I woke up today to two things: the memory of my father, and Reshma’s haunting ‘vey main chori chori’. Each in itself is not unusual. Since my father passed away seventeen years ago, there are days when I wake up with a very visceral sense of having spent time in his company. Some lucky days, I even recall the scene with lucidity. And what I have learnt is that awake I find it difficult to conjure him in entirety; his smile, his turban, his walk, fragments of his conversation — these are what come to me. But in sleep’s realm, my unconscious not only conjures him up, but also throws me in animated conversation with him.

Coming back, the juxtaposition of Reshma’s song and my father intrigued me. I listened to the song on YouTube as I brewed my morning cuppa. Reshma’s rendition of this song is my favourite; she brings to it an earthy pining for what exists but might not be hers, rooted in all those mythic Punjabi folk tales of unrequited love. And then, as the tea leaves scented with fennel wafted, Reshma in the background, my mind plucked this phrase out of the air:

pyaar pichhe har koi mitiyaan vi chhaan da …

In the pursuit of love, I sift sand even.

And I knew why my mind had put those two disparate elements together. Mitiyaan vi chhaan da. A ubiquitous Punjabi phrase, and yet poignant. In the pursuit of love, because of love, for the sake of love, I sift sand even. All those lamentations of unrequited love of Majnu, Farhad, Punnu are alluded to in this phrase. But its ubiquity lies in the manner in which it gets used in casual conversation when a person, while referring to the apparent hopelessness of a task, will say, it is the equivalent of mitti chhanana, of sifting sand.

And I recalled conversations where my father had used this phrase, to express the apparent futility of an endeavour and yet, one which was nevertheless worth pursuing. My own similar stubborn attempts then have an arc that leads back to him. I have recently started work on a novel, an ambitious novel, a novel which (attempts to) tussle with themes of identity and home and the illusion of choice, and, expectedly, I am flailing. Writing the first draft is a feverish exercise, an attempt to coax the nebulous into some shape, to pluck thoughts from the ether of mind to words on screen — an endeavor that reminds me daily that the attempt to create something out of nothing has all the fatigue of a marathon run without the glory of even an exultant selfie at the end.

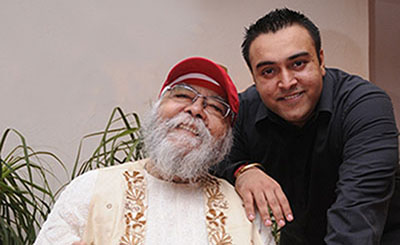

No surprise then that I have been thinking of my father. I started to write because of him.

Writing snuck upon me in the guise of a tai tai, a Chinese colloquial term for a woman of leisure. Perched atop a Singapore high-rise, at the turn of the millennium, I was to take a sabbatical from the life of a corporate road warrior and indulge in some ‘me’ time. And do what expat wives did when their spouses relocated overseas: languorous coffee mornings, salon sessions with girlfriends, retail therapy. I was on my way to realising this barmy prospect in sunny Singapore when the plains of Punjab collided with me. Rather, its fields. That grew mustard and wheat and rice and, for a period in the eighties, militants. Which made my little town on the Indo-Pak border a militant hotbed. And images started to swim up, of a time that I had left behind, or so I thought ...

Late-night ringing of the doorbell, my lawyer father hurriedly summoned, then disappearing to return at dawn, his face drawn with what even my childish self could fathom was more than just fatigue. Newspapers with redacted text. Black tea served with leftover cream because the milkman’s delivery was interrupted, again, by curfew. Frequent abrupt school closures. Despite which my vocabulary grew: TADA, separatists, communal…

It was the eighties, Khalistan movement was at its peak, Punjab Pulce — as the police is routinely, and with some deprecation, called — was hunting down Sikh militants and notching up its tally of arrests, and men like my father — criminal lawyer by profession, Sikh by faith, Punjabi by nature/upbringing/birth? — got accustomed to being roused by bewildered parents whose sons had been whisked away from homes in the night.

Those strapping Sardars, whose forefathers had changed the course of mighty rivers to transform a scrubland into the fertile Punjab of today, who had fought the marauding hordes of Nadir Shah and Abdali, whose toil fed an entire nation, were left hapless in the face of this new adversity: Encounter deaths.

Page

Donate Now

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated

.jpg)