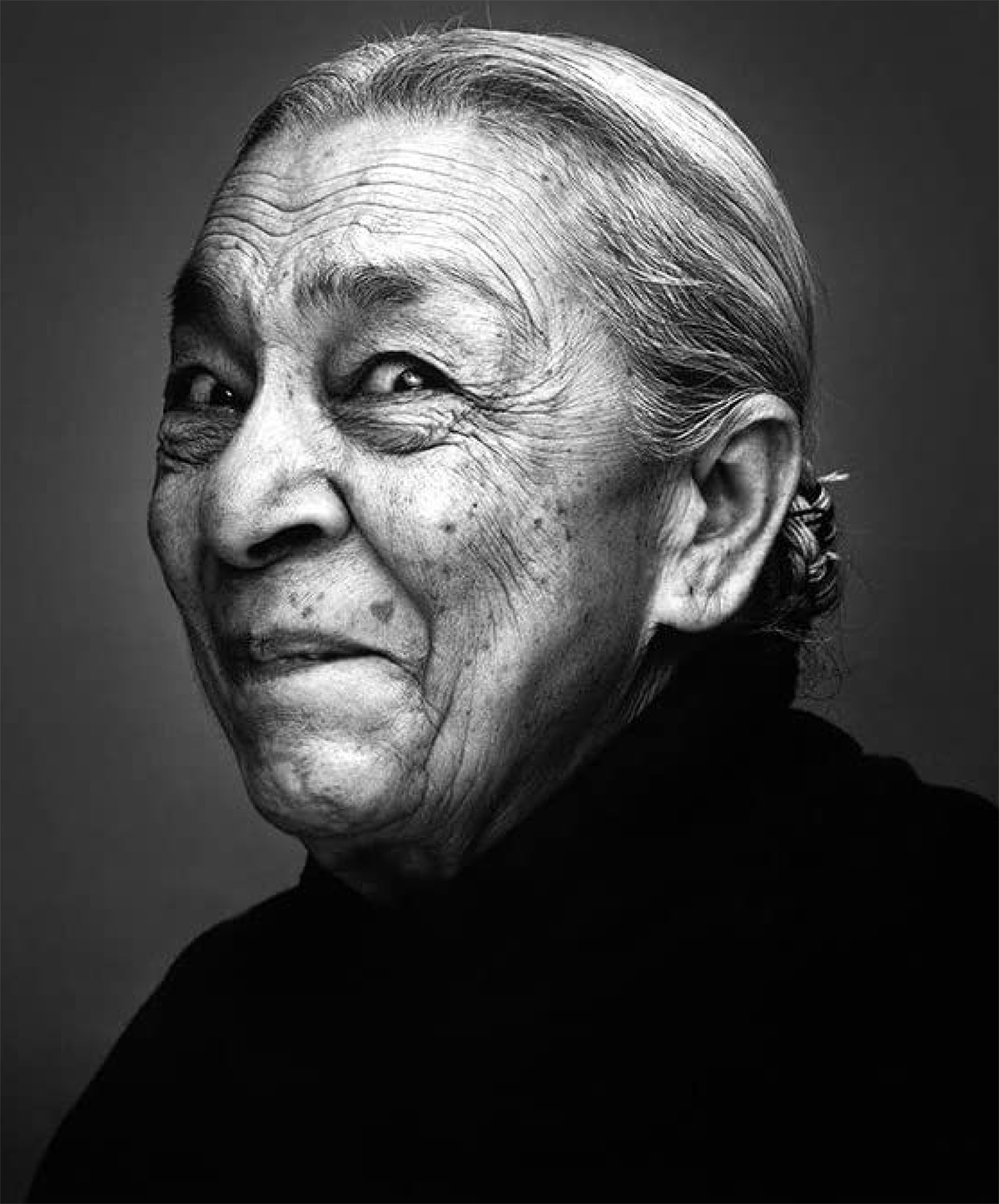

Author and publisher Ritu Menon. Photo: Jonathan Page

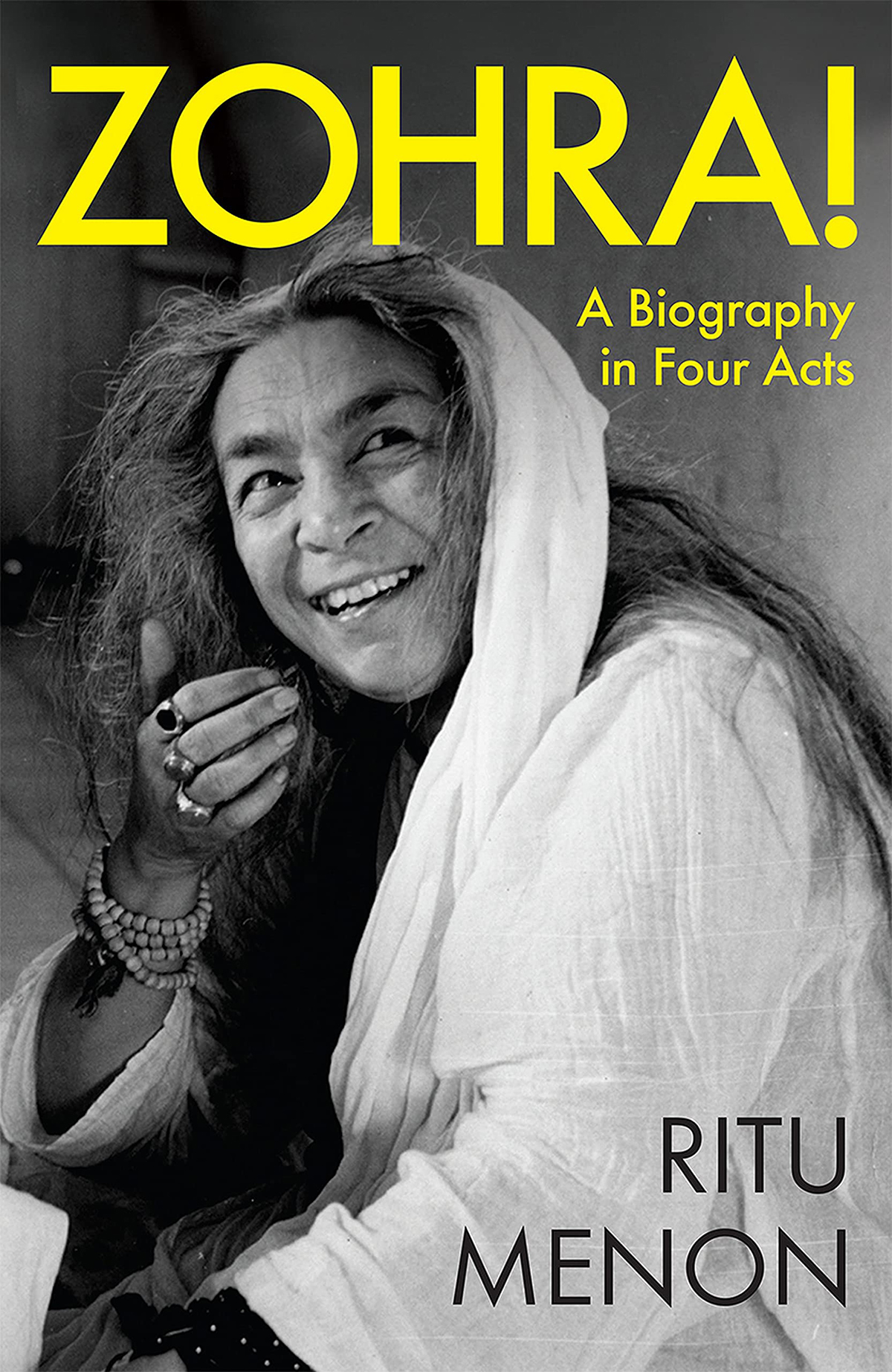

Author and feminist publishing icon Ritu Menon’s engaging and immersive biography of actor Zohra Segal, Zohra! A Biography in Four Acts (Speaking Tiger Books), is set against the sweeping changes in arts, both in India and abroad, spanning nearly eight decades. Reading it will make you see an era lost in time unfold before your eyes, giving you a ringside view of the life and times of the grand old lady of Indian cinema. It opens with twenty-three-year-old Zohra Mumtaz, born into a privileged family of Rampur in 1912, receiving a telegram from the legendary figure of Indian dance Uday Shankar in 1935, asking her to join him on a tour of Japan. What follows is the whirlwind of a life in arts. Earlier, in 1931, Zohra had made an overland trip to Dresden to study eurhythmics at the Mary Wigman School. Shankar taught her to work with the body as a whole.

Menon’s biography, written from the vantage point of someone who knew her subject closely, is suffused with rich details involving the important milestones in Zohra’s life as well as the significant figures in arts who were instrumental in her evolution as an artiste. When she was seven, Zohra was sent to a purdah school for young girls from aristocratic families — Queen Mary’s College — which was founded in 1908 in Lahore, along with one of her sisters, Hajrah. She was a boarder there till her matriculation in 1929. Menon tells us that Zohra’s natural tendency to independence and boundless curiosity was nurtured here. “It was Queen Mary’s that gave me a career,” Zohra once said. “How would I have thought of it otherwise? I was good at two things—dancing and acting ... I didn’t want money: I was interested in fame, I wanted power.”

The ten years of imbibing a liberal, broad-based secular education at Queen Mary’s, writes Menon, made a lasting impression on Zohra, socialising her into developing skills that would stand in her in good stead later: “Naturally gregarious — and despite calling herself an ‘anglicised snob’— she learnt to swim with the tide, to get along.”

Structured in four acts containing two scenes each, and with two intermissions, the book chronicles Zohra’s romance with dance under Uday Shankar; her 14 years with Prithviraj Kapoor and his touring company, Prithvi Theatres, a leading repertory for Hindi theatre in India till the curtain came down on it in 1959; her remaking of herself as a single mother after her husband’s suicide; her life in London; her ascent to stardom; her years as Bollywood’s favourite grandmother and her demise in 2014, followed by an analysis of her life and work.

Excerpts from an interview with Ritu Menon:

Nawaid Anjum: Zohra! A Biography in Four Acts locates her life and work in the backdrop of the history of arts in India spanning a century. Since she was someone who happened to cross her path with the right set of people at the right place and at the right time, both in India and abroad, do you think the life she made of herself was fortuitous, shaped by the circumstances she found herself in?

Ritu Menon: Well, in a way most remarkable lives are fortuitous in some respects, aren’t they? Individuals seize the moment, use the opportunities that come their way, and chart their course either skilfully, or not. In the way that I have chosen to present Zohra’s life, perhaps the only decision she made that was independent of her circumstances was that of pursuing her first love, dance. Nothing in her life up to that point could have influenced it, it was pure impulse. And unconventional, to boot — who would have thought that an aristocratic young woman would opt to do something like that? So that, and the equally important decision not to get married, as most other young women of her generation and background would have done.

As to fortuitous — yes, a certain conjunction of circumstances did open up particular options for her. If the Partition hadn’t happened, she might well have established an important dance school in Lahore. If she and Kameshwar hadn’t relocated to Bombay, she might never have joined Prithvi Theatres and become an actress. And if Kameshwar hadn’t committed suicide, she might not have moved to England and made a career for herself there. These would be the what-ifs of her life, just like anyone else’s, and her life might well have taken a very different turn.

But the question that I would have liked to ask her, had she been alive when I was working on the book, would be: what really made her decide to stay on in England, given her age, and how hard her life there was, and for such a long time. Remember, success came to her only in her late 60s-early 70s.

Nawaid Anjum: Yes, indeed, and yet, as you mention, it would be wrong to conclude that everything she achieved as an artiste across various disciplines was circumstantial as she forged her own path at every juncture, making the most of whatever opportunities came her way. Since she was a single mother after her husband's suicide, and the sole breadwinner of the family for most of her life, was her decision to become a part of the projects that came to her governed as much by her artistic impulse as the need to eke out a living? How do you look at her approach to her craft?

Ritu Menon: What is remarkable about Zohra is that once she had made a decision, chosen a particular path, she gave it her best and most. As long as she was with Uday Shankar and Prithviraj Kapoor she was one among many others, dancers and actors, all of whom were part of an ensemble led by two charismatic, brilliant, larger-than-life figures. They led, and the others followed, albeit contributing creatively to the final product.

In my opinion, it was actually only in England, where she was virtually on her own, with no towering figure to depend on for her artistic expression, that she came into her own. It was in England that she forged her own very distinctive style, made her roles memorable, and established herself as a skilled and dependable actor. It was where her true mettle was tested, and proved to be more than up to the task.

Zohra! A Biography in Four Acts

By Ritu Menon

Speaking Tiger Books

pp. 272, Rs 599

Nawaid Anjum: The Women Unlimited published Zohra’s no-holds-barred autobiography, Close-Up, in 2010. Earlier, in 1996, Kali for Women published Stages: The Art and Adventures of Zohra Segal, written by Joan Erdman and Zohra Segal, which you have mentioned in this book, too. Kiran’s Zohra Segal ‘Fatty’, the tribute to her mother on her 100th birthday, was published by Niyogi Books in 2012. What new grounds did you want this book to cover?

Ritu Menon: A memoir (Close-Up) or an autobiography (Stages) is a very different thing from a biography, though we often think of them as interchangeable. Put very simply, it’s the difference between first-person and third-person, between direct and reported speech. It’s also a question of perspective. Zohra’s life spanned a century of tumultuous events in India, politically as well as culturally and artistically. I wanted to consider her in that context, to highlight her life and work against that backdrop. To understand her, if you like. Then, she happened to be in England in the 1960s, she arrived there just as there was an explosion of creative energy in theatre, music — I mean, the Beatles had just erupted — film and television, and I thought that should also be part of her story. The beginning of multicultural programming for a second generation South Asian audience, and so on. You won’t find this either in Close-Up or Stages, because that was not part of Zohra’s account of her life. Then, I wanted to speak to people she worked with, colleagues, directors, actors, to get a critical appreciation of her from her peers. To weave these many strands into a tapestry that presents this variety and richness.

Nawaid Anjum: Did you consciously stay away from dwelling on the interiority and the constitution of her mind, choosing instead to tell her story through the choices she made? You have spoken about how you wanted it to be a feminist biography. Did it entail focusing on particular aspects of her life and work or some specific traits of her personality?

Ritu Menon: There were so many times during the research that I wished I could have talked to her, asked her what only she could have told me — or not, which itself would have been revealing — that only she could have clarified. Intimate questions like: how did she deal with Kameshwar’s suicide, what really did it do to her, emotionally? Did she honestly never look back without regret, as she said to me more than once? Who did she confide in? And so on, so many aspects of her life that remain enigmatic. But not being able to ask her, I didn’t want to speculate. That is a very feminist decision, to consciously avoid superimposing ones own “take” on what we cannot know.

The other is to focus on what it means for a woman to decide how to live her life — in Zohra’s case, to pursue her career even when she was aware of what was happening to her husband and to her marriage, and to continue doing so. Then, to dislocate her children and relocate them to another country because of the choices she had made. Not too many women do this, and certainly very few among her generation could or did. After all, her own beloved sister, Uzra, gave up her career when she moved to Pakistan, and so could Zohra have, after Kameshwar died. She didn’t. On the contrary, at the age of 50 she decides to uproot herself and try her luck in another country, in a brutally competitive field, with neither looks nor a godfather to shepherd her through. My endeavour was to consider her life and choices from this perspective. I may not have succeeded, but I tried!

Nawaid Anjum: Zohra wrote in her biography that the secret to her fortitude and determination was “an inner spring, a bubbling font of joy that surmounts all tragedies, however heartrending”. You knew her well through the decades. What according to you are the strengths of her character that kept her in good stead much of her life? How would she look back at her life and the decisions she had made in her conversations with you? Did the fact that you knew her well made writing this book easier?

Ritu Menon: An iron discipline, rather than an inner spring — although I’m sure there was that, too — is what I think saw her through hard times and tragedy. That, and a resolute will. I can’t really say I knew her “well”, even though I knew her for quite a long time. So there were some aspects of her personality that I had first-hand experience of, and some confidences, but if I had had an opportunity to discuss say, her frank assessment of herself as an actor, or why she felt she had to continue acting till her late 1990s, it might have given me an insight into her character, that I can only surmise. So there is that absence in the book...

Nawaid Anjum: The book is strewn with interesting nuggets around arts, from the history of theatre in India to the emergence of crossover programmes on TV and in cinema in the UK. Did you set out to weave in the context for the readers today, many of whom may not be aware of the fact that Zohra was a pioneer when it came to featuring in such cross-cultural ventures?

Ritu Menon: Yes, very consciously. We are so impressed when we read about Bollywood actors today “breaking” into Hollywood or minor television serials, but Zohra was acting with the likes of Richard Gere, Yul Brynner, Michael Caine, Dame Peggy Ashcroft, Rita Tushingham, Art Malik, and many others, fifty years ago! We forget that Madhur and Saeed Jaffrey, and Roshan Seth and Zia Mohiudeen, among others, were acting with the greats long before today’s crop of actors, and in far more challenging circumstances.

Nawaid Anjum: How did her relationship with the four men in her life shape her as an artiste; her favourite Uncle Memphis with whom she travelled by road from Dehradun to Luxor, Egypt; Uday Shankar whom she joined on a tour of Japan in 1935 as a 23-year-old, and later, elsewhere in the West; Prithviraj Kapoor, whose Prithvi Theatres she did several plays with; and Kameshwar, eight years her junior, whom she married at the age of 30, breaking her vow never to get married?

Ritu Menon: Zohra dedicated her memoir & autobiography to these four men, so all were clearly very important in her life. Memphis was an early confidant, she was close to him, as I have written, and he supported her in her unconventional choices. That was a very important factor in her being able to develop her talent as a dancer, to take a chance, as it were. I can’t think of too many parents or relatives in India who would have encouraged a 19-year-old girl to study dance in a foreign country, where she knew neither the language nor anyone she could call a family friend or acquaintance. No instant communication, no cell phones or Internet or WhatsApp. Imagine the courage that took, both hers and her father’s, and Memphis’s.

Obviously, Uday Shankar and Prithviraj Kapoor were major influences in her artistic development, in very different ways. She understood, and was struck by, the power of innovation in Uday Shankar’s dance practice, and by Prithviraj’s passionate espousal of theatre as a transformative, social and collective art, and vocation. And it was political, though Zohra herself was not political in that sense. What she saw in Prithviraj and tried to practice herself, was an egalitarianism in her interactions with her colleagues and peers, as well as with her juniors.

But I also think that she was greatly influenced by the professionalism she found in British theatre and film (the lack of which she deplored in Indian theatre and film), and that stayed with her throughout her acting career. You must remember that Prithviraj never trained anyone, actively avoided it, so what Zohra learnt at the British Drama League and later, with directors and other actors, was invaluable.

Comments

*Comments will be moderated