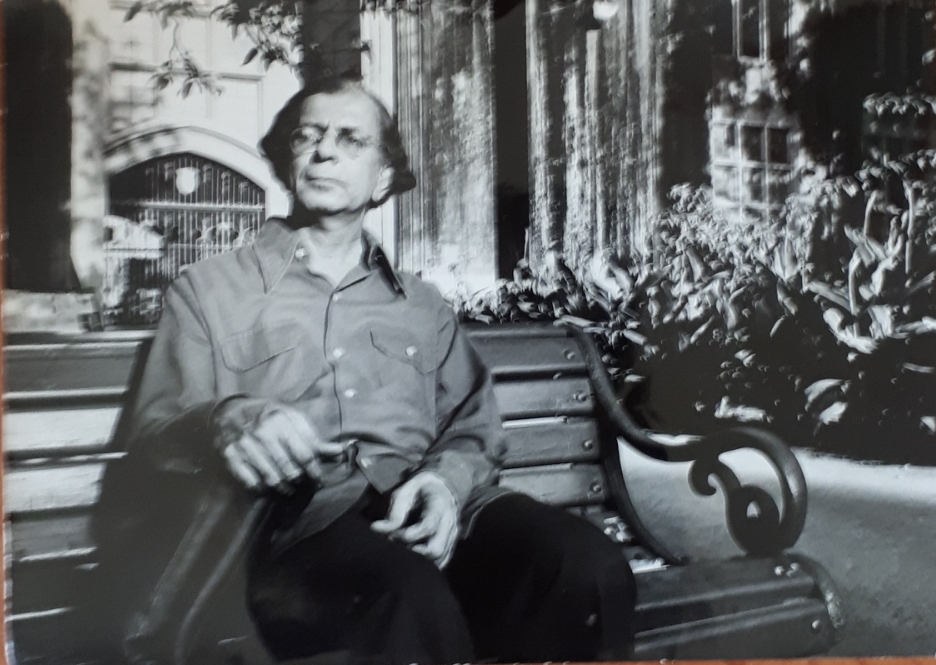

Nissim Ezekiel (1924-2004). Photo courtesy of Kavita Ezekiel Mendonca

Kavita Ezekiel Mendonca reflects on the life and legacy of her father, Nissim Ezekiel, the Father of post-colonial Indian writing in English, whose birth centenary is being celebrated this year. An unworldly man deeply devoted to poetry and teaching, he lived simply, with minimal needs, but had a generous heart, giving freely to others

If I could pray, the gist of my

Demanding would be simply this:

Quietude. The ordered mind.

Erasure of the inner lie,

And only love in every kiss.

(Lines from Prayer 1 by Nissim Ezekiel)

My father Nissim Ezekiel (1924-2004), poet, editor, professor, playwright, art, and television critic, was born in 1924 into a Bene Israel Indian Jewish family. By common consensus, he was affectionately known as the Father of post-colonial Indian writing in English, specifically in the field of poetry. He passed away at the age of 79, in 2004. He wrote hundreds of book reviews and essays on poetry, travelling extensively in India and overseas on invitation, reading his poetry and speaking at various literary events. He was invited as Visiting Professor at the University of Leeds in 1964 and Writer-in-Residence at the University of Singapore.

Tragically, he died from Alzheimer’s, from which he had suffered for the last several years of his life. People often ask me why such a brilliant mind (their words) was afflicted by this debilitating illness. Alzheimer’s does not distinguish between individuals. Sadly, it can affect anyone, poet, singer, or king, with no logical explanation. Like cancer, or the untimely death of a child, we don’t get to ask why this debilitating disease must be endured by a cherished family member.

This year, we celebrate his birth centenary and seminars and presentations have been held in his honour by a college in New Delhi and by the Sahitya Akademi, with more to follow. I have had the privilege of speaking about him, and doing an interview about him as my father, admitting easily that he was an indulgent father, and about other professional aspects of his work. A book to commemorate the occasion titled ‘Nissim Ezekiel Poet & Father’ compiled by me, edited by Vinita Agrawal, and published by Pippa Rann Books and Media, is to be released shortly.

My father was an unworldly and impractical man with his “feet firmly planted in the air” as I have described him in one of my poems. He was a man of few needs and a voracious reader. Our home was littered with books and magazines, which, for lack of space, sometimes had to be shared with our clothes cupboards. A battle with silver fish would ensue and the silver fish were inevitably declared the winners! He was a great storyteller and had us in splits when he narrated his travel experiences. He was the Founding Editor of Quest magazine in 1954 and sub-editor of The Illustrated Weekly of India, on his return from London. He was also invited to edit Imprint magazine run by the Hales from their home. My father loved going there as the little daughter who was just a toddler then, would announce his arrival by clapping her hands and squealing “Nissum come, Nissum come.!” She called him Nissum and the sheer delight with which she welcomed him gladdened his heart. His eyes twinkled when he told us that story, imitating her perfectly.

His passion was writing and teaching. Poetry was at the front and centre of his life, as he himself confessed in interviews. He gave his money freely to publishing poetry and social causes. He declined lucrative jobs though it would have helped his family. When asked for the reason his response was “If I accept this job when will I get time to write.?’’ When offered the job of Vice-Chancellor of Poona University, his response was “I don’t want to leave Bombay.” His love of the city of his birth with all its challenges, was reflected in many of the poems he wrote. It was the same response when I invited him to live with us in Mussoorie, where I held a job teaching English at an international school. He was aging and needed care, which he reluctantly admitted, but he adamantly refused to leave Bombay.

Nissim Ezekiel’s gravestone

About the time he turned 50, he decided to become vegetarian. His meals were simple, sometimes even ketchup and rice, if nothing else was available. During working days, he ate at the ‘Sanman Hotel’, a vegetarian restaurant which was located opposite the P.E.N Centre where he worked. His favourite food was the south Indian dish Bisi Bele Bhath, a flavorful dish of rice, lentils, and vegetables. At the P.E.N. centre, he was seen surrounded by younger poets to whom he generously gave his time, teaching them the craft of poetry and working on their manuscripts. His desk and the shelves were cluttered with books, journals, and manuscripts. Some of his critics called the place untidy, little realising that if he spent time tidying up, he might have had less time to spend more time with them. In any case, one thing he knew for certain; poets and their poetry trumped housekeeping.

My father believed in moderation in all aspects of life (except... Poetry!!) and practised frugality in his personal use of resources most of us would not think of economising on, or reflecting in how our excess would affect others, those less fortunate, whether it was in the use of water, electricity or food. He was always thinking of others who may not have had as much access to the basic necessities of life. He was a man who was outwardly focused. He was health conscious and, apart from taking long walks from our home by the sea, insisted on walking up the stairs to the fourth floor at the Theosophy Hall, when he had meetings with Madame Sophia Wadia. We once caught him jogging in the long passageway outside our bedroom at my grandmother’s house!

My father kept a diary for his appointments and was meticulous about punctuality and not keeping people waiting, even to the extent of arriving twenty minutes early for a dinner engagement, something which exasperated my mother, who had to manage her domestic obligations before setting out with him to dinner parties.

At night, long after all the day’s work had been done, I could hear the creak of the old wooden stairs at 11 PM... his voice still rings in my ear. “Kavitam!” and I would know that he was home. His day was far from over. I’d see the lights in his room sometimes at 3:30 AM. I would make my way to his room, knock, and call out, “Daddy, it’s late. You should get some sleep.” Sleep or not, he was at the P.E.N office by 9 AM. Sharp! He took the train from Bombay Central to Churchgate after a fifteen-minute walk down broken sidewalks from my grandmother’s home where he lived. He never complained about anything, whether it was too hot, the train too crowded, or whether there was a caterpillar in his food at a restaurant one day! He turned to a friend who happened to be seated at a table nearby and exclaimed “That must have been one very hungry caterpillar!” I promptly bought the children’s book with the same name by Eric Carle. It is now one of the most beloved books on my shelf!

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated