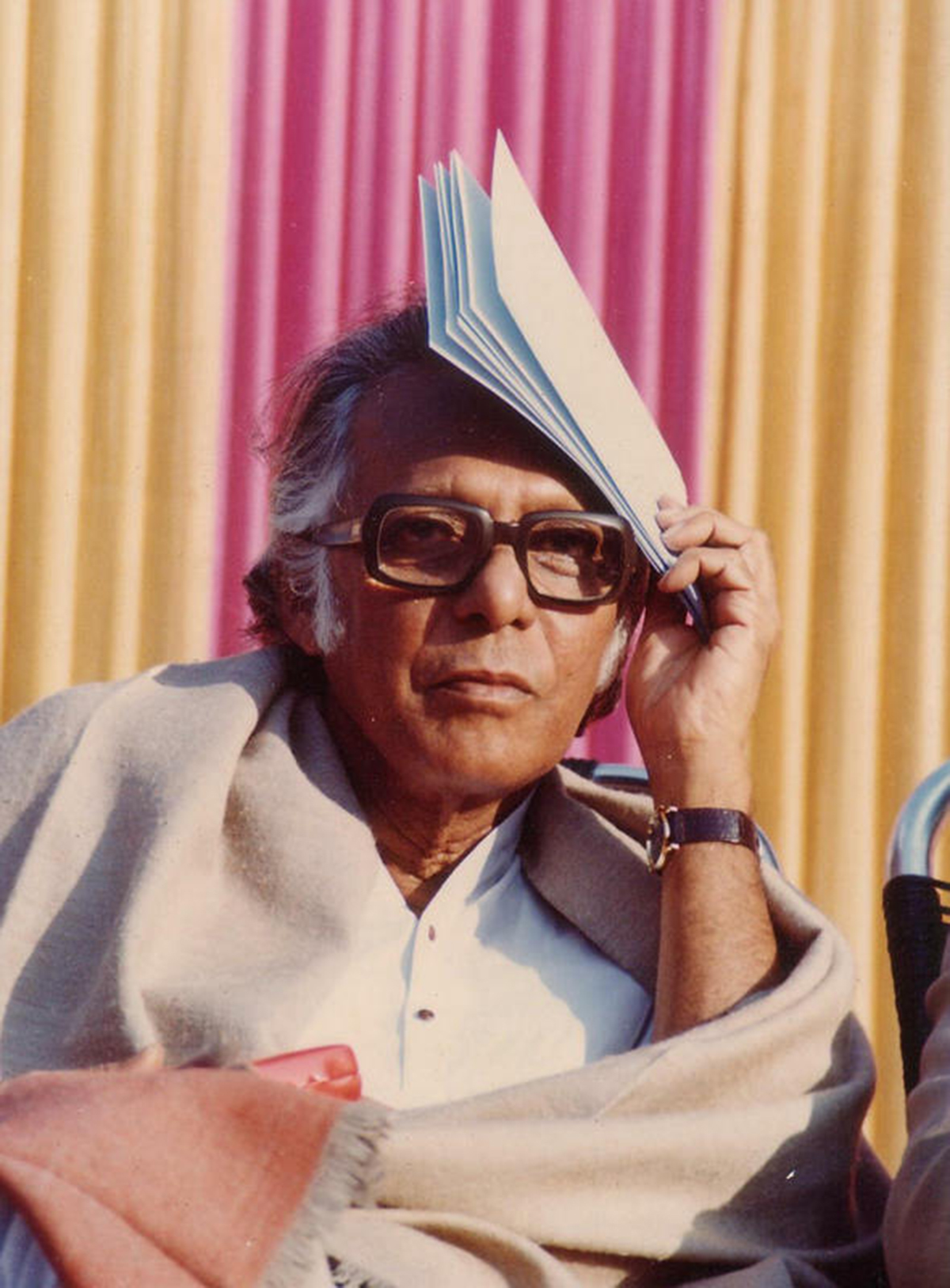

Mrinal Sen and Kunal Sen at Cannes

INA PURI: Share some anecdotes that you recollect about your father whom you called Bondhu.

KUNAL SEN: I called him Bondhu, but he called me Babu. It is interesting that the three contemporaries of my father, my father, Satyajit Ray, and Ritwik Ghatak, each had a single son, and all three of us shared the same nick name — “Babu”. This is perhaps one of the most uninspired and common Bengali nicknames one can imagine. It only shows how much of their respective creative abilities these three fathers were willing to spend on naming their sons.

No one recalls why I called him Bondhu. Some people tried to speculate that this is derived from the last sequence of Apur Sansar where Apu, the father, tells his young son, while carrying him on his shoulder, "we are friends (Bondhu)”. However, this film was made much after I started calling him so.

Now I don’t feel awkward to talk about it, but when I was a child I was deeply ashamed of this fact. I didn’t want any of my friends to discover that I called him Bondhu. Yet, I could not change it to something more acceptable such as “Baba”. One day, when I was around ten years old, one evening my father told me that he would take me and my friends in his rented van to see the immersion of Saraswati idols near the river bank. We were tremendously excited. After the viewing was over, the van took us to a narrow lane next to Metro cinema. There was a row of small eating places and my father fed us kulfi malais. The van was parked a little away from the store, and the food was brought over to us in the van. My father was paying the bills at the store. Suddenly one of my friends wanted to drink water and asked me to arrange it. I was not supposed to get off the van, but being my father, the responsibility was mine and mine alone. This was a huge crisis – how should I call him. I could not shout “Bondhu” as I was afraid of a lifetime of teasing. I simply could not imagine calling him “Baba”. After a lot of thinking I made up my mind and shouted "Mrinal-da”! All my friends today call him “Mrinal-da.”

INA PURI: When we recently gathered to celebrate your father's life after he passed away, at Gorky Sadan, Kolkata, there was no place to stand. Apart from the film actors, actresses and directors, there were many, many technicians, old and fragile who had come from far to pay their last respects, sharing their memories of how generous he was with each and every member of the crew to those who would care to listen. It was heart-warming to hear the tributes, of Tarun Majumdar, Madhabi Mukherjee and so many others. The overwhelming feeling in that auditorium was not of grief but equally of amusement, as colleagues spoke of his humour and sense of fun. Quite befitting for the filmmaker who never compromised till the end and knew how to laugh at himself.

KUNAL SEN: My father repeatedly told me and my mother not to make a spectacle of his death. We tried, as best as we could, to keep it low key. Yet, the absolutely spontaneous reactions were truly heartwarming. It is hard for me to think of him much beyond a father, but when I saw thousands of people reacting with such warmth, sincerity, and love, it made me realize how many lives he had touched. That is why I am trying to remind myself that here is a man who lived a very full life, lived it absolutely on his own terms, was loved and respected by people he never met, and died relatively swiftly – what more can one ask.

That is partly why when they asked me to speak at that event, and I was the first one to speak, I decided to tell funny anecdotes and change the tone of the evening. I really didn’t want everyone to tell the same old thing of what a great man he was and that he will be missed. I think that succeeded to some extent.

Ina Puri with Mrinal Sen

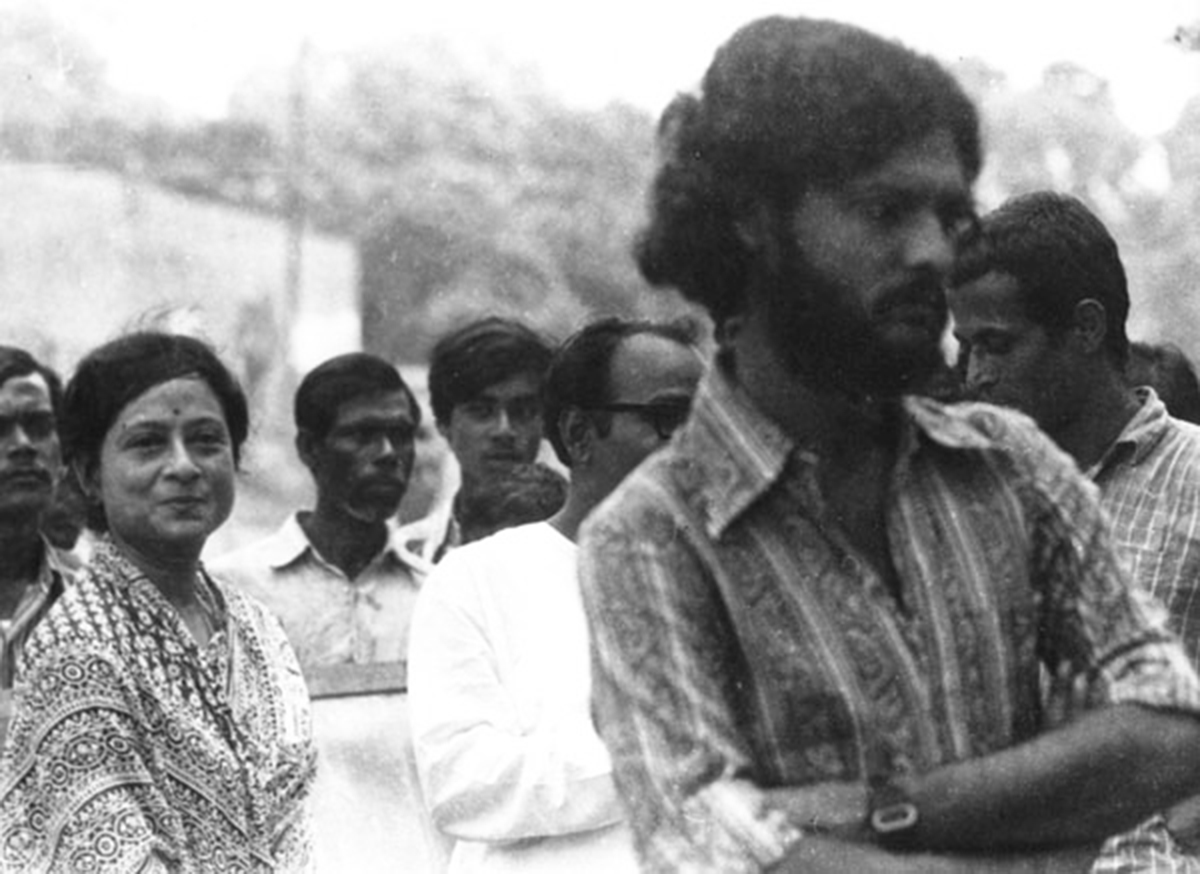

INA PURI: Will you share some memories of Gita Sen, your mother? She was one of the most sensitive actresses of her generation, wasn't she? A woman who could perform as brilliantly alongside Shabana Azmi in Khandahar.

KUNAL SEN: Yes, I think she was a brilliantly sensitive actress. It is one of my deepest regret that she didn’t act more. Every time some other director, outside my father, approached her to act in one of their films, she often agreed in the beginning, and eventually found some excuse to step out. Initially, I believed her excuses, but later I saw the pattern. I never fully understood why she did so, and perhaps she also did not know. I spoke with her many times, and she insisted that the excuses were real. Apart from Shyam Benegal, she had the opportunity to work with Aparna Sen, Gautam Ghosh, Rituparna Ghosh etc., but she ultimately dropped them. Once Satyajit Ray, after watching one of her films, commented to a friend that she is “Mrinal’s asset”. I think that is true in many ways, and not just in her acting.

My mother grew up under extreme hardship. Her father was involved with the freedom movement and was jailed. He was released when he was already terminally ill, and as was customary, the British administration did not want to have a political prisoner die in jail under their watch, he was released at the age of thirty-three. He died a few months later, leaving behind his young wife and three children, where my mother was the eldest. Since then she had to play the role of the head of her household and the primary bread winner, but as a young teenager what she could do was very limited, and the family was constantly at the border line of starvation. She had to depend on her relatives for support, and since they themselves were of very limited means, it was a hard and humiliating life. Her marriage to my father did not ease the situation as he too did not have any income.

As a child I spent most of my time with my mother, and she used to tell me stories when she thought I was too young to understand. She told stories of pain and suffering, of nobility and sacrifice, of loss and survival. She told stories of her childhood in a small town by the river. I believe we are all made of stories, and my morality and my soul were formed out of these stories.

INA PURI: Would you please touch upon the films that left lasting impressions on you? Were you privy to the ideas, storyboards before he filmed them? Did he discuss his script with you or consult with you on anything related to his films?

KUNAL SEN: Since I was about fifteen, I was taken in as a full member of our household. I had an equal voice in everything — both mundane household decisions, as well as creative choices. At that time, in my adolescent self-confidence, I thought that was normal, and that I deserved it. Now, looking back, I realize how unusual it was, and how lucky I was to deserve that respect.

Since then, my father would always discuss his every idea with me and. my mother. This was partly because the rest of the people surrounding him were rarely critical, but he knew we would be brutal. Of course, he would try to defend his ideas against our criticism, but he must have seen some value in it, as his decisions would sometimes get modified after our discussions. My mother was very instrumental in changing his dialogs. As an actress, she could easily see what words can come more naturally to a character. My criticisms and suggestions were more structural and conceptual. I don’t think they were particularly meaningful when I was just a teenager, but over time I must have matured a little, and the films he made between the mid-seventies to the mid-eighties perhaps had more of my influence.

After we moved to Chicago towards the end of 1983 this interaction had to reduce. Phone calls were terribly expensive those days, and therefore were limited to enquiries of our mutual well-being. Form then, until email became popular, we had a gap when I could not get involved in his creative world. I regret that because I believe I could have had a positive influence in some of the films he made after Khandhar. In the post-email era, we once again started communicating, but by then he was mostly done with filmmaking. We worked together in the books he wrote after that. He would email me each chapter, and I would send back my feedback, and they went back and forth. During this period, he sent a couple of script ideas, but these were never converted into films.

Regarding my favourite films, I loved and still love Bhuvan Shome for its innovative freshness. I think Padatik remains a great example of deep political analysis in an Indian film. I loved Ekdin Pratidin and Kharij for their brutal portrayal of what it means to be middleclass. Khandhar is one of my most favorite films. One film that is little discussed, Chalchitra, I think is exceptionally modern in its content and style. I think the audience is still not ready to accept such a non-narrative and non-emotional style, but I hope someday the film will be better evaluated.

Gita Sen with Kunal Sen

INA PURI: The other day we met at your place, the producer of Kharij spoke of restoring the older prints and hoped most of the films would be available for a Retrospective. While this will be time consuming, do you have any plans of organising a Retrospective in the future?

KUNAL SEN: I would love to see such a thing being organized in India and elsewhere. I have already heard of several such attempts, both in India and in Europe and US. However, doing a complete retrospective would be very hard to put together. Many of his films are lost forever. The ones that survived are often not in very good shape. The National Film Archive in Pune has digitized or restored copies of many of his films, but to get them out is not always very easy. Then there are subtitling issues, as some of the films they have in the archive are either not subtitled or subtitled in languages other than English. The other huge problem is that of rights ownership. My father was not the rights owner of most of his films, but unlike Kharij, where the owner is still traceable, for 90% of his films the owners cannot be traced down easily. However, if someone wants to screen these films in a larger venue then they will need the permission of the rights owner in writing. Once an international film restoration organization wanted to restore a couple of his films, but they would not proceed until they could get legal permission from the rights owner, which we could not obtain.

While I would love to see retrospectives where the younger generations can get to see his films on a big screen, I am too far away, and I am too busy with my day-to-day life to be able to organize something like that. Of course, I would help in any way I can, but I cannot be the prime mover. It will take a lot of effort, and a lot of running around that I cannot do from this far away.

INA PURI: Please share memories of the time you and Nisha went with Mrinalbabu to Cannes in the not so recent past.

KUNAL SEN: That was in 2010, when Cannes decided to show Khandhar in their Cannes Classic section. This is a very prestigious venue, and that year the other directors who were also honoured included Jean Renoir, Luis Bunuel, Luchino Visconti, Volker Schlondroff, John Huston, Alfred Hitchcock etc. My father always had a deep love for Cannes and had attended it many times either with his films or as a member of the jury. I could see that he was really eager to go there one last time. However, his health was declining, and my mother was too ill to be his companion. She did not want him to go alone, so Nisha and I convinced her that we will be with him throughout. Nisha had played chaperon before in other festivals, but I never travelled with him beyond my teenage years.

The two of us reached Frankfurt a day early and received him at the airport. After that we spent a couple of days in Frankfurt to get him comfortable and then flew over to Cannes. His long time European agent and a very close friend, Eliane Stutterheim, was there to receive us. That evening some of us met for a beautiful dinner. It was his 87th birthday. They reminisced many previous birthdays they celebrated in Cannes with a lot more fanfare and fireworks, since Cannes always overlaps with his birthdays. It was a wonderful evening.

The screening was also very heartwarming. We didn’t expect a big crowd since people generally prefer watching new films that are being shown. However, we were pleasantly surprised to see a very full auditorium and a standing ovation.

This was also a moment of a sad realization for me. The person I always knew as a great storyteller, who could hold an audience as long as he wanted to, had lost his ability to think on his feet. During interviews, his answers were far less engaging. He could not process complex questions easily and answered with what was already percolating through his mind, rather than answering the actual question. The brutality of age was apparent, and he realized it too.

However, in spite of that, he was very happy to be there one more time and proudly shared with us all the old memories — where he met whom, what they talked about. He was missing Ma, who was always there with him during past visits. After five days we came back to Frankfurt, and after a day of rest we put him on a return flight. That was the last time he travelled anywhere. The last seven years of his life he never left home. Age is a terrible thing.

INA PURI: Mrinal Sen leaves behind an invaluable arc

Donate Now

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated