Daniel Hahn. Photo: John Lawrence

British writer, editor and translator Daniel Hahn, who has translated José Eduardo Agualusa’s A General Theory of Oblivion, on the art of translation and ‘being a translator’

Daniel Hahn, 43, is a British writer, editor and translator. His translation of A General Theory of Oblivion by José Eduardo Agualusa recently received the 2017 International Dublin Literary Award, with Hahn receiving 25% of the €100,000 prize.

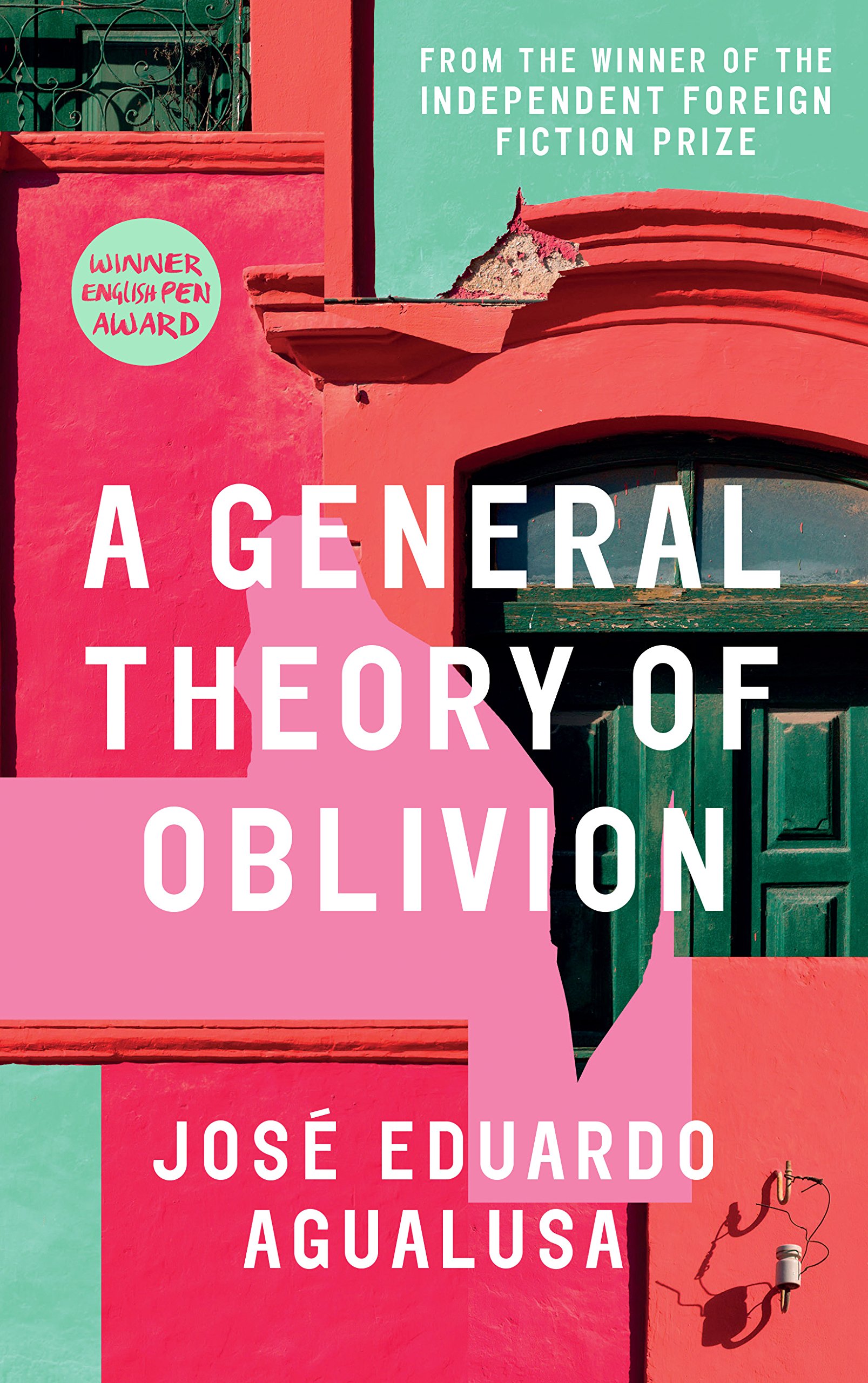

Set in Luanda, on the eve of, and during the immediate aftermath of Angola’s independence from Portugal, A General Theory of Oblivion recounts the story of an Angolan woman, Ludovica Fernandes Mano, who locks herself into her apartment with her country on the brink of independence. She attempts to cut herself off from the external world for three decades until she meets a young boy who informs her of the radical changes which have occurred in the country in the intervening years. Hahn’s translation of The Book of Chameleons, also by Agualusa, won the Independent Foreign Fiction Prize in 2007.

Hahn is the author of a number of works of non-fiction, including the history book The Tower Menagerie, and one of the editors of The Ultimate Book Guide, a series of reading guides for children and teenagers. Its first volume won the Blue Peter Book Award. His other titles include Happiness Is a Watermelon on Your Head (a picture book for children), The Oxford Guide to Literary Britain and Ireland (a reference book), brief biographies of the poets Samuel Taylor Coleridge and Percy Bysshe Shelley, and a new edition of the Oxford Companion to Children’s Literature.

His other translations include Pelé’s autobiography and work by novelists José Luís Peixoto, Philippe Claudel, María Dueñas, José Saramago, Eduardo Halfon, Gonçalo M. Tavares, and many others. A former chair of the Translators Association and the Society of Authors, as well as national programme director of the British Centre for Literary Translation, he currently serves on the board of trustees of the Society of Authors and a number of other organisations working with literature, literacy and free expression, including English PEN, Pop Up and Modern Poetry in Translation. Excerpts from an interview:

The Punch: You have translated several works by Jose Eduardo Agualusa. How stylistically different is A General Theory of Oblivion? Tell us about your first impressions when you read it.

Daniel Hahn: The style isn’t noticeably different, in that I think there’s a particular rhythm to his writing, a particular music to it that anyone who’s read him before will recognise. My aim, of course, is to recreate that same kind of recognition in whoever has read him before in English. My own first impressions when first reading this book are in some ways probably not very different to most people’s, except that I was translating it at the same time — I didn’t read the book before I started translating (that’s how I choose to work where possible) so my first draft of translating was also a process of following his sentences, meeting his characters, watching the unspooling of his stories. I read like any newly discovering reader, I just happened to be translating along the way.

The Punch: The novel is significant at the lexical level. It seems to be preoccupied with the attempt to find meaning in painful memories. But since Ludo did not speak English and had become alienated from her native tongue during the revolutionary war, her struggles with emotional isolation and cultural alienation in the text, as some reviewers have pointed out, is itself a process of translation. Tell us about your approach to translating the novel keeping the potential for misinterpretations in mind.

Daniel Hahn: It’s a hard question to answer, because I’m never really aware of my “approach” to translating a novel. I don’t plan, I don’t strategise, I don’t decide in advance what I’m going to do or try to anticipate the issues for solving. I just open the first page and start. And yes, there are in this case differences between, say, Ludo’s constrained voice and the narrator’s more expansive one, but these are things that find their way from Agualusa’s text to mine quite naturally, without ever having to deal with these abstractions.

The Punch: Does a translator’s familiarity with the landscape of a writer’s works make translating a work easier? Tell us about your understanding and evaluation of Agualusa’s works over the years.

Daniel Hahn: Yes, in many ways. The first four books I translated were Agualusa’s, then I translated twenty-something by other people before returning to him for this one, and it certainly felt very familiar and easy settling back into his writing which I know so well. Later this year I’ll be starting our sixth collaboration, and again, it’ll help not only that I have a sense of what he’s doing — what literary tics he has, what’s the pulse of the writing — but that he has an English voice now, too. His English voice should be as consistent as his Portuguese, so I don’t need to try and invent or find this — in one sense it’s already there. I know what he sounds like in English, where the springs go in his sentences, where he pauses for breath, which means much of what’s hardest about finding a voice in translation is short-cut.

The Punch: You have also translated Jose Saramago. What is your assessment of his works as a translator?

Daniel Hahn: He’s a great writer, but fiendish to translate. Mercifully, I did very little of his work, just co-translated one non-fiction book. He had two main translators, Giovanni Pontiero for the first part of his career and Margaret Jull Costa for the second, and both of them make the job seem easy and natural. Trying to make his winding sentences work naturally in English was beyond me, I fear…

The Punch: Could you tell us about some other Portuguese/Brazilian writers you’d like to translate.

Daniel Hahn: There are so many interesting Brazilian writers I’d like to get my hands on. The Granta Best Young Brazilian Novelists a few years back identified twenty writers aged under forty, and there’s a lot there still waiting for the Anglophone world to welcome them in. For that collection, I translated short work by two of those writers, Antonio Prata and Cristhiano Aguiar, both of whom deserve full English-language books; there’s another on that list, Julián Fuks, who’s bound to be discovered by the English-speaking world before long. And there are a lot of Brazilian writers I have already translated but of whom I’d like to do a lot more — I’ve done one extraordinary short novel by Zulmira Ribeiro Tavares and would love to do a second, I’d like to do more Paulo Scott, too, and so many others…

The Punch: You have also translated from Spanish and French works. Whose works from these two languages do you particularly admire?

Daniel Hahn: I’m not nearly as well-read in these as I’d like to be. I’ve been reading quite a lot of children’s lit from France recently, which is a joy; and quite a lot of grown-up writing from Mexico, where every second person seems to be a brilliant novelist. But so much still for me to discover, I’m sure.

The Punch: Tell us about your association with languages. Did you always want to be a translator? What are some of the key areas a good translator must focus on before taking up a work to translate?

Daniel Hahn: I had no intention of being a translator — it happened entirely by accident. I happened to have some languages (passive Portuguese and Spanish because of my family background, schoolboy French) and I was asked as a favour to translate something and I said yes and here I am. In some ways I suspect the carelessness of that was useful — I don’t think I have many hang-ups about how difficult it all is and how stressed I should be about it, I’m not an anxious perfectionist, I translate quite quickly and quite casually, I think…

The Punch: You are a former chair of the Translators Association and the Society of Author and the national programme director of the British Centre for Literary Translation. You are also a part of English PEN, Pop Up and Modern Poetry in Translation. Tell us about your engagement in the activities to promote the art of translation, literacy and free expression?

Daniel Hahn: When I’m trying to explain the translation world to people I always draw the distinction between “translating” and “being a translator”, where “translating” is the obvious thing (reading a text and rewriting it as a different-but-identical text) and “being a translator” is everything else. Being a translator means being a part of the translation community, being part of the union, being an advocate for translation and literature and internationalism, it means teaching and mentoring new translators and supporting relevant institutions, it means talking about translation in public and writing about it in newspapers, being on grant-giving bodies or prize juries — in short, everything else that makes up the ecosystem in which translation flourishes. All these other things I do to make translation popular, to make translators visible, to make readers discover what we do, all that is, to my mind, a part of “being a translator” every bit as much as translating the books is.

The Punch: What are you currently working on?

Daniel Hahn: I have a lot of non-translating work to do — I do about a hundred public events every year, and writing, reviewing, judging prizes and the like; but I’ve got my next few translations lined up, too. (I usually schedule my book-sized jobs about a year in advance, so I know four or five books ahead of time.)

Still sitting in the pile waiting for me to translate them are: parts two and three of Phobos, a huge French YA sci-fi trilogy; a Belgian picture book; my third book by Guatemalan writer Eduardo Halfon (Duelo, co-translated with Lisa Dillman) and my sixth Agualusa, A Sociedade de SonhadoresInvoluntários; then there’s a Brazilian book which hasn’t been announced yet so I can’t tell you what it is…

The Punch: Who are some of the world’s other best translators you admire or look up to?

Daniel Hahn: I don’t know if I can answer this — at least half my favourite writers are translators and there are literally dozens of them. Though I suppose the ones for whom their greatness is most obvious to me are some of those working in the same languages as me, because they’re the ones whose work I read and think “But how the hell did s/he do that?” Margaret Jull Costa, Anne McLean, Alison Entrekin, Frank Wynne, Edith Grossman, etc. etc. They all do things that simply enchant and baffle me.

(An interview with José Eduardo Agualusa will be published in the next issue of The Punch)

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated