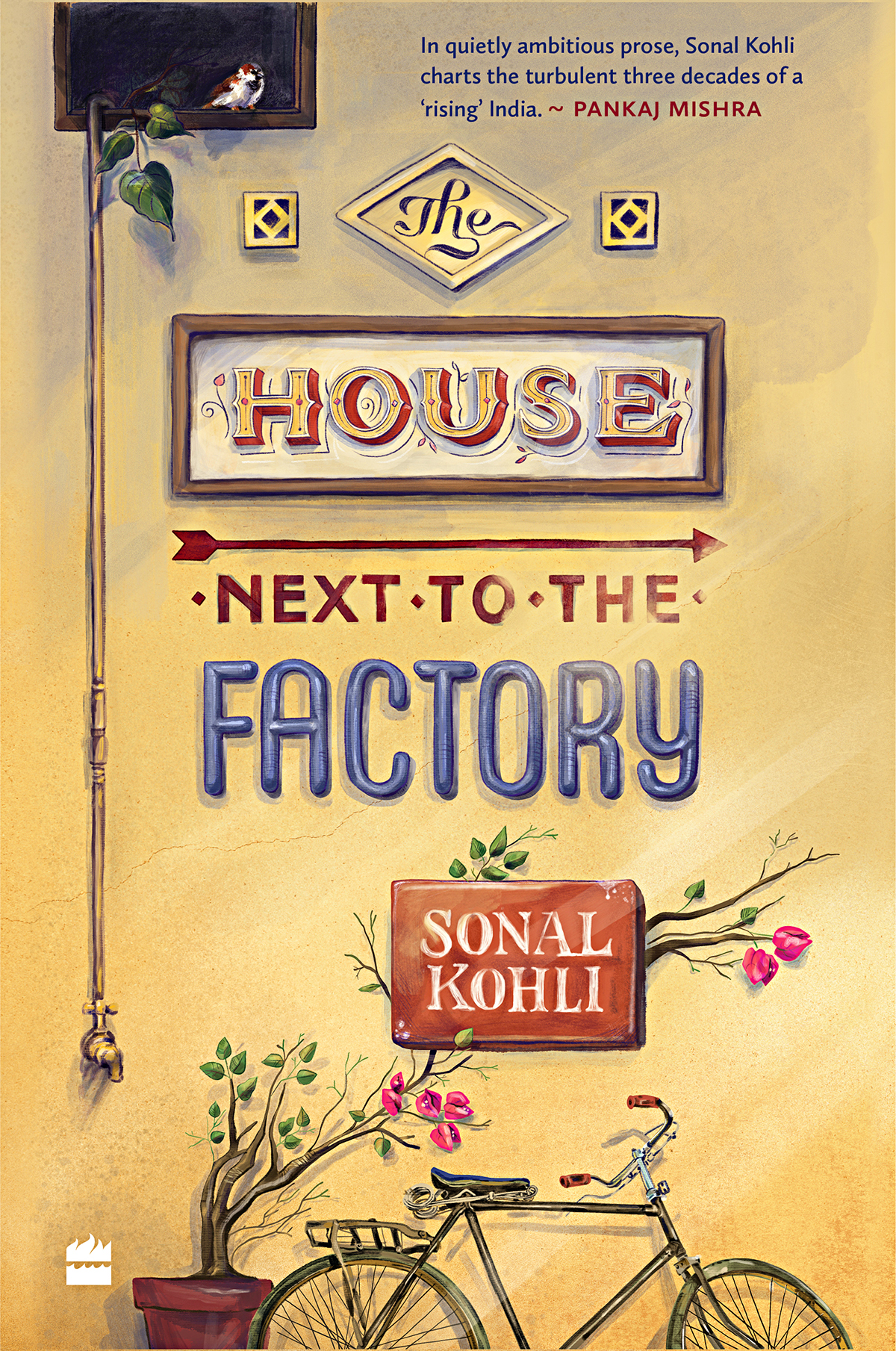

Sonal Kohli, author of The House Next To The Factory. Photo courtesy: HarperCollins India

‘Indian Writing in English opened a whole new world to me, a world that was strikingly familiar and thus alluring’

In her debut collection of intricately wrought short stories, The House Next to the Factory (HarperCollins India), Sonal Kohli introduces us to intriguing and extraordinary characters, but paints them with the hues of the ordinary, making them strangely familiar to us. “Our imperfections, I believe, make us real, genuine, lovable even. As much as possible, I wanted the characters in the book to be real, humane, imperfect,” Kohli, who grew up in Delhi and now lives in Washington, D.C., says. The nine stories in the collection are about the quiet lives of people; each of them strikes us with its distinct beauty. Kohli says that writing for her has been the most rewarding journey. The stories she narrates are unique probably because they are distilled from her own observations and life experiences.

Excerpts from an interview:

At the outset, tell us about your passion for writing. How did it begin?

I never hoped, imagined or dreamed of being a writer. Reading was always a hobby, and I remember summer holidays spent with books — Malory Towers was a favourite series. In high school, I binged exclusively on Danielle Steel and Sydney Sheldon. It was only in my twenties that I picked up Thackeray, Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, Tagore. Out of nowhere, I chanced upon a list of Indian Writing in English, and it opened a whole new world to me, a world that was strikingly familiar and thus alluring. I judiciously bought and read every book on the list. These stories were close to home; they were about characters like me and around me. Here the food, the seasons, the cadence of the language, the sweltering heat, the endless monsoon, everything was familiar. I related with Indian literature like I hadn’t with books before. I read copiously for six years. Without realizing it, I began knitting stories in my head. Soon, I was writing.

You have a unique way of engaging the readers. How did you work on crafting the plot and settling on the narrative — was it deliberate or spontaneous?

I’ll say that it was both deliberate and spontaneous. With each story, I had some sense of the ‘plot’ — though, in my case, it would be more accurate to call it ‘narrative flow’ — I knew the setting, had an inkling of its mood. I began working on each piece with this tenuous knowledge. Once I started to put things down on paper, little by little, I let go of trying to make the story fit my idea of it. Instead, I followed the story’s rhythm, its own instinct. I let the story guide me. I became first an observer, someone watching the narrative unfold, and only then its writer. Almost every time, the story turned out differently from what I had envisaged — parts of it fell away, certain scenes became redundant, new characters pressed their way in, the ending changed.

Though they are a work of imagination, in what ways do you see these stories connected with real lives and situations?

All the stories are fictional, but they are inspired from things I’ve seen, observed or come across. I find a shade of myself in all the characters that I write, be it the two brothers from “Steel Brothers” or the servant or the sweeper from “Other Side of Town”. I guess lending something of my own to these characters is my way of breathing life into them.

Be it the tutor from “One Hour, Three Times a Week” or Kavya from “The Outing,” they are characters woven from the life around us, but their stories are enticing, with a cloud of mystery surrounding them. You seem to have paid much attention to bringing out the extraordinary in ordinary characters.

When I wrote these characters, I didn’t think of them as either ordinary or extraordinary. I thought the characters felt that they were at the centre of their own personal universe and their respective stories were important to them. They wished (and deserved) that I pay close attention to their lives, their emotions, their yearnings. I, on my part, simply let them be what they wanted to be on paper.

I also felt that the stories have a common theme of the past that lingers in the minds of the characters. This is something that knits the events of the past and the present in the narrative. Was it a theme that you set out with?

I didn’t set out with this theme in mind, but yes, the characters are preoccupied with their pasts. As human beings, we keep moving back and forth in time in our minds. It’s not how it should be, but we rarely stay only in the present. I like to mirror this movement in my stories. I feel it creates texture as well as narrative energy and keeps the story flowing. A story might be set on a single day or an evening, but we come out with a deeper understanding of the characters than what’s afforded by a short encounter.

One of my favourite stories was "The Outing". It was an amazing experience to saunter through various streets, to the memory lanes of the character, gradually shifting my own identity to that of the character, and finally experiencing the joy of meeting Sister Celina. The story brings forth a very different tone by making the readers a part of it. How did you plan this?

The Outing is the shortest story in the book, yet it took me a long time to write it. In the initial draft, the story was in third person, past tense. Here, Kavya and two of her school friends set out on a rickshaw from Kavya’s house in search of Sister Celina. But the voice in this draft didn’t feel right. In the subsequent version, I let go of one of the girls and now it was Kavya and one friend making the journey. Because of the urgency of their search, in this draft I changed the tense to the present. But the voice was still not coming through. Finally, I let go of this friend too; I figured the outing was a personal pilgrimage for Kavya and the friends didn’t have anything at stake in the search. I shifted to first person, present tense. But something was still off. Kavya didn’t seem ready to make the journey all by herself. Finally, I tried the second person narration, bringing in the reader and letting him/her stand in Kavya’s stead. Immediately, I found the voice of the story. The narrative started to flow. Everything clicked and fell into place.

The House Next To The Factory

By Sonal Kohli

HarperCollins India (Fourth Estate)

pp. 196, Rs 499

Would you talk about the settings you chose and how you crafted the characters accordingly?

Most times the setting and the character are tied together and they come to me in the same instance. For example, in “Weekend in Landour”, I had a vision of Abhay at the hill station, picking out a book at a bookstore, and the story flowed from this image. Sometimes, however, things are not so easy. I know I want to tell the story of a certain character but I’m unable to find the narrative for it. Often things get rolling only when I discover the right secondary character; the protagonist’s story then glances off the back of this character. It happened with Other Side of Town, where I knew this was Johnny Walker’s story but I didn’t know how to tell it until Rani showed up. The same happened with Kettle on the Hob.

The themes are subtle. They touch upon little emotions, human imperfections and the slight and blatant moments that are imbued with a meaning of their own. They all appeared genuine to me. Did you want to convey a particular message through them?

Our imperfections, I believe, make us real, genuine, lovable even. As much as possible, I wanted the characters in the book to be real, humane, imperfect. But, no, I didn’t have a message to convey through them. Because reading is a leisurely activity, a hobby for many, if anything, I strove for the stories to be immersive, readable, entertaining, rather than moralizing.

Each chapter explores different shades of human relationships — between friends, brothers, acquaintances, lovers, and others. They give a sense of familiarity. Is it because of the tinge of personal touch they carry or are they the results of your keen observations?

It is probably both. I began writing in my late twenties, but I realize now that I must have always been an observer, noticing little details, tics, idiosyncrasies. Now when I’m writing a story, details come back to me, yet I can't remember consciously storing them up in my memory.

How did you decide upon the title of the book?

The title came last. I thought that once I’m done writing all the stories, I’ll choose the title of the story that felt most central to the idea of the book and use it as the book title. But when the time came, none of the stories felt representative. So, as I do for my story titles, I sat back and read through the manuscript with the hope that the book title would suggest itself. I waited for a word, a phrase, a snatch of a song to lift off the pages and make itself heard or seen. When I was done reading, the title The House Next to the Factory came to me.

How would you describe the meditative process of spawning ideas and thoughts into words?

I’ll say it’s long-drawn, organic; one has to wait for things to build upon themselves. Before I start writing a story, I spend days or weeks (sometimes even months) thinking about the various characters, the scenes — often playing them out in my head as though it were a movie. Once I’m ready, I turn on my laptop and in a single sitting pour everything out, everything that I consciously or subconsciously know about the story. At this point, it doesn’t matter if the scenes don’t make sense, if the tenses are jumbled up, or the grammar, or the spellings. The aim is to get as much as possible down on paper. Over the years, I have found this regurgitative process useful in building the initial drafts.

Could you name some writers who have influenced you immensely and intensely through their works?

Premchand’s novels, particularly Godan (1936), are amongst the first books that really captivated me; R. K. Narayan’s body of work; Anita Desai’s Clear Light of Day (1980), which I return to perhaps every five years; Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay’s Pather Panchali (1929), which is again a book I find myself returning to every few years; Amit Chaudhuri’s novels, particularly A Strange and Sublime Address (1991); William Trevor’s, Raymond Carver’s and Jhumpa Lahiri’s stories.

Comments

*Comments will be moderated