Amitav Ghosh. Photo courtesy: amitavghosh.com

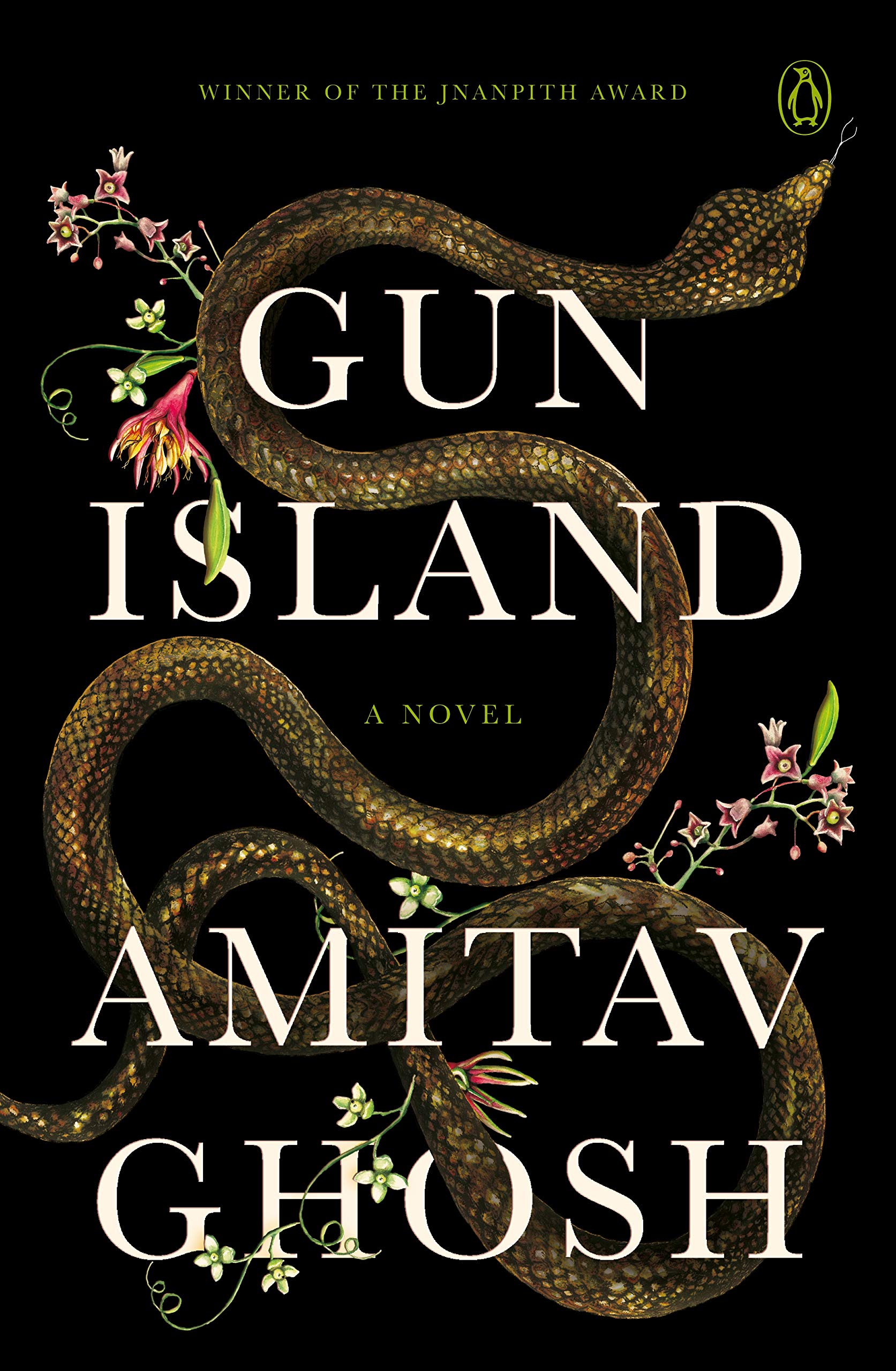

In Gun Island, Amitav Ghosh addresses the most pressing concerns of our times

Are you holding a copy of Gun Island? Welcome to The Hungry Tide, Season 2. Also, to the fictional sequel of The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable.

In The Great Derangement, Ghosh had taken literature, history and politics to task for their failure to grapple with climate change. While doing so, he had not spared himself, too, as a writer. In Gun Island, he seems to be making amends: he confronts climate change and the contemporary global refugee crisis head on with a story that has a Bengali folkloric legend at its core — that of a gun merchant (‘Bonduki Sadagar’), who ended up in Venice when pursued by ‘Ma Manasa’ (the goddess of snakes — celebrated in the cult 14th century Bengali poem, Manasamangal Kavya).

The gun merchant had built a small shrine to the goddess in a hamlet in the Sunderbans — which, a story went, protected it during the great 1970 Bhola cyclone (the deadliest tropical cyclone ever recorded), when all the surrounding areas had been devastated. The narrator of Ghosh’s novel, Dinanath Datta, ‘Deen’ — a specialist on the subject and a rare book dealer from Brooklyn, leading a lonely uneventful single life — gets an invitation (during an annual holiday in Kolkata) to visit this shrine to Ma Manasa before it disappeared in the mud. That visit, at first reluctantly undertaken, launches Deen on a voyage of discovery, in pursuit of the mythical gun merchant, that ultimately leads him to Venice.

Interestingly, in giving us this adventurous story, Ghosh harks back to a previous novel of his — The Hungry Tide (2004). In that novel, set in the Sunderbans, Ghosh had skillfully (and unforgettably) uncovered two suppressed histories — one, of the desperately poor and wretched refugees of Morichjhapi (thrice displaced after Partition) who were massacred by the West Bengal government in 1979; and he had interspersed that with the forgotten history of the Irrawaddy dolphins (Oracealla Brevirostris). The character through whom both the strands came together in the novel was the fisherman Fokir: his mother Kusum was one of the victims at Marchjhapi when he was only a child, and he himself becomes an invaluable local resource for Pia (Piyali), the Indian-American cetologist, as she conducts her research on the Irrawaddy dolphins. They come to share an unusual bond, and Fokir dies trying to protect Pia during a storm.

In Gun Island, the story shifts to the next generation — to Fokir’s son Tipu and Horen Naskar’s (another local) nephew Rafi — millennials, who were eking out an even more precarious existence than their parents in the delta, especially after Cyclone Aila hit the Sunderbans in 2009…. till the internet and specially smart phone technology changes them and their worldview forever.

One of the great changes that the smart phone, via social media, has wrought — Tipu excitedly tells Deen, while guiding him to the shrine of Ma Manasa — is to give desperate people in poor places images of a better life elsewhere on the planet, feeding desires and new-found aspirations to a point where the only option seems to get connected to an intermediary who can translate those desires into reality — for an (exorbitant) price:

‘The Internet is the migrants’ magic carpet; it’s their conveyor belt. It doesn’t matter whether they are travelling by plane or bus or boat; it’s the Internet that moves the wetware — it’s that simple, Pops... It’s not the 20th century any more. You don’t need a mainframe to get the Net — a phone is enough, and everyone’s got one now. And it doesn’t matter if you are illiterate: your virtual assistant will do the rest. You’d be amazed how good people get at it, and how quickly. That’s how the journey starts, not by buying a ticket or getting a passport. It starts with a phone and voice recognition technology…. And the same phone that shows them the images [of a better life] can also put them in touch with connection men.

…They are called dalals in Bangla. They’re the ones who make all the necessary connections for migrants, linking them from one phone to another. From there on, the phone becomes their life, their journey. All the payments they need to make, at every stage of the journey, are made by phone; it’s their phones that tell them which route is open and which isn’t; it’s their phones that help them find shelter; it’s their phones that keep them in touch with their friends and relatives wherever they are. And once they get where they are going it’s their phones that help them get their stories straight.’ (pp. 61-62)

Tipu, an impressionable listless teenager, gets easily tempted by and then involved in this ‘people-moving industry’ — one of the world’s biggest, with turnover in billions — successfully hiding it from both his mother Moyna (a nurse) and his foster-parent, Pia (who, out of both guilt and compassion, had done everything she could to give Moyna and Tipu a comfortable life in the Sunderbans, after Fokir’s untimely and tragic death trying to save her). Ironically, though, Tipu transforms from being a facilitator of refugee-movement to being a refugee himself in the course of the novel. His journey, with his partner Rafi, from the Sunderbans to Venice — via Bangladesh (where it actually begins), back into India, and from then on to Pakistan, Iran, and Turkey — is one of the most harrowing accounts of social media-fuelled migration in the novel. In his case, it gets extended even more, as he gets injured in the last leg of the journey and has to take yet another route — via Egypt — to finally join his partner in Italy.

When Deen arrives in Venice, he accidentally meets Rafi one day in the street. By then, Rafi had already been there for a while; and, as he tells Deen, is actually one among thousands of Bengalis, both from India and (especially) Bangladesh in the city. This is news to Deen, as he had thought that it was mostly people from Africa and the Mediterranean who were heading towards Europe.

The Merchant and the Scholar

In a recent interview to Mint Lounge, Ghosh said: “All my life I have been writing about merchants… At the heart of In An Antique Land is a merchant, the figure of the merchant also looms over the entire Ibis trilogy.” So it does. But it is no surprise — at least to the avid Ghosh reader — as to why it is so: if studied in detail, it will be seen that Ghosh’s oeuvre represents a continual attempt to explore the connections between different people and places in widely divergent spatial and temporal settings. And merchants are uniquely suited to serve that function — to link people and cultures.

But along with the merchant, there is also the persistence of the figure of the scholar in Ghosh’s work, as is the trope of the search (with one character trying to trace the work/ or life/or a crucial event in the life of another character, which holds the key to a mystery or a forgotten history). To give a few examples: the life of the ancient merchant In An Antique Land was brought to life by Ghosh himself, as a young scholar working on his doctoral dissertation; Shadow Lines is one long search by the unnamed narrator to unearth the mystery of his favorite uncle’s murder in a riot in Dhaka in 1964; in The Hungry Tide, the details of the Marichjhapi Massacre of 1979, that was hushed by the Left Front Government in West Bengal, is revived through the personal diary of a witness- a Left intellectual; The Calcutta Chromosome is framed around three searches, including the missing links in the history of malaria research.

In Gun Island, it is Cinta — Professoressa Giacinta Schiavon — an authority on the history of Venice (whom Deen had first met in the US, as a Catalog Assistant in the ‘Rare Books and Special Collections’ section of the library of the Midwestern university, and had bonded and been in contact with ever since), who guides Deen in his search for the origins of the legend of the gun merchant.

A key to this search is etymology. The ‘Bonduki Sadagar’ was driven out of Bengal and relentlessly pursued by the snake goddess as he travelled through alien lands — mysteriously named ‘Taal Misrir Desh’ (Sugar Candy Land), ‘Rumali Desh’ (Land of Kerchiefs), ‘Shikol Dweep’ (Island of Chains) and ‘Bonduk Dwip’ (Gun Island). Focusing on the history of the words in those names yields strange results and inches Deen closer to the heart of the matter. The ‘misri’ in ‘Taal Misrir Desh’, for example, turns out to be not sugar candy but Egypt — ‘misri’ being a mutation of ‘Misr’, the Arabic word for Egypt. Indeed, an important transit point for any merchant travelling from India to Italy in the 17th century. The other names, too, after going through Cinta’s etymological scanner, similarly help in mapping the route of the gun merchant’s travels — a route, as it turns out, still taken by migrants in the 21st century!

Cinta alerts Deen to the amazing parallels between the 17th century and the 21st century; and he himself ruminates on it while reading Henry James’ Aspern Papers (set in Venice):

It struck me that the Venice I had encountered today harked back to a time before that of The Aspern Papers — it was closer in spirit to the city that the Gun Merchant would have seen in the seventeenth century, another era when unaccustomed forces were churning the earth. Except that now it was unimaginably more so; it was as if the very rotation of the plane had accelerated, moving all living things at unstoppable velocities, so that the outward appearance of a place might stay the same while its core was whisked away to some other time and location.

(p. 166)

(p. 166)

Deen seems to be caught between two women — Cinta and Pia — with diametrically opposite world-views. While Cinta endlessly argues about the limitations of science and rational thinking and persuades Deen to open up his mind to coincidences and the uncanny, and to knowledge and thought systems that prioritise the intuitive over the analytical, Pia is unwilling to concede anything beyond what her research data yields. (In this novel, she is preoccupied with beachings and dead zones). And while Deen is romantically inclined towards Pia and there is the whiff of a romance between them at the end of the novel, we are left in no doubt that it is with Cinta that Deen has the deepest connection: she is to him a mentor, a friend and a mother-figure rolled into one.

“He gave me worlds to travel in and eyes to see them with”, the unnamed narrator of The Shadow Lines says of his uncle Tridib. To some extent, the same can be said of Cinta — she teaches Deen to look at his world anew.

Theirs is the only relationship that is realised in the novel. As the narrative moves at a break-neck pace, travelling from Kolkata to Sunderbans to Brooklyn to LA to Venice, working out the gun merchant puzzle as it goes along, and aligning different times, spaces and global concerns, there is little scope to delve into the internal arcs of personal relationships. We see the beginnings of that in the case of Tipu and Rafi in the Sunderbans, but then it gets swallowed up in the larger narrative of South Asian migration to Europe.

Gun Island is an intellectual tour de force — the best part of which is the unravelling of the mystery of the mythical gun merchant.

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated