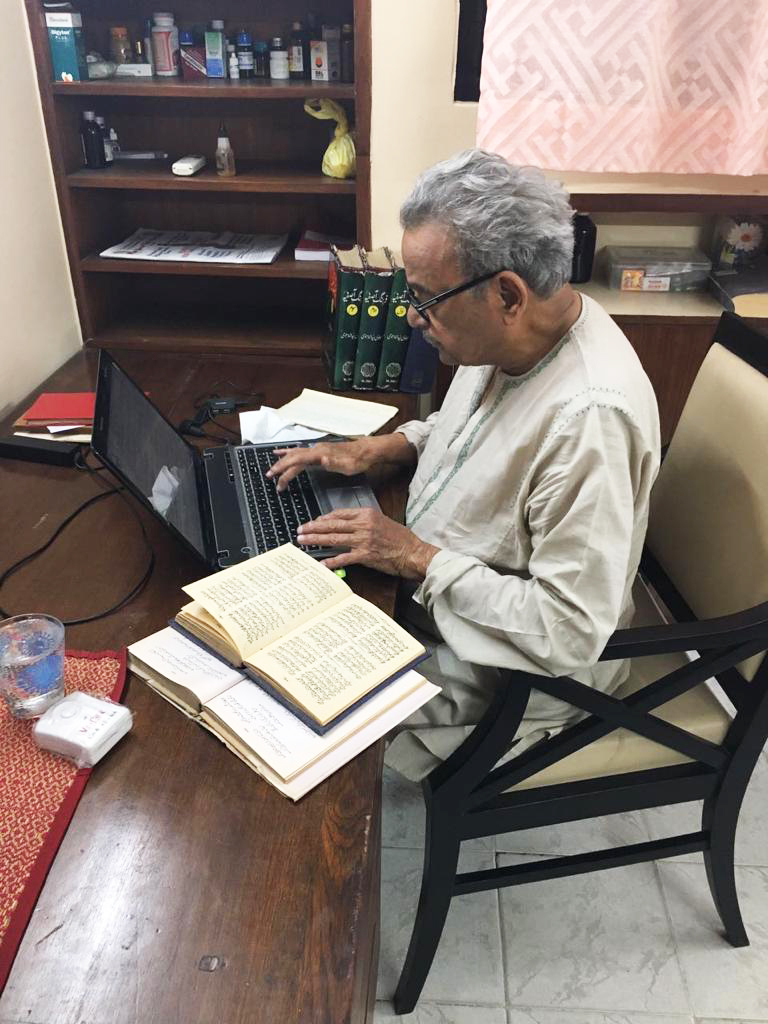

Shamsur Rahman Faruqi with Baran Farooqi. Photos courtesy: Baran Farooqi

Abba was the magician who introduced me to the wide and varied wonders of the world, taught me everything about life and its customs and kept me enamoured of his extraordinary personality. I was awe- struck by his learning, his cool, confident air and the way and adulation he commanded sat comfortably on his shoulders.

And may there be no sadness of farewell

When I embark;

Alfred Lord Tennyson

“Yeh meri akhiri bimari hai (this is my last illness),” spoke Abba with a wry smile on his face. He was addressing Dr Nandani Sharma, a homeopath in Shivalik, Malviya Nagar (New Delhi), whom we were all very fond of and trusted. That evening we had taken him there since he had expressed a desire to actually see her and not consult her over a video call to ask about the chances of curing the fungal infection which had invaded his eye during his stint at Fortis Escorts hospital where he had been hospitalised after having tested Covid positive. None of us had imagined that it was a matter of just a few days before he would be gone, transited peacefully and in full preparation of “seeing his pilot face to face.” Dr Nandani assured him that he still had long to live and accomplish some more as she was confident her medicines would be able to control the fungus. This conversation had taken place in her driveway as Abba was not able to walk since he had returned from hospital and so it was decided that instead of him having to go into her clinic, he would be seated on his wheelchair near the car and she would examine him. We returned upbeat from Dr Nandani’s place but it was as if Abba knew better than Dr Nandani this time. He had been sent the summons and he had answered them with acceptance and great sporting spirit. So, he laughed at our jokes in his weak strength and held out his hands or arms to embrace whenever he saw me or my sister or my daughters enter the room. He would kiss my hands and softly caress my head if he happened to be sitting, bolstered by the electrically operated bed we had arranged, half a dozen pillows and bolsters around him.

Of late, in fact, right from the time he would send voice notes from the hospital, he would often repeat, “I love you” or “know that I love you.” Of course, we had never had any doubts about this ever because Abba was the master of expression. A vocal person, he taught me how I need to say “thank you” even to my own parents if they got me something and to house helps and friends for services rendered or acts of kindness. I once overheard him reproaching my mother for never doing salam to him first when he got home from office or smilingly extending her hand of welcome. Always cheerful and smiling when he came home from office, he expected everyone else at home to be as smiling and welcoming as he was. Each time any of us would enter his room for something, he would beam aaiye aaiye (do come in) and show his pleasure. He used to call me “funny face” sometimes, which didn’t seem very amusing to me but I knew I was supposed to show a sense of humour and not sulk over little things. I finally asked him one day, “Why do you call me funny?” He answered that funny faces are those who are delightful and make him feel happy and full of mirth. Once, when I made him fill out my columns of questions like, who is your best friend, what’s your favourite colour, what are you scared of and so on, (this was a raging activity in my school those days that you took autographs of people in your autograph book for no reason and also made them fill columns which were made in a double page of a register.) I remember almost all his answers to this day but I’ll speak of only a couple, to the question, “If you had a wishing wand, what would you wish me to be?” he had answered “Queen of Sheba.” I immediately understood this is something divinely great and luminous and so on, since I didn’t really know who queen of Sheba was at that time. In the answer to the question, “what are you scared of?” he had answered “centipedes,” making me aware that he was human and vulnerable in his own way.

I have wandered far from what I was initially talking about — his illness and his demeanour during those days. After stretching out his hands and making me sit close, he told me one day that the time for him to leave this world had come and that I should allow him to go. That the ceaseless struggle that we were putting up to withhold him was futile and he was convinced about his departure. He needed to go back to his spacious and open house where his favourite pet dog Bholi and others were, and he wanted the birds to sing near his window before he ceased to breathe. On those nights when he was awake and not faint with weakness, I would sit by him and read out his WhatsApp messages to him and also make him listen to the voice notes people had sent. He chose to respond to one or two voice notes or emails and messages every day. He would speak the voice notes himself and dictate the written messages or emails. He once made me write a mail to CM Naim sahib though there wasn’t one from him that day and also to Frances Pritchett, informing them about his health. One of the voice notes that he sent to Amin Akhtar (a relative of ours who has been assisting him in his library-cum-office and miscellaneous affairs for many years) was about the local graveyard which Abba’s efforts had helped restore and put in order after his return to Allahabad after retirement. He asked Amin to go to my mother’s grave and convey his salam there. He also asked Amin to see if it was still possible if he could be laid to rest right next to her, but in case anyone objected, he reminded Amin, he had chosen a remote corner of the graveyard for himself as a second choice. Amin responded next day tearfully that he had carried out his instructions and that there was no question of anyone objecting to his burial next to his wife. He had written the ayat he would like to be written on his tombstone and given it to Amin many years back already. I felt heart-broken at these conversations but I, too, knew that they must happen and not be left unfinished, for the day of parting may come if it had to, and there was nothing anyone would be able to do about it.

I marvel at Faruqi’s (as he would like to refer to himself, sometimes even calling himself “saala Faruqi” or “Fraudie”), courage and foresight for the way he bore his illness. He was also very kind and forbearing towards us, always succumbing to our pleas for making him eat or drink something despite being terribly averse to both ideas. Every time he would ask when we were planning to go back to Allahabad with him, and my sister or I would give a date a week or two away, he would nod patiently and agree. Ever since Ammi passed away, Abba had been careful to hand over all that she had left behind as money or property to both of us, saying this belongs to you both as she was your mother. But when it came to caring for us and endowing us with gifts or maintaining the large house, he acted as the perfect father. Never once did he ask us to bear any financial burden of any kind, be it the property Ammi left behind — he continued to pay property tax for it — or other charities that she was used to doing at her native village.

Unselfish by nature, and generous towards the world and its people, he once told me that he had spent his life with the aim to be of help to any number of human beings he came across in the journey of his life, particularly during his career in civil service. I have never known or seen, nor do I ever hope to see, another more good-hearted person who is also competent, capable and one of the greatest literary minds of the century. Abba loved exploring new things and enjoy them if the children so wanted. Any new joke, and we wanted to share it with him, a new piece of machinery or a gadget and he would be curious to know about it, any adventurous outing, and he would want to be a part of it. In fact, most of the interesting outings in my and my daughters’ lives were either planned by him or planned for him. It was just last winter that we all went to Kochi together to explore the backwaters of Kerala and spend some part of winter there to avoid the low temperatures up North. As he grew older, he had begun dreading the winters, as they confined him to his room and restricted his hours in the study. There were arrangements to keep his room, his study, and even his bathroom warm, but the cold got to him since he was finicky about wearing “inners” and heavy quilts bothered his frail body with their weight.

Apart from travelling to new places and exploring places of historical interest or natural beauty, Abba had a penchant for stylish and tasteful clothes and good food (which he always ate very little of, but wanted to be served in good quantity). However, he had this little thing in his head about what are supposedly “manly” dishes and which foods are meant to be consumed only by women. Consequently, I never saw him relishing anything even slightly sour. He was supremely dismissive of achar and chutneys or chaat of any kind. Even remotely foul-smelling vegetables were banned in our house, not to speak of home-made sirka or ghee being extracted from malai. I once witnessed a bitter exchange he had with my mother for having gotten mooli achar prepared in the courtyard of our house. This was even worse than cooking sabzi out of the mooli! Like any other subversive spouse, Ammi would sneak such things into the house and eat them secretly when he was in office.

Abba was a great animal lover, too. As children, having animals and birds around us was as natural as breathing and it must never have occurred to us that in the eyes of the world, we qualified as “animal lovers.” At any given time in our lives, there were always dogs, cats, turtles, mynahs, peacock chicks or grown peacocks, pigeons, partridges, quails and finches and other singing birds. Abba would often send a tid-bit or two to his pets (I said “send” because the house was really so huge in area that things had to be delivered from one place to another) and tell the person he had chosen for the task, “greet him with my salam and say that Faruqi sahib has sent this. We knew a lot about birds, which ones could be tamed or caged and which couldn’t be bred in captivity. He also had a collection of coffee-table type books on birds and animals and some of the exciting times of my childhood were certainly made of browsing through those books. Sea creatures like starfish, octopus or dolphins intrigued me greatly and I was enamoured by pictures of the mighty ocean. I longed for a trip to a coastal town but my wish was deferred for quite some time as my parents had already been to places like Bombay and Calcutta many times and were more focussed on the hills or animal and bird sanctuaries.

Abba played his favourite musical records of ghazals and classical ragas in the mornings which were spent enjoying three to four cups of bed tea. The tea, which would be brewed in an elegant tea pot and had a bitter aroma, would cool gradually as he read the morning papers. The music would continue to play up until he was almost ready for breakfast. Gradually though, I, too, developed a taste for singers like Farida Khanum, Iqbal Bano, Mehdi Hassan, Kishori Amonkar, and artists like Hari Prasad Chaurasiya, Ustad Bismillah Khan and other such maestros. My sister and I were also subjected to regular doses of mushairas and seminars which we had to duly attend along with our parents; I was still wearing frocks at that time. By the time I grew up, I had sat on the laps of many a great Urdu writer, poet or artist. I grew particularly familiar with Naiyer chacha (Naiyer Masud), Shamim chacha (Shamim Hanfi), Shahryar chacha and Balraj Komal uncle. The critic Khalil-ur-Rahman Azmi was someone I don’t clearly remember but I recall Abba grieving over him so much that Ammi had to chide him about moping a couple of times.

Abba was the magician who introduced me to the wide and varied wonders of the world, taught me everything about life and its customs and kept me enamoured of his extraordinary personality. I was awe- struck by his learning, his cool, confident air and the way and adulation he commanded sat comfortably on his shoulders. He lived a life of grace and élan. Once, when on one of our usual summer holiday road trips, when we were touring Uttar Pradesh and Himachal, there was an incident which impacted me for the rest of my life. It so happened that the road we were on was broken severely, blocked, you may say, so Abba decided to take a detour through another path, which was on the lower side of the road, beside the fields. It was a water-logged path but he estimated that our Ambassador car would be able to successfully wade through it. But to our chagrin, the car got stuck in the slush beneath and water began to enter the car at a high speed! The car seemed to be floating in the water, I began to bawl loudly saying, “Hum doob jayenge, hum doob jayenge, (I’m going to drown, I’m going to drown).” I got one of the most unexpected and loud scoldings of my life from him at that time, “Abey tu apne liye ro rahi hai sirf! Aur baqi tere ma baap aur behen? (Stop crying and saying such a selfish thing! Why are you worried about only yourself drowning and not your parents and your sister?)”. I wiped my eyes and looked at him, bewildered. It was a lesson I have remembered to this day — unselfishness and courage.

So close, so friendly and participative and yet so distinguished and awe-inspiring! They don’t make men like you any longer, Abba. I conclude my piece again from the poem quoted above. Abba would sometimes teach us English poetry, too, apart from Urdu and Persian. Abba had read out the poem to me many, many years ago and explained it to me. Alfred Lord Tennyson’s “Crossing the Bar” was one of his top favourite poems of the English language. I remember his voice almost choking at the sombre grandeur and sonority of the poem:

For tho’ from out our bourne of Time and Place

The flood may bear me far,

I hope to see my Pilot face to face

When I have crost the bar.

Perhaps, the very same lines were echoing in his mind when he breathed his last, in full control of his senses, aware and courageously ready for the journey across.

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated