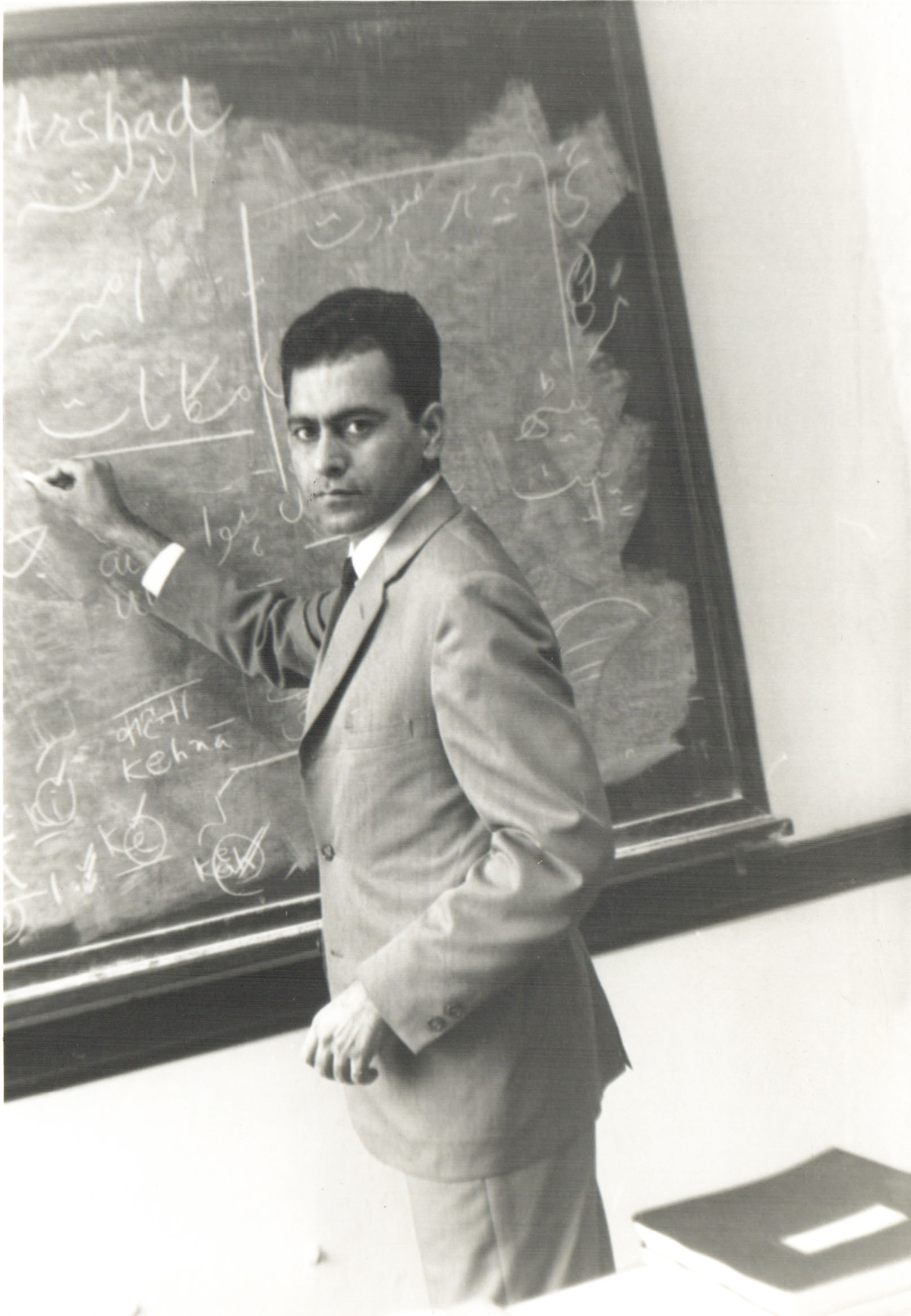

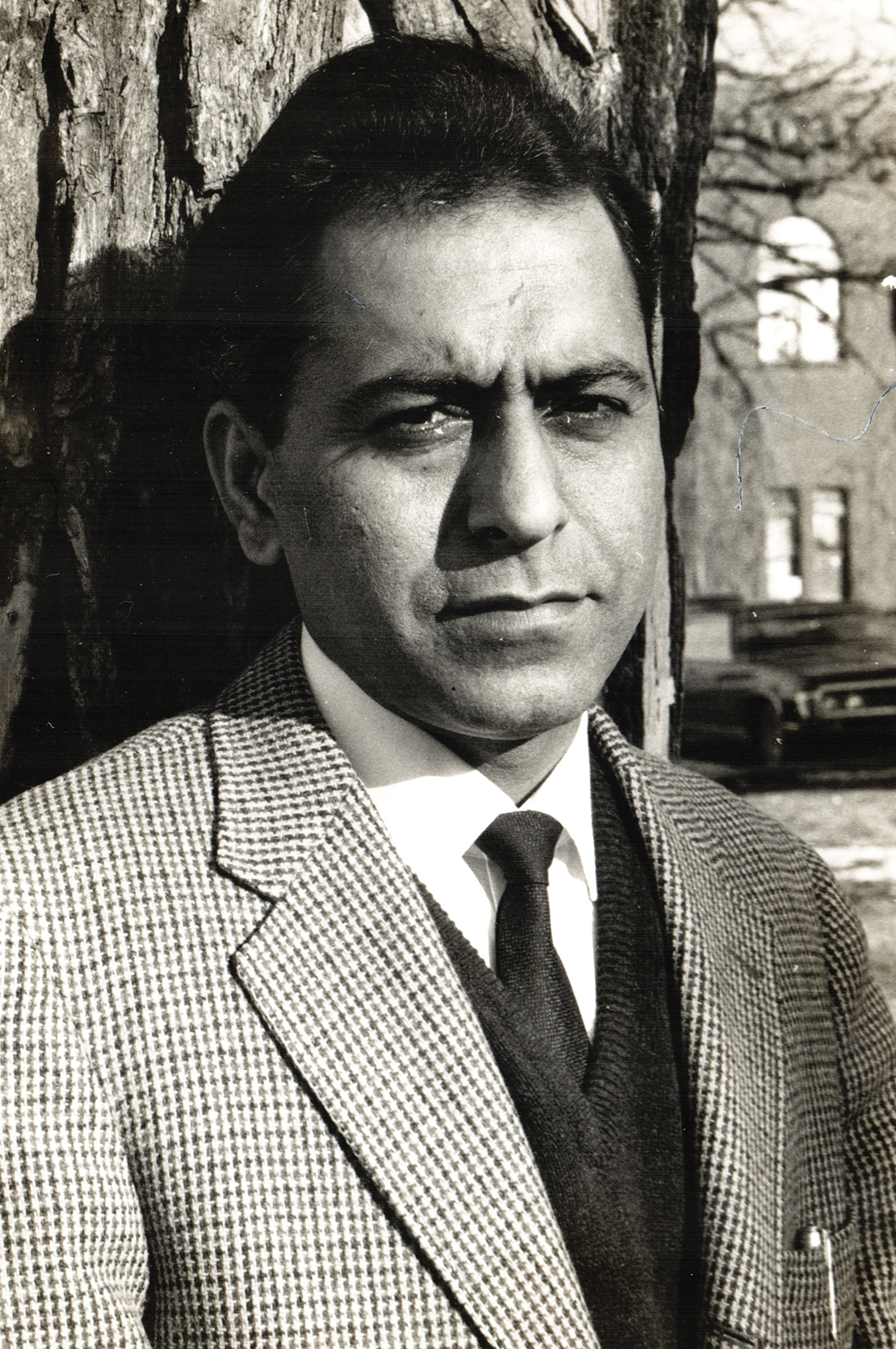

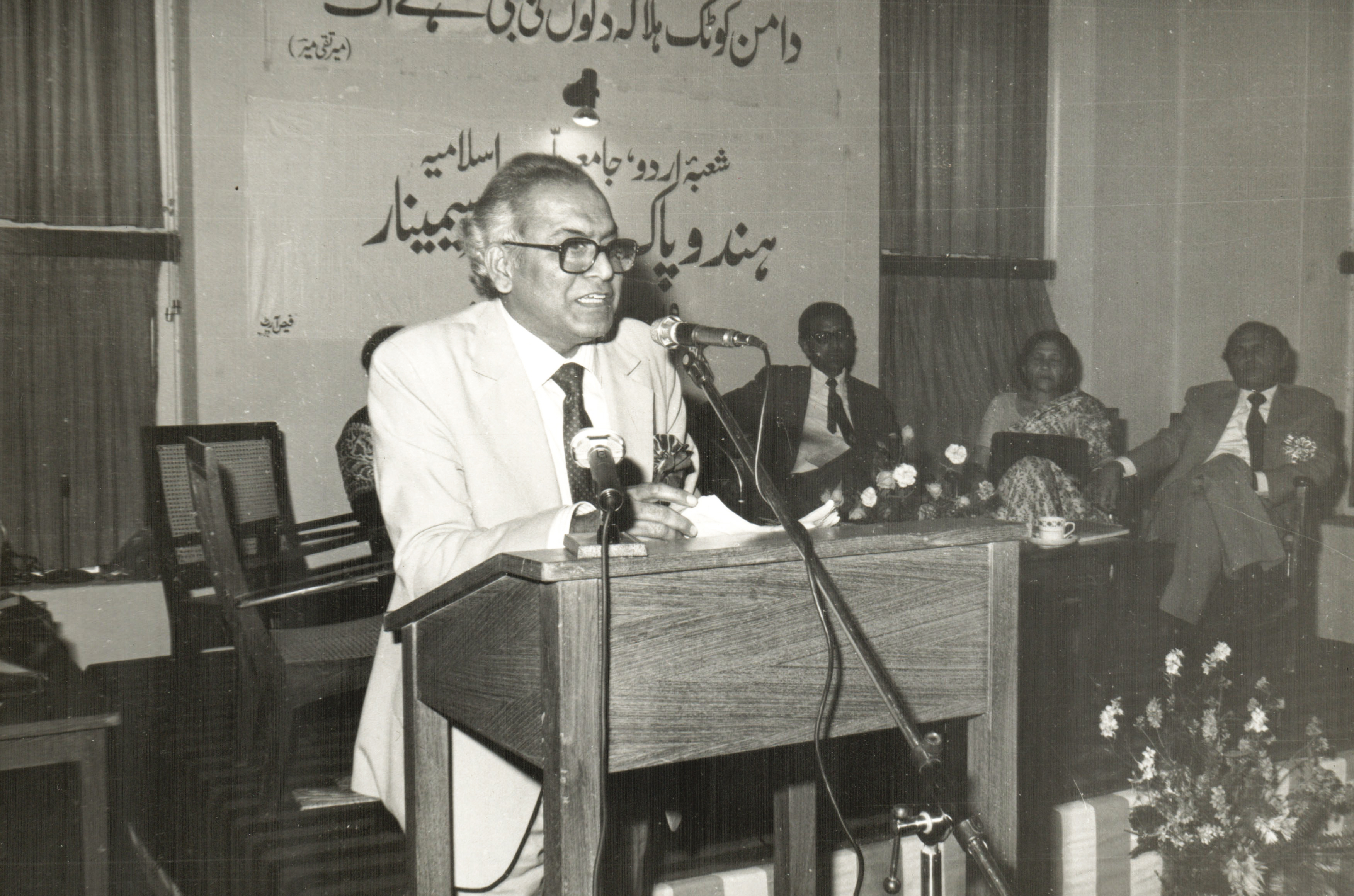

Professor Gopi Chand Narang. All photos courtesy of Gopi Chand Narang.

Professor Gopi Chang Narang, 91, is an institution unto himself. A formidable literary theorist, critic and scholar, he has published more than 65 scholarly and critical books on language, literature, poetics and cultural studies: twelve in English, eight in Hindi and more than 40 in Urdu. In his works spanning decades, the Professor Emeritus at University of Delhi and Jamia Millia Islamia has incorporated a range of modern theoretical frameworks, including stylistics, structuralism, post-structuralism and Eastern poetics.

Born in Dukki, a small town in Balochistan, in the British India (now in Pakistan), to a Saraiki family — his father, Dharam Chand Narang, was a litterateur himself, and a scholar of Persian and Sanskrit, who inspired in his son an abiding interest in literature — Professor Narang received a Master’s degree in Urdu from the University of Delhi, and a research fellowship from the Ministry of Education to complete his PhD in 1958. He taught Urdu literature at St. Stephen’s College (1957-58) before joining Delhi University, where he became a reader in 1961. In 1963 and 1968, he was a visiting professor at the University of Wisconsin, also teaching at the University of Minnesota and the University of Oslo. He joined Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi, as a professor in 1974, and rejoined the University of Delhi from 1986 to 1995. In 2005, the university named him a professor emeritus.

Professor Narang’s first book (Karkhandari Dialect of Delhi Urdu) was published in 1961, a socio-linguistic analysis of a neglected dialect spoken by indigenous workers and artisans Delhi. Professor Narang has produced three studies: Hindustani Qisson se Makhooz Urdu Masnaviyan (1961), Urdu Ghazal aur Hindustani Zehn-o-Tehzeeb (2002) and Hindustan ki Tehreek-e-Azadi aur Urdu Shairi (2003). Amir Khusrow ka Hindavi Kalaam (1987), Saniha-e-Karbala bataur Sheri Isti’ara (1986) and Urdu Zabaan aur Lisaniyaat (2006) are some of his socio-cultural and historical studies.

In addition to teaching, Professor Narang was the vice-chairman of the Delhi Urdu Academy (1996-1999) and the National Council for Promotion of Urdu Language (1998-2004) as well as vice-president (1998-2002) and president (2003-2007) of the Sahitya Akademi. He was Indira Gandhi Memorial Fellow of the IGNCA (2002-2004), and Rockefeller Foundation Fellow for Residency at Bellagio Study Centre, Italy (1997). He received Mazzini Gold Medal (Italy, 2005). He was a fellow of the Royal Asiatic Society, London, UK and his invaluable contribution to literature is acknowledged in the Dictionary of International Biography, Cambridge, UK. He is the only Urdu writer honoured by the Presidents of both India and Pakistan. In 1971, he got the President’s National Gold Medal from Pakistan for his illuminating work on Allama Iqbal. He was awarded Padma Bhushan in 2004 and Padma Shri in 1990.

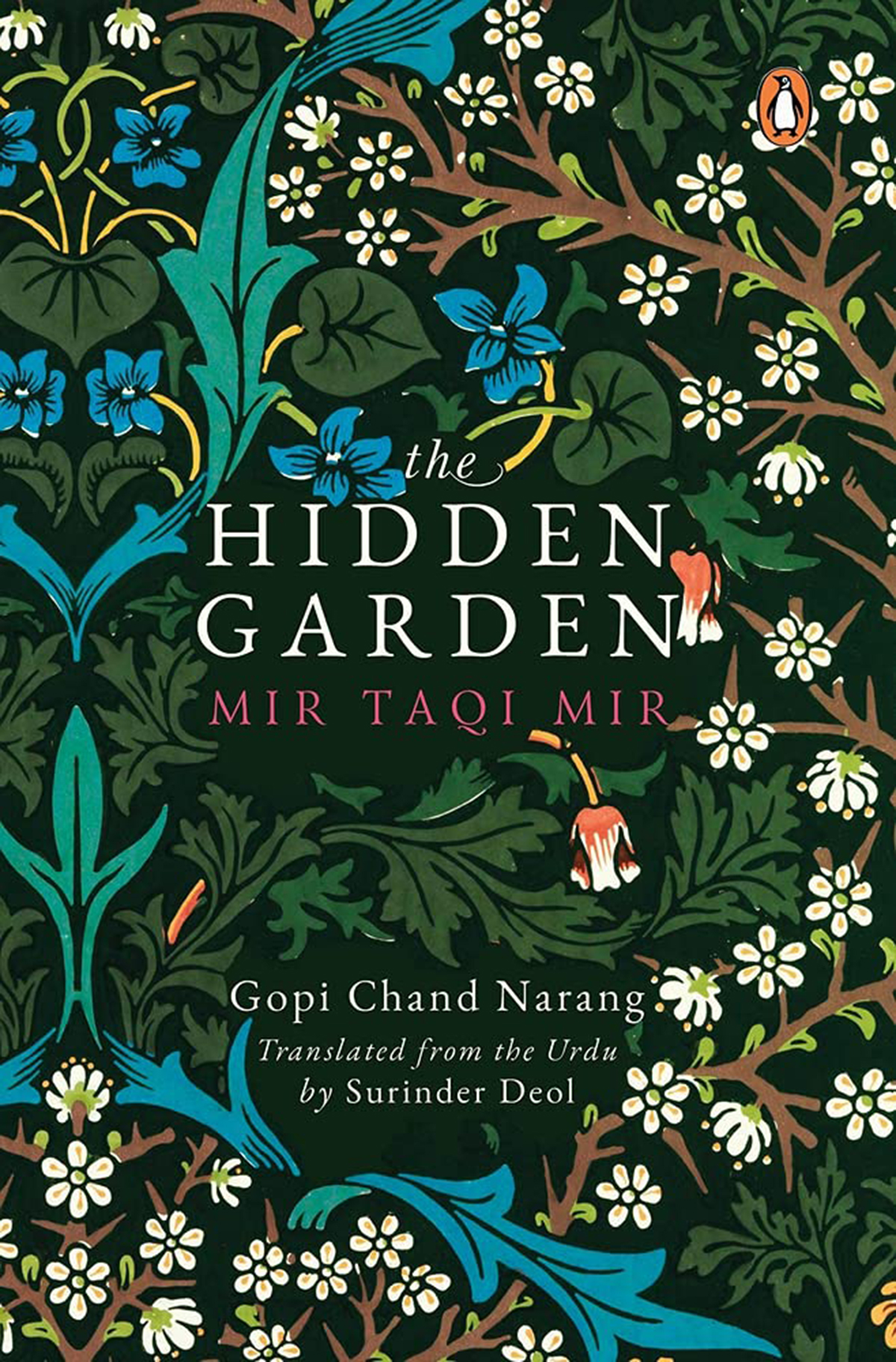

In 2017, Oxford University Press published Ghalib: Innovative Meanings and the Ingenious Mind, the translation of Professor Narang’s seminal book on Ghalib by Maryland-based author and poet Surinder Deol, who served as a program manager and a senior specialist at the World Bank in Washington, DC. In 2020, Deol translated another of Professor Narang’s landmark book, The Urdu Ghazal: A Gift of India's Composite Culture, published by Oxford University Press. His recent release, The Hidden Garden: Mir Taqi Mir (Penguin Random House), translated from Urdu by Deol, introduces readers to the life and poetry of the grossly misunderstood poet, Mir Taqi Mir (1723-1810), who is widely admired for his poetic genius. “My work on Mir, which started in the early 1980s, is one continuous search for the essence or the core of his distinctive poetry for which he is called khuda-e sukhan (god of Urdu poesy),” says Professor Narang.

(Note: This biographical sketch has been compiled with inputs from the author bio provided by Professor Narang’s publishers as well as Wikipedia entries)

Excerpts from an interview:

Nawaid Anjum: Your new book, The Hidden Garden: Mir Taqi Mir, gives us a glimpse into the life and times, and the poetry of Mir (1723-1810), the first poet to lay bare the hidden beauty and genius of the Urdu language. What are the distinctive attributes of Mir’s poetry that mark his reputation as a pathfinder, as a master poet who held a sway over the imagination of several poets to come, including Ghalib?

Gopi Chand Narang: Mir lived during extraordinary times. The Mughal rule that had provided political stability for a long period of time was teetering between tragedy and farce. The final nail in the coffin came in the form of massive foreign invasions, massacre and plunder of Nadir Shah and Ahmad Shah Abdali. Persian language that had a great hold on the local poets’ imagination started to lose its appeal as Rekhta, a pluralistic language and a by-product of the composite culture of India became a viable option. A major voice in this transition was that of Mir Taqi Mir who made very effective use of the new evolving medium reflecting voices of the people heard in the streets of Agra and Delhi. Mir wanted to reach out to people and the vehicle for that was not the Persian style that was understood and appreciated only by the literati, not the common folks. Listen to his words:

she’r mere hain sab khwaas pasand

par mujhe guftagu awaam se hai

My poetry is appreciated

by the sophisticated

But I address

the common people.

Parhte phareinge galiyon mein in rakhton ko log

Muddat raheingi yaad ye baatein hamaariyaan

People will keep reciting my rekhta ghazals in towns and alleys

They will keep echoing them through the centuries.

He wrote simple words, enriched by innovative metaphors and similes. His simplicity had deep structure and dense meaning. At the end, he could legitimately claim:

rekhta rutbe ko pahunchaaya hua us ka hai

mo’taqid kaun nahien Mir ki ustaadi ka

If Rekhta reached the pinnacle of its greatness,

this was the work that he accomplished.

Is there anyone who does not accept

Mir’s master mysterious touch?

Nawaid Anjum: You argue that a serious critical look at Mir’s multi-dimensional work must go beyond traditional theses that hail his poetry for its “simplicity and flow” and also for combining the rawness of Agra’s Braj with the sophistication of Delhi’s Persian and mellowness of Lucknow’s Awadhi in his diction. Why do you think the simplicity of his poetry is deceptive?

Gopi Chand Narang: Mir’s greatness as a poet does not depend on one or two factors. A serious critical look into Mir’s work must go beyond traditional theses of simplicity and flow and a synthesis of Persian segments with Prakritik Rekhta. There is much more to Mir’s simplicity. A quick assessment does not complete the picture. Mir was the first great Indian poet who used multiple lenses in his work. His deceptive simplicity was in fact his “multiplicity.” There is an impression that simplicity of the syntactic structure equals simplicity of poetic meaning which is not correct. This book establishes for the first time through textual analyses that Mir speaks in a dialogic language that apparently looks like conversational, but his simplicity is deceptive. It is an established fact that conversational language is not poetry’s language. The poetic language infused with creative devices when removed from the language of daily discourse becomes more meaningful and durable. Look at the following couplet:

kaha main ne kitna hai gul ka sabaat

kali ne ye sun kar tabassum kiya

I asked the rose bud,

“How long is the life of a flower?”

The bud listened and smiled.

Nawaid Anjum: What are the hidden aspects of Mir’s vast oeuvre — six divans — that you have been trying to unravel, an exercise that resulted into your landmark book, Usloobiyaat-e-Mir (1984)? From that book to this, you have opened a new vista on the study around Mir. What did you set out to achieve in both?

Gopi Chand Narang: My work on Mir, which started in the early 1980s, is one continuous search for the essence or the core of his distinctive poetry for which he is called khudaa-e Sukhan, God of Urdu Poesy. There were so many misconceptions about him that I had to raise my voice to correct those fallacies. Mir was a multidimensional poet (“a poet of countless delights”). Critics tried to put him in a box. That was unfair and wrong. The label of simplicity was framed in a way that it degraded Mir’s work. This had to be corrected. Mir had a good mastery of Persian, but he was right in his assessment that a time had come to create a synthesis of Persian and Rekhta. I end my book by calling Mir a “complete poet.” He had the mastery of style and lyricism and he could create magic using his words. In fact, he was the first “ustaad poet” of Urdu, as he claimed in one of his couplets. Furthermore, he is not only a love poet as other love poets are, he is a metaphysical poet par excellence reflecting rainbow like synthesis of the Bhakti and Islamic Sufi thought.

rekhta rutbe ko pahunchaaya hua us ka hai

mo’taqid kaun nahien Mir ki ustaadi ka

If Rekhta reached the pinnacle of its greatness,

this was the work that he accomplished.

Is there anyone who does not accept

Mir’s master mysterious touch?

Jalwa hai mujhi se lab-e daryaa-e sukhan par

Sad rang meri mauj hai main tab’e-e rawaan huun

Around the banks of the river of poetry mine is the true spectacle

In my tumultuous waves there are hundreds of colours, I am the gushing river!

Gopi Chand Narang was born in the small town of Dukki in Balochistan, which is on the border between Pakistan and Afghanistan. His father, Dharam Chand Narang, was a scholar of Sanskrit and Persian.

Gopi Chand Narang was born in the small town of Dukki in Balochistan, which is on the border between Pakistan and Afghanistan. His father, Dharam Chand Narang, was a scholar of Sanskrit and Persian.

Nawaid Anjum: In your preface, you write how you encountered Mir for the first time in your early twenties when you were studying in Delhi University. Tell us more about this early encounter with the first Urdu poet whose works enthralled you. What struck you the most about his poetry? How did your appreciation for Mir’s lyrical and romantic poetry get deepened when you read his autobiography, Zikr-e-Mir, and Mohammad Husain Azad’s Aab-e-Hayaat? Though literary criticism was non-existent at that time, what role do you think the scholars at that time, like Maulvi Abdul Haq, Nawab Jafar Ali Khan, Waheeduddin Saleem and Dr Syed Abdullah play in the critical evaluation of Mir’s work?

Gopi Chand Narang: There is a difference between what one hears and what one experiences. As a student of Urdu, I had read Mir’s poetry, just as I had read other poets. But when Khwaja Ahmed Faruqi asked me to look at the proofs of his book, I had to do that job at a slow pace, carefully looking at each word. This was an enlightening experience for me. I went deep into Mir’s syntactic structure, his use of metaphors and similes, the mellow and sometimes roaring sounds of the music of his phonics and his mixing of different styles of writing poetry. It didn’t take me long to realise that what experts had written about Mir was half-baked and basically subjective and unjustified. This whole talk of 72 nishtars and Mir being a simple poet of only 72 shers was a crisp quip but was a bogus critique, which in fact denigrated Mir. Such remarks need to be challenged and had to be exposed by tools of scientific criticism based on textual analysis and exposition of the inner creativity and aesthetics of the deep structure of Mir’s poetry.

Nawaid Anjum: What is the contribution of Firaq Gorakhpuri and Nasir Kazmi in the revival of Mir’s work? Do you see these two poets’ own sensibilities as having been moulded by Mir’s ingenuity and the thematic concerns of his poetry?

Gopi Chand Narang: It is a great challenge to carry on the tradition of a great poet like Mir. The task was even more difficult because 19th century Urdu poets were so much influenced by the Persian style that they never paid much attention to Urdu “of the street” that was evolving into a beautiful language thanks to Rekhta and Khari Boli. Firaq, because of his deep understanding of languages such as Hindi, Sanskrit, Khari Boli, Urdu, and Persian, understood the essence and anguish of Mir’s voice. Firaq’s creativity was deeply inspired by Mir. Nasir Kazmi’s forlorn and despondent indigenous voice was influenced both by Mir and Firaq. The revival of Mir in present times is the legacy of both of these poets.

Page

Donate Now

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated