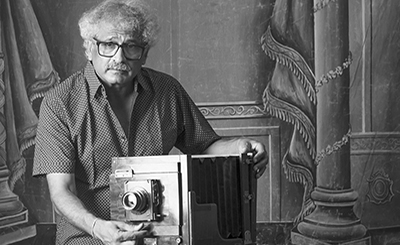

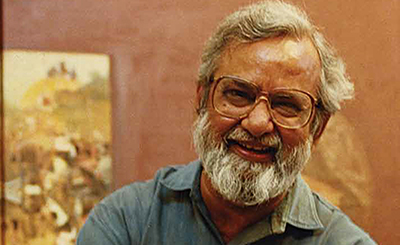

A design by Vriksh. Photos courtesy of Vriksh

The Covid-19 pandemic and lockdown has severely affected the handloom sector, which was already reeling under the impact of demonetisation and GST. For centuries, the handloom weaver has continued to work from home, offering the world the choice of a conscious living, which is sustainable, local and green. These weavers offer me the hope and the conviction to carry on my journey in the handmade sector

Recently, I finally finished revamping our website vrikshdesigns.com, designing a new look with an e-commerce integration. While summarising a decade of my work into the new website and sifting through hundreds of photographs and videos with long hours of Google hangout calls and Zoom meets with my studio team — the process kept taking me back into the memory lanes of weaving-villages where I work, some of them from my early years in Odisha. Once every two months, I visit Odisha to meet with my team of handloom weavers. Over many rounds of tea, our conversations traverse across topics around work, inspirations for new design collections, family, politics, travel and life. Odisha is a goldmine of textiles and it may take a lifetime to discover all the hidden treasures in handlooms. Even today, almost each and every district in Odisha offers exquisite and unique textiles from fine tussar silks of the coastal belt, curvilinear ikats from the west, tribal weaves and natural dyes of the south. One can never get enoughof it! In design studio Vriksh, I work with handloom weavers who are masters of their art, offering new innovations to the traditional designs while retaining the cultural significance associated with this living tradition.

I recently returned home after attending a short course on South East Asian Textiles atthe Victoria and Albert museum in London. It was an extension of my ongoing research on Vriksh’s new collection “Bali Jatra”, launched early this year. The collection is a reliving of the popular festival Bali Jatra or Boita Bandhana celebrated every year in Odisha, commemorating the historic textile trade between India and the South-East Asia. An unseen combination of Odisha’s curvilinear ikats with subtle hints of Andhra’s chintz motifs, Indonesia’s spiralling temple layout, Laos’s extra weft patterns and Thailand’s colour palette. The collection offers a contemporary twist born out of this beautiful cultural exchange reflecting distinct characteristics from every region. It is an explosive amalgamation of various design vocabularies combined with innovative ideas, using the famous Ikat and Jala techniques of Odisha in handwoven silk saris.

The handloom sector, while being the second largest employment source after agriculture in India, also provides us with a unique social and cultural identity.

On my return, I was looking forward to visiting Odisha and meeting weavers to share stories of my UK visit. The sudden call for a nation-wide lockdown meant that I had to wait till the situation was under control. When the pandemic hit India and a nation-wide lockdown was enforced, like many, I, too, was clueless about how the situation would panout. During these uncertain times, my art has been my best tool of communication during physical distancing. The meaning of design organically took new directions, it expanded beyond textile art. I wanted to extend support to the weavers beyond helping them meet their financial needs so I would call them regularly to know if they are keeping well and safe.

During a conversation with Ajaya, a highly skilled weaver, friend and a close associate of Vriksh, he said, “Last year, my friend left for Surat in search of better earnings, but even now he continues to look for them. He tells me life is not easy there. Now he is stuck there with no food and money. I wish he comes back home safe and rejoins the loom.”

Incidentally, Ajaya had also returned from Surat a few years back for similar reasons.He adds, “The migrant labourers in cities have faced the biggest challenge during the lockdown. In this new normal, wouldn’t choosing local hand-made processes like hand-weaving in villages help limit migration to urban cities?”

'We are lucky that this local practice of making clothes is a continuous living tradition which hasn’t died.'

The handloom sector, while being the second largest employment source after agriculture in India, also provides us with a unique social and cultural identity. The entire process of weaving a handwoven cloth is a coming together of people, each with their own skill sets and women form an important part of this entire process. But it needs urgent attention of the government as well as the conscious consumer to strengthen it.

The last few years were already challenging, dealing with blows of demonetisation, then GST and now the COVID-19 pandemic has further crippled this industry. Orders have been cancelled, there is a blocked inventory of stock that artisans and designers are unable to sell due to market collapse. This has led to exhaustion of running capital; shutting down of small enterprises and piling debt. Handloom weavers have the advantage of working from home but currently there is no raw material available to continue work. “After the lockdown, not just India but the world will change, and we all need to come together with creative ideas to make it safer,” says Mano bhai, an ikat weaver associated with Vriksh for more than ten years.

Lakshmi is a tussar silk weaver from Jajpur district who has a keen eye for detailing and loves to experiment. She says with a sense of pride,“I am not a machine. It takes me minimum a week to weave a sari and sometimes a month, and no two are ever the same. I prefer weaving quality over quantity giving each piece a unique identity.” India is the largest producer of handlooms and handicrafts in the world. Our handloom weavers and artisans have been preserving the knowledge, skills and wisdom of self-sufficiency.

Vriksh’s new collection “Bali Jatra” (top) was launched early this year. An artisan at work.

We are lucky that this local practice of making clothes is a continuous living tradition which hasn’t died. Today, when the world is leaning towards slow and sustainable fashion, India can be a leader in guiding the world. I realised that this is the perfect time to share these dialogues with people beyond the crafts community. In April, Vriksh rolled out a social media campaign titled #WeavingOurWayForward, aiming to reach out to urban audiences. The response was quick and people were eager to join hands.

Some of us craft designers and organisations came together as one voice and launched an awareness campaign #HandmadeInIndia, a first-time experiment to kickstart a social movement to generate awareness on how essential is handmade in our lives and why we urgently need to support the craft community for a greener future. It was an attempt to engage with the four key agencies — craftspeople, intermediaries (craft NGOs,designers), government and the market. The response was overwhelming. So far, #handmadeinindia poster has been translated in 22 regional languages and still counting. It has been shared not only in Indian villages and cities but across the globe.

The entire process of weaving a handwoven cloth is a coming together of people, each with their own skill sets and women form an important part of this entire process.

Many artisans, over social media, shared the poster with government officials, buyers,NGOs, designers and, of course, craftspeople in their community. Many consumers and new supporters were convinced of handmade and shared it on their social media. Craftspeople responded saying it has boosted their morale and confidence.

This campaign has helped build solidarity across states within the craftspeople and the craft community at large.

For centuries, the handloom weaver has continued to work from home, offering the world the choice of a conscious living which is sustainable, local and green. Vriksh has been collaborating with the weaver community by making this conscious lifestyle choice. The dialogues with weavers have given me hope and conviction to carry on my journey in the handmade sector.

This piece is a part of our special issue on Art in the time of Pandemic, curated by critic, author and one of our contributing editors, Ina Puri

More from Arts

Comments

*Comments will be moderated