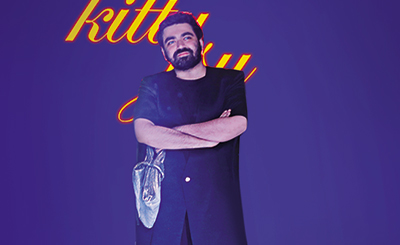

R Madhavan and Surveen Chawla in a still from Decouple

Manu Joseph’s web series streaming on Netflix is an illuminating meditation on relationships, with a calculated dose of hilarity, felicity and depth

Manu Joseph’s web series streaming on Netflix, Decoupled (2021), starring Ranganathan Madhavan and Surveen Chawla, is an illuminating meditation on relationships, with a calculated dose of hilarity, felicity and depth. When a marriage hits the rocks, it is not always life in shambles, but a renewed hope in companionship that can stem the tide of acrimony, hatred, anguish and disorientation. I am reminded of an ironic U-turn expressed in the American poet Tony Hoagland’s poem, ‘In Praise of Their Divorce,’ where the poet-persona says: ‘And when I heard about the divorce of my friends, / I couldn’t help but be proud of them, /that man and that woman setting off in different directions, /like pilgrims in a proverb.’

Joseph’s seductive spell of ironic humour, when it ploughs through the absurdities of human behaviour, can be dizzyingly thoughtful. The sweeping generalisations, thanks to entrenched ideas around patriarchy, hypocrisy and toxic masculinity, are hurled at all and sundry and spewed with impunity, getting the most eyeballs. Pointed, outrageous, sensuous, cerebral, and a lot more! The language of Decoupled is beyond the pale sometimes; however, the snatches of moments, where the truthfulness of a relationship is not compromised, are enduringly redeeming and glorious enough to testify to the beauty of goodness, mutual trust and love. The eight episodes of Decoupled add depth to the debate on wide-ranging issues from marriage to misogyny, from patriarchy to parenting, from sexuality to spirituality, from adultery to altruism, from transgression to transformation. What burns bright is the sardonic humour deployed with care and ease.

Arya Iyer (Madhavan) and Shruti Sharma (Surveen) are couples who love and fight with undying belligerence. Their witty duel is a reminder of the creaky institution called marriage and its dwindling value. Deep down, both Arya and Shruti are aware of the ethical and emotional implications following their imminent ‘divorce’ on their twelve-year-old daughter, Rohini. When they humour one another, they are loveable and adorable; when their cajoling tricks fail, they face up to the prickling realities of life. The conflict between Arya’s empathetic interior vis-à-vis his playful exterior is riveting at many levels — visceral, cerebral and ethical. Both Arya and Shruti have their aspirational muscles to flex and cherish sexapades to be secretly blissful. They strive to embrace their individuality; their egos are not full-blown though. Their egos do not flare up as they are not tied to any authoritarian syndrome.

Ironic humour surges through the arteries of characters. Shruti is bold, beautiful and endowed with a fierce spirit of freedom. Compared to the level-headed Shruti, Arya is a writer who is impulsive, naïve and given to shooting from the hip. He lacks Shruti’s quality of discretion and has to spit out the truth no matter how unsavoury. Arya’s idiosyncrasy is ludicrous and he conjures up Ayaan in Manu Joseph’s Serious Men (2010) in as much as they both are brutally honest in jarring viewers into wise wakefulness feeling rather embarrassed but, on second thought, alive to the truth, hitherto cornered by clinging to the clichéd, let-the-sleeping-dog-lie attitude to life. Dr. Basu, hiding behind his projected sanitised image, is a cynical pessimist hell bent on bringing disgrace upon Arya. If he is mean-spirited, it is because he is wedded to social conditioning making him the butt of ridicule.

Writers are not spared either. Both the writers, Arya and Chetan, are at loggerheads, each trying to outsmart the other by witty repartees and below-the-belt hits. They flaunt themselves as cult figures of Indian writing unmindful of the ‘not-so-literary’ pot-pourrie they churn out. They both have an imposing sense of superiority and self-image and poke fun at their dogged commitment to self-serving agendas, the mores of contemporary life of writers-as-celebrities and their foibles to the point of dripping absurdity. Their jealousies, pretences, airs and graces are but natural; they are also affable and accessible to one another. They ride high on their inconsistencies bringing out antagonisms and power-struggles.

Decoupled opens up a critical approach to life, ideologies and human relationships. What Manu Joseph does with panache is the stylistic rarefication when it comes to tapping into the shades of humour. Moreover, the idea of ‘decoupling’, the smart euphemism for divorce, does not evoke bitterness, anguish and despair. The idea of staying together under the same roof and yet claiming to snap out of a world where each partner values wellbeing exudes freshness. Decoupled floats this beautiful concept of coupledom, a relationship where ideological differences are not sacrificed at the altar of so-called social norms. Both Arya and Shruti wish to explore their free rides to the world of fantasy with no strings attached, no emotional or mental burden to shoulder. Decoupled is iconoclastic for marital relationship was never so ‘unique’ where couples could be strangely apart yet snugly attached. Is that not gloriously humane, I wonder! In this whole process, the phoney aspect of relationship is exposed. It is also a searing commentary on what lies disguised as ‘true love’.

The erotic oomph in Decoupled is lyrical and is not reduced to obscenity or trivialised to cater to shoddy tastes; what sustains the spirit of the carnal is the meticulous sense of timing that renders situational ironies worthy of note. The grammar of irony is dealt with deftness and, contrary to amplified or forced inconsistencies, the natural unfolding of opposites clashes with an unmistakable streak of cognitive value contesting deep-seated prejudices against marriage and relationships. The high society, starched with monstrous hypocrisy, lachrymose sentimentality and disguised as empathetic catholicism, is hit hard. Uncritical acceptance, the fount of mindless acrimony and abuse, is rubbished by Joseph and his brand of scathing satire, biting wit and light-hearted banter.

Joseph is tirelessly observant in putting ‘humour’ to good use. The humour is genial, fluid, vibrant, sarcastic and what not. Let me mention a few wacky situations. The baby-faced Masha (Sonia Rathee) swoons over Arya and then flies into a rage when Arya blurts out the idea of physical intimacy for money, inviting her wrath. Amidst a horde of guests, the hot cast-iron humour sizzles when the bride-to-be is woefully disappointed to find the momentous moment ruined by the ham-fisted Arya. Against the ritualistic intoning of ‘wah, wah!’, comes another situation, hilarious to the hilt. The driver Ganesh’s act of naïve candour, egged on by Arya, ruins Basu’s artistic masterpiece; the humour is generated in the clash between anticipation and apprehensiveness. The unexpected turn of humour is tellingly precise as viewers stomp right into the puddle of ironic humour splashing the muddy water on the torrid nerves of audiences. This is a bloody massacre of genial humour delivered at white heat! The silence of Dr. Basu during his interactive installation drives the impatient driver Ganesh nuts; Ganesh, unable to rein in his annoyance, unleashes his savage fury by striking Basu hard. A great sense of tension is released; the ‘amazing’ banana is peeled off and devoured by Ganesh with a sense of triumph. The nonplussed audiences, gasping in disbelief, cast blank glances as the situational humour unfolds so perfectly. The oblique, comical allusion to the artwork of the renowned Italian artist Maurizio Cattelan at Art Basel Miami Beach, a banana duct-taped to a wall that sold at a whopping $1,20,000, is a comment on what is art, how it is ‘projected’ as ‘art’ and how the popular culture buys into it. This overlap of incongruity is parodic through the deployment of two ingredients, exaggeration and nonsense, evoking unmitigated sneering. Don’t ever say, ‘The humour is just not landing!’ It landed with a majestic bang! Another side-splitting incident is Arya interviewing the maids thinking them as eunuchs. One can hear ‘humour’ through the abuse of language as puns and allusions augment the slippery slopes of this slapstick comedy; not to forget here the mercurial Madhavan at his best!

Purists might scoff at the ‘handshake’ episode with a prickle of disgust. Blame it on Arya’s obeisance to obsessive mannerism, he is unable to fight off. Arya’s morbid fear of touch in this case is not out of contempt but a sign of his psychic inhibition. So, why make a fuss over this! Hope the gang of stop-watch critics, baying for Joseph’s blood, understand the subtleties of comic uncertainty in Decoupled. Another contestable issue in social media, thanks to skewed interpretation, is the prayer scene that rationalises personal space in different religious contexts. Joseph emerges as a discerning integrationist, not a peddler of bigotry. To dismiss this truth is to throw the baby out with the bathwater.

Decoupled is a radical text offering the wisdom of hindsight by identifying what is institutionalised and how it induces ideological rigidity. It also offers a relationship-formula through the novel concept of ‘decoupling’ as an antidote to salvage a grossly asymmetrical relationship. It grapples with the pressing issues of marital and parental conduct with its raw crudity, empathy and psychological depths. Joseph packs quite a punch in this post-modern parable of the fallen state of man and woman. The series does not end with the couples walking out on each other, but the warring couples in the closing conversation are found intimately engaged in the enchanted intrigue called marriage and its unexplored trappings. As they appear sure that their paths would diverge, they are also ironically aware of the sanctity of relationship with an upsurge of anxiety, compassion and care for their fragile, pampered, anxiety-ridden Rohini and her traumatised well-being in the wake of parental separation. Besides the idea of absent parents, their conjugal affection is not shallow to drive them apart. Shruti cannot shed herself of Arya and Arya cannot shed himself of Shruti either. Their hunger, both consciously and intuitively, for each other never dies down. This reciprocity is unyielding and acknowledged without any vestiges of ego; decoupling becomes an offering to spare their only shell-shocked child the suffering of mental agonies. In the final analysis, both Arya and Shruti have reasons to feel good about their Samaritanism. Joseph loathes seeing the sanctity of parent-child relationship, man-woman relationship desecrated. This is radical in thought and Decoupled unearths what is ‘unseen’ in the ‘seen’ banality of human existence without any arcane ornamentation and the absolute human capacity for depravity, hypocrisy, sexual betrayal, and falsehood. What redeems the excesses of inconsistencies is the satirical humour that boils over its boundaries, exposing the maladies of the modern world — perversion of stereotypical thinking, ruthless self-centredness of the so-called educated class, reductiveness of human emotions, lack of accountability to cultural inclusiveness, and more importantly, lack of receptiveness to ‘humour’.

Scripted with a discerning eye to the human psyche and human goodness, Decoupled is refreshingly vibrant, provocative and nuanced. No matter how you slice it, Arya and Shruti are in conjugal love! When the series ends, the lovey-dovey dilemma of Arya and Shruti is not dissolved. They seem to be haunted by DH Lawrence’s Ursula’s existential angst: ‘Why aren’t I enough? ‘(Women in Love) only to renew their bonds of togetherness. The ending inevitably carries a smell of an extended narrative of ‘decoupling’ and its contestatory politics. Joseph makes ideological, cultural and emotional investments in his amazing and blasphemous Decoupled. As viewers, we sniff a sequel on the cards, no?

Manu Joseph’s Decoupled critiques the systemic nullification of ‘humour’ as a bedrock of human experience. He creates a dawning awareness of humour. It is humour, retrieved and redeemed in all kinds of discourses. Championing the peripheral position of humour, Joseph is also proffering humour as a motif of meditation, a mode of thinking against the ambiguity and complexity of the human condition.

More from Culture

Comments

*Comments will be moderated