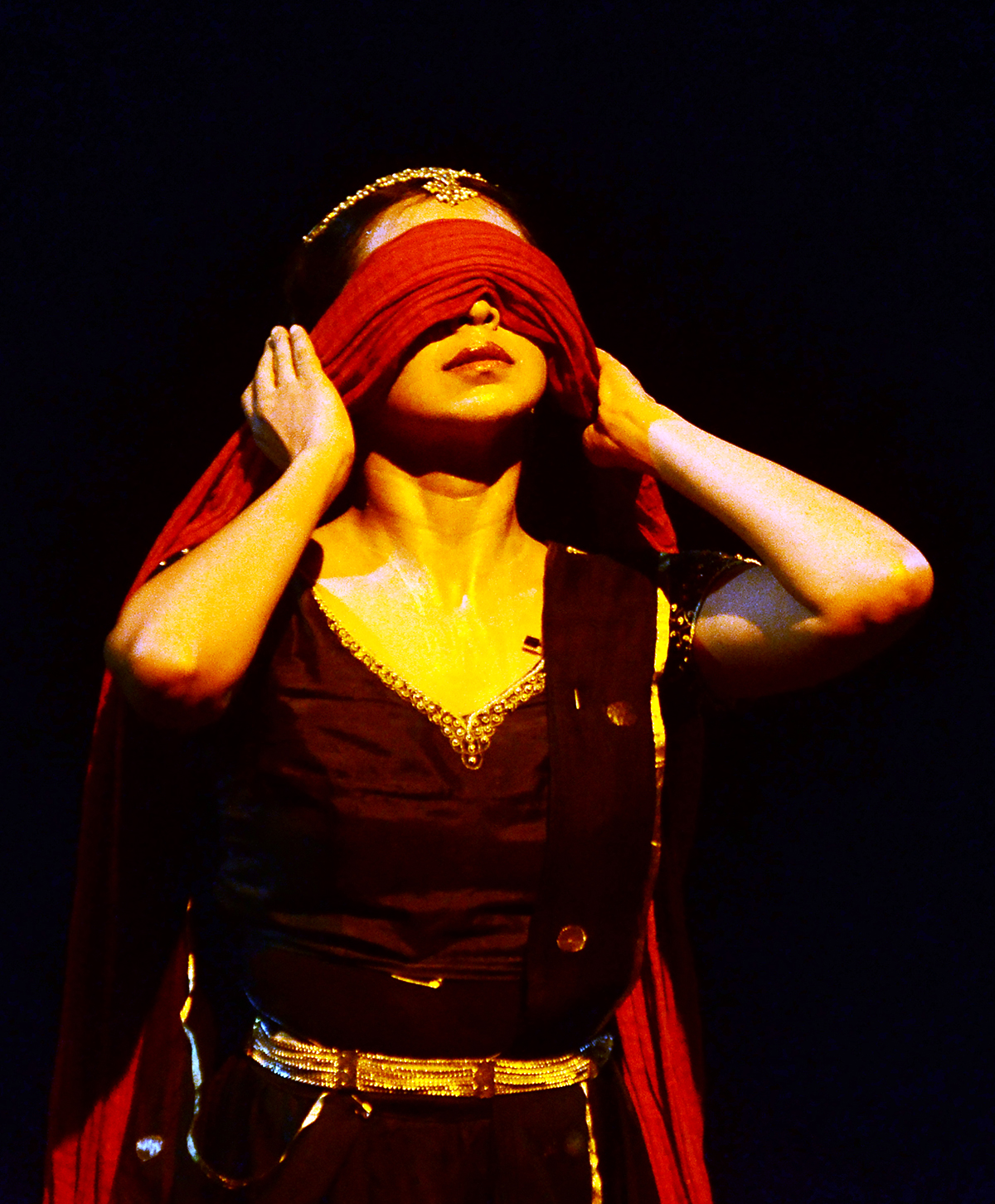

Sanjukta Wagh during the performance of Akath Katha. Photo: Gautam Kirtane

Sanjukta Wagh on the inter-disciplinary landscape of genres she juggles — theatre, dance, music, choreography, and writing

Sanjukta Wagh, who straddles several disciplines, has developed a language of dance theatre that uses the idiom of Kathak as the base and draws from her experience of contemporary dance, theatre and Hindustani music, leading to interdisciplinary and collaborative performances. Her choreographies — Rage and Beyond: Irawati’s Gandhari, Bheetar Baahar, Ubha Vitewari, Putana And I, among others — along with traditional Kathak solo and ensemble performances, have won her applause across the country and abroad. Recently, she became the recipient of the Vinod Doshi award for significant work in performing arts.

Wagh has researched and created the text for several of her own productions. She has also composed music for her work. Her research on improvisation as a studio-based practice and as performance, along with her exploration of dance as music and live music, has led to several one-on-one collaborations and experiments. Wagh also served as the curator for dance at the Kala Ghoda festival in 2009, 2012, and 2013. She is the founder of an interdisciplinary initiative called beej in Mumbai, which has been engaged in exploring the creative process and improvisation, alternative methods of classical dance pedagogy and collaborative performance since 2005.

As a Kathak dancer, Wagh was drawn to the world of storytelling via movement, words, melody, and rhythm at a very young age. Restless within the idiom of Kathak as a soloist, she wanted to use her training and language to express all the dilemmas and discoveries that her artistic quest led her to. Hence, though she is firmly rooted in the classical, she says she is unafraid of taking risks, improvising and exploring the boundless in these spaces of intersection and interdisciplinary convergings. “I think my work belongs to the grey areas in between theatre and dance that defy classification,” she says.

Excerpts from an interview:

Ina Puri: Warmest congratulations, Sanjukta, on a spectacular performance of Rage & Beyond: Irawati’s Gandhari in Delhi recently. Watching your one-act presentation that so skilfully wove music, dance and theatre together in a single cohesive narrative reminded me of another friend and dancer Ranjabati Sircar. I had collaborated with her in 1995-96 and produced Cassandra, a solo act quite provocative and daring, considering those early times. “A woman deep in wisdom as in suffering” the character of the tragic Trojan Princess Cassandra came back when I watched you enact the role of Gandhari, a woman whose courage and noble spirit remained unvanquished till she embraced death. Tell us of the genesis of this production.

Sanjukta Wagh: Thank you for your response. I would love to see Ranjabati Sircar’s Cassandra if you have any footage.

When professor of Sociology and friend, Gita Chadha proposed that I devise a performance on Irawati Karve’s Yuganta (The End of an Epoch, 1969) for the final cultural presentation for a seminar on “Feminisms: towards a State of Alteredness” organised the department of Sociology, Mumbai, I was reluctant. Karve’s Yuganta, which has been hailed as one of the first contemporary re-interpretations of the Mahabaharta by a woman anthropologist of the 1960s was too prosaic and I didn’t feel any inspiration to begin for several months. I read and re-read the book and several versions of the Mahabharata, several essays on and interpretations of the Mahabharata, watched Peter Brook’s Mahabharata, read Dharamvir Bharati’s Andha Yug (1962), other information on and essays by Karve. When time came to choose a character, the one that called out almost from inside my being was that of Gandhari. There was a curiosity. I wanted to question her motives. I had no intention of either glorifying her or essentialising her which often happens especially in Classical dance interpretations of mythological characters. I wanted to bring her out in all her complexity. My trigger question was: What could motivate a woman or human being to wear a blind fold? What does it mean to lose a sense organ? And moreover to choose to lose one’s sight? I had no idea then that inhabiting this character and my long journey with her would alter me significantly as well as change my course of life and beej’s first all India award-winning work.

Ina Puri: While in the case of Cassandra, the text was by Christa Wolf, in the case of Gandhari, the text you draw inspiration from is Yuganta. When did you discover the story and what convinced you to select the story of a medieval queen who history would remember as the unfortunate mother of the Kauravas, who perished in the epic war in Mahabharata?

Sanjukta Wagh: My co-conceptuliser Gita Chadha and I came up with an interpretation that Gandhari’s choice was motivated by a rage directed inward as it could not find an outlet. This is intentionally opposed to the popular notion of Gandhari as pativrata who gave up her sight as her husband was blind. Here was story of the Mahabharata being retold by the iconic queen with blindfold, exploring her relationship with her husband, her sons, her nephews, and other characters in the Mahabharata. As Gandhari further pervaded my conscious and unconscious states, as mythological characters inevitably do, I began to rediscover nuances and shades in her character and I wanted to explore her much more. A poem arose. The refrain was…

“My eyes were closed.

My choice had been made

I was Gandhari, the empress with the blindfold.”

I wanted to explore Gandhari’s relationship with the blindfold. Some questions that arose were: Does she see it as her identity? Or does the blindfold wipe out her identity? Therefore, should I call it “the” blind fold or just “a blindfold” or “her” blindfold? I wanted to portray Gandhari’s silent outrage to Draupadi’s disrobing by her sons, and the paradoxical episode of the first time she sees Duryodhana, not a kshatriya warrior she ascribes him to be but just “a trembling little boy afraid to confront his mother’s naked gaze. I also problematise the reading of history with convenient blindfolds, which we see in today’s day more than ever. Karve also talks about kin and social equations in her text. I began to see the dilemmas of a Kshatriya woman through Gandhari’s eyes and there arose another poem. “Kshatriya Woman Births Weapons” was born. It also speaks about the futile and mindless violence of wars.

During the performance of Rage & Beyond: Irawati's Gandhari. Photos: Narendra Dangia

During the performance of Rage & Beyond: Irawati's Gandhari. Photos: Narendra Dangia Ina Puri: It was not an easy role to essay especially because you portray Gandhari across time, transforming from a carefree princess to an elderly woman burdened and punished by destiny for no fault of her own. How did you plan and prepare for the role?

Sanjukta Wagh: In my process of embodiment, I began with my own sensorial self as the creator of the piece. My process involved grappling with my own senses, touch, hearing sight, sitting with a blindfold, and reliving the Mahabharata as Gandhari. Slowly, a script began to emerge. It almost came from my body as much as from my mind. Musical possibilities began to arise in rhythms and silences. I also began collaborating with music composer and guitarist Hitesh Dhutia, who began entering the space with his live acoustic guitar. His embodiment of the narrative was like a sound track that led the story ahead. There began an exchange with sound and silences becoming triggers for the choreography, much of it improvised to progress through Gandhari’s non-chronological journey. My choreography often uses only ghungroos and tatkar (footwork) along with spoken bols as percussion along with sung melodies. There are abhinaya sequences in which the story proceeds non-verbally. There are silences deliberately inserted to create an atmosphere.

The third player in the process was light designer Deepa Dharmadhikari, who also became an outside eye watching many rehearsals critically and giving her input. Deepa’s powerful lighting combined with the sound design consisting of sound, text, melody and silence in equal measure drives every embodiment of Gandhari.

During the performance of Bheetar Baahar. Photo: Madhusudan Menon

Ina Puri: What was deeply impressive was the fact that you could sing as beautifully and effortlessly as you did despite dancing, dancing for long spans of time! You use Kathak movements throughout and the challenge is that you are performing and singing alone, without the support of anyone else. Tell us about your personal journey as a trained Kathak dancer, singer, choreographer and theatreperson.

Sanjukta Wagh: I’ve had sustained training with Rajashree Shirke in Kathak for over two decades, Pandit Murli Manohar Shukla in Hindustani music, and been mentored in theatre by Chetan Datar and G. Venu with whom I studied Navarasa sadhana. I also have a masters in literature from SNDT women’s university. I won the Charles Wallace scholarship to study contemporary dance in London at the Trinity Laban School. There, I delved in various subjects, including choreology and choreography and the power of the classical dance languages came home to me in a place far away from home. I began seeing Kathak as my boundless language of expression which did not have to succumb to rules of the traditional repertoire which had begun to make me restless and want to explore other dimensions. I also wanted to question saundarya hetu (for beauty) in dance and create a work that did not glorify or essentialise characters as most dance ballets or presentations I had come across did. I was deeply impressed by the work of Kalairani, had researched Chandralekha and wanted to create a form of expression where the concept was centrestage not the dancer.

Ina Puri: What about your earlier productions? Have you used dance and music together before? Tell us about Jheeni.

Sanjukta Wagh: I began exploring improvisation as performance on my return from London in 2010 and did my first collaboration Bheetar Baahar. I wanted to experiment with the idea of dancing a completely improvised piece. I wanted to address improvisation as a skill that grows through practice and engagement. A musician learns how to play and once he is familiar with the structure and technique of music, he can let go and make the music happen, respond to immediate sound around him, jam. In the case of Indian classical music, one allows the raga to unfold. I began asking similar questions in dance: Can I allow the space around me to dictate what unfolds? Can I respond to the floor, the air, the vibrations…so that I am not the dancer at all times but also the danced?

This process helped me discover myself, my dancing body and creating meaning with the dynamic play of body, sound and space. And I continue to explore improvisation as a studio-based practice and it is part of my teaching methodologies as well. Jheeni with my three fellow musicians — Hitesh Dhutia, Vinayak Netke and Shruthi Vishwanath — is a sonic weave of bhakti poems that has a large improvisatory element in every performance. My work is also a reaction to the increasing popular idea of dance today as a finished product, to be marketed and sold as opposed to a process which has within itself tremendous transformational energy. In the fast-paced world we live in, young dancers seem to be getting increasingly divorced from the subtle in their art forms and becoming slaves to virtuosity and speed. If we as artists do not start cultivating subtlety in our own and each other’s forms, we leave the audiences no choice except to be faced with performativity and spectacle for its own sake.

Ina Puri: The larger scale of socio-political reality is hard to ignore. Would you like to elaborate?

Sanjukta Wagh: I have always been encouraged by my mentors like Mitra Parikh (literature professor) and Alaknanda Samarth (theatre actor and maker) to place my work in the larger context of the world around me. In the present-day world where forests, tribes and animals are endangered, the text about the burning of the Khandavaprastha forest and its reclamation as Indraprastha that Gandhari speaks about it the play along with the victors always being ascribed the glory became very pertinent and uncomfortably real: “We all have our blindfolds, you and I. One’s that we choose to wear as we please. Closing our eyes on that which we do not wish to see. Closing our eyes on the war that looms on the horizon.”

Ina Puri: Tell us about beej and its programmes.

Sanjukta Wagh: Beej means seed. My colleagues Neha Kudchadkar and Pranali Kakade, and I founded this. We have been exploring three strands of dance process, pedagogy and performance. Rooted in the language and grammar of the classical, beej has been engaged with archiving dance process, starting conversations around interdisciplinary questions on art and culture in the beej garage, imparting classical dance training in newer and more embodied innovative methodologies of education for both children, adult learners and professionals in the beej school of Kathak and create avante garde work in dance, music and theatre in beej productions.

Ina Puri: There is a renewed interest in classical singers and dancers, in recent times, we have Gauhar Jaan and other productions to name a few, bringing alive another era. Do you think a more contemporary interpretation of classical forms like Kathak is likely to encourage younger people to the performance?

Sanjukta Wagh: In my experience, if the work is honest and speaks to the self with a sense of immediacy, its language does not matter. Somewhere, it reaches. I don’t think dancers or actors should limit themselves by tradition but immerse themselves in many traditions so as to forge their own languages. It is also very important to risk failure. Not all my experiments have had “success”. But they have definitely led me to newer methodologies of working.

During the performance of Ubha Vitewari. Photo: Madhusuadan Menon

Ina Puri: The idea of a minimalistic stage setting is very appealing. I loved the idea of the red scarf being used as a prop in so many diverse ways. Do you think Gandhari will work best in a more intimate space like Oddbird (Theatre & Foundation, a collaborative centre for the arts in Delhi, where Wagh performed)?

Sanjukta Wagh: The only prop I decided to use was a cloth which I begin by tying around my eyes and singing of the “sat rangisapna” (multi-hued dream) that Gandhari had. In fact, the play begins with the action of seeing, followed by tying the blindfold and its untying.

This red cloth becomes a borderline between stage and audience and takes on a life of its own as the play progresses, becoming alive and potent. I began exploring Gandhari’s own relationship with her blindfold: it becomes sometimes her protector or rather the protector of her ego, or burden she can’t throw away, a noose around her neck, a dividing line in her many shades of personality. Having a physical object to work with reinforced the sensorial approach that I had begun with. The smell, the colour, the texture of that cloth carries so many sensations felt during rehearsals, readings and discussions that all those seep into the performance.

I think the play does work well in intimate spaces, but we have also had very good responses in large proscenium stages like the Vinod Doshi theatre festival, Pune, the World Music Institute festival “Dancing the Gods” in New York and the Royal Festival Hall at the Southbank Centre’s Alchemy festival London.

Ina Puri: You talked about how you also encounter your own rage, and the blindfolds that we perhaps unconsciously inflict upon our individual and social selves. Would you elaborate?

Sanjukta Wagh: As I mentioned before, I began asking Gandhari her reasons to lose or cover up her sense organ. But in the process of inhabiting her space, I encountered my own blindfolds — some psychological, some a result of hardwired social conditioning that did not allow me to “see” the world as it was but as I wanted it to be, or as I was told it should be. Opening up to Gandhari and playing her opened my eyes to my own rage that was bottled up, my strong outrage about many injustices that remained unvoiced. The blindfold today is a metaphor and one must start by understanding that “every telling of history is filtered” by the blindfold that the historian/storyteller adorns. So, at least we may be conscious of our own positions, instead of turning a blind eye or unconsciously adopting ideologies or stances which I firmly believe we should take in all consciousness as thinking, living beings with agency in our world.

Ina Puri: Hitesh Dhutia has risen marvellously to the task set out for him. How did the collaboration pan out?

Sanjukta Wagh: Hitesh is also my partner off stage so there is definite connect that we have. This was his first collaboration with dance or theatre since we began in 2014. We have literally grown with every show of the work and along with the textual script, the musical score has also altered, evolved and transformed tremendously. Hitesh has an incredible and understated presence on stage and he makes his own emotional journey as Gandhari and her various inner conflicts through the piece. We have both deliberately used silences to enhance many moods in the play which also makes it very unpredictable. The absence of any other outside percussion adds to the rawness, intimacy and immediacy of the piece. Hitesh’s sensitive composition and heartfelt rendition of the live score won him the best sound design award for Rage at META (Mahindra Excellence in Theatre Award) in 2015.

More from Arts

Comments

*Comments will be moderated

Waiting for more shows from Sanjukta.. some abhang performances on the occasion of Ashadhi Ekadashi?

suchitra gupte

Jun 26, 2020 at 16:55