Tea Nursery and garden in Dooars. Photo Sathya Saran

Day three on of our whistle-stop tour of gardens, where we are treated like royalty by each of the senior managers who play host, sees us rattling along barely there roads seeking elephants. A 300-strong herd has been reported at Lakhipara. It is not a sight we want to miss; we can quite imagine the impact a photograph will have, if we manage to get one, for the book.

Elephants have a way of being invisible, silent. Often people who encounter them talk about how they find one standing close enough to touch, having approached soundlessly. In the greenest of surroundings their dark mass can seem to disappear unless you are extremely sharp-sighted.

Our drive is a dramatic one. Navneet Krishan, our host at Lakhipara, shows us a series of houses along the road which the elephants have destroyed. A roof has been peeled off, and an entire wall is missing. Luckily, it was not living quarters, but an Integrated Child Development Services (ICODS) structure, where children were fed khichadi. Yet, we see lines of cottages along the road, and can only hope no elephants decide to visit them. ‘Some solar lights have been put up to help spot herd movement,’ he said, ‘after an elephant crushed a sleeping man’s head.’

The Lakhipara gardens are in two parts with a highway dividing it. Characteristic of this garden are the endless, neat rows of silver oak trees that line the roads, standing like graceful maidens to welcome visitors. Soothing to the eye and a pretty break from the endless rows of low green land formed by tea plants, it makes the garden picturesque indeed.

It lies bang in the midst of the elephant district. The pachyderms come in from further north, from as far as the Manas wildlife sanctuary in Assam, sometimes give birth here and go back. At times, great damage is caused by a young male who stays back and goes into musth. Small families of elephants often hangs around in the jungles in and around the gardens and so it is inadvisable to take evening walks, says Krishan; one may walk straight into a beast as it ambles along on its evening constitutional. Damage, he says, happens when man encounters beast and reacts in fear. So the garden has men who track spoor and warn the labour to keep away from areas where the elephants could be moving in.

Margaret’s Hope Tea Estate. Photo: Sathya Saran

Of course, all this talk raises our expectations. So we drive along, eyes peeled. But it is all to no avail. Krishan has posted men along the known routes that elephants prefer and he often stops to check. Finally, after we have crisscrossed the gardens in vain, one of the scouts informs us that there is a group of animals, about six, but they are hidden deep in the forest inside the garden.

Much as we would love to see them and take photographs, the danger is obvious. We drive cautiously around, but the pachyderms elephants do not show themselves; they seem to have simply vanished.

There is a good chance they may wander back at night, causing red alerts all across the garden, so we are advised not to stay overnight at Lakhipara. Which is a pity because we have discovered common ground with Sangeeta Krishan and would have loved to compare notes with her. She currently works as a student counsellor for schools and her daughter works with Vogue. Before evening falls, we drive back to spend a second night at Meenglas, another of the company’s gardens in the Dooars, the only place where we spend two nights in a row. And quite gladly as the Bajars, our wonderful hosts in their magnificent bungalow, are excellent company and wonderful hosts.

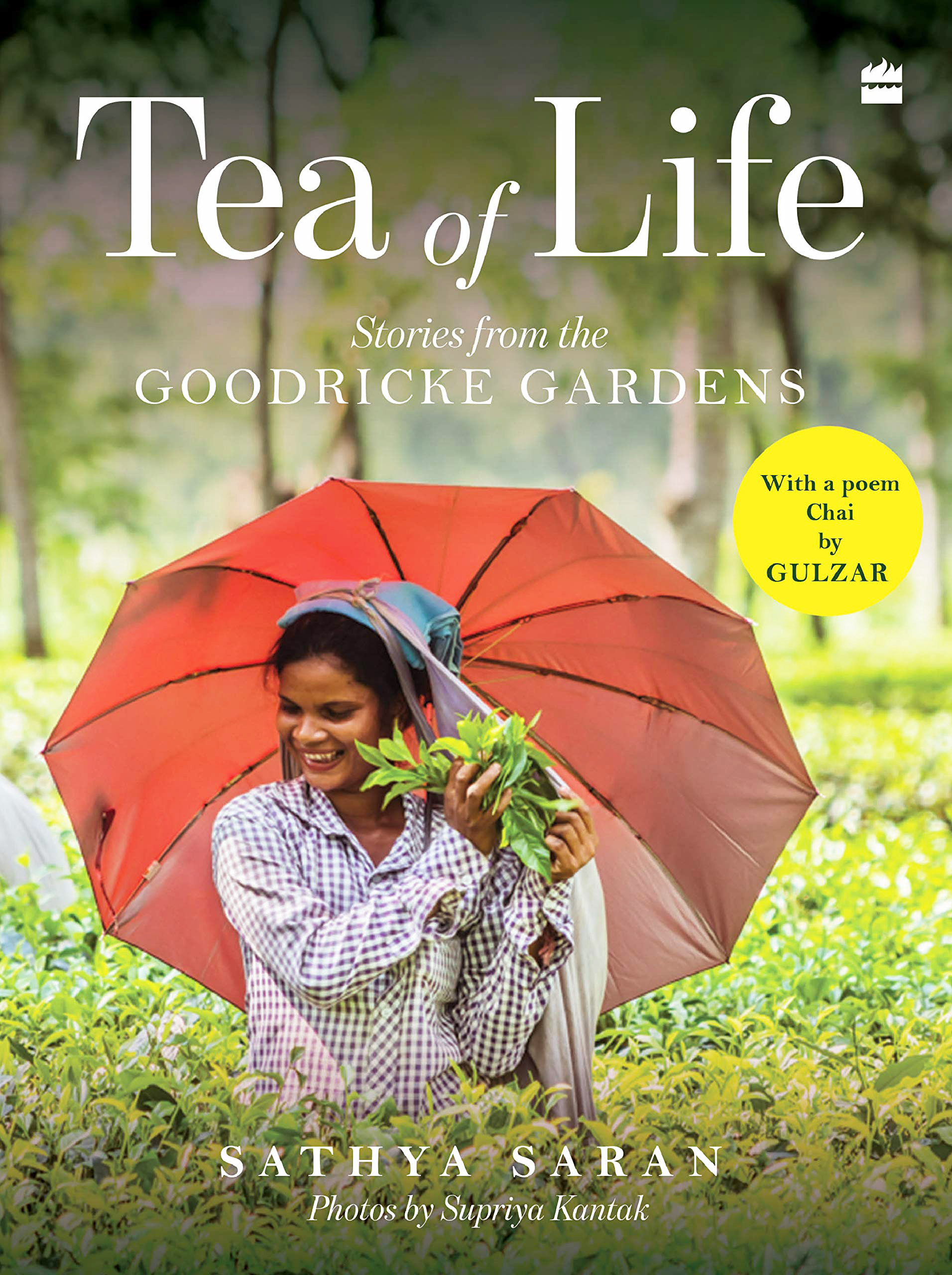

Tea of Life: Stories from the Goodricke Gardens

By Sathya Saran

HarperCollins India

pp. 208, Rs 599

Elephants are common sights across all the tea gardens of West Bengal and Assam, as the region is one of their natural habitats. As happens with agriculture, in setting up the tea gardens too, man has encroached on the spaces that were once the preserve of elephants. So it is but natural that they wander in and out, seeking to reclaim their space, or in search of food or water.

True to its philosophy of coexisting peacefully with the animal population that shares the regions Goodricke has its gardens in, the practice is thus to ensure the elephants come and go in peace. Their sightings are cause for alarm, but only action that warns the residents — both staff and labour — of animal movement, and which works towards preventing damage to life and limb, is taken.

‘Herds often come from the forest wilds into the gardens seeking shelter and water,’ according to Nigel D’Souza who, at the time of our visit, was the manager of the Nonaipara gardens in Assam. The area around his gardens is rich with wild life, and avid photographer D’Souza’s camera has captured Nilgai and spotted deer, barking deer as well as many species of birds and reptiles. This is his second term stint at the garden, and D’Souza is happy as he can add to the collection he and his photographer friend created during the first posting. ‘We have eighty-three species of butterflies,’ D’Souza said proudly.

Like most of the managers across the group, D’Souza is gung-ho about co-existing with animals and sharing the garden spaces with them in a mutual-benefit plan. Rampant deforestation during the Bodo agitation has robbed the animals of their natural habitat, depleting sources of food and water. The story is the same along all the gardens we visited in Assam. Many herds moved further north into the Bhutan hills, while others, like lost children, roam around, between the forest and the garden.

‘They find shelter in the forests within our gardens,’ D’Souza explained. ‘They come there, sometimes even give birth, and return. Have you ever seen an elephant herd escorting a new born into the forest?’ He asked excitedly, adding, ‘it is an amazing sight, the way the females surround and protect the calf as they move along.’

Taking the work of his predecessor forward, D’Souza is furthering a huge awareness programme among the labour to respect the animals and coexist peacefully with them through their comings and goings.

‘When you see an elephant, the natural instinct is to throw stones at it, and that in turn cause further conflict. In 2011, we had the highest record of human deaths due to elephants. We need to change the scenario, to save both man and animal, and I am working towards that.’

Setting up groups of activists is the first step. Forty-five per cent of the labour in the gardens under his care is Hindu, and ‘I am explaining the relationship of Ganesha to the elephant, and why it was chosen to portray the qualities of the gods.’ It is making a difference, he adds. ‘Earlier there would be damage to anything between 45 to 100 homes by elephants every year, now it has reduced to two or three.’

A rich brew of tea.

A rich brew of tea.

He has tracked the movement of elephants, and the corridors they take through the garden are clearly marked in words and visuals. Bright bougainvillea plants are planted along the corridors, they flower through the year and the labour knows now that the plants signify they are walking where elephants tread. So even if moving herds knock down the boards, they have an additional warning sign in the plants. ‘We have a no-interference policy. The animals usually come running into the garden, but once they are inside the gates they slow down and pad quietly along the roads, causing no harm to the tea plants, and enter the jungle areas. They seek out water holes in the jungle areas. Sometimes in the heat of summer, we find the waterholes running dry, and,’ he says, pointing out wet hollows in the rough ground beside the jeep we are taking a round in, ‘we create drinking holes and fill them with water.’

Often in the drains that run along the garden patches to run off excess water from the planted area, baby elephants get stuck. It causes a lot of furore, with rescue attempts by the older animals, and men adding their bit. To prevent such mishaps, the slopes into the drains have been made u-shaped from the traditional sharp v-shaped drop. Every little bit counts.

Recruiting from the labour and garden executives, a core committee of ten has been created of which the garden manager, regardless of who he is, is the president. The core committee includes tea pluckers. ‘We are formulating a plan of action and will slowly spread awareness across the gardens and villages. The plan is to include ten villages by next year, and keep widening the circle of awareness,’ he explains. And the move is to get the labour groups to take ownership of the programme, elect their leaders by rotation, and increase the number of such groups so each village has its own.’

Keeping a census of the elephant herds also helps. D’Souza has counted 235. ‘Twice a year, elephant herds combine, and the line stretches from the forest to half way across to the next garden of Orangajuli,’ he says.

Welcome the Maharaj

Of the many stories recounted by Lalit Sinha to sweeten the long and tiring drives from one garden in the Dooars to the next, this one is worth the retelling.

‘I was quite new in the gardens and shared a house with another young junior manager. One evening, as we were sitting inside, the watchman came to tell us that Maharaj had arrived. “Maharaj aya,” he said. I looked at my colleague somewhat intrigued, and he reassured me that it was a blessing to have the venerable sage visit us. “Call him in,” I said immediately, “let us make him welcome”. The watchman looked a bit taken aback. And my friend said, that is not how you do it. He handed me a spoon, and said, “you have to go outside and tap him gently with the spoon and invite him in”. Quite mystified, I took the spoon from him, and he signalled me to go out. I stepped out of the door to see a huge elephant standing there.

‘Rushing in, I told my friend, “there is an elephant outside.” He said, “I know, elephants are addressed as Maharaj here. So go and tap his flank with the spoon and ask him to go away, he will go peacefully.”

‘I went out again, holding the spoon outstretched in readiness. But the elephant was huge, and I lost my nerve and retreated inside. “I can’t do it,” I said, and my friend rolled on the bed with laughter. “Thank God you did not. Were you really planning it!” He exclaimed. Phew, I told myself, I had a narrow escape. Sometimes fear is a good thing.’

Forests in the Gardens

When the gardens were first created, forests were cleared, and the land made hospitable enough to nurture the tea plants that were planted in neat, endless rows. The plantations caused colonies of workers to settle within and around the periphery — pluckers, gardeners, and a host of other skilled and semi-skilled labour who came with their families to earn their livelihood working in the gardens.

‘Over the years the new settlements took their toll on the surrounding forests,’ says Subroto Sen, whose stately home is our refuge during our visit to Badamtam in the Darjeeling hills. The forests were an easy source of firewood for cooking and keeping warm, and the depletion was faster than nature’s capacity to renew the growth.

Over the years, in every garden, with sustainability as the ruling mantra, afforestation has been underway in an attempt to give back to nature what she has lost. Most gardens plant indigenous trees in the areas around, as well as within the gardens, and also demarcate areas where they grow trees for fuel. The fuel tree plantations are divided into sections, which are quickly replanted to ensure a regular supply. ‘When we cut down 5,000, we plant 10,000, but the long-term aim is to ensure all labour gets gas connections,’ Amar Singh Nain says.

In Badamtam, for one, this has already been achieved. Hundred per cent of the labour has gas connections. And all the fuel trees have grown to create forested areas, adding to the dense forests that have been planted around. ‘Actually, even from Barnesberg, you can see the thick forests here,’ we are told.

The garden rules strictly prohibit the uprooting or cutting of trees, whether indigenously grown or planted by man. The trees remain an important ally of the tea gardeners. They provide shade and protect the shrubs from too much sun even as they make plucking less taxing for the labour. But a balance needs to be carefully maintained.

On the first day of our visit to the Dooars, J.C. Pande, senior manager, Danguajhar, explained to us much of the delicate machinery that tea garden managers have to keep in motion between nature and man to ensure maximum output. As we drive around and sometimes walked through the narrow divisions between a one square of plants and the next, stopping to take pictures, Pande tells us about the interdependence between the trees and the plants. ‘While we need shade for the tea plants, we must ensure they don’t get too much shade,’ he says, adding that ideally, there should be around 40 per cent sunlight to keep bacterial and fungal contamination at bay. Too little shade will wither the plants, too much will cause other problems. He points to trees that have been marked. These, he explains, are giving more than the required amount of shade, and their branches will be logged off. Sometimes an entire tree may be cut, but that is only when it is absolutely necessary. ‘All of it requires regular monitoring,’ he says.

Tea Nursery and garden in Dooars (top); tea flower.

Little wonder then, to cover gardens that stretch across 900 or more hectares in some cases, managers, however senior, must take regular rounds. Most start at 5.30 or 6.00 as dawn turns to light, to return for breakfast. Subsequent rounds could be two or three in number.

As we accompany each of our hosts on their post-breakfast rounds, and again in the late afternoon before dusk falls, the real spirit of adventure each must carry in their hearts makes itself evident. The ride is not only gruelling on the mud roads, but also dusty and can be uncomfortably hot or cold, depending on the time of the year. The monsoons bring their own problems, turning the mud to slush, capable of stranding a vehicle. But come rain or shine, the tours around the garden are the only way the person in charge can ensure all is well. The labour, plants, animals and profits are all part of a manager’s duties, and the work never stops, 365 days a year.

Trees also play the role of sentinels, warning of pests that could harbour in their bark and pose a serious threat to the tea plantations. Each garden has devised its own way of setting up an alarm system against pests. Using stands or the trunks of the trees within the garden, planters wrap a sticky sheet and shine a light that mimics moonlight. Moths attracted to the light get caught in it. It is one way to be abreast of egg hatching time and be warned of caterpillar infestations. The strips of sticky material are usually blue or white. Red scares birds and so is never used.

(This excerpt from Tea of Life: Stories from the Goodricke Gardens by Sathya Saran was part of May 2021 issue, which was delayed due to the pandemic and released on August 3)

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated

Nice excerpt from the book. Anecdotes like Maharaja makes it interesting read. Enjoyed it throughout.

Dr. Vijay Sharma

Aug 5, 2021 at 08:40