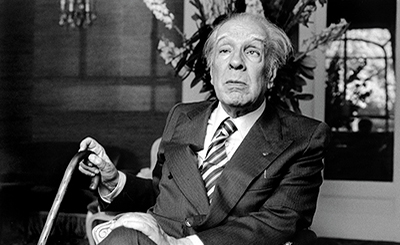

Qurratulain Hyder’s work is intensely political and often prescient: Saleem Kidwai. Photo: Kabeer Kidwai

The translator of Qurratulain Hyder’s second novel, Ship of Sorrows, on how Partition is a recurring theme in her fiction — from her first novel Mere Bhi Sanam Khane to her last, Chandni Begum

Saleem Kidwai, 69, is the only one, apart from the author herself, who has translated Qurratulain Hyder’s novels. Educated at the University of Delhi and at McGill University, he taught medieval history at Ramjas College, University of Delhi, before he volunteered for early retirement. He is now an independent scholar. He has edited (with Ruth Vanita) Same Sex Love in India: A Literary History (Penguin, 2000). He has edited and translated the memoirs of Malika Pukhraj, Song Sung True: A Memoir (Zubaan, 2007). He has also translated the short stories of Syed Rafiq Hussain (1913-1990), an Urdu writer, poet and critic.

In this interview, Kidwai talks about how Hyder, whose work is intensely political and often prescient, was a path-breaker as far as Urdu fiction was concerned, how she abandoned the linear narrative and introduced modernism to Urdu literature. “She was inspired by the modernists and was confident enough to experiment with new styles while still very young. Poetry and fiction existed side by side in her work,” says Kidwai. Excerpts from an interview:

Shireen Quadri: Ship of Sorrows (Women Unlimited, 2019), Qurratulain Hyder’s second novel, evokes the elite Muslims’ dilemma in the wake of the Partition, the question of whether to leave or whether to say. How do you see the novel, and its overarching theme, in the larger context of Hyder’s exploration of the wounds inflicted by the cleaving of land, and hearts, and the choice of the Muslims in the country which they chose not to leave?

Saleem Kidwai: The Partition is a recurring theme in Qurratulain Hyder’s fiction from her first novel Mere Bhi Sanam Khane (1954) to her last, Chandni Begum (1989). This is not at all surprising because it had impacted her personally. She had witnessed mob rioting that preceded the Partition and had seen her father’s house being torched in Dehradun, and then chosen to migrate. That she constantly returned to it is also because she was deeply interested in politics and history. In Mere Bhi Sanam Khane, a group of idealistic elite young men and women are confronted with the painful impact of partition both in terms of physical loss as well as a loss of their world. In Ship of Sorrows, written five years later, a similar group of people have to live not just with the disruption of the world as they knew it but also the realities of a new world, of new nation states. Both those who stayed as well as those who migrated discover worlds they had not bargained for. The choice of whether to stay or move was also not a simple one, the decisions often being made by circumstances or by others. The non-Muslims within this group of close friends who don’t have to make this choice, also find their realities altered by the decisions of others. The new militarised nation state is no longer recognisable to those who stayed for they sense the underlying hostility based on their religion. These are both stories of personal experience also. She had not got over the trauma and so she continued to write about it. One complements the other.

Shireen Quadri: The novel, like many other works by Hyder, blends the personal with the political. Her first novel, Mere Bhi Sanam Khane, was set in Lucknow of 1940s and dealt with the idealism of the youth and the young’s fight for a new world order after the old order begins to fall apart, following Partition and Independence. Like Mere Bhi Sanam Khane, do you see this novel as essentially an exploration into the life of the mind, and the choices before an artist: how to make art? How to live life?

Saleem Kidwai: Very much so. This novel, too, is based in the 1930s and the 1940s when the members of this group of friends are going through their intellectually formative years. The two most influential members among this group of friends are creatures of the mind. They write prose, plays and poems, paint, perform in plays and dance. They struggle with their art, its place in the changing world, but the novel is more than that. It also delves into where they fit into the civilisational history of the sub-continent. How they have lived their lives till then and how far their lives are influenced by developments far larger than their own choices in the same way as their art was the product of intellectual and artistic forces far larger than them. The choices before them are based on how they grapple and understand their own history. Hyder belongs to the same age group as her characters. She is also writing herself and her place in the larger scheme of things over which she has no control. It is always the bourgeois mind — that which she understood and connected with. She was criticised for being bourgeois but she stayed honest to herself.

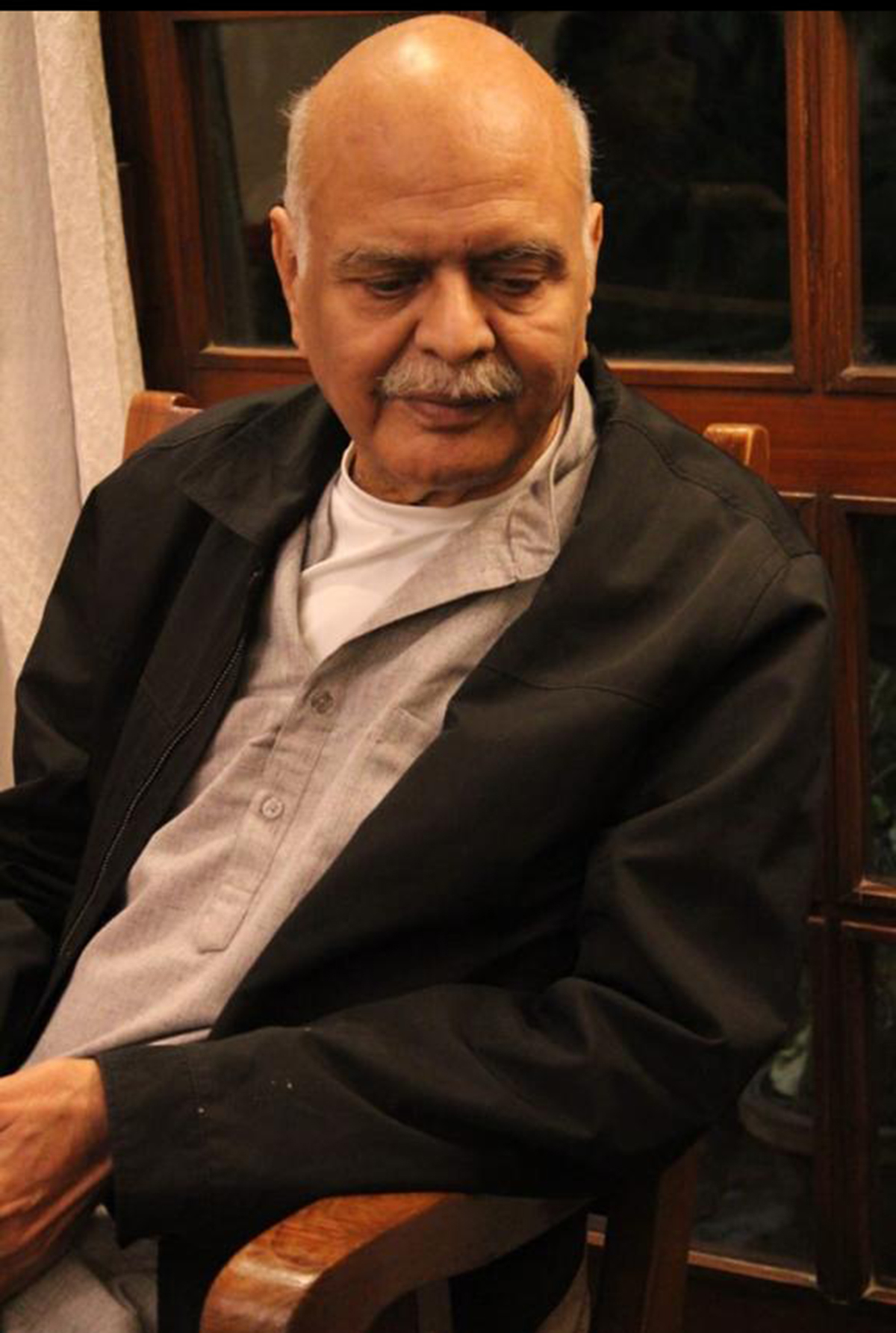

Qurratulain Hyder. Photo courtesy: The Nation, Pakistan

Shireen Quadri: Yes, the novel is not strictly fiction in the sense that Hyder picked a lot from what was happening to her and those around her when she was writing. The novel is, in fact, memoir in parts. Do you see Hyder’s life and times inevitably finding their way to her art? This is with many writers — directly or indirectly.

Saleem Kidwai: The novel is many things. It is fiction, it is memoir, it is a documentary, it is a flight of imagination, it is art, it is poetry and it is experimenting with style. She peoples it with real people to give her story authenticity and immediacy. She draws on her family history. Hyder’s work has always been a melange of her imagination, the reality and history. By creating a complex structure where she is not just the narrator but also a character in the novel she can both tell a story, comment on the context on which it is based and also gives her space for self-reflection through interior dialogue which makes the novel extremely rich. Her work is intensely political too and is often prescient.

Shireen Quadri: The novel also reflects how Hyder was primarily a Modernist of Urdu literature, so assured of her craft that she was never afraid of experimentation with style. Ship of Sorrows also does away with the conventional plot and storyline of gradual progression of events into a climax. Do you see her craft and style as being influenced a great deal by the West, especially considering she translated into Urdu Henry James and T S Eliot. Also, considering her writing is replete with references to Wagner, Schumann, St Augustine, Noel Coward and many others.

Saleem Kidwai: Hyder was a path-breaker as far as Urdu fiction was concerned and abandoned the linear narrative and introduced modernism to Urdu literature. She was exposed to world literature particularly because of her father, the writer Sajjad Hyder Yildirim (1880-1943), and was personally inspired by the modernists and was confident enough to experiment with new styles while still very young. She was also bi-lingual and had studied English Literature at the university. The early criticism of her work did not deter her and she gained in confidence as she continued to experiment. The modernist definitely inspired her not only in her way of writing but also for her to introduce them to Urdu readers. Her cultural references are global which are the result of her tremendous erudition. She is a self-conscious writer. She is aware of literary trends and is eager to employ them in her art. She skillfully blends various tendencies from western and oriental cultures to create a brand which is, let us say, her patent. She had also imbibed the many cultures she had grown up with — the Indo-Muslim and the British. Through her Muslim heritage, she also had access to the pan-Islamic world.

Shireen Quadri: In your translator’s note, you write that the objective of this translation was to introduce her experiments with style and form to non-Urdu readers. Do her experiments have parallels in Urdu literature? In what ways do you see Hyder changing the landscape of Urdu novel writing?

Saleem Kidwai: The objective of my translating Hyder is basically to introduce her to non-Urdu readers because she is far too great a writer not to be available to readers in English. This acquires urgency as readership in Urdu declines, particularly in India. The range of her experiments with style and form had no parallels in Urdu literature and that is the reason she stood out and which makes it imperative that all her works be available in translation, particularly the little-known ones, like Ship of Sorrows. Her impact on the writing of fiction in Urdu (we must remember that apart from her many novels, she was a prolific writer of short stories and novellas) has mainly been in further opening up Urdu literature to experimentation and to influences from Europe and America.

Shireen Quadri: With the novel that followed the Ship of Sorrows, Aag ka Darya (The River of Fire), her magnum opus, Hyder cemented her reputation as the great Urdu novelist who had single-handedly put the spotlight on the prose, steering the focus away from poetry that had been central to Urdu literature till then. The novel was compared to the writing of Gabriel García Márquez and Milan Kundera. What do you think Hyder achieved with this novel?

Saleem Kidwai: She wasn’t the first to put the spotlight on prose in Urdu literature. Premchand (1880-1936) and Mirza Hadi Ruswa (1857-1931) were already names to contend with before her. Her contribution in drawing world attention to Urdu prose is unmatched but it would also not be fair to say she steered Urdu literature away from poetry. In fact, she acknowledged the role of poetry in Urdu literature by giving her novels titles which were mined from the work of major Urdu poets like Ghalib, Iqbal, Faiz Ahmad Faiz and Jigar Moradabadi. She made her prose an extension of poetry. Poetry and fiction existed side by side in her work.

Yes, Aag Ka Darya was the unprecedented outcome of style and technique. Its scale, too, was breath-taking. But Hyder is emphasising the syncretism and multiculturalism of the Indian citizen and layering it with the civilisational loss, the breakdown signified by the Partition. Aag Ka Darya has got the recognition it deserves not just as a novel but also for Hyder as a writer. Ideas evolve over her novels, for instance, time and place continuously play a significant part in her work. Ship of Sorrows was where Hyder experimented with these concepts before she ramped up the scale Aag Ka Darya. Her experimentalism does set her apart though again, she is not the only writer in Urdu who was experimenting. Ahmed Ali (1910-1994) and Hijab Imtiaz Ali (1908-1999) had preceded her and Saadat Hasan Manto (1912-1955) was a contemporary. Her efforts were definitely far more sustained and elaborate.

Shireen Quadri: Her last novel, Chandni Begum, which you translated in 2017, was significant since it foresaw the kind of political climate, the poison of communalism, that was vitiating the social and political realities of the country. It revolved around aristocratic families and a disputed estate with a temple and a mosque, an allusion to the Ram Janmabhoomi movement, and was published three years before the Babri Masjid was demolished. In what ways do you see Hyder’s fiction, which dwelled heavily on India’s syncretic traditions, resonating today?

Saleem Kidwai: Not just Chandni Begum, Hyder’s novels were prescient in many ways. If in Chandni Begum she anticipated the political debate and conflict over land rights in Ayodhya and brought up the vexing question of who does land belong to in a civilisation as old as India’s. In Ship of Sorrows, too she anticipates the issue of citizenship based on religion. Hyder’s work, which constantly underlines and draws upon the syncretic tradition, particularly resonates today when these traditions are being challenged for they are reminders of what has been lost, a world that could be lost.

Shireen Quadri: Who are some of the contemporary Urdu novelists you admire?

Saleem Kidwai: Among the novelists, I have enjoyed reading Intizar Hussain (1923-2016) and Khadija Mastoor (1927-1982). Of course, there is Ismat Chughtai, who is known more for her short stories rather than her novels. There is, of course, Manto, too.

Shireen Quadri: Could you name some other Urdu writers who you would like to introduce to the English-speaking world?

Saleem Kidwai: Right now, I’m translating Hyder’s Gardish-e-Rang-e-Chaman, a novel based on the plight of the upper class women in the years following the Uprising of 1857-58. It’s a very long novel, covering over a century and I have to complete it before I think of taking on any other writer for there would be no more novels of Qurratulain Hyder left to translate. However, there is Mirza Jafar Hussain (1899-1989) whose work I am also translating though his is a work of the cultural history of Lucknow and not a novel.

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated