Salman Rushdie. Photo courtesy: britannica.com

Don Quixote makes a reverberating Rushdian comeback. Quichotte is a testament of the modern man’s invincible courage and unwavering hope: a much needed reiteration of faith in a greener earth and a brighter future for our children

It is one thing to read a novel, another to want to get inside it.

Recently, I stirred awake in the middle of the night and even as I returned to “life”, as one does from sleep, the first semi-conscious thought that occurred to me was that I wanted to be with Sancho and Quichotte (they came to mind precisely in that order) in their crumbling Chevy and follow them on their Dante-ish road-trip across America in search of love, and eternal bliss thereafter. Something in me as a reader ached to stalk them on their journey to the end of the world through the quicksand-mix of the real and the imaginary, the factual and the fictional, the now and the never. That was halfway through the book.

Now, as I look back again, from the final pages of the novel, at the Indian-origin pharmaceutical salesman, Quichotte, in pursuit of a much younger talk-show celebrity Miss Salma R (also from India) making a final pitch for love in his old age, tugging along an imaginary teenage son, Sancho, it begins to dawn upon me that I as the reader have gained more from the journey through the end of the world than Quichotte, Salman Rushdie’s literary Don Quixote-double himself.

Quichotte is the story of a brother, sister, a beloved and a son. Quichotte is also the story of yet another brother, sister, and a son. (Sandman) Sancho is Quichotte’s figment of imagination as much as he is of Ismail, of Smile, of DuChamp of Brother, and of the Author. Quichotte himself is sometimes Ismail, sometimes Smile, sometimes Brother, sometimes DuChamp, and sometimes the Author. And by all means Sancho could also be Quichotte! This intricate meta-metafictional status of Quichotte unmistakably redefines the art of fiction writing. Quichotte is nothing short of a hall of mirrors reflecting the images of you, me and all of us. In many ways, this echoes for me the universal pain captured by the Urdu poet Qaisarul Jafri in one of his extremely popular ghazals made timeless by ghazal singer Pankaj Udhas’ rendition in the late 1980s:

Kis ko ‘Qaisar’ patthar marun kaun paraya hai

Sheesh-mahal mein ik ik chehra apna lagta hai

I see no strangers here ‘Qaisar’ who can I stone

In this hall of mirrors, every face I see seems like my own

Rushdie’s Quichotte is a site of urgent retrospection and necessary action. Private pain caused by loss, loneliness, sadness, disease, depression, depravity, secrecy and so on is here compounded by a larger-than-life sense of doom precipitated by the Apocalyptic times in which we live today. While the human world is on the verge of experiencing a social, cultural and political breakdown, the state of the natural world on planet earth, our only home, already defines the catastrophic. The only answer to this human conundrum, Rushdie demonstrates page after page, is to love and to be loved in every sense of the word; to end fights, mend ways, repair broken relationships, right the wrongs, shun superficial differences like colour, creed, and nationality and engage in an unconditional show of love for the human race at large and the irreplaceable worlds we inhabit.

Rushdie has everyone, everything, and everywhere of encyclopedic (whisper: and non-encyclopedic) significance covered. From Zeus to Queen Victoria to Van Gogh to Priyanka Chopra! From Mayflower to 9/11 to Brexit to ISIS! From Bombay to London to New York to California (including population details of scores of cities)! Warning!!! This is just the tip of the iceberg! This Biblical scale of Rushdie’s references some might consider a flamboyant show of his erudition. On the contrary, this cosmic scale of places, planets, people and events serves to bring all of humanity onto his mega-canvas and lend him the narrative extent to precipitate the fear of the impending Apocalypse/Doomsday hidden deep inside mankind’s collective conscience. And this sense-of-finality urgency allows the author to provide an impetus to his characters to hurriedly embark upon their reparatory journeys and actions: an interstellar-Endgame before Game Over!

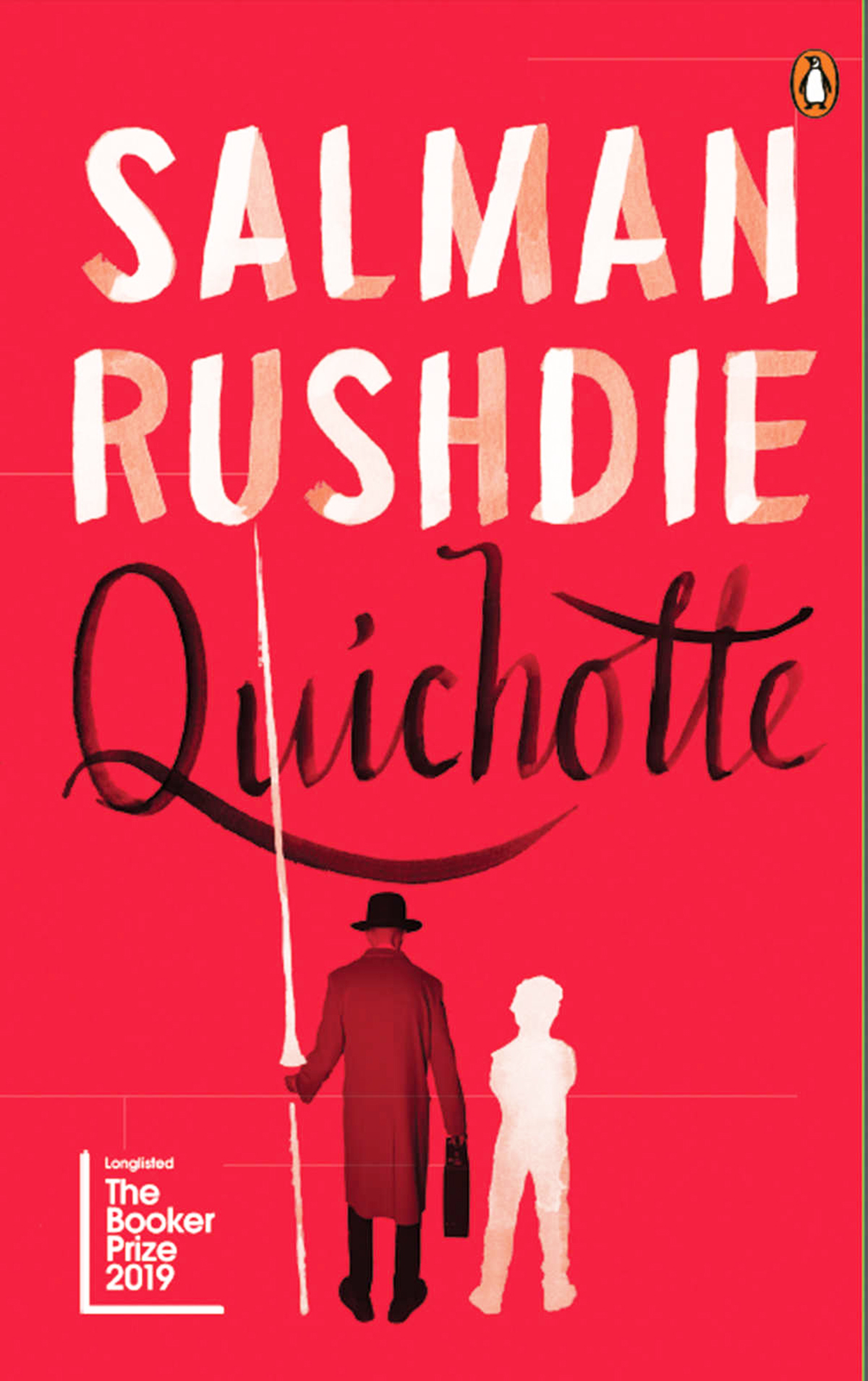

Quichotte is the most brilliant work of fiction by any author since Midnight’s Children (barring The English Patient by Michael Ondaatje). It is simply dazzling: cover to cover. The cover page of the Penguin India edition depicts a fiery red field being traversed by an elderly man and a young lad, our gateway into the book. The fact that the figures on the cover are facing not the reader, but away from the reader adds to the intrigue of the book. (Congratulations to the design team at gray318 for capturing the essence of the novel so acutely).

What lies inside is a paean to love and life: a literary panacea for the modern soul. Quichotte is a guiding star leading our end-of-the-world-generations to affirmation and healing. The book rings in our ears like a wake-up call: chapters begin with deafening bongs and end with skyfall disclosures. Nothing, absolutely nothing in this stunning postmodern play of imagination with its multiple narrative frames, multiple points of view, multiple Selves, and multiple voices, is predictable. For instance, when Beautiful opens the door and can’t see who rang the doorbell, the reader cannot but exclaim, “What the f**k”!

Rushdie is the greatest chronicler of our times. Quichotte is a testament of the modern man’s invincible courage and unwavering hope: a much needed reiteration of faith in a greener earth and a brighter future for our children. This book will season into a modern classic and will be celebrated by booklovers the world over for a long, long time to come. As for its immediate future, I see this impeccable modern day celebration of Cervantes, already shortlisted for The Booker Prize 2019, taking home the big award.

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated