Jatin Bhatt sat in the garden swing taking in the morning air, sniffing once in a while at his wife Drishti’s panties, gray lacy cotton he’d fished out of the laundry basket not ten minutes ago.

Two more days and Drishti will move out, three weeks after their daughter’s eighteenth birthday. They hadn’t spoken a word to each other in the last two months, ever since they decided on the separation. So much for an ‘amicable’ divorce.

Taji taji sabjiyaan, came a call from the street. Seated at the gazebo his wife had designed between flowering shrubs, Jatin couldn’t see the gate. The swing creaked beneath his weight, breaking up the tinkle of the fountain behind him.

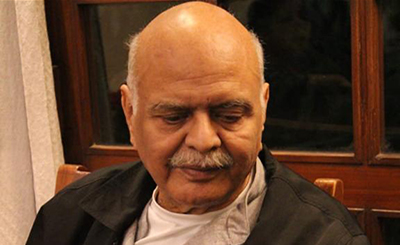

Giddy lasses ought to wait for their lovers on this swing. This pansy garden didn’t need a potbellied man. He stared down at his old blue overcoat, and even after he’d taken off his thick-rimmed glasses, he saw a sad old pervert sniffing discarded underwear.

Taji taji sabjiyaan, the man sounded much nearer now, his voice roughened through smoking and endless hawking of his vegetables. Jatin knew this old-timer, had seen him push his cart around the last two decades, kicked his puny butt a few times in his years as a police constable, when the man didn’t cough up his hafta on time. And now look at the bugger; the Indian government had recognized his kind, passed a law to protect his rights. No wonder the old man’s voice rang out, demanding customer attention instead of requesting it. Jatin had to smile at that rousing, peremptory call.

Why do you want to buy from him? Drishti’s voice floated out the main door. Jatin peeked around the corner and spotted his wife’s skinny butt in her nightgown, standing behind their old housekeeper.

We need vegetables for lunch, Madamji, the housekeeper wiped his forehead on the towel that never left his shoulder, the cauliflower in the fridge is spoilt.

God knows what dirty sewer those came from, Drishti pointed at the cart, and continued in her loud, convent-accented Hindi, we buy organic from the mall, you know that.

Never marry a woman based on the way her butt looks in a saree. It doesn’t stay the same, nor does the woman. Too late for that lesson now. Wholegrain, organic, low fat, Fitness First — words that had broken his marriage as sure as his sleeping with other women, and inability to quit smoking. Ma didn’t know these words, and even though Papa slapped her about every now and then and the two bickered like stray dogs over a scrap of bread each night Papa spent outside, they stayed together. Ma didn’t leave Papa, not till the very end.

An Indian wife never left her husband, an Indian marriage meant forever. Not any more. Drishti will leave him soon.

But Madamji, no time to go to the mall right now, the housekeeper’s hands had now gone to his hips, I need to pack sir’s lunch. Jatin liked how ten years in a Delhi household hadn’t taken away the Lucknowi tones of his housekeeper’s Hindi. That’s how you kept your heritage: each detail dwelt on, every nuance preserved.

I don’t care what you make for your sir, but don’t feed my daughter all that garbage. Drishti turned, her hands smoothing back her boy-cut hair. Make her some quinoa the way I taught you, and use frozen vegetables.

Jatin balled the panties and fisted them into the pocket of his overcoat. He’d loved running his fingers through the curtain of his wife’s hair as she moved over him on their bed, and one day, just like that, she’d gone and got it chopped. Slowly, she’d given up the sindoor, and the mangalsutra. How did she expect to be recognized as a married woman?

Bhabiji, my vegetables are fresh. The hawker tried to call her back, his Hindi tinged from hinterland Bihar. Bhabiji, he called her, brother’s wife. That man knew she was married, recognised her.

Ma used to buy carrots from this fellow come winter and made Jatin the smooth, melting-soft gajar ka halwa that burst in his mouth in caramel sweetness. In summer the cart brought unripe mangoes, and Ma laid out the pungent, spice-laden aam ka achaar. They didn’t make women like Ma any more.

Jatin sighed, both his hands in his pockets, leaning against the cracked walls of his bungalow. Drishti didn’t turn back, striding in through the main door, her head probably buzzing with décor ideas for her company, or the parties she would go to post separation. Closing the gate, the housekeeper followed his mistress.

Arey, take the cauliflower, the vendor pushed his cart further towards the gate, I give you good price. It’s crunchy and white, look, you can cook the stems, too.

Tomorrow, the beat constable would shove this man if he didn’t hand in his hafta. The new law still sat on paper. By the time the New Delhi Municipality enforced it, the office babus will figure out new ways to tax this fellow, and money still trickle up the pockets of the police all the way up to Commissioner Jatin Vohra. Loopholes of bureaucracy will strangle this man, and then he’ll get squashed out by shopping malls.

The hawker turned his cart and trundled off, his shoulders slumped.

Jatin stepped out to call the old rascal and buy his cauliflower. What was his name? Jatin tried to shout Bhaiya, the Delhites’ term for any man they met on the street. Jatin didn’t say it, though. Bhaiya, though Indian, sounded rural, uncouth. He must quit his old-fashioned ways.

He rushed to the gate, but the old hawker had walked out of earshot.

Jatin didn’t want to be late for his office. On the way back in, he binned the contents of his pocket — the empty cigarette packet, the Nicorette, the panties. He dusted off his hands and took the stairs, two steps at a time.

In the distance, the old man’s call rang out again, but Jatin paid him no mind.

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated