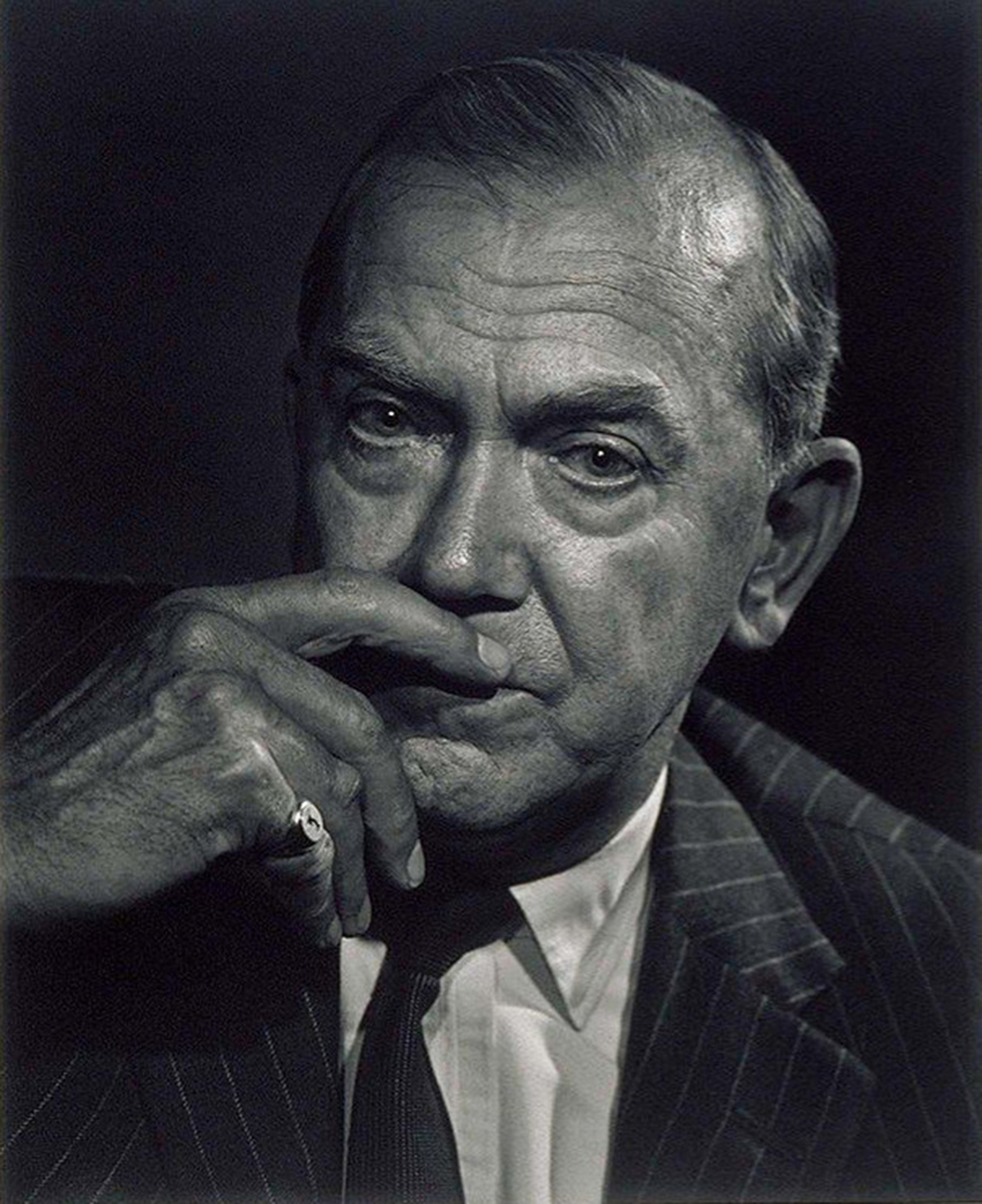

Graham Greene. Photo courtesy: Yousuf Karsh

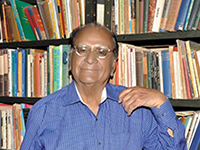

Snatches from an unpublished conversation with Graham Greene (1904-1991) by Professor Shiv K Kumar (1921-2017), poet, playwright, novelist and short story writer. Before his death, Kumar had graciously given us the permission to carry it

Henry Graham Greene was born on October 2, 1904 at Berkhamsted, Hertfordshire, England. During his schooling at Berkhamsted School, where his father was headmaster, he made several attempts at suicide by taking a heavy dosage of aspirin. Being a manic depresso, as an undergraduate at Balliol College, Oxford, he led a solitary life, avoiding the company of his college mates.

Evelyn Waugh, one of his contemporaries, observes that Graham Greene looked upon his contemporaries with disdain. For a short while, he was a member of the British Communist Party. After his graduation he worked for a short period as a private tutor, then joined first on the Nottingham Journal and later joined The Times as its sub-editor. While at Nottingham, he often lapsed into long spells of agnosticism. But when he started corresponding with Vivien Dayrell Browning, a catholic convert, Greene adopted Catholicism as his mode of belief. His interest in Catholicism deepened when he intended to marry Vivien who brought him to a state of poised belief in God. In 1926, he was baptized as a catholic and then he married Vivien the next year.

Although he separated from her, he never divorced her although he had other emotional relationships. He chose to leave England when he was financially cheated by someone and settled in Antibes, south of France where he continued romantic relationship with Yvonne Cloetta till his death.. In recognition of his literary eminence, he was honoured with Order of Merit and Companion of Honour. In 1967, he ran as a candidate for the Nobel Prize for Literature but was disappointed when a British member of the Swedish jury voted against him. Greene is known for his statement (observation): “In human relationships, kindness and lies are worth a thousand truths.” He died on April 3, 1991 at the age of 86 in Vevey, Switzerland.

It was during my visiting professorship at Franklin Marshall College, Pennsylvania, that I decided to write to Greene. I had included in my course on “Contemporary British Fiction”, his novel The End of the Affair. This novel had been effusively praised by William Faulkner who thought that this was the best novel he had ever read.

I had just completed the manuscript of my second novel Nude Before God, and was looking for a publisher in the USA or UK. It was in this context that I thought of Greene. If he had launched R. K. Narayan on his literary career by applauding his novel Bachelor of Arts, I wondered why I too couldn’t seek his patronage. So I decided to send him a letter saying that I had taken up The End of the Affair for detailed discussion in my class. I wrote to him that this novel had intrigued me for its handling of miracles which could be actual happenings or mere coincidences. I perceived that the protagonist in this novel, Bendrix, was Greene himself. I mentioned that I had written a novel on the departed soul of a man whose wife had a paramour. I hoped he would find some time to read this manuscript and send me a word of encouragement.

I knew that my letter to Greene was like an arrow shot in the dark. Although I didn’t expect any response from him, I’ve always believed in the utter unpredictability of life.

Surprisingly, I received a letter just a few days later from Alice Hamilton, his secretary in London. Very politely, she said that Mr Greene might not find any time to read my manuscript as he was deeply embroiled in a libel case in Paris. Nonetheless, she offered to forward my letter to him at his villa in the south of France

I took it as a miracle when I received a letter from Greene himself that he would be happy to read my manuscript, but I would have to give him at least three months’ time.

Promptly, I wrote back: “Miracles are not just coincidences because they do happen at times. Isn’t it a miracle that you have so very graciously agreed to read my manuscript? You have asked for three months’ time, sir, when I should be too happy to let you have a whole year. I’ll wait patiently.”

A fortnight later, he wrote back.

I was catapulted into ecstasy. In regard to the title, I didn’t tell him that I had changed the title to Nude Before God. I was disappointed to realise that I had missed the prize because this was not my first novel.

Meanwhile, I was fortunate to pick up an acceptance from an American publishing house which had published the earlier novels of Saul Bellow and the first novel of V.S. Naipaul. So when I received Greene’s letter, I sent a copy of it to the publisher who wrote back asking me to request Greene for a quote to be splashed across the jacket cover. So, I wrote another letter to Mr. Greene to which he responded.

I sent a cable to my American publisher and the following week an ad appeared in The New York Times on its editorial page quoting Greene.

That was the beginning of my affair with Greene. I realized that it was only truly great people who can be generous enough to encourage unknown writers like me.

I did write to him, however, that I’d be immensely pleased to meet him in London or New York if he ever happened to visit either of these two cities. I had scraped up a little money and was ready to fly to London to meet him. His secretary informed me that he would be in New York in the third week of November and would be delighted to have me over for lunch. She added that he would be staying at room no: 905, Hotel Waldorf Astoria, on Manhattan Street. I responded immediately that I'd be delighted to meet him there.

Excited as I was, I decided to be in New York a day before our meeting.

I was at the hotel about noon time. I gently knocked at his door. There was Greene to welcome me. He asked me to sit on the sofa next to him and we started conversing.

“How do you find your teaching assignment at Franklin Marshall, Mr. Kumar?” he asked me “Quite rewarding,” I replied, and then added with a smile on my face, “Not academically though, but financially. You know that a degree in English literature from any British University, especially Cambridge or Oxford still sells in the American market.”

“I understand,” he said, genially.

There was a brief spell of silence and then I resumed, “Last semester, I offered a course in modern fiction with particular reference to your novel The End of An Affair and Joseph Conrad’s The Heart of Darkness.”

“Of course, I remember you writing to me about the miracles in my novel. It is all to do with marketing. I haven't told you that I've come to New York at the invitation of my publisher's in New York, to promote my. novel. So, in a sense, I’m on a business tour. But business with pleasure —. business to market my books and pleasure to meet someone from a country I love and admire.”

“Thank you, Mr. Greene.” Then, after a pause, “Of course, I remember you mentioning in one of your letters to R.K. Narayan, one of our leading Indian English novelists. But I couldn’t quite understand what you said about his possible reaction to my novel as an orthodox Hindu.”

“I just imagined that he wouldn’t have liked certain bold bedroom scenes in your novel. He seems to be a gentle, sober individual.” But, instantly, he added with a smile, “Not that you’re too bold and invasive. You know, I really liked your book.”

“Thank you. Your handling of miracles in The End of an Affair prompts me to ask you something, if you please. Did it have something to do with your conversion to Catholicism? I remember reading somewhere that like Cardinal. Newman, you accepted Catholicism because it’s a religion of faith.”

“You’ve understood me, quite correctly. Protestantism was too critical, too questioning, and too rational. I had come to a stage in my life when I wanted to surrender my reasoning faculty to a Will above and beyond any ratiocination. And this is what I found in Catholicism, and this is what prompted me to present Sarah in my novel as someone who became a deity after her death. You may remember how in my novel I’ve said that people came looking for heirlooms, a strand of hair or anything from her body that they could walk away with.”

“That was the most touching part of your novel,” I said. “This time it’s my turn to share with you something about my religious belief. I wonder if you’ve heard about Arya Samaj which is a branch of Hinduism. My father was a staunch Aryasamajist, and, therefore, he relished debunking all other religions except the Aryasamajist’s faith propagated by Swami Dayanand. His bible was the book written by this Swami titled The Light of Truth which he wanted me to read again and again and ponder over. But I found the last section disturbing, where the Swami criticized Christianity, Islam, Jainism, Buddhism, and Sikhism. I used to ask my father as to why one should not accept religion as a matter of faith, without crossing swords with other religions. The more my father pushed me into Aryasamaj, the more I revolted the Swami’s model .of criticizing other religions. So, like you, I kept my reservations to myself without, of course, converting to Vaishnavism or the Bhakti saints.” I took a deep breath and added “You know, my philosopher Henry Bergson also converted himself from Judaism to Catholicism, because he also, like you, wanted to accept belief as a matter of faith.”

“So we’re all in the same camp, Mr. Kumar — Bergson, Newman, you and myself.” We had a good laugh together.

“Since I look upon you as my guru, may I please ask you if your novel The End of an Affair is autobiographical? You know, your use of diary notes, and the first person singular, made me believe that this mode of writing is based on personal experience. You may have noticed in the manuscript I sent you, that I wrote this novel in the first person singular. But being a timid man, I added a foreword to this novel in the form of a letter saying that it was not my story, but of the protagonist.

Smiling, he said, “You don’t have to camouflage yourself, Mr. Kumar. If there was no Muslim woman in your life, there might have been a Hindu, a Christian or a Sikh woman who attracted you irresistibly. As for myself, let me be honest with you that my novel is substantially based on my involvement with a young woman — not Sarah, but who carried another name. Let’s keep it all a secret. It was the authentic emotion behind this novel that brought me a glowing tribute from Faulkner that this was the best novel he had ever read. Indeed, the first edition was sold in just a few days and the book still keeps snowballing.”

It was now time for Mr. Greene to order lunch in the room itself. I’d already prepared myself to tell him that I was a vegetarian. As he was ordering the meal over the phone, I said, “No meat for me please. Like your friend, R.K. Narayan.”

“I understand you. May be you inherited vegetarianism from your orthodox father.”

“You got me right. But, I wouldn’t mind a small glass of beer just to keep you company.”

“That’s great, Mr. Kumar. Let’s have some beer together then. You know Americans have not been able to brew any good beer in this country. They still import Beck or Budweiser from Germany. So let me order some Beck which, I’m sure, you would relish.”

A couple of beers was followed by lunch. I resumed my conversation with Mr. Greene. “Why don’t you consider visiting India? I’m sure Mr. Narayan must have invited you already.”

“Indeed, he did tempt me to visit at least Mysore and Madras which seem to be his native territory. But although I have travelled extensively, I couldn’t make it to India. The nearest I got to India was a brief stay in Colombo where I prayed at a Buddhist temple on my birthday which happens to be the same as Mahatma Gandhi’s — October 2. That prayer gave me a lot solace.”

“Two great minds with the same horoscope.” I quipped..

“No no, I’m nowhere near your Mahatma who is one of the greatest things that happened to mankind during this century. I remember what Bernard Shaw said about the Mahatma, ‘For generations to come, people would scarcely believe, that such a man as Mahatma Gandhi walked across the face of the earth in flesh and blood.’”

“That was a great tribute paid by Shaw to the Father of our nation, even though Shaw was something of an iconoclast. But even the devil has his moments of affirmation.”

I thanked him profusely for his hospitality and left. I told myself that it was a great experience to have spent some time with one of the greatest British novelists. Thereafter, we carried on our conversation, if not personally, but through letters that we exchanged with each other.

I felt hurt when I read an article in The New York Review of Books how Mr Greene missed winning the Nobel Prize. The writer of this article mentioned how there was an Englishman on the Swedish academy who never took kindly to Mr. Greene, and shot him down from the list of runners-up to this prestigious prize. I wrote a letter to Mr. Greene saying that I took it as a great disappointment for me to see how the greatest novelist of his time was denied his due recognition. But life has its own ironies and, in any case, it’s not a prize that is all a writer may look for in life, it’s his work, and, often, the work transcends any material recognition that might come in the way of a writer.

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated

In what year did Prof. Shiv Kumar interview Graham Greene? I can't see it mentioned in the article

Karnarajsinh Vaghela

Jun 18, 2019 at 13:33