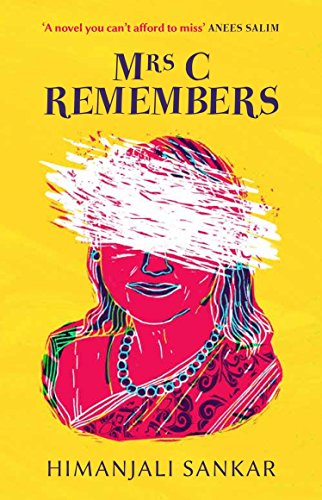

Himanjali Sankar. Photo courtesy of the author

Himanjali Sankar on her first novel for adults, Mrs C Remembers, characters who people it and its politics

In Mrs C Remembers (Pan Macmillan India), her first novel for adults, Himanjali Sankar explores “the limits of submission, of illness and upheaval and the unfathomable powers of the human mind.” It is the story of Mrs Anita Chatterjee, wife to one of Kolkata’s most successful men, and her daughter Sohini, who is an artist living in Delhi with an unconventional partner.

Sankar has worked with various publishing houses and is currently an editor with Bloomsbury India. Two of her books, The Stupendous Time Telling Superdog and Talking of Muskaan, were shortlisted for the Crossword Award for Children’s Literature.

Sankar says she wanted to write about a woman who had dementia. “I don’t mean to romanticise and say the story wrote itself but that is what happens so often — the story comes out with all its frailties and we edit to see what is required and what isn’t. I found that the politics and social commentary was as important to me as Mrs C’s story, rather it was integral to who she was, so it had to stay,” she says. Excerpts from an interview:

Shireen Quadri: Mrs C Remembers is your debut novel after three books for children. It’s a novel shaped by the times we live in. Did you set out to write a story with contemporary social and political overtones?

Himanjali Sankar: I think many of us today feel the margins between the social, political and personal are getting increasingly blurred — perhaps social media (amongst a host of other factors) is partially responsible for that. In any case there’s no question that we are living in a fraught polarised world. I wrote the first chapter of this novel without thinking or planning anything one Sunday morning — it read almost like a short story. But it set the tone for the rest of the book. Strictly speaking, I was writing about a woman who had dementia. I don’t mean to romanticise and say the story wrote itself but that is what happens so often — the story comes out with all its frailties and we edit to see what is required and what isn’t. I found that the politics and social commentary was as important to me as Mrs C’s story, rather it was integral to who she was, so it had to stay.

Shireen Quadri: The novel, at some level, is enmeshed in the constructs of memory and forgetting. Were you interested in exploring the various ways memory works?

Himanjali Sankar: Totally. You know the way the same event is so often experienced very differently by two people? Like a dead dog lying on the roadside — it disturbs some people, unspooling their minds in weird ways, while some are completely unaffected by it. And memory implies a further distillation with the passing of time. What a person chooses to remember and what one chooses to forget. Add to this a neurological disease that entails forgetting — which makes so many years, moments and months vanish. Who makes the selection and how, of what we remember and what we forget? I really have no answers but it does throw up so much. And what are novels if not the thoughts, memories and ideas of the writer — ordered and structured to tell a story.

Shireen Quadri: Did you set out to write about three generations of women and how they look at their family and the world around them? Is Sohini emblematic of an attitudinal change? How inextricably is that linked to her generation?

Himanjali Sankar: My intention was to tell only Mrs C’s story. The generation before hers and after was important only so far as they impinged on her narrative. Though, yes, Sohini’s voice is important and even if I didn’t intend to make her emblematic of an attitudinal change it might come across that way because that’s how our lives move and change incrementally from one generation to the next. The changes in Sohini’s life are related to the social-political-cultural changes of her times which are significant in so far as they affect her life — they aren’t the primary focus of the novel.

Shireen Quadri: An important theme of the novel is the submission of women and you capture this through Mrs C’s devotion to her mother-in-law and her husband. Does Mrs C’s compliance come from her conditioning? Does it have to do with a particular generation?

Himanjali Sankar: Yes, well, conditioning is what dictates how we approach gender roles and behaviour and they were defined in a certain way in that generation (across classes and communities possibly). But the personal is important too — it determines the extent to which a person is meek and submissive, or negotiating for change, directly or otherwise (negotiating for change doesn’t necessarily mean challenging the status quo). In Mrs C’s case, she is submissive but protective when it comes to her daughter. There are some common characteristics that each generation shares and since Mrs C and Sohini belong to different generations, some generic changes in approach to gender and identity are inevitable (apart from those dictated by their individual personalities) and their mindsets and attitudes will be, apart from other factors, deeply reflective of their times.

Shireen Quadri: How important are the other minor characters, like Sanchita and Omar?

Himanjali Sankar: I suppose they are minor characters, but they are special and relevant. I revealed as much of them as was required for Mrs C’s story but their ways of thinking and being influenced the main characters enormously and in that they are important.

Shireen Quadri: The novel also lays bare the hypocrisy in the society and embracing the ‘other’ which find a resonance in today’s India. Were you interested in exploring these aspects too?

Himanjali Sankar: Yes, I find the different ways of negotiating with the ‘other’ can tell us a lot about ourselves. How sometimes certain relationships like friendship are acceptable but boundaries are drawn for marriages/relationships. Or in the way we make an exception for a close friend but hold the rest of the community culpable. Though this hypocrisy might not be harmful in itself except if stretched to its limit — when we see incidents of ostracisation or honour killings for instance. In its lesser manifestations, they can also be a problem in offices and schools where kids can reflect their parents’ ways of thinking (leading to bullying, etc). Then, finally, there is the more outright intolerance of the other (lynching and rioting in the name of religion) which is also becoming dangerously acceptable these days.

Shireen Quadri: The novel is also a meditation on gender and the roles it preordains. Was it crucial to the plot?

Himanjali Sankar: Gender relationships and roles were crucial because they are pivotal in traditional families and Mrs C and Sohini belong to the sort of society where one’s primary identity is derived from gender. Mrs C’s personality and attitude is completely defined by the gender expectations imposed upon her by society and by herself.

Shireen Quadri: Was it important to tell the story in the voices of the two women — Mrs Chatterjee and her daughter Sohini?

Himanjali Sankar: Mrs C’s voice is the most important one but the second one could have been her son too — just that I naturally gravitated towards the daughter. Though come to think of it, it might just have been interesting to, say, use Omar’s voice instead of Sohini’s. What probably stopped me was my fear that I wouldn’t be able to do justice to him — it wouldn’t have come to me as easily so it might have lacked veracity or been a little artificial. And it would have been a very different book then! Fundamentally though, that wouldn’t have altered what is being said in the book.

Shireen Quadri: What are you working on next?

Himanjali Sankar: I don’t know, but I would like to step a little out of my comfort zone the next time, write something that requires some background research and rigour perhaps. I love the idea of writing crime.

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated