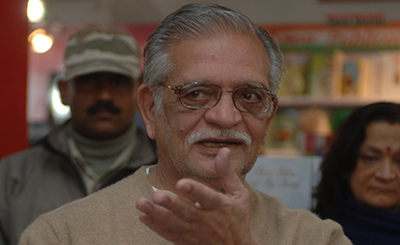

Sarvat Hasin. Photo courtesy of the author

Sarvat Hasin was born in London and grew up in Karachi. She studied Politics at Royal Holloway and later Creative Writing at the University of Oxford. Her second book, You Can't Go Home Again, is a collection of interlinked stories that draw a powerful portrait of young Pakistan, at home and in the world.

A group of teenagers in a Karachi high school put on a production of Arthur Miller's The Crucible — and one goes missing. The incident sets off ripples through their already fraught education in lust and witches, and over the years, the young men and women grow up together and apart, haunted by both home and djinns.

In this interview, Hasin talks about her two books and the universe they spring from. “I think I have always loved books the best where I could see myself in them — not because the circumstances of a character’s life exactly matched mine but because of the emotional truth. That’s what I aim for, to make these stories specific enough that they get to some universal core,” she says. Excerpts from the interview:

Kausambhi Majumdar: Your debut novel, This Wide Night (2016), told the story of four sisters in Pakistan, narrated by one of their neighbours. Your latest, You Can’t Go Home Again, is a collection of seven interlinked short stories, and marks a shift in form. Which format are you more comfortable in?

Sarvat Hasin: I think format needs to be the right vessel to fit a story in. I can’t imagine trying to fit the events of This Wide Night into a fragmented book like this one — nor can I imagine streaming this book to a three-act structure. One of my tutors at graduate school would talk about matching the tale to the teller: the way you tell the story should define and enhance the narrative. I wanted You Can’t Go Home Again to feel like a building with many rooms that you wander through and glance in at these people’s lives which is a very different feeling to This Wide Night where you follow these characters through their lives, with each of them coming of age around you. With this one, I wanted bursts of energy instead of a slow burning flame.

Kausambhi Majumdar: You Can’t Go Home Again starts off with a high school production of Arthur Miller’s The Crucible, which is a play based on the Salem Witch Trials. As the book progresses, witches and djinns become significant plot devices. Did The Crucible inspire this book? Or did you incorporate this play because you were writing stories revolving around supernatural elements? How did you conceive these stories?

Sarvat Hasin: The Crucible wasn’t so much as an inspiration as an indication of where the narrative is going: I wanted it to softly introduce those ideas. I also look back at theatre in school with a lot of tenderness. I think putting teenagers in a play is always a fantastic way to build tension.

Kausambhi Majumdar: How do you get an idea for your story? Is it an image, a thought, or an episode?

Sarvat Hasin: Each of these stories started differently. A Night Full of Cheap Stars came from wanting to talk about the television industry in Pakistan. Pakistani dramas have really grown in the last few decades and the actors have become household names, wrapped totally into the conversations and trends of the country. It didn’t always used to be that way — when I was a child, a lot of the media we consumed was imported. I wanted to explore the connection with homegrown storytelling.

With others, it is sometimes an image. Socks was a collection of images: children playing in shopping trolleys, cricket on a quiet street, school uniforms and white socks. The real freedom of stories instead of novel chapters meant I could follow these ideas, chase them down the rabbit hole with a freedom that a novel rarely affords.

Kausambhi Majumdar: In You Can’t Go Home Again, each of the characters is dealing with personal traumas: heartbreak, unexplained disappearance of a parent, unexplained disappearance of the self, death. And each of them has repressed these distressing events within themselves. Across the seven stories, we observe that this repression leads to a psychosis that manifests in the form of djinns. Also, the stories end in cliff-hangers. A reader finds it hard to distinguish between the real and unreal as do the characters. Was incorporating the supernatural elements a way for you to symbolise these personal demons?

Sarvat Hasin: I think of the supernatural in the book as divided into two bunches of characters: the ones who wield it and the ones who come up against it. Shireen, Rehan and Karim are all confronted with these elements at different points in their lives while characters like Maliha and Naila seek it out. I wanted the supernatural to manifest through superstitions, building in each story in an anxious way — each of these characters is either taking control of their desires or running away from them and the supernatural seemed like an interesting way to tangle that.

Kausambhi Majumdar: Your writing style is quite distinct. Dialogues blend in with the descriptions. There are no markers to indicate an ongoing conversation. Tell us what made you choose this style.

Sarvat Hasin: I want things to feel closer, not to jangle with the readers’ perspective but to embed them in the story more.

Kausambhi Majumdar: Your first book, This Wide Night, was marketed as “Little Women meets Virgin Suicides in Pakistan”. Do you think when an author indicates that their stories are influenced in part by a literary classic, there is a pressure to live up to that particular classic? Does it distract readers from the originality that the writer has tried to infuse in their reimagined novel? Do you think this makes the writer’s work reductive since readers would be constantly comparing with the classic?

Sarvat Hasin: I didn’t really think beyond the structure of those stories when I was writing. It’s interesting because in some ways those references seem helpful as a debut writer — when nobody knows you or your writing, it seems like a good indicator of what you’re trying to do. Those two influences in particular seemed so far apart in my mind that I found it hard to imagine that people would think that I was taking on and reinventing either!

The truth is that all stories come from somewhere. I write because I love to read: I consume books and movies with a ravenous love and it’s true that I am always comparing stories against each other so I understand the impulse to do the same with my work.

Kausambhi Majumdar: Do you have any specific type or set of readers while writing any story?

Sarvat Hasin: I send things to my writer’s group, to my agent and to my close friends. With this collection in particular, I wasn’t really thinking of a publisher or reader — I was writing things to entertain myself and my friends.

I think I have always loved books the best where I could see myself in them — not because the circumstances of a character’s life exactly matched mine but because of the emotional truth. That’s what I aim for, to make these stories specific enough that they get to some universal core.

Kausambhi Majumdar: In You Can’t Go Home Again, the characters are distant the political discourse and current affairs of the country. In one of the stories, one of the characters, Karim comments disdainfully about the general state of the country, but his mother reprimands him for talking like that about “home”. Is this an indication of a general change in the attitudes of the youth of today in the Pakistani society from the attitudes of the previous generation towards the internal conflicts of the country? Or is this only a trait of Karim’s character because he is detached towards everything in his life?

Sarvat Hasin: It is not intended to be anything more than a trait of Karim’s character. Certainly there is much discussion in both Pakistan and India of the brain-drain — people who are educated abroad and settle there instead of bringing their skills back to South Asia. But there are also plenty of people who do return, either because of their circumstances or their desire to give back.

Kausambhi Majumdar: Generally, there are certain expectations from readers when they pick up a book from a writer from a region that has been in news for its political climate. The stories in both You Can’t Go Home Again and This Wide Night are based in Pakistan; however, they do not directly engage with any political or historical events of the country. Do you feel the urge to incorporate themes of geopolitical conflicts, identity, and representation in your books?

Sarvat Hasin: I think a book in which characters did nothing but talk about politics or the weather very dull. History happens to people; they are living it and I want to write about people’s lives. Certainly, neither of these are intended to be apolitical books — everything about the character’s decisions and choices, their ability to move through the world, the djinns they either believe in or don’t and even their choices in who to love or not to marry Is deeply political. All these things are laced through with their specific set of circumstances.

Kausambhi Majumdar: In both the books, the characters are not deeply engaged with the cities (Karachi, Lahore, London) they are in. The stories have a sense of versatility in terms of setting, they can happen anywhere. How crucial is the setting or geography to your stories?

Sarvat Hasin: Very crucial. The way a story unfolds is almost entirely determined by where it is set. Naila and Karim’s relationship is completely determined by living in Karachi — how they meet, the timeline of their relationship, the specific pressures they both feel would not exist if they were characters who were born and lived somewhere else. I think the city is not just a physical space but an emotional one.

Kausambhi Majumdar: In This Wide Night, you have written the story in three acts. While the second act is a third-person narrative, the other two are first-person narratives. And in You Can’t Go Home Again, the title story is a second-person narrative while the remaining six stories are third-person narratives. Was there an intent behind mixing up these different forms of narratives or was it something that developed organically with that particular story or act?

Sarvat Hasin: I love the second person voice for the tone it brings, a certain accusatory remove. Karim in that story is alienated from himself — I wanted the remove to highlight that feeling. In the other stories, we see him through the eyes of women who love him, who think of him as placid and comfortable. I wanted this story to get closer to the core of him while still holding him at an arm’s length, to feel the haunting in him.

It was similar with This Wide Night. I think of changing persons as a way of shifting the camera’s focus, to shift your perspective of a character.

Kausambhi Majumdar: Who are your literary influences? What kind of stories do you draw from most?

Sarvat Hasin: My favourite writers are probably Junot Diaz and Helen Oyeyemi. Recently, I’ve read and really enjoyed Too Much and Not in the Mood by Durga Chew-Bose. I’ve also been really loving poetry, particularly Kaveh Akbar and Hera Lindsay Bird.

Kausambhi Majumdar: What are you working on next?

Sarvat Hasin: I’m working on some other forms: essays and poetry but also writing a new novel.

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated