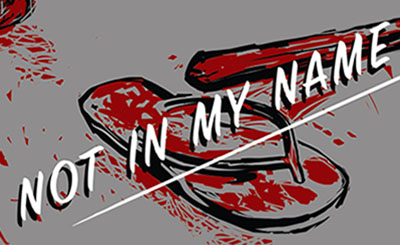

Editor’s note: An evocative portrayal of a woman’s journey through a polyamorous marriage, this story unearths the raw complexities of tradition and intimacy.

**

I wonder if you know that the term polyamory was coined during the 1990s in America to define a form of consensual emotionally and/or sexually intimate relationship among multiple people. Half a century before that, and halfway across the globe, in a small town of North India, Urmila unwittingly traipsed into a polyamorous relationship when she circumnavigated — tethered to her bridegroom — a mandapam, the sanctum sanctorum of Hindu wedding rituals, ostensibly endowed with divine power to guarantee an auspicious, fruitful and happy married life.

Literally carried away from her father’s portico (her mother had left them for her heavenly abode during childbirth) in a palanquin festooned with flowers, largely marigold, she sniveled noisily into her handkerchief as she bade farewell to him and other relatives gathered for her wedding. The smell of marigold petals overwhelmed her olfactory receptors even as expectant anticipation of a blissful companionship in her newly acquired marital status somewhat assuaged the ache of leaving the house where she had spent the sixteen years since her birth.

This tenuous optimism prevailed up to the moment that Prem, her life partner, approached their flower bedecked nuptial bed. The match had been fixed up, as was customary then, by the parents, and she had not yet seen Prem’s face, only a photograph. She sat on the edge of the bed, nervously nibbling at her pallu, the ornate, embroidered end piece of her saree that she had draped her head in. She flinched as he approached but could not resist looking up at his face out of suppressed curiosity; her first impression was that he was good-looking. But he appeared restive.

His first words, spoken gruffly, devastated her, “Take off your clothes. Hurry.”

She sat stunned and shocked, as he ordered her repeatedly to hurry up and undress, while removing his churidar pyjamas — the tight-fitting trousers worn for ceremonies. He did not bother to remove his sherwani, the ornate, closed neck top he had worn for the wedding. Her protestations were of no avail as he then proceeded to mercilessly lift up her bridal saree, disrobing her just adequately to forcefully enter her and shattering — in one fell swoop — her barely pubescent hymen, her conjugal dreams, and her chaste innocence.

When he collapsed on her a few moments later, and left the room, she felt lifeless. She lay on the bed, sobbing uncontrollably until she had no more tears left to shed. Her wide open eyes stared at the floral canopy the bed had been adorned with, as if in search of some solace, until the moist burning and painful throbbing in her nether regions compelled her to get up and visit the toilet.

She spent a long time lathering her body with a soap cake smelling of disinfectant and reminding her vaguely of a hospital. And then washing it off with copious amounts of water, the sound of cascading water drowning her loud sobs. Repeated soap application and washing of her private parts did nothing to take away the feeling of being unclean and impure.

Still feeling soiled, but exhausted by her exertions, she finally returned to her bed to change into the night clothes she had kept ready. As she was changing, Prem entered the room. He did not seem to be tense or in a hurry now. But his intent was clear. For Urmila, the second time was even more painful physiologically, and more humiliating emotionally, than the first. As Prem’s grunts intensified in tempo, Urmila moaned inconsolably in pain.

She wept and slept fitfully all night, waiting to get away to her home for the ritual trip next morning, determined to tell her father of Prem’s brutality and to never come back to his home. In keeping with tradition, Prem accompanied her for the visit to her home. He seemed to be a completely transformed person during the journey and she found it hard to relate him to the brute who had violated her so savagely the night before. He made no attempt to make conversation but remained attentive to her need to keep to herself. Travelling in silence, she had time to think about the possible effect her revelation would have on her father. By the time they reached her father’s home, she no longer had the will to belabor her father with what destiny had bestowed upon her. At some time during the journey, she was determined to face the situation on her own.

Time helped to heal Urmila’s scars of the first night as she worked hard to push them from her memory and slid smoothly into her household responsibilities. She sensed that her efficiency in discharging them was increasingly earning Prem’s approval and possibly fondness. Gradually she found a change in his sexual approach and she began to look forward to their consummation, which provided both of them with mutual satisfaction albeit floundering in its procreative purpose. Even after two years of marriage, Urmila continued to long for her womb to germinate. Prem’s relatives were openly accusatory, questioning her fertility. His mother wanted her to be examined by a dai, a professional adept in assisting child birth and child care and considered the equivalent of a gynecologist in those days. Prem agreed but Urmila vehemently opposed the idea. She asked him to wait for some more time and see. Sensing his reluctance, she hinted that it would not be good news for the family if the dai declared her fit to conceive. Reluctantly, Prem relented.

Ever since Urmila’s arrival, Asha had been around as a household help, her presence a diurnal one; she left before sunset to unite with her parents who stayed in a thatched hut on the grounds adjacent to the house itself. Around this time, Prem started paying her a wee bit more attention than hitherto (just as this story and you are doing now). He would stop and ask her if all was well with her, occasionally check if she needed more money or clothes, and look for an opportunity to talk to her casually.

One morning, Asha did not turn up for work. Urmila walked up to their hut to call out to her. As she approached the hut, she heard loud voices. Asha’s mother came out, still talking and cursing, in a garbled sequence, her own fate, Asha, and some unknown perpetrator responsible for the demon growing in Asha’s womb, the manifestation of which had been Asha’s morning sickness that day. She was determined to evict Asha from their hut while Asha wept for forgiveness. Her father wailed in despair one moment with his hands raised heavenwards, while hurling filthy invective at Asha the next.

She suddenly realized that, unbeknownst to her, Prem had also arrived at this cacophonous scene. Just then, Asha’s mother went into the hut and came out yanking by her hair a howling Asha, struggling to free her hair from her mother’s grip. Her mother heaved Asha away from the hut and she fell sprawling on the ground. Prem was instantly by her side and helped her up. As Asha rose to her feet, she clung on to Prem as if for support. In that instant, Urmila knew.

Asha was given a spare room to live in the house, her parents inwardly blissful that their disgrace had not become a public show while outwardly continuing to beat their breasts, largely metaphorically, but occasionally impacting their torsos with their calloused hands. That night Prem approached Urmila as bedtime came and sat down on the edge of the bed.

“Urmi….” he started.

“I hate you.” She spat out.

His voice was even, “But I don’t hate you. Even though you are unable to give me a son.”

“It is not my fault that I………” she stopped short, her hand involuntarily moving up to cover her mouth. Prem shot a glance towards Asha’s room, sub texting his silence. Urmila’s defiant gaze mellowed and fell. She was silent.

Her silence on the subject of Prem and Asha lasted through decades of the three living under one roof in a polyamorous relationship. She wanted to rebel, to move away from Prem, Asha, and the house as she felt suffocated knowing both of them were around, but she knew that that would be a dark alley to enter. Prem would never plead with her to stay back if she wanted to leave and she could not go back to her father’s place. And there was no other place to go. After the first few days, inertia took over and she realized that life had to go on.

Within the confines of the four walls of the house, Prem tended to both the women he felt emotion for — one whom he had wed, and one who had borne his child. He would spend some nights with Asha, always returning to the bedroom he shared with Urmila before morning came. Urmila’s only protestation when he returned after a night with Asha was that she turned her back towards him when he slipped into the bed. Prem did not force himself on Urmila ever again but performed all other duties of a husband, looking after her and caring for her. For her part, Urmila derived great solace from not having to grant conjugal favors to Prem.

The birth of a son to Asha came as a non-event; indeed, Asha discharged all her household duties in their entirety until the day that Dai Ma had to be called to help her in a natural childbirth. Ten days later, she was back at her duties, looking after her nursling as well as all her erstwhile chores. The son was named Loki.

Urmila often wondered in her private moments why Prem did not leave her. Was it out of fidelity to the mantras recited at the mandapam vowing to protect and tend to his wife? Or a sense of remorse at breaking the vow about being faithful to her all his life? Or was there a romantic or emotional attraction he felt towards her? Depending on what her state of mind was, she would favour one of these options. She would be ever thankful to God for her still being under the shelter of Prem’s home. Right until she died, rather prematurely, possibly consumed by her grief.

Although sequestered from Prem and Asha, she had not been alone. Closeted with her thoughts, she would spend time in her own room, penning down her innermost contemplations in a diary which became her companion, confidante to her innermost secrets. Had she not done that, and had the diary not been discovered after she passed away, this story would not have drawn breath.

You see, I am Loki. And I found the diary.

Comments

*Comments will be moderated