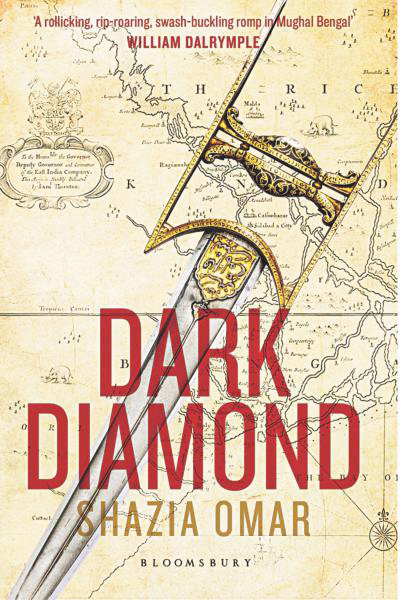

Shazia Omar’s Dark Diamond transports the reader into a magical world, beyond past, present or future, the world of the writer’s imagination.

Dark Diamond

By Shazia Omar

Bloomsbury India

Rs 399, pp 252

It’s a curious fact that in the Italian language, the word storia stands for both ‘story’ and ‘history’. Not surprisingly, the best historical novels aim to be just that, a seamless combination of both fact and fiction. But Shazia Omar’s Dark Diamond bedazzled me because it went beyond both impeccable historical research, and page-turning narrative skills. In the tradition of flawless fiction, it adds a third and important facet to the narrative surface: it transports the reader into a magical world, beyond past, present or future, the world of the writer’s imagination.

At a superficial level, the book is what the blurb declares it to be about. A little known but many-splendored chapter of sub-continental history: the Mughal province of Bengal of 1685 under the governorship of Shayista Khan. This historically verifiable narrative, however, is interwoven with the tale of a fictive diamond called Kalinoor, bedazzling yet be-cursed for its possessor.

The book is a riotous ride on a time machine, whizzing the reader not only through the imagined present of a distant past, but into a futuristic alternative reality. The historical verisimilitude and detailed description of a bygone era carries readers bodily into the past; the intimate perspective into the inner thoughts of the distinctly drawn characters, gives readers the immediacy of witnessing a present, unfolding before one’s eyes; and finally, the extravagant flamboyance of the writer’s imagination, creating surreal events involving dreams, legends, myth, and fantastic encounters of super-human characters with djinns and demons, pulls the reader into a volatile, futuristic world of altered reality.

It is delightfully apparent in every page that the writer thoroughly relished the writing of this novel. By the time I finished reading the book, I knew Shazia Omar’s opus about the ominous diamond would score highly on all the Four ‘C’s of flawless fiction. Cut, clarity, colour & carat, all are there, in different forms and in varying degrees.

The novel’s first ‘C’ is for being at the cutting edge of compelling storytelling. The chiselled facets of the narrative are demonstrated with each short and scintillating chapter, ensnaring the reader’s attention right from the fairy-tale beginning: “Legend has it…”. Thus opens Chapter 1, in the depths of the Golconda coal mines of Hyderabad in 1185, where we meet the bewitched gemstone of the title; Chapter 2 takes us to Paris, 1684, encountering the French adventuress Madeline; Chapter 3 brings us to Dacca, 1685, where we are introduced to Champa, the female protagonist, intriguingly holding “a cage of mice”; and in Chapter 4, we finally find ourselves in the presence of the superman Subedar Shayista Khan, hooded and incognito, beleaguered yet resoundingly unvanquished.

Already in these first four chapters, the second ‘C’’ is apparent from the clarity and meticulous conception of its plotting. We see the well-paced story progressing on a path, clearly visualised by the writer, but full of surprises to the reader, with each page and paragraph steadily advancing the story.

The unfolding of the tale involves the third ‘C’, the solid carat or weightage of a vibrant mix of characters of varied provenance, created as effective conduits for the story. The tale is told from various perspectives — Mughal, Bengali, Maratha, Portuguese, French, English — and voices, some belonging to female characters. Extraordinary women, fearless feminists, almost anachronistically modern yet inspiring, like Madeline and Ellora. But foremost among them is Champa, the dancer-protagonist, unflawed, and full of reason, the point-of-view character with whom readers, both women and men, can identify. The swashbuckling Shayista Khan, despite being the hero of the novel and imbued with superlative heroic qualities, is depicted as flawed and scarred, both physically and emotionally, making him vulnerable and thus, more romantic and appealing. We also meet a range of other characters, pivotal to the story, like the devilish Pir, and a more secondary but important character like the Portuguese pirate, Captain Costa.

The fourth ‘C’ is provided throughout in superabundance, as colour and colourful descriptions flood the narrative. Luscious, sensuous prose employed to deliver not just the beauty and regal opulence of a Bengal at the height of its glory, or the teeming realities of the natural or man-made environment, but a roiling excess of blood and gore, often gratuitous, made almost comical, thus digestible, by the use of extravagant language, tumultuous pacing and supernatural elements. It’s like violence in animated cartoons and comic books, the action almost visual as if taking place within the frames of a graphic novel, or a 4-D film.

Shazia Omar’s mastery in the deployment of language is apparent in the skill with which she adapts English to make it appropriate to the context. Almost incantatory as a fairytale, her prose is rhythmic and alliterative like poetry. You feel you are in another era, an epic time.

For example, here she is describing Chowk Bazar. The assonance, consonance, and alliteration within the measured words and phrases, are pleasant to the ear, and lull one into believing that one is in some legendary, mythological world distinct from modern day.

“Under the crimson canopy lounged sinister mercenaries waiting to catch whiff of golden opportunity. Here merchants could sell stallions from Arabia, camels from Egypt, gems from the coast of Masulipatam, dark secrets, pink lies, promises and primroses by the dozen….”

Or listen to the mesmerising catalogues of objects: “…manuscripts from Mongolia, volumes from Venice, portraiture from Portugal, epistles from England, and astronomy charts from Arabia….” Or the ‘h’ and ‘r’ sounds in this phrase: “Here one could hire cutthroats to execute with words or swords any brutality for a reasonable price.”

Her dialogue is convincing and appropriate to the situation and speaker, pithy and contemporary, or courtly and flowery, as required. I particularly enjoyed how the writer casually introduces exotic terms and names into the text, adding historical authenticity and ethnic richness without this causing any obstacles to understanding the meaning.

For example, the pages are strewn with the names of a variety of weapons: “sheathed khanjars”, “the hilt of his shamsher”, “double bladed bichua”, “gold katara,” and “Damascan seif”, explicated in context as being either a dagger or a sword. The same with other vernacular words like “a glass of sharab” or being cooled with “peacock feather pankhas”. All this functions to centre the world in its own linguistic and cultural context.

The adventurous tale progresses through many entertaining twists and turns, taking readers on a breathtaking journey, requiring the willing suspension of disbelief. Readers may find the ending to be a bit abrupt and unconvincing, and that the journey was more memorable than the destination. But no one will dispute that the trip was worth it.

But what makes this novel a truly rewarding experience, apart from its entertainment value and the wealth of historical information it imparts, arises from the author’s dedication of the book to present-day Bengali youth. I salute Shazia Omar’s attempt to narrate a story of a heroic past in her commitment to bring hope to a dismal moment not only in a Bangladesh battling religious radicalism, but a world rife with political extremism.

Maybe it is time to imagine larger-than-life humans, imbuing them with our hopes and beliefs, and to dream of alternate realities. The author uses a well-known couplet of Omar Khayyam as epigraph, but the novel’s message seems to be the opposite: if we cannot lure the moving finger to cancel even half a line of pre-destination, perhaps it’s time to take control of our own fate, and like Shazia’s depiction of Shayista Khan, it’s time to rewrite our destiny with idealistic dreams, create a whole new storia. And in the process, we might unearth, if not another Hope Diamond, perhaps, the more glowing gem of hope.

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated