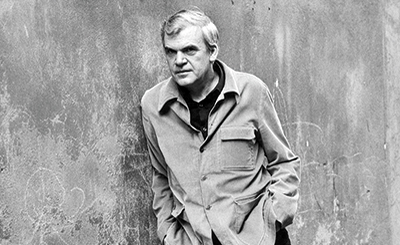

Kashmiri author and poet Shabir Ahmad Mir. Photo courtesy of the author

In his debut novel, The Plague Upon Us (Hachette, 2020), Kashmiri writer and poet Shabir Ahmad Mir tells the story of love and loss, friendship and betrayal, laced with the horrors of the war that has forever raged in Kashmir. Mir, who comes from Gudoora in Pulwama, presents truth as an antidote to the injustice of the times. “‘In times like these, truth is perhaps the only justice we can have, the only vengeance we can wreak,” he writes. It is truth, in addition to the horrors of the past inflicted on him and his friends, that the protagonist, a young man named Oubaid must confront to come to terms with the mind-numbing violence that keeps ripping through the streets of his homeland. When he does that, there emerge “four echoes of a story, narrated by four childhood friends — a youth caught in conflict, the daughter of a social climber, the son of a moneyed landlord and a militant.” As their tales intersect, they unravel a truth “that is not always the sum of its parts — one that reveals the full tragedy of a people buffeted by circumstance and desperately seeking salvation.”

In this interview, Mir says that the novel was “borne out of the frustration due to the failure to reconcile the witness of my memories with our history that is peddled in its various narratives.” Kashmiris, he says, a people who lost their way at the crossroads of history. “We have been made to take so many turns, so many byroads that we have created a labyrinth of our own,” he says. Excerpts from the interview:

The brightest stars shine in darkest of skies. In the time of internet blackout and abrogation of Article 370, you’ve written a dazzling work of fiction. What inspired you to write during this time?

I don’t know if inspiration is what we can call it. This novel was borne out of the frustration due to the failure to reconcile the witness of my memories with our history that is peddled in its various narratives. The lockdown just triggered the fission of that accumulated frustration.

Kashmir’s story is so complex. Do you think your novel reinforces this point or does it clear a path to the heart of the matter?

I am very glad that you asked this question because most of the people who have read the novel seem to miss this point. The heart of the matter of Kashmir is very clear but the path to that is not. To quote from the novel, “We are a people who lost our way at the crossroads of history... We have been made to take so many turns, so many byroads that we have created a labyrinth of our own.” And it has been my attempt to project this labyrinth of narratives and perspectives that our history and politics and struggle have been reduced to not the struggle itself.

Reading your novel felt like a cross between a Shakespearean tragedy and epic Arabian storytelling. Did you draw on them?

Our (Kashmiri) oral story tradition is heavily influenced (and heavily borrows) from Arabic and Persian epics as well as their style of storytelling. So, obviously, that influence is carried on in this novel. But more importantly the novel also carries the deliberate imitation of Arabian Nights, both in the mode of narration as well as, to some extent, the criss-crossing of stories. This is made explicit even by the names of the chapters: “One Thousand Minutes And One”, “First Tale”, “Second Tale,” etc. This is because if there ever was a Kafkaesque version of Arabian Nights, it will be Kashmir. About other influences, I believe there is something of everything that I have ever read and that might even include Shakespeare. Although, consciously, the novel leans more on Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex.

What’s your take on “own voice” debate in literature? For example, what do you think of non-Kashmiri authors telling a story about Kashmiris?

I don’t believe in this “own voice” stuff. It makes art so parochial, so limited. I believe in a story. Whether it is by an “own” writer or the one from outside doesn’t matter to me. Yes, the locals, the insiders should tell their story. They ought to bring their own voice, own experience, own perspective to the table and there are certain things that they would be able to do that no outsider ever can but that doesn’t and that should not mean that the insiders have a monopoly over anything. Let anyone who can tell the story tell it. That is it.

The “king” in the end is not satisfied with just one story and has a harem of “a thousand rooms and one.” Do you think there are lots of potential stories waiting to be told? How’s the literature scene in Kashmir and how difficult it is for someone to get published by mainstream publishing houses?

As I said earlier, Kashmir is the Kafkaesque version of Arabian Nights. So many stories of horror and pain to be told! The only problem is, as Arundhati Roy puts it, “There is too much blood for good literature.” The Kashmiri literature scene right now is all about how to navigate through this conundrum of too-much-blood-for-good-literature. On one hand you don’t want to betray your own people — their struggle and their tragedy — but, on the other hand, you don’t want your fiction to be reduced to a mere polemic. The thing is our stories of misery are too true to be believable. And how to tell such a story to an audience outside Kashmir remains our challenge. And I believe there are people out here who are slowly but steadily rising to this challenge.

The Plague Upon Us, By Shabir Ahmad Mir, Hachette India, pp. 240, Rs 550

By recounting almost the same events from multiple perspectives, are you meaning to tell the reader that there are many vantage points to look at the same event?

It is not just about an event and its vantage point(s). It is also about the evaluation of the event, of the character. See, a minor theme of my novel is the phenomenon of collaboration. Collaboration and collaborators are sore spots of Kashmiri political landscape. But the collaboration is not a monolithic entity which could be explained away by a neat political theory or historical narrative. One man’s choice is another man’s inevitability. By bringing in more than one perspective on the same phenomenon, on the same event and even on the same character, I try to challenge the reader’s evaluation of what he has assumed to be his infallible understanding of the event/character.

I have “Mir” in my name and people mistake me for a Kashmiri. They keep asking me to suggest books on Kashmir or by Kashmiri writers. I can suggest only a few that I have read. Would you please suggest some books, both fiction and non-fiction?

The curse of being a (Kash)MIRi, I guess. When you say Kashmiri writers, I assume you are referring to Kashmiri writers writing in English. Otherwise, this question could lead to a very, very long answer. My suggestion for someone who has not read Kashmiri writers yet would be to start with the trinity who started it all: Agha Shahid Ali in poetry, Basharat Peer (The Curfewed Nights) in non-fiction and Mirza Waheed (The Collaborator) in fiction. As far as recent works are concerned, I would suggest Firoz Rather’s collection of short stories, The Night of the Broken Glass, Huzaifa Pandit’s debut collection of poems, Green is the Colour of Memory, and the anthology of ethnographic essays by Kashmiri writers titled, A Desolation Called Peace: Voices from Kashmir, edited by Ather Zia and Javaid Iqbal Bhat. But if someone wants to engage with Kashmiri literature written in English on a more sustained way and in a more incisive way, I would suggest he/she should start reading local online journals, like Wande Magazine, Kashmir Lit and Mountain Ink. They have been publishing some really wonderful literature — experimental, sometimes even immature, but very close to the ground and the reality of everyday Kashmir. If you want to read some great Kashmiri writing in English (and not on Kashmir), then Siddhartha Gigoo’s recent work is also something to be looked out for.

What are you currently reading? Could you name some books that you’ve enjoyed reading recently?

I just finished Homeland Elegies by Ayad Akhtar. It’s an immensely invigorating and thoughtful novel, that is if one can strictly call it a novel. Some of it stayed with me quite forcefully which is a rare thing for me.

Currently, I am reading The Innocence of Memories by Orhan Pamuk. I didn’t know this book even existed. It is a fascinating book. It comprises some absolutely stunning photographs, along with the screenplay of the documentary of the same name, The Innocence of Memories, by Grant Gee which, in turn, is based on Pamuk’s celebrated novel and the Museum he established in Turkey — The Museum of Innocence. It also contains a conversation between the filmmaker and Pamuk. It makes one revisit Pamuk’s novels, particularly The Museum of Innocence.

A hypothetical question. What’s more difficult to survive — an internet blackout or a physical lockdown?

I haven’t survived either of them yet. The internet is yet to be completely restored here and we have been living in a state of siege for decades now. Besides, it is just a matter of time before internet is snapped on one pretext or another or another round of curfews is announced. But, yes, I would like to answer your hypothetical question hypothetically. When it comes to a matter of survival, all that matters is the survival itself. It doesn't matter whether it is internet blackout you survive or a physical lockdown.

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated