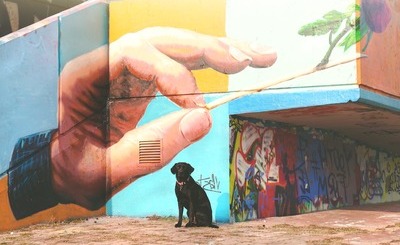

Entrepreneur and philanthropist Surina Narula at her New Delhi residence. Photos: Shireen Quadri

Surina Narula, co-founder of the DSC Prize for South Asian Literature, says the reason behind establishing the award and leaving it open is to get an understanding of the world

As an anthropologist, Surina Narula has her eyes trained on people, constantly trying to find routes to understanding worlds different from her own. As a philanthropist, she has her heart in the right place, striving to bring succor to those who need it most, from street children to scores of underprivileged women around the globe.

Married to Harpinder Singh Narula, a UK-based businessman and the chairman of the DSC Group, a construction giant, 60-year-old Surina, is a mother to three sons. An MBA and a master’s in social anthropology, she conceived the DSC Prize for South Asian Literature, along with her middle son, Manhad, in 2010. With the prize, they aimed to “celebrate the rich and varied world of literature of the South Asian region” and to bring South Asian writing to a new global audience, raising “awareness” of South Asian culture around the world.

Seven years down the line, it has been an incredibly fascinating journey for Surina and the DS Constructions. Incidentally, DSC funded the Jaipur Literature Festival (JLF) when it started in 2006. The prize, which was earlier given at the JLF, now keeps travelling to a different region every year. In 2016, Anuradha Roy won the DSC Prize for South Asian Literature for Sleeping on Jupiter (Hachette), which was given at the Fairway Galle Literary Festival in Sri Lanka. On November 18 this year, Anuk Arudpragasam was declared as the winner of the prize for his debut novel, The Story of a Brief Marriage (HarperCollins), at the Dhaka Literary Festival in Bangladesh. This year, however, the prize money, which used to be $50,000, has been slashed and is $25,000 (approximately Rs 16 lakh), still qualifying to be the richest literary award of the region.

Four other novels which were on the shortlist this year included Anjali Joseph’s The Living (Fourth Estate), Aravind Adiga’s Selection Day (Fourth Estate), Karan Mahajan’s The Association of Small Bombs (HarperCollins) and Stephen Alter’s In the Jungles of the Night (Aleph Book Company). The chairperson of the jury this year, Ritu Menon, was quoted as saying: “All five display a remarkable skill in animating current universal preoccupations in unconventional idioms, and from a distinctively South Asian perspective.”

Surina, president of the Consortium for Street Children (CSC), has previously been Co-Chair and Trustee of a network of over 65 UK-based development agencies. She is a trustee of Partnering Hope Into Action (PHIA) and the chairman of TVE South Asia. She is the founder sponsor and festival advisor for the JLF. She was on the Board of Directors for Plan International UK, and is Patron for Plan India and Honorary Patron of Plan USA and a Patron for Hope for Children, having worked in conflict zones like Sierra Leone.

“I like to observe cultural behaviours and think of ways to link them with development,” says Surina, talking about the various ways literature shapes her form perspectives on some of the issues of the region. “Reading South Asian literature helps me formulate perspectives on the developmental issues. After reading these books, when I do the development work, I understand where these people are coming from. Then, there is the scope to work differently, and work better,” says Surina, who has has received various awards for her contribution to street children charities, including the Asian of the Year Award (2005) and an MBE for charitable work in India (2008).

Excerpts from an interview:

The Punch: How has the DSC Prize for South Asian Literature, which was started in 2010, evolved over the years?

Surina Narula: Our experiences in South Asia are unique because of our culture and gender issues. It’s very different from the West. For those who are brought up in the West, it’s very difficult to understand where we are coming from. A woman in Pakistan or in Bangladesh or in Bhutan have a very similar upbringing as a woman. Though religious strife happens in the West too, what happens during that strife in South Asia is somehow unique to us. Our marriages, for instance, are different. All these aspects have been delved into the novels nominated for the DSC Prize for South Asian Literature.

For me, reading South Asian Literature has been a great eye-opener. Many people ask why I give this award. What is there in it for us? However, some good has surely come out of five years of reading South Asian Literature, even though it’s a very expensive way of reading the literature from the region, but at least I get the best.

Earlier, the Prize was given at the Jaipur Literature Festival (JLF). I used to tell them that all I wanted was the signed copies of 200 books from all the authors who come there. It was my desire to have a library. The Prize has also entailed my travels to the South Asian regions. For me, visiting these places and seeing what these people are like have been incredibly interesting. I’ve done social anthropology. As an anthropologist, I like to observe people from close quarters: What’s going on? What are they thinking? Since I work in the development sector, I like to observe cultural behaviours and think of ways to link them with development.

My passion is The Consortium for Street Children (CSC), a global network that strives to give street children a voice, promote their rights and improve their lives through advocacy, research and development. I am its founder and have seen it grow in the last 25 years. We’ve made a difference in policy. Finally, after 25 years, we have managed to get them to insert a General Comment in the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. It means that a government doesn’t have to adhere to it although they are guided towards what the UN rights of the child means. The government has to come and explain to the UN why the children in their country are dying. A General Comment means that the UN is guiding a country towards thinking of street children and their rights. For this, we had met street children from all over the world and took feedback from them. What would they like to see in the General Comment? First and foremost, they want to be recognised as human beings on the street. You can’t just look at them and say let’s remove them. You have to recognise them. They are going to be on the streets, but you have got to give them their rights over there, whatever they are. When this happened, I was in Geneva and, sitting in that room, I was thinking: It took 25 years to get one General Comment. When is it going to become the right of a street child?

Besides working for the Consortium for Street Children and Plan International, I also work for TV for environment. Reading South Asian Literature makes me work better in all these areas. We also work with children in war-torn areas. Through Plan International, I’ve gone in countries conflict zones like Sierra Leone and met children there. Reading South Asian literature helps me formulate perspectives on the developmental issues. For instance, in The Story of a Brief Marriage, Anuk Arudpragasam, the winner of this year’s prize, literally gets into the skin of his characters. He imbues the novel with micro details.

After reading these books, when I do the development work, I understand where these people are coming from. Then there is the scope to work differently, and work better. I don’t know if the award has helped or done a great deal in the world of literature, but to me personally, this entire journey of the prize has just been fantastic. It has certainly helped bring recognition to the voices who have won the award.

The Punch: You have also been actively engaged in philanthropy, with special focus on street children and women. Tell us about your other initiatives.

Surina Narula: I’m the co-founder of the Consortium for Street Children. Its idea came from the fact that there wasn’t much information available about street children all over the world. I am a graduate in Economics. When I went to London, I thought of beginning to reinvent the wheel and realised the need to learn from others. So, we formed the consortium, bringing together street children and charities. We learnt best practices from street children and that is how the consortium evolved. Being the founder, I didn’t have to be all the time worried about money for them. Even if our business went up or down, I didn’t have to worry about it because we had put in checks and balances. We had put in enough for it to grow. Since there were other trustees and other people, I could distance myself. Similarly, I started the Television For The Environment and for two-three years, I funded it and helped them set up the award.

It’s been going on for 6-7 years and now manages on its own. It is my dream that whatever we start we should not be involved with it forever because it has to function on its own; it should not stop after you die, but continues perpetually. So, my challenge is to see how the DSC Prize for South Asian Literature continues without us. The moment our businesses go down, the first things that get axed are these philanthropic ventures. When our Libya venture crashed, we had to cut down the prize money from $50,000 to $25,000. I don’t want to reach a situation where we close it. My challenge is to make it continue without me. We have to look at a way of forming a trust or whatever so that there is a method of continuing it after us because this prize is very good. There are so many prizes all around the world, but there never has been a South Asian Literature prize which recognises the people of the region. Even the Man Booker Prize was set up by a company. People ask: What is the connection between construction and literature? Why should we be giving this award? I hear it about the JLF also. What’s the connection between a construction company and JLF and why should these people be funding JLF? You have these questions because people don’t understand. They haven’t read about these prizes carefully. The Man Booker Prize came from a shopkeeper. They started it and then they got sponsors. That’s how it worked. They got a million pound funding from the sponsors and that’s how the prize continued. They have to self-sustain themselves. Even something like crowd-funding could do it. So, if enough people pitch in, the prize can carry without us.

After the JLF, I started Difficult Dialogues. My other challenge has been to figure out how to tackle policy in India. However, there was no forum to do this. I like taking such initiatives with our money. This means that we don’t just give our money away, but set up a foundation with it so that it takes care of its own and takes the work forward even after us.

There are primarily two ways of giving. First is that you simply give away your money. That is easy. The second way is that you set up a foundation and put your money in it which, in turn, gives it out. Now, I feel there is a third way of giving out your money. That way entails that you put yourself in it also. It also means that you put whatever you have learnt. Sometimes, if you have the time, you put that too. It is then that you get to do things in an intelligent manner. This way, though you give in hundreds and thousands, but you make it into a venture worth a million because you add value to it. So, I’ve been adding value to whatever I’ve been doing.

It is the same with Difficult Dialogues. I didn’t find an unbiased forum in India doing conferences to facilitate policy discussions. Policy discussions usually happen because of vested interests. Normally, you’ll find politicians discussing policies. Most of the conferences are sponsored by vested interests. So, I thought that we must have a forum where it’s possible to do unbiased discussions.

As for JLF, we told its directors (William Dalrymple and Namita Gokhale) to curate it. I was an advisor, but it is run by people who are hardcore literary. It took me a long time to tell them to add glamour to the festival. I said unless you add glamour, it’s not going to work. I do fundraising events in London and have noticed that a bit of glamour always attracts people. Earlier, at JLF, they didn’t have an actor or some other well-known person. They only used to have authors who talked to each other. It was an esoteric kind of circle. So, I sprinkled in it a dash of glamour and asked them to bring some people from the film world as I have friends there. Deepti Naval is a dear friend of mine. She has written several books. She’s also an artist. I told them to bring in people like such people, making them think differently about these people.

It’s the third year for Difficult Dialogues and I’m still trying to put it together but on the curation level, I never interfered. They always had a free hand. As a sponsor, I never throw my weight around, asking for certain things to be done or certain number of chairs to be reserved for us. So, that helped it in many ways. Similarly, I don’t get involved in curating or judging the DSC Prize for South Asian Literature because it should be a completely independent thing. That’s how it’ll be finally growing on its own and I can move away and let the baby run.

In Difficult Dialogues, I’ll be involved for five years. And then I’m hoping it’ll have its own life because it’s doing well and people are really excited about it. In Goa, the Goa University, the International Centre and the civil society are very excited about it. So, I feel they will carry on the legacy because eventually I want to retire. Next year, I want to move out of everything.

With Difficult Dialogues, my idea is to bring people from the communities’ level and from the panchayat level to figure out where, for instance, the money from Centre’s health policy go. I would organize the conference, call a woman who has had the experience of having received the money or the experience of having used or not used the money, the state-level person who is in charge for that policy, like the health secretary of that state. I would also invite some ministers who have been involved with putting the money together as well as some academics, like those associated with the University College of London (UCL) who are on think tank which forms form policies. I invite practitioners and the NGOs. At our health conference, for example, we had 20 women from Jharkhand. I went and met them there on behalf of one of my NGOs. After that visit, I learnt a lot from them. They were part of Single Women’s Association in India. Through their experience and oppression, women know much more and they can fight their battle in a better way if they are given a forum. We’ve learnt so much from these women. They have burst so many of our myths. When I took these women to Goa, they asked the health secretary the right questions. The academics from the UCL were very excited about the conference last year.

The Punch: The DSC Prize is open to writers of any ethnicity as long as they write about South Asia, which is good. Even the Man Booker Prize had to look beyond the Commonwealth and open itself to make Americans eligible. It is also significant that you include translations since there are languages other than English which are of paramount importance.

Surina Narula: The reason behind establishing this award and leaving it open is to get an understanding of the world. It had to be English literature because it’s common to all South Asian countries. It had to be open. I’ll stop giving the prize if one day a hardcore Englishman, who has lived in England and was brought up in England, taps the feelings of the eight countries, with the exact nuances, in his writing. I will then know that the world has understood us.

If any hardcore American author had written The Story of a Brief Marriage, I’d say that we’ve done it and that people have understood us. This prize has to increase the understanding of our nations among people who are working in these countries. A lot of NGOs from the US and UK come and work here and understand more about our country through South Asian literature. The panel discussion we had in London this year before the shortlist was announced was on films and South Asian Literature. Gurinder Chadha was among the panelists. Chadha was born and brought up in Southall. Her understanding of being Indian is very different from the real Indian who has been brought up in Punjab, etc. So, hers will always be the British-Indian perspective. To get to another level of understanding the culture, she will read South Asian literature. Chadha said that she felt it was very important and she wanted to buy rights of these books. Steven Bernstein, the Hollywood director, who was also there, said that South Asian literature will help us make good movies on South Asia. Since, otherwise, you have got to live in the country and breathe it to understand it. We all are different people. For the DSC Prize for South Asian Literature, the highlights are when I meet the jury members and the authors.

Today, honour killing happens in Punjab, but more in Southall. For marriages, while Indians there send their daughters to India, Pakistanis send their daughters to Pakistan. Once she gets married, they don’t want her back. They throw her passport away. That’s their way of kidnapping her and doing child marriage, which is prevalent even more in the Western countries. Even Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) happens a lot in England. It’s so shocking but now they are fighting it out. People like Yasmin Alibhai-Brown are fighting these battles. When we met, Yasmin started talking about FGM and told me many things that I didn’t know. There are many other such women who are doing similar things in their communities.

The Punch: If you could tell us about some of the issues of the region that trouble you or concern you not just as a philanthropist and an activist, but someone who’s also interested in literary traditions?

Surina Narula: Every year, when I get involved with the Prize, there is a different issue that hits me. This year, I’m working on gender. With Difficult Dialogues, in a way, I get equipped to understand how I want to help curate it. While UCL does it, I do put in some suggestions. For example, I’ve told them that this year’s theme has to be about men in a gender conference and not just women. There is a student who has done Ph.D. on men who rape women in India. She took interviews of hundreds of people in prison who have raped. They all said that they didn’t rape. The understanding of these men is that this is normal. Getting physical with a girl who is not consenting is a norm in India. In England, a senior filmmaker said to me: ‘Between you and me, Surina, in India, you can’t have sex if you wait for the consent of a girl.’ (India mein toh aadhi ladkiyon ke saath sex hi nahi hoga agar unki haan ki wait karte rahoge toh). Can you imagine? This is the thinking! The filmmaker hinted that in their times, girls never used to say yes. But they would still have sex with them because a girl who says yes is promiscuous. How can she want sex? A girl can’t want sex in India because it’s wrong.

The man thinks that it’s a norm to get physical with a woman. If men think this is right then, according to them, they are innocent. Men are also in the man-box and they are trapped too. In India, when I asked some universities to work on the gender issue, they just had women. I insisted on asking men’s perspective on gender equality. I want to know what men are thinking, if they are thinking about gender equality. Even women say that the man allowed me to do this or that. Why do men have to allow women to do this or that? That’s what this conference deliberates. How did I think about including men in this dialogue? Through literature and meeting different kinds of people. For me, the prize opens up so much. And, hopefully, it does for other people as well.

The Punch: What do we must do to make this world a better place to live in?

Surina Narula: Sri Aurobindo said some very great things. He talked about self-governance a lot, which is an amazing concept. Whatever the state we are in, unless all of us have self- governance, the world will not be right. How can we self-govern? Today, there is enough information and things have been revolutionized with information technology being available to anybody. We are living in a world where we can access a lot of information and with all that information if we start self-governing ourselves, I think that’ll lead to a better world. That is the only way forward.

For me, environment is going to determine the boundaries of this earth eventually. People who live in a particular region are going to identify with each other more than people with religion or political concerns. My father always said, ‘Don’t talk big. Just do your bit and share with people.’ Though I don’t believe in religion, I admire the three tenets of Sikhism: Think of God, earn your goodness, share everything.

The Punch: When you look at the world around you, what are some of the things that lift you after you see your interventions fructifying, bearing fruits somewhere?

Surina Narula: If the DSC Prize for South Asian Literature is empowering someone to do better work, getting them to write a better book or giving them enough time to do it, if writers don’t have to look for money at least for the next 3-4 months but just work on another book, I think that is very exciting in itself. Otherwise, there is so much to do in this world. One is never satisfied with the work. One lifetime is not enough. With Difficult Dialogues, it’s just coming to a point where I can speak to academics, sit next to them and say listen to my point of view too. Initially, when I started all this work 25 years ago, I was very shy and in awe of people who had written books. Gradually, over the years, I’m getting more confident. I now feel that I also have a point of view and I can speak.

Soon, I’m going to meet one of the top feminists of this country. The last time I sat with a feminist (Gloria Steinem) at a panel at JLF, I learnt a big lesson. I shared with her that I had been studying a lot about prostitution all over the world and wondered why we couldn’t legalise it. After all, it’s been going on forever. So, it should be legalised now so that women have more rights. She told me that ‘decriminalising’ was the right word, which means that prostitutes should not be hauled up and taken into custody. It should be the people who are using them. Prostitutes should get their rights as women. But the moment you say legalize prostitution, you are giving women another job and making them more vulnerable. In countries where it’s legal, if one goes for a job interview, they offer them the job of a prostitute. After Gloria explained all this, I understood it completely. My thinking process was wrong. Decriminalisation is what is needed, not legalising it.

The Punch: As someone who shuttles between cultures and continents, how do you look at the ideas of belonging and home?

Surina Narula: I don’t think that home is a place. I think home is where your children and family are at the moment in time. So, if my family is gathered in Maldives in a hotel, that’s my home in that moment. That’s how I look at life now as those moments are so rare. I’m travelling constantly and am always on the move. I feel I’m the citizen of the world. Sometimes, I wonder what I will do if there is a war. I’m also an American and a British, apart from being an Indian. However, my heart is in India. I belong here.

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated