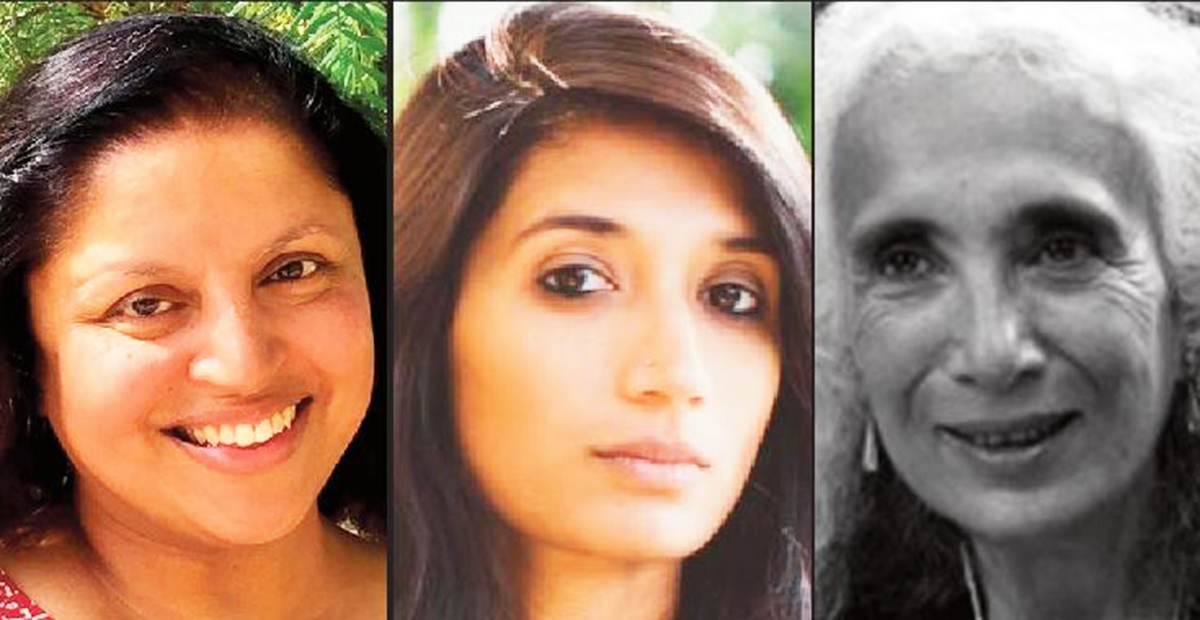

Devi S. Laskar, Madhuri Vijay and Tova Reich have all been longlisted for the DSC Prize for South Asian Literature

Most of the South Asian novels are about gender oppression, cultural and religious biases, and mostly about growing up as a minority. The second generation immigrants are still struggling with the remnants of these biases.

I am intrigued by the increasing number of entries by women writers for the DSC Prize for South Asian Literature. It is great that more women voices are being heard and the stories that they are writing are very inspiring and often become role models for women in similar circumstances. There is this beautiful review of South Asian writing by a UK-based blogger who said that “having been born and brought up here I had no idea that there was South Asian writing by people like me. I found that I had had similar experiences as someone else which was empowering for me."

These writings have a two-fold impact. If you are from South Asia and live in a South Asian country, then these writings can be empowering, but if you live in the West then reading South Asian literature can also affect you in a different manner. Having lived in England for the past thirty years, I find that most of the South Asian novels are about gender oppression, cultural and religious biases, and mostly about growing up as a minority. The second generation immigrants are still struggling with the remnants of these biases.

These biases are often fed by the culture that we import with us. Culture out of context is seen by the younger generation as oppressive and is often mentioned in their writing. Some of the commonly encountered repressive practices are being brought over as baggage from the East.

Let’s look at some of the cultural practices and their meanings. Often designed to meet the local needs of the population, these practices took various forms, for example, prayers commonly used to hail the seasons and harvests, and avert droughts in the region. Some practices were prevalent to subjugate women, others like female genital mutilation (FGM) and child marriage had a basis in keeping female sexuality under control. The relationship between a man and a woman was often portrayed as the man being stronger and more privileged. This relationship was imbibed from our childhood from watching our parents, films, public behaviour, posters, and all the mythological stories. Every woman in every epic has been defended for her actions often by other women. “Sita was very strong and in order to punish Ram she decided to be swallowed by the earth”. No one mentions that Ram was not right for suspecting his wife.

Somehow the myth of the power of men continues in the western narrative. We as mothers insist that our daughters’ lives are incomplete without marriage. Many other practices are led by us, brought over from the East. A case in point is the karva chauth fast, a fast kept by women for the long lives of their husbands. This fast is glamourised by Indian women in Chicago, London and in many countries in the West as if this was the most empowering event in their lives. Women in their fifties, now the second generation immigrants who were the flower power children, are not very different from their mothers by sticking to their culture after having abandoned it in their youth.

The writings by women from South Asia often talk about their partners’ oppressive behaviour, which is often romanticised with words like sacrifice and redemption. I was writing about the society we live in and a British woman looked at it and said I have no respect for the women who tolerate their husbands cheating and take so much crap in their lives even when they live in the West. That started my quest for finding out whether the word sacrifice was good for us or did it make our lives miserable in the end. I loved old Hindi songs and they perpetuate the sacrificing woman. Listen to English rap and the women are calling out cheating men.

My question is, when will we truly understand the importance of equality in every field of life? Why are we such hypocrites? We want equality but don’t want to give up our oppressive cultural practices. There is a very common narrative in a number of South Asian films and writings where the child brought up with western values, often a girl, has to go back and marry someone from the country of her origin. It will always be the woman, mostly the mother, who will equally participate in this repatriation. No one wants to shake the status quo.

I have often questioned politicians in Britain, asking them the difference in the law of the land and the prevalent South Asian cultural practices. Their vote banks in these countries surprisingly are also the mosque and temple-going masses who want to continue stopping women from entering the inner sanctums of these places, even when they are located in a land which prohibits such acts. In the guise of culture, such practices have been brought over and all the work done for gender equality by women over many years has come to nothing when it comes to saving the eastern women from gender biases. The South Asian woman writers have to take their new context into consideration when romanticising the ills of our culture and society.

“The use of controllable, limited, stereotypical visual and other representations is counter-productive to evolving and fully integrating the South Asian literary identity into the world literary canon,” says Dania Zafar, who is an MA Publishing graduate from Kingston University and a graphic designer. Her mission is to create inter-cultural dialogue and promote cultural understanding through publishing. Readers in her study use “South Asian diasporic literatures to negotiate various ethno-religious obligations, national origins, gendered expectations, regional affiliations, and histories of immigration. Gender, particularly the policing of femininity and women’s sexuality, are key facets in how the South Asian American community asserts a public image of exoticised ethnic authenticity and in how we recognise ourselves and each other as conforming to these expectations.”

When we began the DSC Prize for South Asian Literature, I was all fired up because I was so keen that someone should explain to the people I now live with, in England, who we are and where we come from and what makes us the people we are. Over the eight years of the prize and the growth in my own understanding, I have begun to question the validity of a culture which oppresses women and is transported into another country which is far more advanced in gender equality. Are we perpetuating it and validating it with our writing or questioning it and sharing it with a non-Asian reader? Does our literature inform them or suggest to them that it is okay to keep these women out of temples and other places and deny them an equal space. I am not sure because of the dialogues I have had with many politicians in England who keep saying “but we need to respect the culture, therefore, we have to respect the fact that their cultural practices allow child marriage, FGM, triple talaq and stopping women from entering the inner sanctums of religious places”. It has taken many governments and NGOs in this country working with them to ban child marriage and FGM making it illegal here. I think much more work needs to be done to explain culture and context through our writings. It is a great start but to take out these age old understanding of traditional spaces women occupied in our culture, even by us women who were brought up in India, is going to take time and possibly another generation of writers and NGOs.

Zafar also talks about South Asian literature being “a model of reading that addresses the complexity of the various national contexts and gendered hierarchies that discretely, covalently, and historically influence this diasporic community’s formation.” Looking at the longlist for the DSC Prize 2019, I am heartened to see voices of women that have tried to deconstruct the South Asian cultural nuances and present it in a more global and meaningfully relevant perspective.

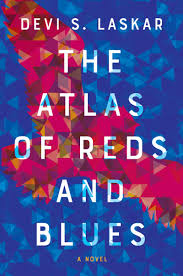

Devi Laskar’s debut novel The Atlas of Reds and Blues vividly brings alive the struggles and complexities of being a South Asian woman and a mother to daughters in today’s America. The narrative forces us to look at issues related to identity and culture in a cross-national societal landscape. Similarly, The Far Field by Madhuri Vijay explores nuances of Indian life, cultural biases and sexuality through the perspective of an outsider. While being a personal story rooted in tradition, it highlights the importance of cultural context for analyzing and interpreting why people lead the lives that they lead.

The protagonist in Sadia Abbas’s An Empty Room faces the identity struggle of a woman artist who after marriage is suddenly ushered into an environment of stifling conformity. The story is set at an important time of the nation’s history where women have to find creative solutions in a hostile environment to resolve their own dilemmas. A complete outsider yet incisive perspective on South Asian life is presented in American author Tova Reich’s latest novel Mother India which explores the complex societal constraints of a modern India as it evolves over time.

The traditions, complexities and dysfunctionalities of a rapidly globalizing South Asia as described in the literature above can become empowering or used to subjugate women further. Women writers from this region need to look at its western readers and not only inform them but condemn such practices as archaic and out of context.

Editor’s Note: The longlist for the DSC Prize for South Asian Literature include:

• Akil Kumarasamy: Half Gods (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, USA)

• Amitabha Bagchi: Half the Night is Gone (Juggernaut Books, India)

• Devi S. Laskar: The Atlas of Reds and Blues (Counterpoint Press, USA)

• Fatima Bhutto: The Runaways (Viking, Penguin Random House, India, and Viking, Penguin Random House, UK)

• Jamil Jan Kochai: 99 Nights in Logar (Bloomsbury Circus, Bloomsbury, India & UK, and Viking, Penguin Random House, USA)

• Madhuri Vijay: The Far Field (Grove Press, Grove Atlantic, USA)

• Manoranjan Byapari: There’s Gunpowder in the Air (Translated by Arunava Sinha, Eka, Amazon Westland, India)

• Mirza Waheed: Tell Her Everything (Context, Amazon Westland, India)

• Nadeem Zaman: In the Time of the Others (Picador, Pan Macmillan, India)

• Perumal Murugan: A Lonely Harvest (Translated by Aniruddhan Vasudevan, Penguin Books, Penguin Random House, India)

• Raj Kamal Jha: The City and the Sea (Hamish Hamilton, Penguin Random House, India)

• Sadia Abbas: The Empty Room (Zubaan Publishers, India)

• Shubhangi Swarup: Latitudes of Longing (HarperCollins, HarperCollins, India)

• T. D. Ramakrishnan: Sugandhi alias Andal Devanayaki (Translated by Priya K. Nair, Harper Perennial, HarperCollins, India)

• Tova Reich: Mother India (Macmillan, Pan Macmillan, India)

The shortlist for the DSC Prize for South Asian Literature include:

• Amitabha Bagchi: Half the Night is Gone (Juggernaut Books, India)

• Jamil Jan Kochai: 99 Nights in Logar (Bloomsbury Circus, Bloomsbury, India & UK, and Viking, Penguin Random House, USA)

• Madhuri Vijay: The Far Field (Grove Press, Grove Atlantic, USA)

• Manoranjan Byapari: There’s Gunpowder in the Air (Translated by Arunava Sinha, Eka, Amazon Westland, India)

• Raj Kamal Jha: The City and the Sea (Hamish Hamilton, Penguin Random House, India)

• Sadia Abbas: The Empty Room (Zubaan Publishers, India)

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated