Poet, lyricist and filmmaker Gulzar. Photo: Vivek Ranade

Rooh dekhi hai kabhi?

Rooh dekhi hai, kabhi rooh ko mahsoos kiya hai?

Jagte jeete hue doodhiya kohre se lipatkar

Saans lete hue is kohre ko mahsoos kiya hai?

Ya shikare mein kisi jheel pe jab raat basar ho

Aur paani ke chapakon mein baja karti hon taaliyan

Subkiyan letee hawon ko kabhi bain sune hain?

Chaudhwin raat ke bfarb se ek chaand ko jab

Dher se sayee pakadne ke liye bhagtein hain

Tumne sahil pe khade girje ki deewar se lag kar

Apne gahnaate hue kokh ko mahsoos kiya hai?

Jism sau baar jale tab bhi wahi mitti ka dhela

Rooh ek baar jalegi to woh kundan hogee

Rooh dekhi hai, kabhi rooh ko mahsoos kiya hai?

(Have you ever seen the soul?

Have you seen the soul, ever felt it?

Embracing the alive milky mist

Breathing, have you ever felt the mist?

Have you seen the soul, ever felt it?

The fog, fully alive and breathing

Being embraced by the milky mist?

Have you ever experienced it?

Or, having spent the night in the shikara on a lake

The sound of the oars clapping the water

And sobbing of the winds

Have you ever heard it?

When many shadows run to catch the full moon

Standing against the wall of the church on the shore

Have you felt you womb….?

Full moon…chased by many shadows

You on the sea shore close to the church wall

And the song of your womb humming

Have you ever felt it?

Body, burnt a hundred times, changes to a mere clod of earth

Soul, burnt once turns into gold

Have you seen the soul, ever felt it? )*

* Translated by Saba Mahmood Bashir

Gulzar, the wordsmith, may have donned many hats in his career of over six decades, but first and foremost, he remains a poet and it is sheer poetry that permeates whatever medium he chooses to showcase his creativity in. He has directed 17 films and all of them have poetry in each and every frame. It will not be wrong to say that his films are poems on celluloid, poetry being the backbone of his visual medium. What is not well-known is that Gulzar has been writing film as well as non-film poetry side by side — all this while. If he wrote a song each for both Kabuliwala (1961) and Bandini (1963), he also brought out Ek Boond Chaand (1962)and Jaanam (1963). Although, the script was Devanagari for both these anthologies, Gulzar says the language was Hindustani.

In an earlier interaction with this interviewer for her doctoral thesis, Gulzar defined poetry as “binding words together in rhythm”. Poetry, to him, starts where music ends. He said that while metre has been in vogue since the times of Vedas and Purana, poetry has turned more and more individualistic in nature in recent times. “Every poet tried to speak in his own style, in which the rhythm remained but the metre and rhyme started disappearing. In this effort to maintain form, a lot of words were used with little meaning. Many a times, to maintain the midline rhyme, the poet had to negotiate through different paths so that it could exist. Gradually, what emerged was blank verse where there is rhythm and metre, but the requirement of the rhyme had to be abandoned. The thought was communicated as briefly and tightly as possible and they called it free verse. This is how I look at poetry,”he had said.

The poet, lyricist and filmmakers underlines that people have prejudices and divide languages. In fact, in a triveni, a three-line form of poem, where like the mythological and hidden Saraswati river, there is a hidden meaning after the first two line, Gulzar has spelt this out rather clearly:

‘Aao ab zabaanein baant le apni apni hum

Na tum sunogee baat na humko samajhna hai

Do anpadhon ko kitni mohabbat hai adab se ’

(Come, let us divide our languages

Neither will you listen, nor do I have to understand

How much love for literature amongst two illiterates)**

** Gulzar, Triveni, p 61

Gulzar has an interesting connect with languages and he uses it in the most distinct manner in his poetry. One finds him blending different languages in the same poem and he explains this by claiming all languages as his very own. His criterion to use words has been not only the meaning but also on the sound and its connection with the readers.

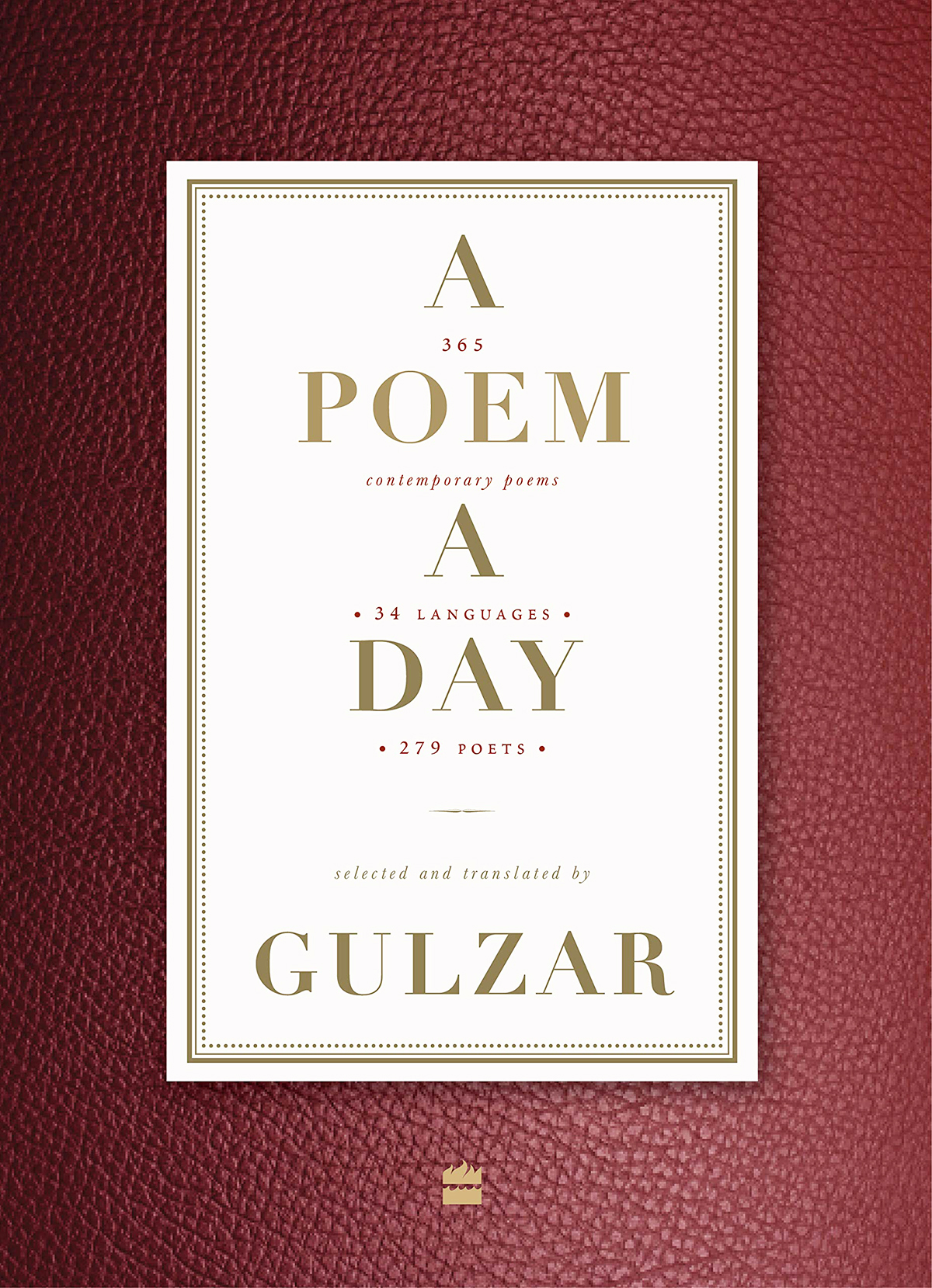

It is this flair for the different languages that he knows led him to the path of translation, too. Earlier, he has translated the Marathi poet, Kusumagraj and the Bengali poet, Tagore, and now the much-awaited anthology, A Poem A Day (HarperCollins India), where he has collated and translated 365 poems.

A Poem a Day: 365 Contemporary Poems, 34 Languages, 279 Poets

Selected and Translated by Gulzar

HarperCollins India

pp. 968, Rs 3,999

“School mein the to shayari padte bada maza aata tha. Ustaad bhi bade maze le kar sunate the aur samjhate thhe. Shayar bahut badi shakhsiyat lagte thhe. Shayad tabhi shayar hone ka jazba paida hua ho. Aazadi ke pehle ke din thhe woh. Shayar aazaadi ke aandolan ki baat karte thhe. Shayari mien utsaah tha. Ek inspiration thi.”

(We used to thoroughly enjoy reading poetry when we were in school. The teachers would enjoy reading poetry to us, explaining to us. Poets seemed to have a persona. Maybe, it was then, that I started nurturing the desire to become a poet. These were the days before independence. The poets were talking of revolution, of independence. There was fervour in poetry. There was an inspiration.)

These are the powerful words from the opening of the book, A Poem A Day, setting the book in perspective. The book is spectacular — not only as the first impression that it gives but also as one sinks into it. Although the title does give away the fact that there are 365 poems in this book, one for each day, what it doesn’t mention is that these are poems from 34 Indian languages, written by 279 poets, handpicked by Gulzar. And, as one goes further into the realms of this magnificent book, one realizes that it is the history of the nation, of the last eight decades, through poetry.

Excerpts from an interview:

Saba Bashir: To begin with the beginning, Gulzar saab, the very first question that comes to mind is about the coming together of this book. Would like to know, how did you conceptualise this book?

Gulzar: There are a couple of things which I would like to set out in the beginning.

I had been noticing a certain attitude towards poetry, generally in schools and colleges, that the same poets, and many a times, the same poems have been taught over the years. The curriculum doesn’t go beyond Shakespeare, Wordsworth, Coleridge and Ghalib! This, in a way, has resulted in a disinterest among the students because they are unable connect to it. The poetry that they read doesn’t seem relevant to them. It doesn’t touch their lives in a manner it should. I mean, we had read Julius Caesar when we were in school, and this generation is still reading it. I was questioning the relevance of the literature, of the poetry we were reading.

Generations have changed since we have gained Independence. One can relate to Faiz’s yeh daagh daagh ujala, yeh shab ghazeeda seher, woh intezaar tha jiska, yeh woh seher to nahin or to Amrita Pritam’s ‘Aaj Aamkha Waris Shah Noo’. These were the poets I was listening to. Found them relevant. One can actually appreciate poetry when one connects to it, finds it relevant. And, maybe, I was so enamoured by these poets that I too became a poet.

Now, coming to this book, I have started it from the poetry of 1947— from Independence and the Partition! But as I started thinking of the poetry from around the period, I realized that I was only looking at the literature from the north! What was happening in the South? In the East? What was being written in the west? I wanted to find out about the poetry that was being written in the different parts of the nation. And if one wanted to know what was happening in the entire country, one couldn’t look at one language! One can only touch the eye or the nose in one language! Or maybe just the moustache or the beard (he laughs). To touch the entire face, one needs to touch the different languages.

I personally know 6-7 languages and I started reading the poetry from these languages. Wanted to know all what was being written in it —reread the writings of many, like Kusumagraj in Marathi and Sunil Gangopadhyay in Bengali. Then I went beyond these languages. I delved into the poetry of K Satchidanandan and many more. It was then the churning began.

In fact, I had a conversation with Karthika, the then chief editor at HarperCollins. She wanted me to do a book of poems on Indian poets. Thinking of a book of poems from different Indian languages, the first image that comes to mind is that of a forest. A very dense forest. But as I started travelling inside this jungle, I released that though it seemed so dense from the outside, once inside, I could pave way for myself. Before others, it became a journey for myself!

No author writes in a vacuum. This was even more apparent as I read different poets — their writings reflected the issues that they were struggling with, what was impacting them — the language agitation, the Naxalite movement, the feminist movement, and so on! Ultimately, this book brings together a full landscape of the nation. It is the vista of what I saw. By the time, I crossed a hundred poems, I had found my way. It became an important book for myself, for sketching the poetry of the nation through its history.

And, that is how A Poem A Day was conceptualised.

Saba Bashir: Looking at the sheer volume of the book, one can imagine the kind of effort that must have gone into collating and then translating it. What kind of pattern did you follow in choosing these poems? How did you make this selection?

Gulzar: Indian languages go beyond its borders. We share art, literature and poetry with our neighbours. Pakistan has Urdu, Sindhi and Punjabi poetry. Sri Lanka has Tamil poetry. Bangladesh, of course, has Bengali. There is Nepali and Tibetan. Many followers came with Dalai Lama. Generations have passed since then and people who haven’t seen Tibet are writing about it, longing for their country.

The languages came connecting on their own. It has been an extremely interesting experience to unravel the versatility, the beauty in language, music, art — the cosmopolitan and secular.

Saba Bashir: Yes, I did notice the poems from the sub-continent and now it is clear why you included them here. Another interesting feature of the book is the inclusion of such powerful poetry from the Northeast India. You went beyond the scheduled languages in the Constitution. There are poems from 34 languages in this book, and a few languages which many people haven’t even heard of, for example, Korborok and Kunkana (and not, Konkoni, that one may assume).Could you please tell us about these languages?

Gulzar: Kunkuna is a tribal language on the Gujarat border whereas Konkani, from the coastal Karnataka and Goa, which is written in two scripts, is full of Tamil and Marathi words.

Korborok is from Tripura. Tribals have dialects also. I wanted to go beyond the set languages from the Constitution and choose poems that were powerful and representative of the times. There is always a talk about script, too. Like, Punjabi is written in Gurmukhi and Shahmukhi also, which has come from the Urdu script. There is always an overlap, a blending. That is the beauty.

And it is not that I chose these 365 poems. I had more than 400 poems and then sifted through them. It took me nine years to bring this book together.

Saba Bashir: That is fascinating. How did you choose the poets? Is there any poet that you wanted to include but you had to exclude for some reason?

Gulzar: It was a, more or less, a period-wise selection. For example, I translated 8-10 poems of Sunil Gangopadhyay but then chose only three. I did not pick up more than three poems of any poet. I chose these three because all of them had a different attitude, something different to say. Arun Kolatkar writes so beautifully and again I chose three of his poems.

I included the powerful poem of Jayant Mahapatra titled“Progress,” which was based on the tragic incident of 1999 when an Australian missionary and his two young sons were burnt alive. I could not skip that. But that poem did not represent Mahapatra as a poet so I included two more. I think, he is one of the greatest contemporary poets.

In Punjabi, it was Amrita Pritam who represented an era. Harivansh Rai Bachchan’s “Madhushala” was too iconic a poem to be missed. Same was the case with Sahir’s “Taj Mahal”. How can you miss Faiz!

There were a number of reasons of including a poet, or for not including. For example, there was a poet who wrote well but didn’t write later on. (The criterion was that) a poet should have had at least two collections and must have continued to write.

I did not divide the women and men poets. For example, Kamala Das was a poet who could not be ignored. Same was the case with Parvin Shakir and Zehra Nigah.

Then, ghazals have been written in many languages… Marathi, Tamil, Hindi…it was important that a ghazal by Dushyant Kumar be included. So, I asked Harish Trivedi to translate, ho gayi hai peed parvat si pighalni chahiye.

Saba Bashir: I noticed that you have included some film poets too, like Jaan Nisar Aktar, Sahir Ludhianvi, Javed Akhtar and Prasoon Joshi. Apart from these, you have also included two poets, which people generally know as actors — Meena Kumari and Deepti Naval. Would you like to say something about these poets?

Gulzar: These were poets from my field. They were writing both film and non-film poetry. But many do not know of the poet who used to go to mushairas with the takhallus, “Naaz”. Yes. That was Meena Kumari. I thought it was worth reminding that there was more to her. Deepti Naval also has published work.

Saba Bashir: The book claims that there are 365 poems, but I discovered a hidden gem —an extra poem, the 366th one for the leap year and as it turned out, it is yours — the very lovely poem from the film, Ijaazat, mera kuchh samaan. How did you choose this one?

Gulzar: That was Udayan Mitra’s contribution to the book! Here, I would like to add that Udayan Mitra and Ananth Padmanabhan of HarperCollins helped a lot. Both of them were extremely supportive and I give them full marks to help me with this project. And, yes, Farhana, too… she kept records, files, keeping a track of the sources. She, too, did a big job!

Coming back to the last poem of the book, Udayan argued that it has all the elements of a poem and cannot be missed out. So, it was taken as the 366th poem, one for the leap year.

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated