The Khushwant Singh Literary Festival (KSLF) was started in 2012 at Kasauli (Himachal Pradesh) to commemorate noted author and journalist Khushwant Singh, who had penned several books at his summer house here. The idea behind the festival was to promote Singh’s legacy by discussing the values he stood for, and addressing his concerns, including closer ties between India and Pakistan; equal opportunities for the girl-child and women; and disseminating the values of democracy, tolerance, compassion in a world that is increasingly more polarised. Six years after the KSLF took wing at Kasauli, it travelled to London at a pop-up event in 2018.

On June 26 and 27, KSLF London, held virtually from London, hammered home the message, ‘No Man is an Island’. The first digital edition took off with an underlying message of cross-culture relations that form the bulwark of our society. The two-day litfest saw historian Fakir Aijazuddin dwell on the ideas and philosophy of Khushwant Singh, whom he described as a quintessential humanist who epitomised different religious persuasions. Other sessions included: Vidya Dahejia in conversation with William Dalrymple about her book, A Rediscovery of India in 100 Objects; Victoria Schofield talking at length about her book, The Fragrance of Tears, based on the life and experiences of former Pakistan prime minister Benazir Bhutto, in conversation with Javed Jabbar; and British-Indian author Shaheen Chishti, a descendant of the famous Ajmer Sharif dargah family, about his book, The Granddaughter Project, in conversation with actor Divya Dutta; actor Kabir Bedi in conversation with Sarah Jacob about his book, Across the Universe; and Dr Jane Goodall talking to Gargi Rawat about her forthcoming book, The Book of Hope.

Rahul Singh (extreme right) with delegates at a previous edition of the Khushwant Singh Literature Festival. Photo: KSLF

Even though KSLF is organised entirely by volunteers, Khushwant Singh’s son, Rahul Singh, and his partner, Niloufer Bilimoria, who is the director of the festival, have been the moving spirits behind it. Robin Gupta, author and poet and former IAS officer, who retired as Financial Commissioner Revenue, talks to Rahul Singh and Niloufer Bilimoria about the festival and Khushwant’s Singh enduring legacy.

Rahul Singh

Rahul Singh has been a writer, journalist and editor of Reader’s Digest, The Indian Express, Sunday Observer. He has penned, among other books, an engaging biography of his father Khushwant Singh, In The Name of the Father (2004), which was launched by Amitabh Bachchan. He is an advisor to World Literacy Canada, President of Satyagyan Foundation, India, President of the media awards committee at the Population Institute Washington.

Rahul studied in about 11 schools as his father was posted all over during his years in the Foreign Service. It was at an Elysee in Paris that he picked up his French. He graduated in History from King’s College, Cambridge.

Excerpts from an interview:

Robin Gupta: Rahul, with the world at your feet and your high academic qualifications, why did you choose to be a journalist at a time when journalism was not much of a sought-after profession? You could as well as have been a barrister ending up on the bench of the Supreme court, a diplomat at the Court of St James or for that matter, a Union Minister, given your endearing persona, high qualifications and vast network of friends and high connections. Did you have a choice in the matter or, did you, in natural reflex, follow in your renowned father’s footsteps?

Rahul Singh: Yes, I got a very good degree in history honours at Cambridge University. My father at first thought I should get into one of the big multinational corporates as they paid well. I was interviewed by Shell, ICI (Imperial Chemical Industries), the Tatas, Hindustan Lever and Duncan Brothers, among others. They all offered me a job but my heart was not into boxwallah life. Being in the Foreign Service was also an option, but again, I did not think it would suit me. Having been brought up with books and feeling idealistic, I felt journalism was where I should go. Actually, I became a journalist before my father did. The Times of India was looking for journalists at a senior level who would be trained. So, I became a trainee assistant editor. Two others joined likewise, both graduates of Oxford University.

After one year of reporting and the news desk, we were made to write editorial and opinion pieces. My first major reporting assignment was covering the opinion poll in Goa in 1967. I had to sign a five-year bond with the TOI and as it so happened, just when the bond was coming to an end, I learnt that the Reader’s Digest was looking for an editor to run their Indian edition. I applied and was selected. That was when I was just 28 years old. I spent a year of training in the British Reader’s Digest in London and then returned to Bombay to take up my assignment.

I was with the Digest for 11 years and I also set up its first Hindi edition, Sarvottam. Sadly, that was not a financial success and had to close down after a few years. Then, in 1981, I ran into Ramnath Goenka and he took a fancy to me. They were looking for an editor for their flagship Bombay edition. The chief editor of IE was George Varghese, under whom I had worked in TOI. He interviewed me over the phone and offered me the Bombay editor job. He was the best editor I have ever worked under.

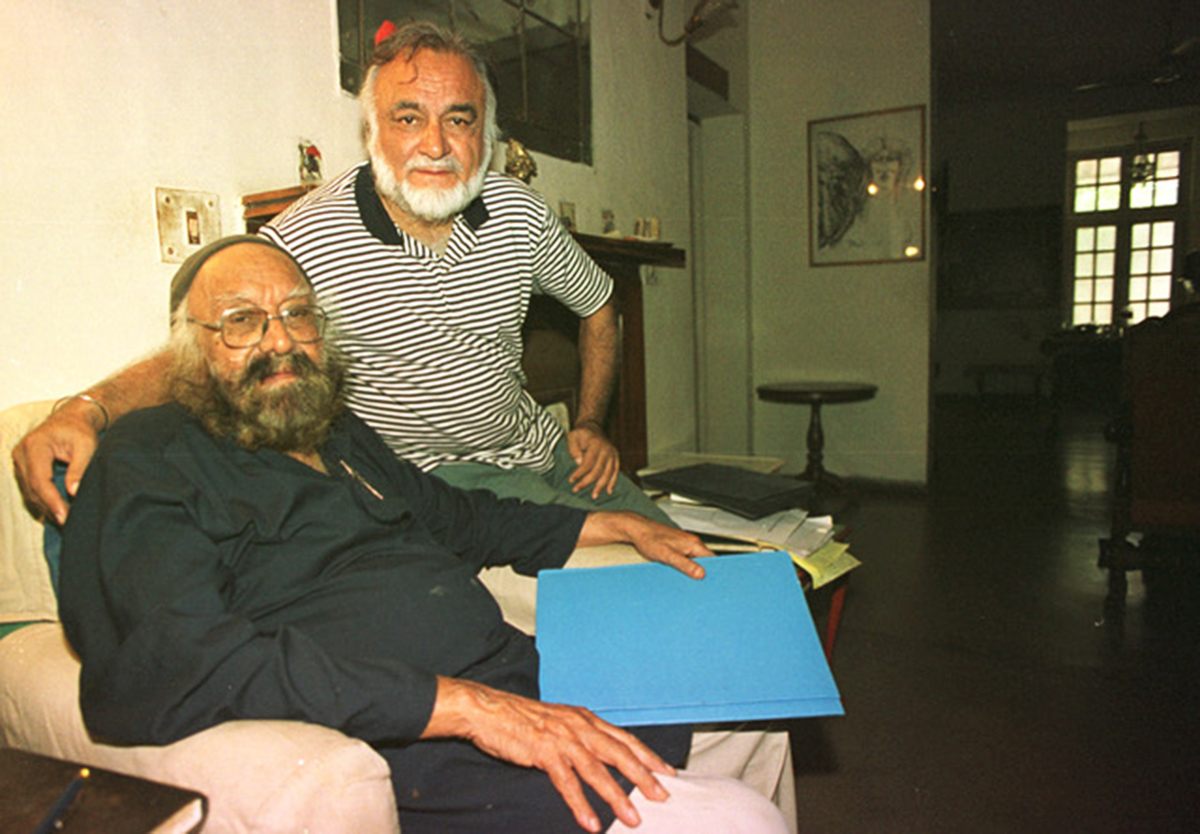

Khushwant Singh with Rahul Singh. Photos: Mustafa Qureshi

From Bombay, I moved to Chandigarh as editor, straight after Operation Blue Star when Sikh militancy was at its worst. I spent three years there and then Vijaypat Singhania, who was starting the first computerised paper in India — The Indian Post, with Nihal Singh as editor — asked me if I would join as his number two in Bombay. So, I moved back to Bombay, but The Indian Post did not last long. Nihal Singh and Singhania fell out. I was made the acting editor and Vinod Mehta was offered the editorship, while I was offered his job as editor of Sunday Observer.

I was with the Observer for three years, until the Ambanis bought it over form its owner and made him an offer he could not refuse. Luckily, I had some close contacts with the United Nations. They were looking for a writer to do a book on the population issue. I gave them a proposal since population had been one of the subjects I had specialised in. The proposal was accepted and I became a consultant for the UN to write the book, which took me two years during which I travelled to eight countries in Asia, Africa and Latin America that had been successful in their family planning programmes. It was the most rewarding three years of my writing career.

I freelanced after that and then out of the blue, I got an offer to become the editor of Khaleej Times in Dubai. The previous editor, Nihal Singh, my boss in The Indian Post, had recommended my name. But it was really not my cup of tea as there was no freedom of the press in Dubai. But I lasted out one year, made quite a bit of money, which I had not made earlier. The stock market was booming when I returned to India, so I invested my savings in the share market and the returns have sustained me since then. I should add that the Reader’s Digest virtually gifted me a flat in Bombay since I had made so much money for them. That, in brief, is my journalism career.

Robin Gupta: If I may hazard a guess, could it be that you were a curious person by nature, interested in the strange, unpredictable and the unexpected nature of human beings whom you generally confronted and this is what attracted you to journalism as a career? Have you ever regretted being a journalist.

Rahul Singh: I was attracted to journalism mainly because of my love of writing and books and though it may sound pompous, to serve the country and make it a better and more just society. I also loved interacting with people and travelling. My most rewarding periods were my stints in Chandigarh at the height of the militancy, and also writing the population book. Never regretted being a journalist, but I do feel that nowadays, many journalists and editors have compromised themselves. It takes a lot of guts to oppose the establishment. But Goenka and the editors who worked for him did so under Indira Gandhi’s Emergency rule. They should do so now, with all this love jihad nonsense going and hard Hindutva targeting Muslims.

Rahul Singh with actor Shabana Azmi at a previous edition of the KSLF. Photo: KSLF

Robin Gupta: Would you agree that the fourth estate has a stellar role in preserving democracy and freedom? Please recount some important incidents when writers, by bringing hard, objective facts to the notice of the public, helped in tiding over a repressive situation or played an important part in changing world history.

Rahul Singh: Journalists in both the print and electronic media must stand up against the powers that be and be true to their profession, even if it means persecution and loss of job. In Pakistan, many journalists have criticised the government and the Army and paid for it with their lives. In the USA, the Watergate expose by Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein removed then President Richard Nixon from office. The Tehelka sting operation exposed corruption in the defence ministry and led to the resignation of the then BJP president Bangaru Laxman and also George Fernandes. But the government went after Tehelka and its promoters in almost unjust fashion; journalists must be prepared to face that.

Robin Gupta: Would you agree with a widely believed viewpoint that the BJP, supported by the RSS and the government of Narendra Modi, have divided the country into two well-demarcated compartments in which 80% of the Hindu population, or thereabouts, calls the shots? Could this lead to more partitions of India?

Today, on the one hand, we have the face of a pious ascetic committed totally to the economic development of India. It is understood that old age pensions have increased, and each village house now has electricity, water connections and bathrooms. His having started work on the Ram temple and removing Article 370 from the Constitution as well his seemingly successful foreign policy with India’s neighbours get him great laurels and approval of the majority community. On the other hand, we find India veering towards the edge of an economic precipice, the sky-high inflation having ground even the middle classes into despair and the entire Muslim community fuming and up in arms at Mr Modi’s anti- Muslim postulates and initiatives. You will agree with Rahul that a country can only develop as a whole? Are the Muslims deliberately being left out of the scope of development? Has Mr Modi deliberately destroyed the pluralistic, liberal tradition of a secular India?

Rahul Singh: All I can say is that I blame the Congress leadership, and, in particular, Sonia and Rahul Gandhi. It is abundantly clear that they are no match to him when it comes to drawing crowds and mesmerizing the masses. Somehow, the people have faith in him and he is able to put a spin on even the most disastrous of moves, like the demonetisation and implementation of the GST. He has handled the farmers’ agitation badly and on love jihad, he has kept quiet. Trouble is that the people are largely behind him. They have faith in him, which is going to be difficult to shatter.

However, the Nehruvian ideals essentially form the idea of India. These are secularism, and an inclusive society, and going by the Constitution, the judiciary and the media must act as checks on the executive and, when needed, oppose it. Sadly, this is not happening. But I am hopeful. We Indians are a hard-working, decent and tolerant people. But we need better leadership. It need not come from the Congress. It can come from elsewhere. I was very hopeful about Arvind Kejriwal, though he ultimately disappointed, but we need more leaders like him.

Niloufer Bilimoria

Niloufer Bilimoria conceptualised the KSLF and is grateful to then Brigadier and now General Anath Peruvemba for giving it life. The fest, an annual event, is spread across the second weekend of October in Kasauli and now in summer in London, too. At other times, she is absorbed in yoga and Vedanta. And feeding stray dogs in the garden by the sea near her home. In her working avatar, she was PR Manager at Oberoi Hotels and General Manager International at The Times Group.

Excerpts from an interview:

Niloufer Bilimoria with actor Sharmila Tagore at a previous edition of KSLF. Photo; KSLF

Robin Gupta: Niloufer, let me start by congratulating you and Rahul for progressively accelerating the literary movement in India by starting a literary festival in the name of Khushwant Singh, thereby perpetuating the legend that was his alone in his beloved retreat at Kasauli. Through your visionary efforts and sustained commitment, the KSLF is now well institutionalised. It has also gained the well-earned reputation under your direction of being the best organised literary festival in India.It is generally perceived that the calibre of participants in the different panels and the wide audience who attend the festival from all parts of India and abroad at Kasauli has left India’s intelligentsia wondering at the excellent curating, crafting and arrangements for such a large gathering of deeply interested persons who go up to Kasauli to attend the festival year after year to listen to India’s best minds and interact with them socially.

Niloufer Bilimoria: These days if someone pays a compliment I begin to feel like a medical miracle of some kind, to paraphrase Shobhaa De. I guess doing a festival these days is a medical miracle.

And we just cannot take any credit greater than anyone else in the team. In fact, I am the most dispensable team member right now. Everyone else does the work. And there would be no fest without them. Ashwani Kumar is our tech whiz kid aided by Rahul Gauba in Chandigarh; our social media enthusiasts and fanatics are led by Harinder Singh and Kirandeep Kaur of 1469, Oona van den Berg in UK, and Bharat Avalani in Malaysia. Media champs are Kishie Singh and Ajay Bhardwaj in Chandigarh. With Ajay Bhatia our passionate photographer.

Our board members, Mr Purshottam Dhir and Varun Kathuria, are completely hands-on and responsible for setting up the Trust that runs the festival; they also handle all our accounts, tax and stuff we have no clue on! Our other board members have partnered us through from the day we began in October 2012. Mrs Charanjeet Singh has been such a dear friend to Khushwant Singh, and now to the festival bearing his name — Khushwant Singh Literary Festival. Ashok Chopra has been an integral part of the team since inception. He held our hands from day 1, and we all worked closely together on both the event and the curation, along with Anand Sethiand SuneetVir Singh.

The festival has grown organically. Today our volunteers are banded together by Ashima Bath, who steps in as compere when needed, and is so dedicated that till date she has not seen a single festival though she is a much-loved and revered teacher of literature at the famed Sanawar school. Lila Kutty, whose husband was KS’s favourite doctor, and ours too, runs the “Joy of Learning” program with school children. Recently she roped in young Rachna Bisht Rawat as well. The residents of Kasauli are a huge support, hosting so many of our events and people. Wish we could name them all here. But we can send them our big love. KSLF is a purely voluntary effort. Our team are all busy working people who find the time to do this. None of them take a penny from us. And they are working from morning to night during, before and after the festival. Every fest is an eternal work in progress, moving from utter chaos and confusion to more chaos, innumerable glitches, a grand finale, and then the cleaning up which never ends.

Our partners and friends who support us year after year include the media, our speakers and authors. They are all an integral part of KSLF. People like Himachal Tourism, Yusuf and Farida Hamied Foundation, the amazing people who brought down the price of AIDS drugs for the third world; Biostadt, Kuantum Papers, Meridien Hotels, Sun Foundation, Sahitya Akademi, Vitabiotics, and so many more.

We must tell you of the most important person behind the festival, without whom there would not have been any fest. Brigadier Ananth Narayan and his lovely wife Aparna. I casually bounced the idea off him one evening at the Kasauli Club. He immediately jumped at it and ensured we had a fest just three months later! I don’t know of anyone who has started a new project in just three months. Brigadier Ananth has. Our abiding faith in the army continues to get reinforced each year. And our gratitude goes out to him and all the Kasauli Brigadiers thereafter. And to the executive committee of the fabled Kasauli Club.

The Army has been a huge support for us each year. Our generous and amazing Brigadiers are among the finest men you could not find anywhere! Hopefully, one day we will be able to work with a lady Brigadier, too. We would not be able to hold the festival without them. Big, big thanks.

In 2020, too, Brigadier Naveen Mahajan was kind enough to invite us to Kasauli for a socially-distanced fest. We reluctantly declined as we did not want to transport the virus from Bombay (which was very bad at the time) to pristine Kasauli.

Dolly Thakore, Divya Dutta, Shobhaa De and Vikram Seth at a previous edition of KSLF. Photo: KSLF

Robin Gupta: As director of the festival, the credit goes to you in the greater part. Kindly tell us of your inspiration behind this festival and how you visualised it from the start.

Niloufer Bilimoria: KS never wanted anything named after him. The idea behind the Khushwant Singh (KS) literary festival was to bring alive diverse subjects that were of interest to him, to Kasauli and the areas around it. These include its fragile ecology, rich heritage, colonial history, and ever present military that has helped preserve one of India’s tiny hill stations. KS was 97 years when the fest began. With a dream. That this meeting of minds can celebrate the power of ideas that can transform our lives by raising awareness for causes of interest to KS, ranging from ecology to women’s roles in society to Indo-Pak friendship. He has written the authoritative history of the Sikhs and is an agnostic who knows more about religion that many of the clergy!

We have also dedicated the fest to the young Indian soldier. To give them opportunities to read and grow and explore their passions as KS has done. Why Kasauli? Kasauli has been the summer home for this noted writer for over half a century. It is here in Raj Villa that he wrote several of his newspaper columns syndicated across some twenty publications all over India, translated into seventeen Indian languages,as well as a hundred and fifty novels, including works of non-fiction.

Profits from the KS literary trust are ploughed back into preservation of Kasauli and its environs.And into education of the girl child.

When I first visited Kasauli, I wanted to know where Ruskin Bond was born. No one in Kasauli could tell me. Finally, I asked KS. Military Hospital, Kasauli, pat came the reply. And I thought, here is a tiny place no one has heard of. It has produced such fine literary talent. KS wrote many of his books at his family home there. We want the festival to reflect his values and interests, and carry forward a sense of history, which is lacking in India.

We began modestly with a couple of hundred people. Today, it is filled to capacity and overflowing. The economy of Kasauli has boomed and Kasauli now has a place on the world map. The New York Times mentioned it when they wrote about our festival.

What the many, many admirers of Khushwant Singh find fascinating is the continuity in his legacy through this festival. One of Khushwant Singh’s greatest contributions to the world of literature was that he groomed up some of the best young Indian writers in the English language. Namita Gokhale, a protégé of KS, as indeed Sheela Reddy, have made waves. Namita is the director of the internationally renowned Jaipur Literature Festival while Sheela’s book, Mr and Mrs Jinnah, which initially had the blessings and support of KS, has become a bestseller and is being turned into a film for which Sheela has sold the copyright. This is Khushwant Singh’s legacy. It is such an uplifting feeling to find authors groomed by KS spreading literature throughout the world.

Yes, almost every journalist of a generation acknowledges KS as their mentor. In addition to the names above, Bachi Karkaria, MJ Akbar, Fareed Zakaria, and many more. Happily, almost all have spoken at KSLF in Kasauli. Including people like Vikram Seth who were extremely close to him. Fareed recalled at the last fest that he was in tears saying goodbye to KS at the Victoria Terminus railway platform in Bombay. Vikram has a cherished memento from his library in Kasauli.

Robin Gupta: What is your magic formula for ensuring excellence in every aspect of the arrangements?Are you very strict in making choices? Are you totally uncompromising with the average?

Niloufer Bilimoria: You are too kind. Every fest has its share of glitches and disasters. Ask any litfest organiser! Here, too, we have a wonderful team of professionals who manage the event. But our volunteers are hands-on, working closely with them, backing them up every step of the way. In our quest for excellence, I am the Nazi in the scene! We try and put the personal chaap KS so that each one to has a memorable experience. This is what we strive for. And it is our team led by Amit Sood that actually does it.

Robin Gupta: We understand that the KS Litfest has started in London as well. Will this be a recurring annual event once the Covid-19 nightmare becomes history?Do you plan to hold the festival in other parts of Europe in the Coming years?

Niloufer Bilimoria: We are not an event management company. And so will not take the festival elsewhere. Both Kasauli and London have KS connections, so to speak.

Kasauli is where KS did a great deal of his writing. Contrary to what people think of him, he was an extremely disciplined man. He woke at 4 am and by 7 am, his column was neatly written out in his beautiful hand, ready to be posted to his secretary for transcription on the typewriter. He had also read all his newspapers and magazines for the day. About seven papers at least.

London is interesting. Then High Commissioner Navtej Sarna invited us to London much earlier. And is responsible for planting this seed. Zed Cama and Mayfair Hotels made it all happen for us. London is where KS studied and worked. And, therefore, it is a city that he loved, a city that shaped so many of his interests and values. His interest in nature began in London, when he would take the daughter of an English family friend for walks. And she would ask him questions on the birds and trees. He even wrote Nature Watch which today is Trees of Delhi. So, our first festival had the support of the High Commission. At that festival, we were approached by King’s College London, KS’s alma mater, to have the fest at their campus. The subsequent festival was held there. All of this is very closely connected with KS. KS also worked at the Indian High Commission in London after Indian Independence. And, thus London became the new dot on the KSLF map.

Robin Gupta: Since the Kasauli festival is so widely supported by the glitterati of India, is there a problem in raising finances to run the festival on such a scale? Do you have a trust and a corpus which services the festival?

Niloufer Bilimoria: Regarding the dreaded finances,you said it! Rahul raises almost all the funds, mainly via friends of KS and friends of KSLF. People in Kasauli are the most generous in the world. And we are blessed to know them and count them among our friends. The smallest donation is often the most precious, given with so much care and love. But a fest cannot survive on love alone.

We really need corporates to back us consistently. KSLF is a meeting of minds to bring alive the power of ideas that can transform our lives. We are dedicated to causes that are close to KS:the education of the girl child as well as ecology of the region. We are a not-for-profit. Every penny donated is ploughed back into the festival. We do not take a Rupee for travel or stay or administration.

The Khushwant Singh Foundation runs the festival. All donations get a tax exemption under 80G. We are a litfest with values that work towards these causes. A worthy trust for any corporate with values to be associated with. We do hope your magazine can reach out to them. They can reach us through our website, kslitfest.com.

We also appeal to the friends of KS and friends of Kasauli to leave KSLF a legacy that will ensure its continuity and help create a corpus. In a year without funds (2020), we still managed some wonderful speakers at KSLF, including Pico Iyer, our keynote speaker, Sudha Murty, Amitav Ghosh, Shobhaa De and many more. The festival also organised Fareed Zakaria’s India book launch.

Robin Gupta: Would you agree that the KSLF is the only one of its kind in the sense that it is meant to promote literature and literary genius; not to project personalities or management committees?

Niloufer Bilimoria: We are really not aware of what other festivals do.We are, to the best of our knowledge, the first, and perhaps the only one in India, to be named after a person. I remember facing a lot of flak over this, but time has shown it was the right decision.

We are also the first to dedicate ourselves to causes that are dear to KS. The “Joy of Learning” is a wonderful programme, where we have had 10,000 children across Himachal participate, thanks to the government of Himachal. We also give scholarships to girl children, and donate books to a poor school in a tiny village outside Kasauli. Each year, we have had sessions focused on ecology and women’s issues. We have contributed to water harvesting in the area. We need more volunteers to help us grow these programs. It is a legacy we want to leave in Himachal.

Every festival is based on a theme relevant to the day. Last year, the theme was something we all want, A New Life. Sessions were carefully crafted and curated around these themes. Perhaps this is how we also differ from many others.

And, of course, we are perhaps the only volunteer-driven festival in the country, maybe the world.

Robin Gupta: How is it that the KSLF has not widened its scope to include drama, dance and the performing arts, exhibitions of paintings?

Actor Manisha Koirala at a previous edition of KSLF. Photo: KSLF

Niloufer Bilimoria: Oh! we would love to do so much more! We all love the arts and literature. We have some wonderful music sessions, Indian and Western, both in the mornings and evenings. At the end of a day of intense listening, people want to let their hair down and relax with music and dancing and food. A unique aspect of KSLF is our very dedicated audience who are with us all throughout the day. We have held art exhibitions too on subjects of relevance to the themes.

Robin Gupta: As you are aware, India is going through stressful times as far as intellectual freedom and free expression are concerned.Also, there is a marked bias, we feel, against the minority community, the Muslim community in particular. In fact, we understand that guests to the Kasauli festival from Pakistan were denied visas to attend literary discussions. What is your attitude and Rahul’s view in this regard?

Recently, there has been a great push towards promoting Hindi and Sanskrit at these festivals. However, the intelligentsia in India conduct business in the English language in the belief that English is an Indian language. May I have your comments in this regard?

Finally, may I voice a resounding proposition that a statue of KS be put up in the Ratendon Road roundabout or at the entrance of Delhi in the Mandi House Traffic Island. Will it be in order for the next festival to pass a resolution to this effect so that a proposal is in the pipeline and can be auctioned at the appropriate time? After all, a great city is known by its great writers and artists and KS was the best-known writer of his times, who loved Delhi more than any other city.

Niloufer Bilimoria: KS was a great believer in Indo-Pak friendship. For it is only through communication that we build ties. In the first few years, we had the largest Pakistani contingent compared to any festival in the country. (I don’t know about JLF. They are in an international league apart from any other litfest). All the Pakistanis who attended were friends of India and spoke very movingly on India. Once visas were withdrawn, we had to “uninvite” the Pakistani guests.

Of course,English is an Indian language. Can you name one government official whose children do not go to an English-medium school if they can afford it? Because all jobs today depend on our ability to speak, read and write English. In an interconnected world, no man is an island. We must be practical.

Having said this, on a personal note, I must add that I am a student of Vedanta. I recite and study the Gita in Sanskrit, then understand it in English. My teacher, incidentally, has a doctorate in English. If she had not studied English, I and hundreds of others with her would not have been exposed to such an amazing heritage of ours. Rahul’s niece teaches history at St Stephen’s College, Delhi, and her speciality is the period of the Ramayana and Mahabharata. She cannot do this without her knowledge of Sanskrit. And she cannot convey this legacy to her students without her knowledge of English. So, we are all for India’s heritage as well as English. The finer nuances of Iyengar yoga, an ancient Indian art and science, are explained to me in English. We have had people like Arshia Sattar, an authority on the Ramayana, speak at KSLF. We have covered yoga too. But English, and not Sanskrit or Hindi, is our forte. And we stick to our core competencies. However, many of our sessions are multilingual,with plenty of Hindi and Punjabi. The day we have more lay people speak Sanskrit, we will include that too.

It is really very kind of you to suggest a statue of KS. KS, however, never ever wanted anything in his name. Postage stamps have been suggested in the past. He did not have a choice as far as the festival went!We bullied him into it! What he would like us to propagate are the values he lived by and his works. He wrote the most definitive history of the Sikhs during his Fulbright fellowship, which remains unsurpassed to this date. He believed in Indo-Pak friendship; he believed in equal opportunities for women; he believed in nourishing and cherishing the only planet we have.

We would like to encourage Indians writing in English because English is our forte. And KS encouraged generations of young journalists and writers as mentioned earlier.

His favourite poems were Leigh Hunt’s ‘Abou Ben Adhem’ and Kipling’s ‘If’. Anyone reading this must read these poems to understand his tremendous sense of ethics and values. I would call him a Hermit disguised as a Hooch. He never propagated his finest qualities. He concocted a string of debauchery around him, all completely fictitious. He had a delightful sense of mischievous humour. When the film star Nargis wanted to stay at his Kasauli home he agreed on condition he could tell people, “Nargis slept in my bed”! The fact is he was Saint or Sant Khushwant. He would hate this prefix, too! Finally, a work of art needs a muse. At KSLF, our eternal muse is KS.

(This interview was updated in July)