For three years the bard has been the wellspring from which she has quenched her thirst. Three years of tramping in cruel weather have broken him. He would run from her if he could but he knows his legs could no longer carry him far enough.

In the west of Ireland you can never tell what the weather will be from one hour to the next. Sometimes the elements will shift even more quickly, so you will walk through curtains of rain and in between you will stand in the finest new-washed sunlight. You look around and the mountains behind are suddenly smothered in slow buffering mists. The teeth of the crags in front of you are sawing cleanly against a forget-me-not sky. To the sides of the road there are glens where the shale is as dark as dragon armour, and the water slinks like a sump of quicksilver. However, pass through another veil of rain and all is re-conjured. What was grey is now blue. The slopes that were glad in the breath of the morning are now bled and dour.

In the seventeenth century Cromwell, with his hatred and implacable convictions, tramped through the land with a Bible in one hand and a sword in the other. He told the Irish to get ‘to Hell or Connacht’. They were driven into this land of tricksy storms, of scoured mountains and scrubby pastures. When at last they came to the cliffs that rise above the western ocean they knew they could run no further, so they turned to eke their lives in places where even goats had trouble finding sustenance.

A man with ragged hair is walking a road of sharp stones. The wind limmers the icy waters of a loch into chipped slate peaks. His brogues are torn and his raw heels rise from the sodden leather. He has wrapped a ragged cloak of saffron wool around his shoulders, but it is heavy from the rain and he trembles. He seems to be grinning, but his lips are drawn back from his gums with fever and the chill. It is as if he has taken his pallor from the dull light on the surface of the puddles. He looks for some place to rest but everything is broken and bare here. Not one tree to sit under. This place is like a foundry of rock. He is dying and he knows it.

We will not give him a name, since he is lost to history. He will lie in this deserted pass and no one will find his body. It is the year 1660 and there are perhaps a hundred of his type wandering the roads of Ireland. He is a bitter and mournful man. You look into his eyes and the death pangs of a whole way of life, the ruin of a whole culture, stab back at you. The world has turned on him. His certainties have all been torn and scattered. He has seen the dispensations of an ancient profession forfeited by conquest.

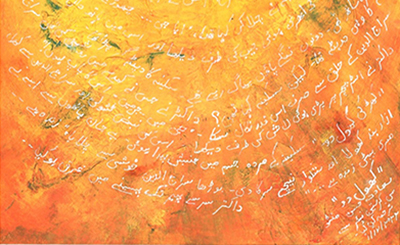

For this man is a bard: a court poet of the Gaelic aristocracy, keeper of the genealogies, satirist and craftsman of words. His time has only just passed. He remembers, as if it were yesterday, the firelight in castle halls; nights when they listened as he told the glories of his chieftain — verses embroidered with assonance, half rhyme and slanting rhyme, allusion; metres as strict as advanced trigonometry. These were the tools of his art. He was schooled as a boy in poetic forms reaching back, in unbroken succession, all the way to the verses of the druids. He can summon hundreds of poems to his tongue. They are all stored like golden vestments in the chest of his skull. He can speak Latin, French, a little Spanish and about a dozen words of English.

But now all is all cast down. The castle, where he was an honoured retainer, was smashed by Puritan canons. His chieftain is in exile. Now his poems are as useless as silk shoes on a sow. He knows of no other life, save that of his calling, and the calling of a Gaelic bard is one that the world no longer needs.

He stands on his stilty legs and wheels about in the desolation of the wild valley. He takes himself off the road and starts to climb up the slope among the boulders and bracken. In an hour he has scrabbled high up on the mountainside. He is muttering and shivering like an old crow. When he coughs it is as though some mechanism has broken in his lungs. He speaks some words to the stones, then sinks slowly to his knees. The sun is fading and the shadows are coming like dark spears along his narrow path. He lies down, still murmuring, all alone.

But he is not alone.

From the ridge above him steps a woman. She comes always at the very moment he drifts into sleep. This evening it is a sleep that even his terrible coughing will not hinder. Everything about this girl is absolute, so please forgive my recourse to old, time-worn expressions. She is barefoot. Her toes are tiny. Her skin is keenly white, like a jug of new milk left out in the rain. Her hair is dark, darker than a starless sky. Her cheek bones are sharp. Her eyes are sapphires where swims a shoal of minnow-flecks. She bends over the bard, crooning a low whispering song. Her voice is like laurel leaves hushing. Her breath is like rubbed laurel leaves. Her dress is the gleam of laurel leaves. It is the twilight — the coineascar — but her black hair makes a sudden night over his face.

It has been this way for three years or more. In ditches, in the rubble of wrecked churches, in the huts of peasants, wherever he lies down, she is there. The first night of his wandering found him on a hillside in Mayo. He had nowhere to go. In haughty dudgeon he bought oatcakes from a woman and ate them in the growing cold. He had no wood for a fire. A bard forced to tramp the roads! Such was his fury at having to sleep in the open, if his words had been sparks that evening the heather around him would have kindled and he would have flared like a beacon, whelmed by the sulphur of his own curses. He hunkered in his fringed mantle and, after hours of tossing, fretted into chilled doze.

That first time she came up from the far side of the hill. In his dream he knew this. He saw her rise from the bushes and step lightly to his side. Behind his eyelids it was a fine spring morning. She knew his name. She spoke it back to him as she told her sorrows. There was no one to care for her, she said. She was lost in shadows. She grieved in echoing glens.

‘Ochon,’ she sighed, ‘Ochon.’

He reached to brush her cheek. What age was she, eighteen, twenty? Deserted in bitter country. His finger

touched one of her tears and suddenly it was a cold winter’s day behind his eyelids. Rooks in the bare trees. She knew his misery. She spoke it back to him. ‘The English have come,’ she said. ‘I know they are felling the forests. The Sasanaigh have scattered the Princes. The soldiers of the Gael are in their graves or lost from the land. Ochon.’

At her right shoulder was a silver penannular etched with twisting spirals. She stood up and unclasped the pin. Her gown fell at her feet. He opened his cloak and she sidled along the length of him. Their flesh made a hot seam between them. ‘Give me poems, Bard,’ she whispered. ‘Make me live in this world.’

He shuddered awake to an autumn morning that promised nothing. All night he had known the secrets of the woman; the cleft behind her ear, the bow strung nape of her neck. But now he coughed among thistles. Dry mouthed and queasy, as if he had been drunk, he stumbled down the road. She was gone as if she had never been there at all, and there was not so much as a spailpín’s hut in sight.

He walked that day as if he had not slept. His feet dragging, his arms like stiff lumber. But his eyes blazed, for he had a new flaring stanza on his tongue. It had come to him fully formed with the dawn. I will render them in English as closely as I can.

The red moon hid below the hill

In the land of clan O’Malley.

They who are gone now on the waves to Spain.

It is comfort they gave me often.

I met a girl, in the wild land, straight, tall and blue-eyed,

Her forehead pale as a white banner.

Pearl shouldered —

She lay skin to skin with me.

So it was, every evening after that, as soon as he lay down she was there, whispering, softly cajoling, giving him her love and moaning as he whispered back to her his verses. He could not deny her, her fingers flickering down his back. He had no power to forbid her.

Her kisses as sharp as melt water

From the highest stream.

Kisses like a new ring of silver.

Kisses like a swan breaking the morning water

Of the loch ...

He set himself up as a teacher. For, under Cromwell’s laws, no children were to be permitted an education. With immense chagrin he took little coins, bread and buttermilk in payment from half-starved families. He attempted to teach rhetoric, Euclid and the high Gaelic poems to boys who smirked and cheeked him. He schooled them in the open air in the lee of a rock but the rain ran down his face and into his mouth. He built a hovel of sods and wattles and rocked in front of a tiny fire shedding furious, desperate tears.

Page

Donate Now

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated