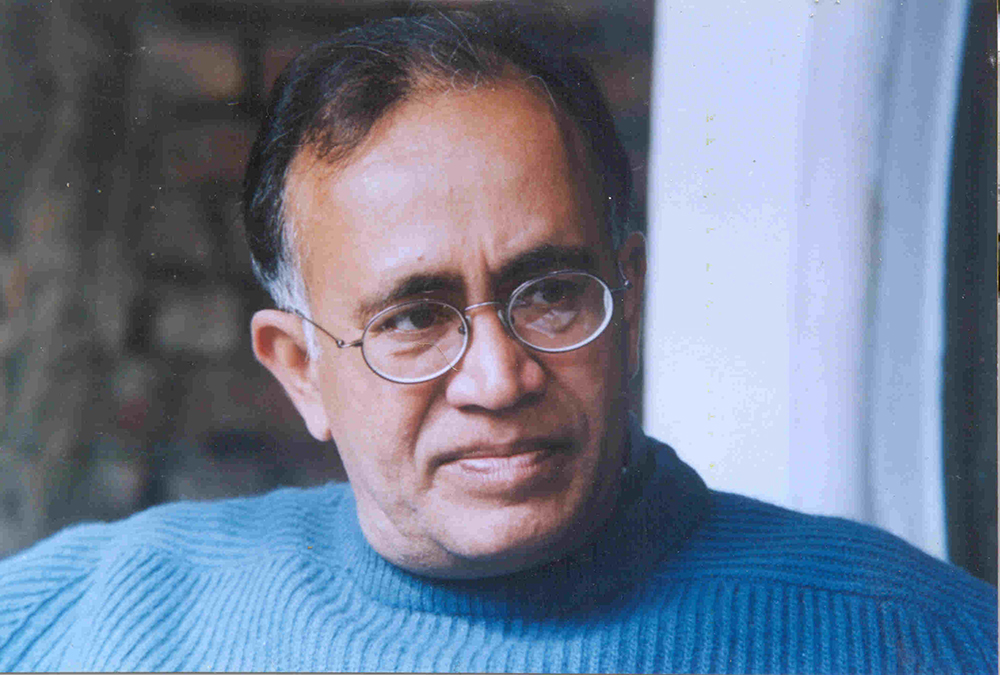

Irwin Allan Sealy. Photo courtesy Aleph Book Company

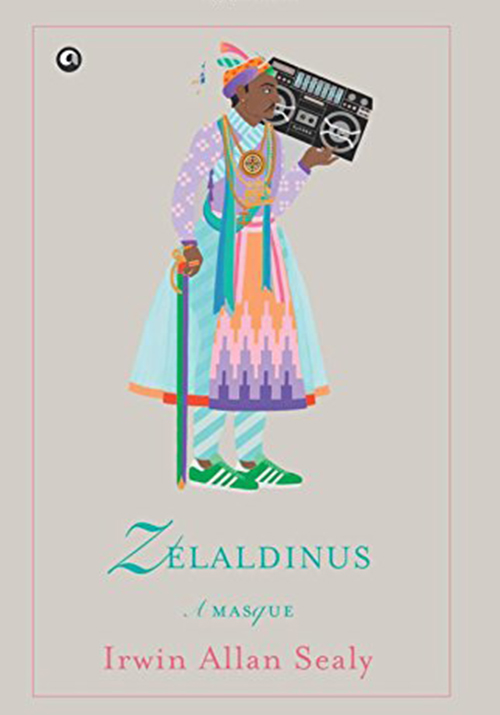

Irwin Allan Sealy’s new book, Zelaldinus: A Masque (Aleph Book Company) is a novel in verse which straddles the “porous” borders between poetry and prose. Set in Fatehpur Sikri (Agra), it retells the story of Jalal-ud-din (Zelaldinus) Akbar, the great Mughal emperor.

Talking about his discursive and exuberant narrative style, Sealy says, “We’re accustomed to imposing a false coherence on the phenomena of the world in the name of art. The classical approach is precisely that: you elide certain details and come up with a version that represents life according to a sedate consensus. I live and work outside that consensus.”

Excerpts from an interview:

THE PUNCH: All your books seem to be so much invested in the idea of a particular form, observing its rites, playing with its rules. Does this have to do with your preoccupation with form as a writer?

IRWIN ALLAN SEALY: Form could be just a preposterous pince-nez slung about my neck like an albatross, but I wear ordinary glasses too. The fact is you go to a new planet each time, with each new book and have to look with new eyes. The laws are different there, the gravity, the atmospheric pressure, the number of moons, and so on, and you must adapt. I like the idea of having to obey some rules while discarding others that may be only a kind of habit. We are creatures of habit and need to shake ourselves out of that stupor every so often. It’s not so much playing with new rules as responding to the eternal present with full and fresh concentration.

THE PUNCH: How did you settle on the form of Zelaldinus: A Masque? What was the trigger for the book?

IRWIN ALLAN SEALY: The trigger for the book was a visit I made to Fatehpur Sikri some ten years ago when I spent a few days on Akbar’s hill and came up with one or two poems. They were spontaneous effusions, nothing sustained, and with no narrative intent. The story that became Zelaldinus came later, and the masque form later still. Which disproves the notion that form is primary with me; it sets a template at some point and then you’re obliged to conform. The masque form had something to do with the pachisi board built into the terrace at the Diwan-i-khas where Akbar is said to have played a kind of human chess using women from his harem as pieces: what a pageant that must have been!

THE PUNCH: The sequence of poems in the book is divided into three sections named after the three seasons. How important was to let the narrative unfold through seasons?

IRWIN ALLAN SEALY: There’s a verse in Zelaldinus that reproduces the sequence of my seven actual visits:

summer summer summer summer

winter winter

now spring

If you want to call them movements, in the musical sense, then the story divides naturally into two parts: Irv’s first encounter with the ghost of the King one blazing hot afternoon in summer, and his midwinter return that sets up the story of cross-border love that affects the King as well as the lovers. It’s a shift of colour and mood too. And then there’s a final shift in tone in a kind of coda where the narrator returns to the hill one last time in spring. Because the poem was written over several years its evolution mirrors the seasons of its coming to be.

Zelaldinus: A Masque

By Irwin Allan Sealy

Aleph Book Company,

Rs 399, pp 155

THE PUNCH: While Zelaldinus tells the story of Fatehpur Sikri, it retells the story of Akbar. Tell us about your appreciation of the great Mughal emperor. Was it important for you to explore his character not just as an emperor but as a person, who helps a hapless lover, refused a visa to visit Pakistan, on a quest to meet his beloved across the border?

IRWIN ALLAN SEALY: On my appreciation of Akbar I’ll quote you an answer I gave in another interview so I don’t repeat myself:

Akbar’s military campaigns, his alliances, including matrimonial alliances, his evolving administrative system, all show a high level of achievement. He had what it took to create a great empire and govern it; he was a shrewd statesman, could manage defeated and rebellious kings, and knew how to cut his losses — the way he abandoned Sikri when it was no longer viable shows that. And then his personal qualities show him as a rare specimen among the kings of India. He was tolerant, interested in the intellectual and religious views of others, he was a fearless (some say reckless) hunter and yet a vegetarian, a man who appreciated music and painting and architecture; he was himself something of a composer and played the drum. Largely illiterate, he enjoyed being read to and listening in on debates, but he had also a practical bent and would turn his hand — the imperial hand — to various crafts and disciplines including stone-cutting and gunnery and hydraulics. He practised meditation suspended in a well, yet remained curious about life, loved nature and respected all creatures. He was an outstanding human being.

But I think we’ve heard enough from Akbar the King. Unless some new documents come to light historians can’t do much more than rearrange the furniture. I was never terribly interested in the plain facts of Mughal history. I wanted to know about the emperors as men, men like me. I have moments of tedium and enthusiasm and indifference and hunger and embarrassment and inspiration and greed and sloth and blankness, and so should the emperor of Hindustan.

THE PUNCH: How important was it to contrast the past with the present in the book?

IRWIN ALLAN SEALY: The past is only interesting when it intersects with the present, otherwise it can become a kind of escape. I didn’t want to do a historical. Zelaldinus opens a modern window on Akbar, into his head, as the man he may have been. It also tells a story from our own time that intersects with the past, where he and others from his time are part of the cast and instrumental in the plot.

THE PUNCH: Did you have the wide ambit of the masque’s themes “kingship, fatherhood, loyalty, love, valour and sacrifice” on your mind? Do you think they add to the narrative’s depth and dimension?

IRWIN ALLAN SEALY: You must tackle what moves you, not just subject matter. And as always the themes come last. The motives and matters you mention are flotsam all the time the book is being written; they become visible, as themes, only when you’re finished and done. Unquestionably, they add to the depth of the work, but you can’t sow them, so to speak. They just happen. It happened that my father died during the writing of this book; but there was already a poem I’d written about him as my Akbar. In the coda I include another poem about his passing, and the two poems, the living and the dead, communicate with one another and resonate.

Page

Donate Now

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated