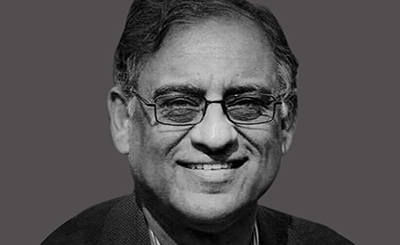

Ajit Baral at the Nepal Literature Festival. Photo courtesy of the DSC Prize for South Asian Literature

Festival Director of Nepal Literature Festival says the country is uniquely placed to be a neutral South Asian space for conducting meaningful dialogue to promote plurality, foster tolerance and generate empathy for all of South Asia

At the Nepal Literature Festival, held in the backdrop of the scenic Fewa Lake at Pokhara in Nepal in December, the DSC Prize for South Asian Literature gave away the prize to the winner, Amitabha Bagchi, for his fourth novel, Half the Night is Gone (Juggernaut Books, 2018).

After its inception in Kathmandu in 2011, the Nepal litfest moved to Pokhara in 2016. This year, there were three different platforms for the various sessions, spread over four days. The venue was surrounded by the mighty Himalayan range on the one side and the lake on the other. Book lovers, authors and literary enthusiasts thronged the festival to breathe in the literary air.

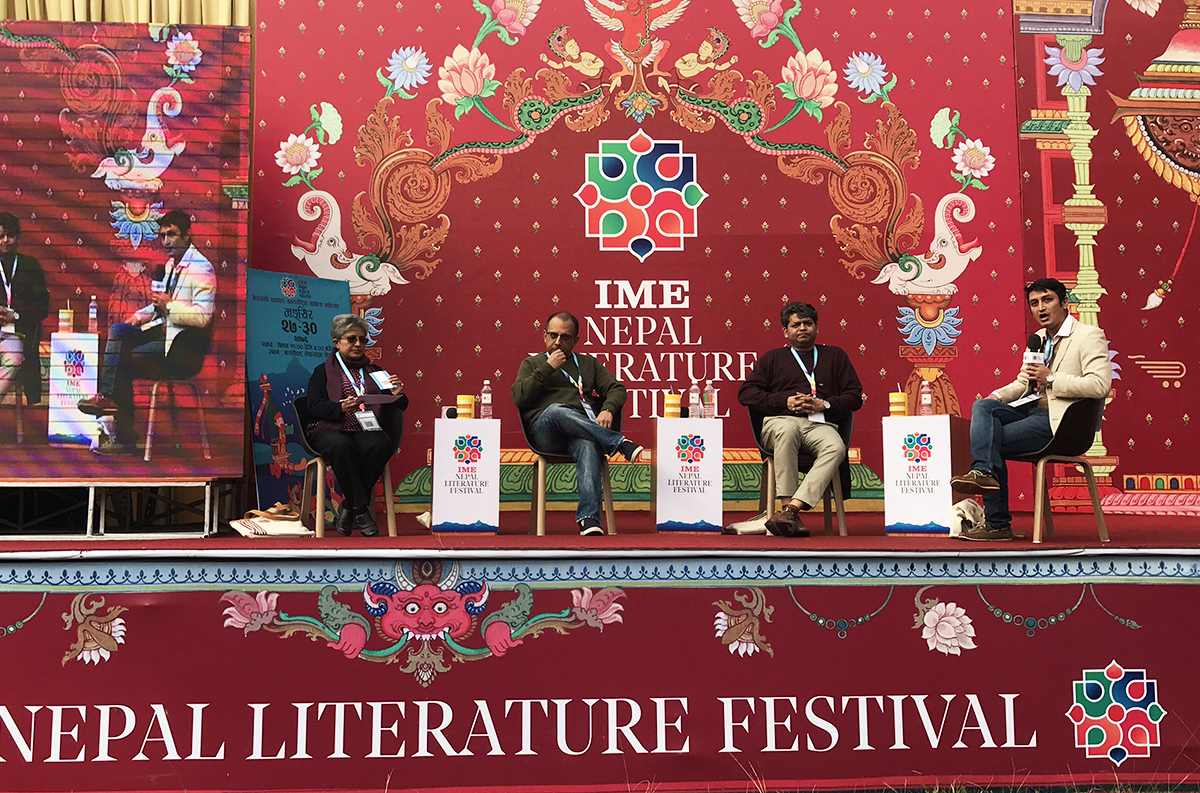

Among the six shortlisted authors, four were present at the festival. — Amitabha Bagchi, Jamil Jan Kochai, Raj Kamal Jha and Manoranjan Byapari, along with translator Arunava Sinha. The two other authors, Madhuri Vijay and Sadia Abbas, couldn’t make it to the fest. The jury, chaired by Harish Trivedi, and the shortlisted authors had some interesting sessions at the festival.

Festival Director Ajit Baral and producer Niraj Bahri, with the help of their extremely enthusiastic team, put up a wonderful show that celebrated the exuberance of literary traditions.

In this interview, Ajit Baral, author of, among other books, Lazy Conman and Other stories (2009), says that Nepal is uniquely positioned in South Asia as one of the most liberal countries in South Asia where one can discuss “anything under the sun”. He says: “Our festival is uniquely placed to be a neutral South Asian space for conducting meaningful dialogue on a host of issues to promote plurality, foster tolerance and generate empathy for all of South Asia’s denizens. The rest of the South Asian countries, on the other hand, cannot aspire to be such a forum, because some have clamped down on freedom of expression, some are suffering from the rising spectre of intolerance and religious fundamentalism, and some are at loggerheads with other countries in the region,” he says.

Excerpts from the interview:

Shireen Quadri: Tell us about the inception and the nine-year-long journey of the Nepal Literature Festival (NPF)?

Ajit Baral: Every city worthy of its name has, at least, one important cultural event. For example, Locarno and Cannes have a Film Festival; Frankfurt and London, a Book Fair; Jaipur and New York, a literature festival; Venice and Toyko, an art festival. So, why not Kathmandu? We asked ourselves. And that’s how the idea of having a literary festival of our own was born. But we didn’t really know then what a huge undertaking it is to organise a literary festival. That was a blessing in disguise, because had we known it, we wouldn’t have started the Nepal litfest in the first place.

The first edition of the festival was held in 2011, in a small hall of a restaurant in Kathmandu, which accommodates just around 150 people. But the Festival was well received. The turnout was far higher than we had hoped for — so much so that the audience spilled over from the festival hall to the adjoining lawn to listen, over loudspeakers, to the proceedings transpiring in the hall. The coverage in the media was overwhelming.

Encouraged by the success of the first edition, we decided to host the event at the bigger premises of the Nepal Academy the year after. That venue served us well for four years. But, after a gap of one year, because of the mega earthquake and the Indian blockade, which made it impossible for us to hold the festival, we moved the festival to the more scenic city of Pokhara. Participating writers liked the festival venue with Fewa Lake as backdrop and the snow-clad mountains peeking at you from a distance so much that we decided to hold the festival permanently in Pokhara. In the last nine years, the festival has grown into probably the most important event — literary or otherwise — in the country. And it has spun off many smaller litfests in the nook and crannies of Nepal.

Shireen Quadri: How do you program the festival? What are the most important aspects of the festival?

Ajit Baral: A small group of people, who are passionate about the written word and interested in intellectual pursuits, are behind the Festival. This group meets regularly to discuss the kinds of topics and speakers that we should give space to at the lit fest. It also seeks suggestions from friends and well-wishers regarding possible topics and speakers. In short, it cast its net wide in order to make the discussion topics as inclusive and pluralistic and relevant as it can.

The Nepal Literature Festival was conceived as a forum for fostering pluralities of thoughts and ideas, tolerance, inclusiveness and literature. True to its founding ethos, it has over the years given space to diverse — often competing — ideas and unheard voices. It has also been a platform for engaging with issues pertinent to the times. For example, we have had a discussion on populism, a global scourge that we Nepalis been infected with of late; on the tabling of the recent citizenship bill that discriminates against women; our experiment with federalism which is fraught with risks. I think these are the most important aspects of our Festival.

Fewa Lake at Pokhara in Nepal at night. Photo: Wikipedia

Shireen Quadri: How would you describe the Nepal Literature Festival to the book lovers in India and the Indian subcontinent?

Ajit Baral: The Nepal Literature Festival is not as big as some of the literary festivals in South Asia, but it is growing every year. And though most of the discussions happen in the Nepali language, we hope to change that and have more conversations in English in line with our aspiration to turn it into a democratic, South Asian forum for writers and public intellectuals from the region. Given that Nepal is one of the most liberal countries in South Asia where one can discuss anything under the sun, our festival is uniquely placed to be a neutral South Asian space for conducting meaningful dialogue on a host of issues to promote plurality, foster tolerance and generate empathy for all of South Asia’s denizens. The rest of the South Asian countries, on the other hand, cannot aspire to be such a forum, because some have clamped down on freedom of expression, some are suffering from the rising spectre of intolerance and religious fundamentalism, and some are at loggerheads with other countries in the region.

Shireen Quadri: The publishing industry in Nepal is at a very nascent stage. How would you see it growing?

Ajit Baral: Actually, it is not. The publishing industry in Nepal may have been in a very nascent stage a decade ago, but it has grown in leaps and bounds over the last few years, thanks to the rising literacy rate and population, the boom of the media, which is giving increasingly greater space to books, the coming up of litfests like ours, etc. Until a decade ago, it was unthinkable for publishers to print more than a thousand copies initially, but now publishers regularly print books in the thousands. The quality of printing, cover design and layout has gone up considerably. Shashi Tharoor had, in fact, said, when he was in Kathmandu for the lit fest in 2014, that the quality of Nepali books was much better than Indian vernacular language books.

Having said that, the English language publishing in Nepal is not the same. There are only a handful of writers writing in English and they preferred to be published in India, even though Indian publishers don’t promote them at all and ninety percent of their books are sold in Nepal. So, little publishing is happening in Nepal in English. It’s time we took initiatives to make English language publishing as vibrant as Nepali language publishing.

Shireen Quadri: It would be wonderful to see some literary talent come up and get recognised and as Surina Narula, founder of the DSC Prize for South Asian Literature, mentioned during the DSC award ceremony in Pokhara that books from Nepal should make to the longlist and beyond. What would you like to add to this?

Ajit Baral: Yes, it would be wonderful to see Nepali talent bursting onto the international literary scene. But for that to happen we need to have a largish community of writers writing in English and a very vibrant translation scene. I don’t see the former happening anytime soon. As for the latter, we have seen a spike in interest in translation, both from English to Nepali and vice-versa. On top of that, Indian publishers are looking for translators and good works of Nepali literature to translate into English. Sadly, we don’t have many translators translating from Nepali to English, except Manjushree Thapa, Prawin Adhikari and maybe a handful of others. So, it will be safe to say that it will take at least a few more years, if not a decade, for a brilliant Nepali writer to catch the attention of South Asia or the world.

Shireen Quadri: Do you plan to invite more writers from India and the Indian Subcontinent in the near future?

Ajit Baral: Since the inception of the festival, we have been inviting authors from India and other South Asian countries, albeit in smaller numbers. The late Vinod Mehta, Ramachandra Guha, Shobhaa De, Uday Prakash, Annie Zaidi, Amish Tripathi, Barkha Dutt, Mohammed Hanif, Farah Ghuznavi, Namgay Zam, etc., have attended the previous editions of the festival. But we hope to expand the list of international writers in the subsequent editions of the festival. In fact, we have to, if we are to grow it into a truly South Asian Festival in spirit and tenor.

Shireen Quadri: What are some of your most memorable literary festival’s moments in the last few years?

Ajit Baral: As an organiser of a lit fest that is going on since 2011, we have been privy to many fond moments — moments that have brought a chuckle in our faces, joys in stress-filled times and succor in despair. Among these moments are: Ramachandra Guha holding forth on his book Democrats and Dissenters (2016) with writer Kanak Mani Dixit in a light drizzle holding umbrellas; Hindi writer Uday Prakash thanking us for inviting his wife to the festival, which was something none of the festival had done before; Pakistani writer Mohammed Hanif complimenting us for our choice of the venue by the bank of Fewa Lake; seeing brilliant but little heard voices that we had introduced through the festival going on to become household names in the country; people heaving praise for organising the “Mahakumbha” of words.

Shireen Quadri: Who are the most prominent literary authors in Nepal?

Ajit Baral: Laxmi Prasad Devkota, BP Koirala, Parijat, Bhupi Sherchan, Shanker Lamichhane — these are some of the most prominent authors of yore. Though dead for long, they are are still being read and their influence on the younger generation of writers and readers is still firm. Among the writers writing today, I would name Khagendra Sangraula, Buddhisagar, Nayan Raj Pandey, Amar Nyaupane, Narayan Wagle, Kumar Nagarkoti, Sarita Tiwari, etc, as being the most prominent, but people may have issues with the inclusion or exclusion of some.

Panels in progress at the Nepal Literature Festival. Photos: DSC Prize for South Asian Literature

Shireen Quadri: Being an author and publisher yourself, where do you draw your literary inspirations from? Who are your favourite authors/books?

Ajit Baral: There are so many new things left to do in Nepal that the very idea of breaking into an uncharted territory of, let’s say, young adults books, or being the leader in Nepali publishing by just putting a premium on editing or experimenting on cover designs gives me a kick. The sweet thought of doing what no one else is doing, like the litfest, and being ahead of the pack, like we are in the publishing industry, is what keeps me doing what I am doing.

I have had so many favourites, but they have changed over times. For example, I used to like Salman Rushdie a lot, but I cannot read him any longer (post The Ground Beneath Her Feet). Ditto Ben Okri. I think I am no longer besotted with magic realism. I have read most of JM Coetzee’s books and continue to love him (Disgrace is my favourite). Rohinton Mistry is one of my perennial favorites (I always keep A Fine Balance on my list of five best books), but he takes ages to complete a novel. I like Pankaj Mishra a lot, for the breath of his knowledge (His travelogue Butter Chicken in Ludhiana is delightful); VS Naipaul, for his language — so beautiful, so deceptively simple; Arundhati Roy, for her rhetorical flourish; Uday Prakash, for his stories that pulsate with humanity.

Shireen Quadri: What is the line-up for the 2020 edition?

Ajit Baral: It is too early for us to talk about the line-up for the 2020 edition of the festival. We usually start planning for the next edition five or six months before the festival dates. However, some of the big, award-winning writers — including a Nobel prize-winner and International Booker Prize-winner — have already shown interest in attending the next edition of the festival. So, we hope that there will be much to look forward to in the new edition of the festival.

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated