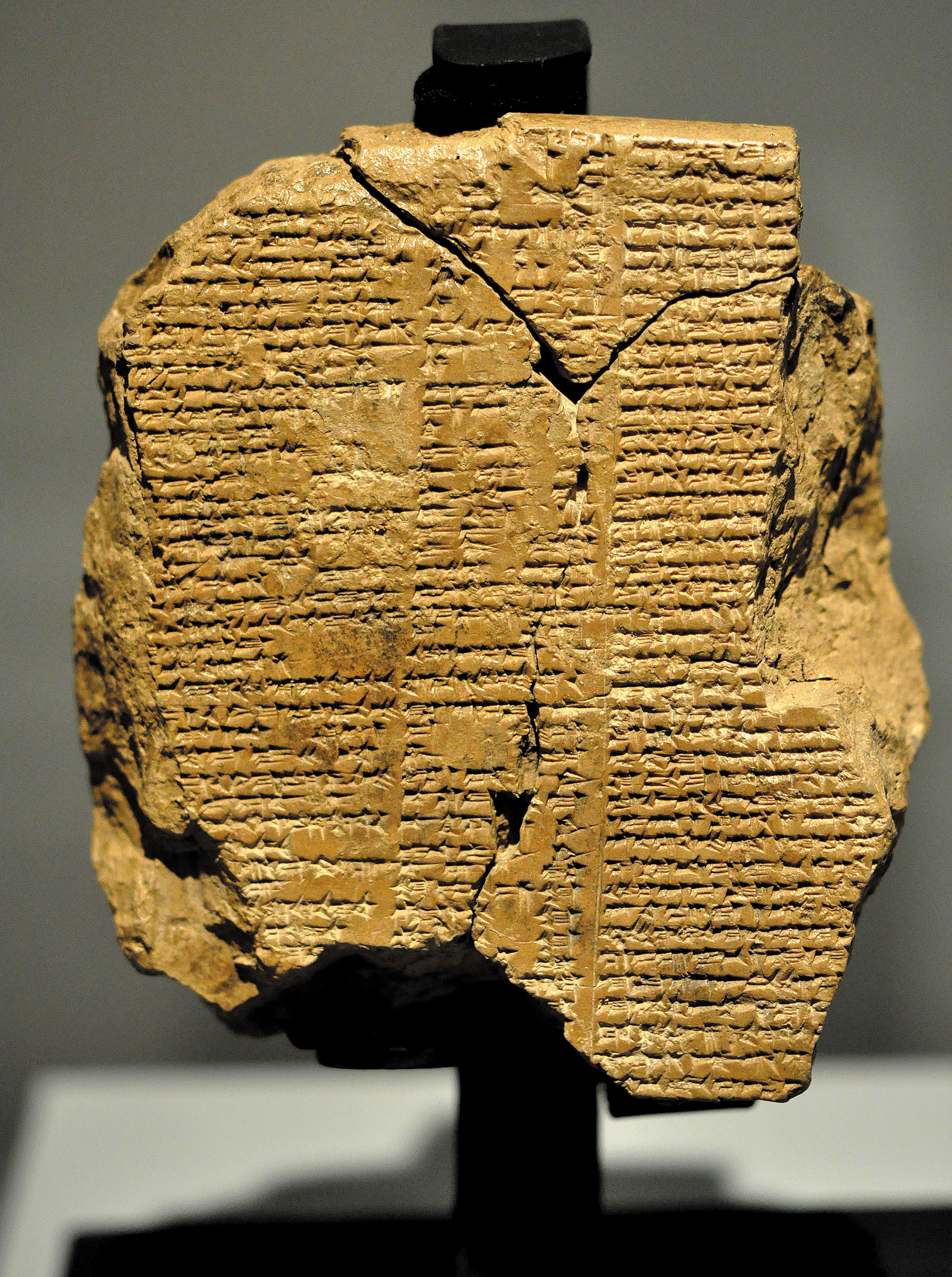

Tablet V of the Epic of Gilgamesh. The Sulaymaniyah Museum, Iraq. Photo: Wikipedia Commons

Extracts from Gilgamesh Retold

The earliest written stories from which the Mesopotamian Epic of Gilgamesh spring date from the Third Dynasty of Ur (circa 2100 BC). They inspired the later, eleven tablet version, collated by the priest/scribe/poet Sin-lique-Uninni in around 1200 BC. Written in cuneiform on hundreds of clay tablets found by Victorian archaeologists in the buried library of King Ashurbanipal (circa 650 BC) it is often regarded as the first great work of world literature. About a king who oppresses his people until the gods send him a friend, the wild man Enkidu, to teach him about love, humility and the responsibilities of kings, the story is as relevant today as when it was first written. These extracts are from a complete new, fifteen-chapter version, by Jenny Lewis, some of which has been translated into Arabic by Adnan al-Sayegh and Ruba Abughaida, performed at the British Museum, the Ashmolaen Museum, Oxford and several international festivals. ‘The Flood’ episode was exhibited as part of a collaboration with the British artist and printmaker, Frances Kiernan, at Salam House, London and at the Iraqi Embassy in April 2017, with an accompanying chapbook published by Mulfran Press.

Chapter 12

Gilgamesh at the Edge of the World

Consumed by grief after Enkidu’s death, Gilgamesh wanders in the wilderness until he

reaches the Edge of the World where he comes to a tavern kept by the demi-goddess, Siduri

Shrouded in hoods and veils she lived alone

At the sea’s edge beside the salty spray

And she was tough as wind-blown marram grass

Whose roots creep craftily beneath the dunes

And bind themselves to knot the flying sand.

Her dishes, racks and cups were solid gold

Her wine and beer was casked and kept in gold

Her tavern only visited by gods.

She saw him coming from a long way off,

At first a speck, a spot, a moving dot

But closer up she saw he was a man

So trouble-scarred, a leather sheath of bones

His face a pitted shield of dents and hacks

That life had dealt him, or the stony world.

As he drew near she ran to bolt her gate

With shackled breath, her chest a tightened strap

Of terror as she climbed up on her roof.

‘You! Woman! Open up!’ his shout was rough

She gave back words to him in eme-sal

‘First tell me who you are and why you’re here

And why you batter rudely at my door?’

With this soft speech she tamed his seething wrath

He dragged his fingers through his matted hair

And writhing in his woe he told his tale.

When she had heard it, she held out her hand

And led him to her table straight away

And sat him down and gave him beer and bread

And spoke to him as she would any king.

‘The path you’ve come is far yet it must stop

As every other’s must, except the gods’,

Deep in the earth’s loamed bed where you will sleep

And tread the dream-road to its bitter end.’

At this the listener’s tears began to stream

Like hares across a field in wintry sun.

Siduri spoke once more and took his hand —

‘Your wife and children wait for you at home

Be wise! Go back again to Uruk’s fold —

Among your kindred you’ll find warmth of heart

Is worth more than a thousand precious rings

And love, not battle glory, life’s great gift.’

Chapter 13

Meeting Uta-Napishtim The Flood Survivor

At last Gilgamesh finds Uta-napishtim who survived the Flood hundreds of years earlier.

Gilgamesh begs him for the secret of immortality but Uta-napishtim points out the

Gilgamesh begs him for the secret of immortality but Uta-napishtim points out the

disadvantages of living forever.

He said ‘When Enlil sent the mighty Flood

Ea came to me one night to warn me first

to make a vessel huge, of cedar wood

then gather seed of all that came from earth

each plant and bush, each tree, each bird that flies

each creature that is able to give birth

and bring them to the ark for sanctuary.

I toiled to finish well before the storm,

so when the tempest howled across the sky

and people cried as they began to drown,

the river rose to swallow all in sight

except my craft which floated, light as down.

Even the gods and goddesses took fright

and lay curled on the ground in sheeting rain

as dogs forsaken by their owners might

who wait to hear their name, yet wait in vain.

The sea became a city of the dead

and fishes made the forests their terrain

each cedar branch with moonstone scales inlaid

each date palm grove a giant bed for whales

each mountain peak a rock beneath the waves.

Six days and nights the violent typhoon raged,

then on the seventh, all was motionless,

the warrior winds of Shamash had been caged.

As Aya’s peaceful light flooded the skies

we held the deck rail, breathless, as we gazed

in silence on a mirrored paradise.

Near to Mount Nimrush now we castaways

waited for sinking waters to reveal

the slopes of mountains or some solid place

where we could disembark our crew of souls.

A dove flew out but then returned again,

a swallow also flew back to the fold:

but when I set the raven free it went

bobbing and bowing on its patch of land,

finding once more its source of nourishment.

As the waters drained away we found

no humans left on earth except for us;

we had escaped the fate Enlil had planned.

So Aruru gave us this new status —

alone of humankind to be immortal —

and how we long for this to be reversed:

to be allowed to pass through that same portal

that you so dread, my friend, that you so dread;

who wants eternal life when flesh is frail?

Silver Oak

instead of heat and light

grey shrouds

each morning a burial

we fight our way out of:

your sentinel stillness

seen through muslin

would look at home

in snow-covered tundra,

among the herds

and ice-lapped edges:

yet this is India too,

her private winter face

cleansed and secretive

in her dressing table mirror

with thoughts of spring

a world turned away from —

waiting for reflections

on a silver bark.

Maker

for Pedro Bosch

this is the place where broken

things come to rest from their brokenness

they can’t get the taste of terracotta

out of their mouths

they know they came from mud —

only yesterday

they were a substance

to be walked on

now their bridles, wings, trunks

hold unexplained shadows

the moon

eyes the world from their jagged holes

above them, peacocks roost in the trees —

Neem, Arjuna and the Banyan

under which Krishna sat

scooping butter

the bark’s twisted textures

are ropes going into the earth

resting before the spring burst

of growth, green after green

reaching for the sky with its

shattering light.

Tribute

They made shields from themselves, a phalanx of bony mantles

we crushed as we stepped ashore: clams, cockles, whelks — oysters

that changed from male to female over a hundred tides.

Then those women with their blue-veined forearms flung back

against the pebbles, not understanding us — their men off fighting

somewhere behind the hills, lost in perpetual drizzle and cloud.

All we wanted was comfort, but they showed us no compliance,

instead, they shut their ears to the foreign sounds we made,

white ears more delicate than shells, with tiny, labyrinthine cochleas.

They were less impressive than African bounty — the conch

and cowrie we used as currency, displays of wealth to string

round the necks of our black-haired Pompeiian women.

We took them anyway, translucent as the sunlight our ships turned

to plough through: scant booty, but it was enough for Caligula.

What We Thought We Knew

Once we might have believed, like Pliny the Elder did, that honey comes out of the air and is

chiefly formed at the rising of the stars. There is no honey, said Aristotle, before the rising of

the Pleiades just before dawn. Once just before dawn we had that sense of honeyrising; stars

flowed wordless through our bloodstreams, we imagined we would take our place among the

Pleiades — two figures chalked against the sky, the great lovers, star crossed; but space

between us condensed then flew apart until we could no longer touch skin through heaven’s

architraves while species died in their thousands and what we thought we knew also faced

extinction. Once someone somewhere built an ark but forgot to tell the animals so the last

Bouvier’s red colobus, the lastPuerto Rican tree frog, the last gold Martinique Parrot (which

all ought to have been saved) instead became faint watermarks orbiting the dark with soot-

ringed eyes watching dancing bees become a thing of the past.

chiefly formed at the rising of the stars. There is no honey, said Aristotle, before the rising of

the Pleiades just before dawn. Once just before dawn we had that sense of honeyrising; stars

flowed wordless through our bloodstreams, we imagined we would take our place among the

Pleiades — two figures chalked against the sky, the great lovers, star crossed; but space

between us condensed then flew apart until we could no longer touch skin through heaven’s

architraves while species died in their thousands and what we thought we knew also faced

extinction. Once someone somewhere built an ark but forgot to tell the animals so the last

Bouvier’s red colobus, the lastPuerto Rican tree frog, the last gold Martinique Parrot (which

all ought to have been saved) instead became faint watermarks orbiting the dark with soot-

ringed eyes watching dancing bees become a thing of the past.

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated