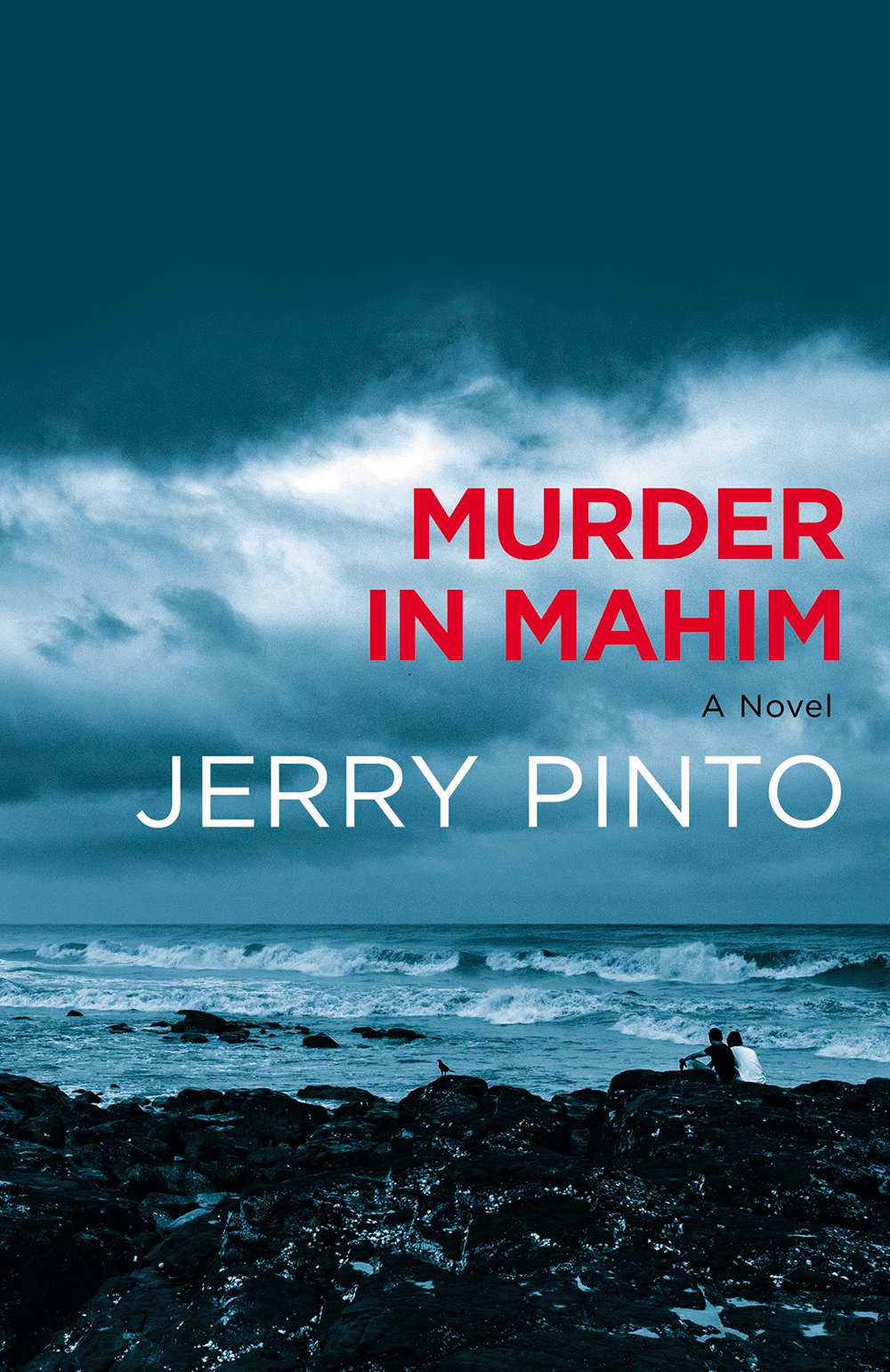

Murder in Mahim, Jerry Pinto’s new novel, a murder mystery set in Mumbai, is a story of family and friendship. It’s a compelling and poignant exploration of loneliness, greed and unlikely solidarities in the great metropolis. An excerpt from the novel, published by Speaking Tiger.

He was on his way to Andheri in a train when Jende called.

‘Come,’ he said.

There was something in his voice that made Peter get off the train at Bandra and head straight back to Mahim.

‘Sit,’ said Jende. ‘Tea? Coffee? Something cold?’

There was an awful formality to the Inspector’s voice.

‘Trouble,’ thought Peter, ‘I’m in trouble.’ He was immediately ashamed of himself. This was the standard knee-jerk response to the police. He tried to quell his frightand-flight reaction.

‘No trouble. Sorry, I meant, please don’t trouble,’ said Peter. Then to hurry things on, he said: ‘Say.’ He was aware of the bareness of this and opened his mouth to add something but he couldn’t think what.

‘You are my friend. Millie-tai is also…’

Jende shrugged to indicate that he was aware that while Millie fell short of being a fond brother’s or friend’s wife, a

bhabhi in the way Bollywood’s scriptwriters represented the species, she had her place in the scheme of things.

‘And Sunil…’ he added.

Peter’s heart froze.

‘For small matters, we can do something,’ Jende said. ‘But this is a big matter. This is murder.’

Peter could take it no longer.

‘Sunil…he’s not…?’

Jende looked confused.

‘Sorry? What?’

‘Sunil’s not hurt?’

‘Hurt? No. One minute, one minute. What is it you’re thinking?’

‘He’s not been home. He’s not been in touch. I thought he might be…’

Jende’s face went expressionless and Peter learned another lesson in physiognomy. You might think friends did not show much expression but when they chose to clear their faces of all indicators, you saw another face entirely. This was a familiar face, one he’d seen across decades, but this was the first time he was confronted with the professional Jende. He could see why this would be a useful skill. With no expression on one face, the other face in a conversation would fill with emotion. It was the same way with interviews; if you used silence as a tool, it could provoke potent comments simply out of the other person’s desire to fill the void.

‘Not in touch? Out of town? Since when?’

Once again, there was no disbelief in Jende’s tone.

But there was nothing else either and so the disbelief was apparent.

‘I don’t know,’ said Peter and wished this did not sound so lame. ‘Well, he was in town on Sunday.’

‘And this you know how?’

‘There was that demonstration.’

‘What demonstration?’

‘Against Section 377.’

Jende’s face became a zen garden of receptive inexpressiveness.

‘Achha? He was there? He told you?’

‘Tell us?’

‘They are like that,’ Jende said, father to father, but there was a touch of professional commiseration in his manner.

He’s playing me, he’s playing good cop, thought Peter.

‘I saw his photograph in the newspaper.’

‘Ah,’ said Jende. ‘After that?’

‘Nothing.’

‘He does this often?’

‘I don’t know. Yes. Often. Most of the time,’ said Peter, miserably aware that he sounded confused.

Jende gave him a moment and then said: ‘Which one?’

Peter tried to collect his thoughts.

‘Most of the time I know where he is. But sometimes he takes off. To help someone with a project. Or he’ll go to a

village. Or he’ll be at a friend’s home, overnight.’

‘Just like that?’

By which Peter understood Jende to mean: doesn’t he need to ask your permission?

There had been pitched battles over this. Sunil maintained that he was an adult. Millie agreed and said that adults

had responsibilities and these included informing those whom they loved and those who loved them about their

whereabouts.

‘And when-abouts and why-abouts and who-abouts and what-abouts.’

‘Don’t talk nonsense, Sunil,’ Millie had said. ‘I don’t ask all the details.’

A temporary truce had been declared after Sunil agreed to share his timetable with them and granted them the right to call if he had been out of touch for an unreasonable amount of time.

‘Only who is to say what a reasonable amount of time is…’

‘If you are going to be two or three hours later than the time we expect you.’

‘What time do you expect me?’

‘How can we expect you when you turn up whenever you want?’

‘That is exactly like giving me a curfew.’

Page

Donate Now

Comments

*Comments will be moderated