Avni Doshi, the author of Burnt Sugar, which has been longlisted for Booker Prize: Photos: Sharon Haridas

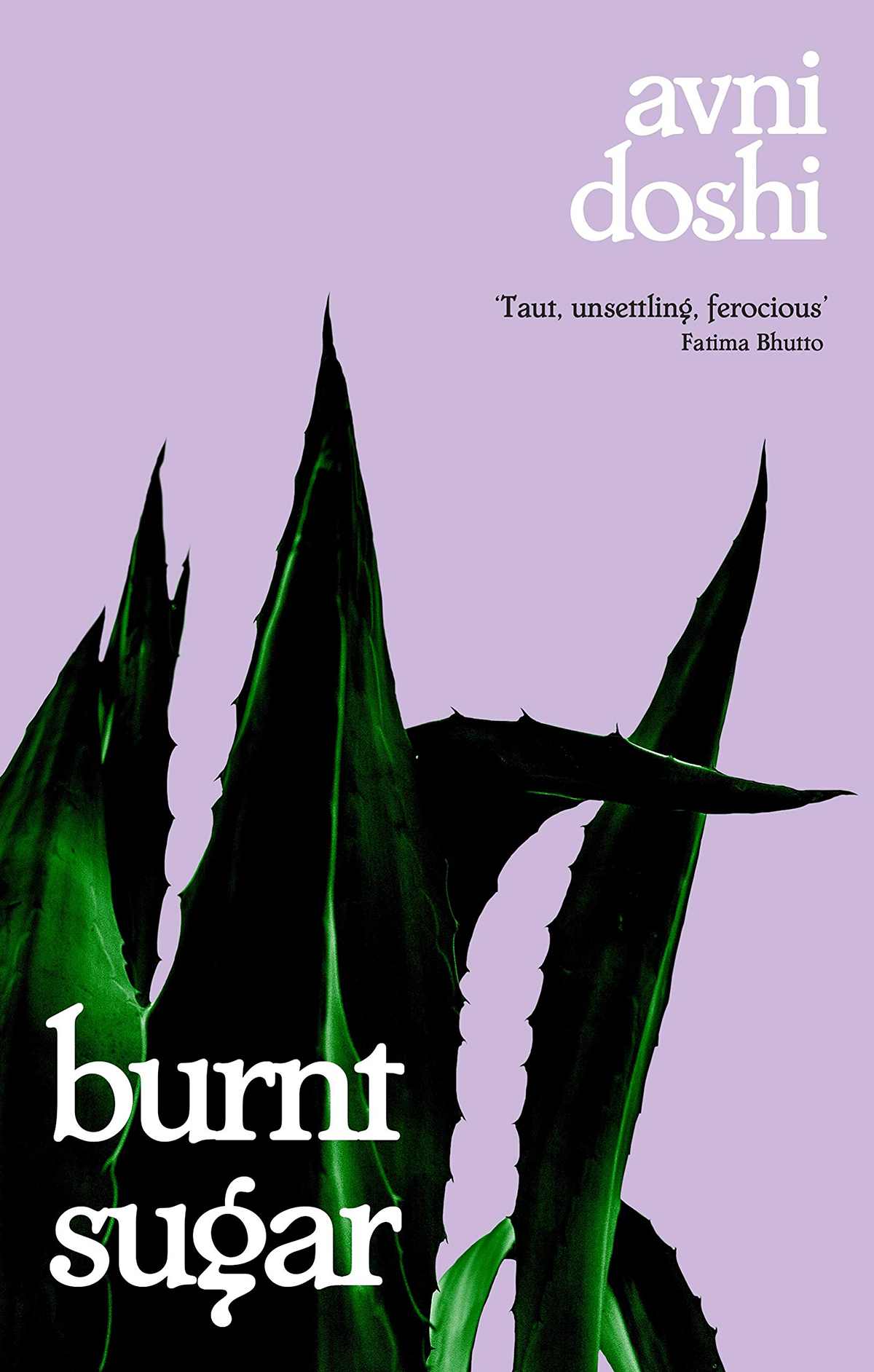

Avni Doshi, the 37-year-old Dubai-based author of Burnt Sugar (Hamish Hamilton, 2020), her debut novel which has been longlisted for the Booker Prize, on the interconnectedness between motherhood and madness, why she finds writing in the first person fascinating, getting lost in the writing process and how the realisation that memory could be rewritten and imbibed has shaped her reading of literature.

Donate Now

Shireen Quadri: Your first novel, Burnt Sugar, published in India as Girl in White Cotton (Fourth Estate, 2019), is among the eight debut novels longlisted for this year’s Booker Prize. First novels are special for many reasons. Mostly, for the simple fact that it lets a writer find a voice, as it were. But first novels are also, quite often if not always, hard to write. How did this novel happen to you? You wrote once that the trigger was a single image of a mother and daughter sitting before a window, which had sprung to your mind after you had found yourself staring at a picture of yourself, half in shadow and half in light, with your face somehow reflecting two women. How did the novel progress from that image?

Avni Doshi: I began to write through what I saw and felt in that image almost immediately. There was already a narrative stitched into it. That initial text was a small fragment, but it was the seed for two characters, a mother and a daughter. The rest of the writing moved forward from that space. I felt that the characters were revealing things to me, rather than me writing or inventing who they were. I began to see that they had been living somewhere in my mind, unacknowledged, for a long time, fully formed as they were, with a cogent history and perspectives that emerged.

The novel was hard to write, but my understanding is that this is not unique or remarkable in anyway. Writing is difficult, it’s easy to get lost in the process of writing a novel. I had to find my way back many times.

Shireen Quadri: At the heart of your poignant novel is the deeply fractured and dysfunctional relationship of the mother and daughter, Tara and Antara, with the mother sliding into dementia and the daughter coping with the task of playing a caregiver as well as a memory-keeper. Did you conceive this novel as a meditation on madness and motherhood? How did you go about weaving the intricate web of their fragile relationship?

Avni Doshi: It was always my observation that motherhood and madness were interconnected somehow. I could discern it in the intensity of feeling I saw in the mothers around me. And the same was true of how desperately I wanted to be mothered, in how I still desire that particular ferocity of affection. Maternal love always seemed to me to be a wave — completely overpowering, formed by biology and culture — and like water on a stone, it was the thing that would shape you. Recently, after having my own children, I can see the clawing, the craving in the relationship.

I never saw the relationship between Antara and Tara as fragile. To me it’s unbreakable, even when it looks broken — even if there is estrangement, pain, death, there is no break from the mother. I think sometimes of a famous sculpture by Louise Bourgeois as the perfect expression of motherhood. She made an enormous spider, titled Maman. You can walk around it, weaving through its spindly legs. You can stand underneath it, even lie down and take in the expanse of its body. It’s quiet, constant, looming and protecting all at once. It’s a shelter, but it blots out the sun. When I began to write, I knew this would be the case — even if mother and daughter attempt to destroy each other, there is no escape. One is forever in the reflection of the other.

Shireen Quadri: There have been many novels centering around fathers and sons, but perhaps not too many around mothers and daughters. While researching for this novel, did you look out for works that explored the relationship between mothers and daughters or just those that delved into motherhood, particularly in fiction?

Avni Doshi: I began writing this novel seven years before it was published, and at that time my diet of literature was quite narrow and meagre. I wasn’t really looking at mother-daughter relationships in fiction. Later, however, I read various books, mostly memoirs, that looked at this relationship. Notably, the work of Rachel Cusk and Nadja Spiegelman were extremely influential. I didn’t know how honest and unafraid I could be until I came across their words. I felt I had received permission to be radically transgressive.

Shireen Quadri: Reza Pine, the photographer-artist, is a character drawn with a lot of care. At some point, Antara mentions that he was difficult to sketch because he always spoke in terms of fluid reality. The truth, for him, was subjective and experience continuously altered itself as memory. How did you go about lending flesh and blood to such a character, at once mystical and mystifying, and inscrutable, like desire itself?

Avni Doshi: I suppose the answer is in your question — I formed Reza Pine in the shape of Antara’s desire. The idea for this character came rushing into the gaping void between mother and daughter. And this is probably the way the entire book emerged. Writing in the first person is fascinating because the insistence of the narrator abounds.

Shireen Quadri: Though it foregrounds memory and forgetting, the novel also manages to explore a wide gamut of ideas — love and betrayal, art and artifice, pretense and uprightness, submission and rebellion, truths and lies, motherhood and what it takes to be undone by your own mother. You also bring in an undercurrent of socio-political element — from Babri Mosque demolition to the riots that flared up in Bombay, and, later, to the falling of the twin towers in America. How did all this come to cohere?

Avni Doshi: The images of the Babri Masjid, the history of that place, have been in my mind since I was first told about it. I can’t pinpoint when this was, but I was haunted by the layering, or what I saw as a confluence, of bloodshed and devotion. I remember looking to artists like Rummana Hussain and Nalini Malani, and realizing that images and stories could offer a way to think and feel around this.

The way the structure of the novel came together is ultimately mysterious to me. I tried along the way to plan and plot, but the story felt dead that way, and in the end, I had to write slowly, making decisions about the narrative only when I arrived at a point. Sometimes I would reach a kind of dead end and throw pages away. Starting at the beginning of each draft felt at once daunting and full of opportunity.

Shireen Quadri: Memory, however, remains the key throughout the novel. It has been your primary preoccupation as an art historian. You have spoken about having read a lot of MaÌrquez when you were younger, and later, as a curator, putting together shows that hinged on the way memory and amnesia functions in his writing. In the novel, you seem to keep your focus on how family memories are constructed and reconstructed. What do you find fascinating about memory as a writer and as someone who has studied art? Are there other artists and writers who have helped shape your ideas?

Avni Doshi: I recently was speaking to an artist, and she explained the lure of memory perfectly. She said that the time it takes to perceive what is in front of us, for the brain to form a picture of what the eye sees requires an infinitesimal passage of time, and, therefore, our experience of the present is always past. And that the present can never truly be known to us. In other words, the past is the human condition, the human experience. We make sense of the world in retrospect. The idea of living in the present, of being present, which is a kind motto to commodify wellbeing, feels as trite as a hallmark card to me.

Derrida’s writing about the archive, and the curator Okwui Enwezor’s exhibitions around the subject were the first to really convey how public and private memory is constructed and refined. I never really considered that memory could be rewritten and imbibed. It was a major turning point in my thinking, and shaped my reading of literature.

Shireen Quadri: Is it easier to set the novel in a city you are familiar with? Did you think of Pune as the setting when you got the flash of the story? Did the ashram made it vital to the narrative?

Avni Doshi: In earlier drafts, the city was unnamed, and the majority of the story took place within the walls of the ashram. While I was writing those drafts, the specificity of the city didn’t feel necessary to the story. It was only later that Poona/Pune became a character in the novel, drawing on and distorting Antara’s perspective and her memories as much as her mother does.

Shireen Quadri: While reading the novel, I kept thinking of the inside-outside perspective, contradictory, just like the human relationships. There are people in the family and outside the family. For instance, there is Antara’s mother and then there is Kali mata. There is her father, who is both a member of the family and yet quite removed from their current reality. There is the society on the one hand and ashram, its antithesis, on the other. The mundane minutiae of the mother-daughter, the constant construction and reconstruction of the family memory, unfold largely within the four walls, but then there is also the club, where, you have spoken about elsewhere, “the history isn’t acknowledged, but is unconsciously re-enacted every day.” How conscious were of you of the spaces the story was taking place in when you were working on the novel?

Avni Doshi: The spaces the characters move through are central to the story, but I didn’t consider how they would operate as signs of an insider-outsider experience. In a sense, all spaces offer that possibility — what creates this tension is the person who experiences the space. In other words, character and the narrative perspective are really what drive the sense of alienation in the setting, as well as in the language choice. It became clear as I was writing that this was the lens through which Antara sees the world, embedded as she is in her own experience.

Shireen Quadri: Burnt Sugar is suffused with simple, delicate, unencumbered sentences, as if they were imbued in the feathery lightness of cotton. Do you see your practice as an artist informing your craft as a writer?

Avni Doshi: I don’t have a practice as an artist. I studied art history, which is quite different, and even though I have often fantasized about being an artist, I could never call myself one. My process when writing art historical texts was always separate to how I approached writing the novel. With art criticism and essays, I spent a good deal of time researching, looking at an art object, considering the experience of viewing a work — and writing the novel was a process of going inward, waiting and watching to see what would arise internally.

Shireen Quadri: We began with how you began the novel with an image. There are many other powerful images throughout Burnt Sugar. Early in the novel, Antara talks about writing stories from her mother’s past on little scraps of paper and tucking them into corners around her flat. The novel ends with another powerful image. Antara stands at the door of the flat, listening to the voices of both sides of her family inside the house, whom she had left singing and having fun, along with her infant daughter Anikka. She rings the bell and leans against the wall, “waiting to be let back in”. This image is pregnant with meaning, bringing into play, once again, the inside-outside underpinnings. How did you come to this end?

Avni Doshi: The end is actually slightly different in the Indian version of the book and in the international edition, where I extended the text a few pages, but the sense of being an outsider, of looking in with ambivalence, of moving between longing and repulsion, is the same. The end was not something I planned in advance, but once I arrived to that point, I realized that was where the book would have to end. It is a scene that begins as relatively normal, but slowly spins off its own axis. I am interested in that interplay between the real and the surreal, and how a surrealist quality in the language and the text can describe the visceral experience of a moment.

Comments

*Comments will be moderated