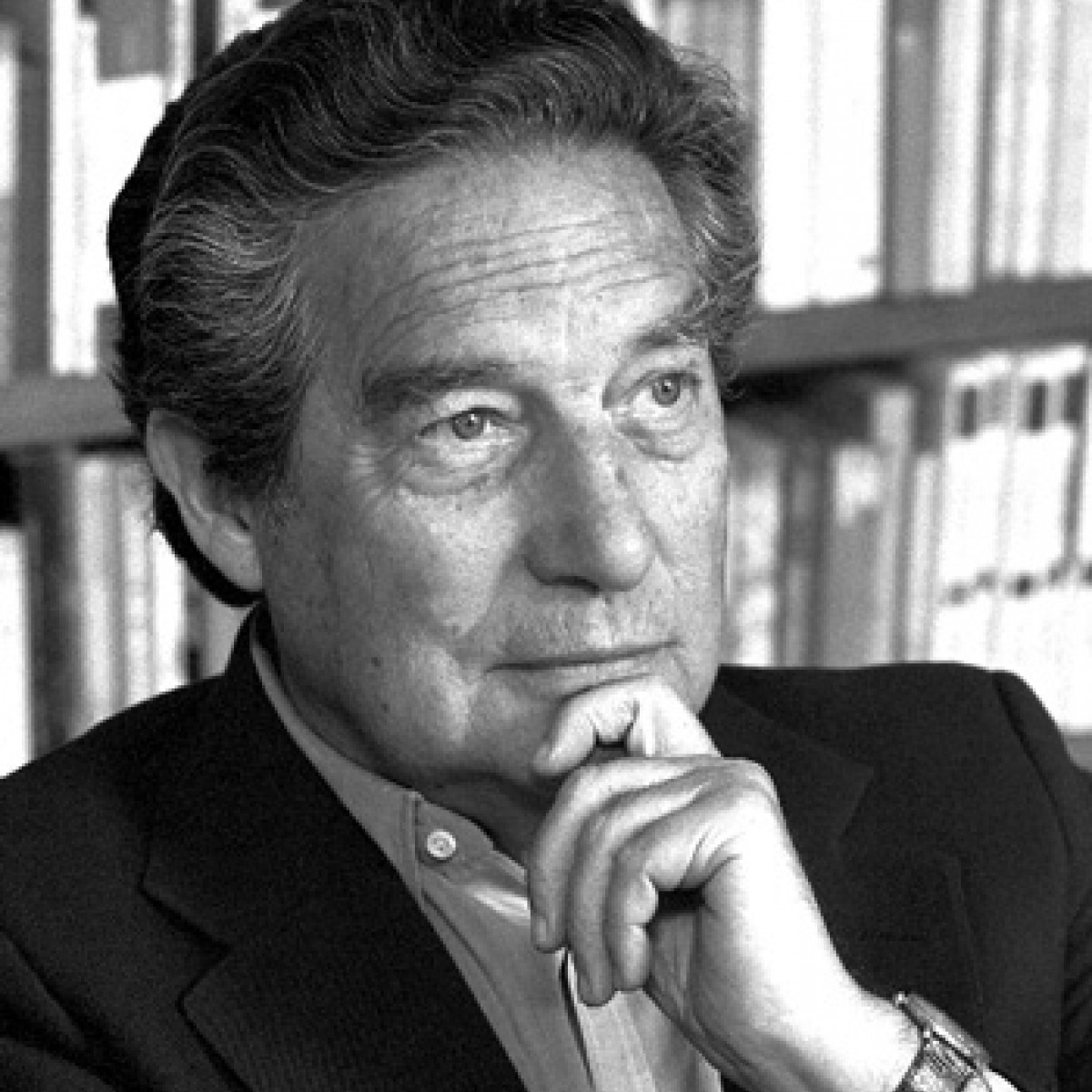

Octavio Paz Lozano was born on March 31, 1914 in Mexico City, Mexico. He studied at Colegio Williams. Since his family supported Zapata, they went into exile in the USA after Zapata’s assassination. Octavio was introduced to literature by his grandfather’s library which carried books on Mexican and European Literature. His earlier writings were also influenced by Gerardo Diego, Juan Ramon Jimenez, and Antonio Machado, Spanish writers. His earlier poems, including Cabal/era were published under the influence of D .H. Lawrence who was himself an admirer of Mexican art, culture and literature. Later he published his Wild Moon (Luna Silvestre) which brought him literary acclaim. In 1932, he edited a literary magazine Barandal which encouraged several younger Mexican writers. By 1939, Octavio had shot into literary limelight as an outstanding Mexican poet. In 1935, he taught at a school in Merida which was meant for children of the labor class. His liberal humanism is evident from his long poem, “Between the Stone and the Flower,” influenced by T.S. Eliot. The poem articulates the plight of the Mexican peasantry under the avaricious landlords. In 1937, he was invited as a delegate to the Second International Writers Congress in Defense of Culture in Spain, where he exhibited his solidarity with the Republicans who were protesting against Spanish fascism. On his return from Spain, he launched another literary magazine Workshop (Taller) which carried poems, essays and stories by contemporary writers. In 1938, he married Elena Garro, considered one of Mexico’s renowned writers (whom he divorced in 1959 to marry the Italian painter Bona Tibertelli de Pisis).

In 1943, Octavio received a Guggenheim fellowship which brought him to the University of California at Berkeley, and later was inducted into diplomatic service. In 1962, he was appointed Mexican Ambassador to India. In Delhi, he associated himself with Indian writers, particularly a group of writers known as “Hungry Generation” and had a deep influence on them. From 1970-1974, he was distinguished faculty at Harvard University where he occupied the Charles Eliot Norton chair. Subsequently he was awarded the Jerusalem Prize for literature followed by the Neustadt International Literary prize at Norman, Oklahoma. He won the Nobel Prize in 1990 which was a culmination of his literary eminence.

Listed below are some of his outstanding publications:

1) Alternating Current (tr. 1973)

2) Configurations (tr. 1971)

3) The Labyrinth of Solitude (tr. 1963)

4) The Other Mexico (tr. 1972)

5) El Arco y la Lira

6) The Bow and the Lyre

7) Early Poems (1935-1955)

8) Collected Poems: (1957-1987)

Octavio Paz is known for his glowing tribute to poetry: “There can be no society without poetry, but society can never be realized as poetry, it is never poetic. Sometimes the two terms seek to break apart. They cannot.”

He died of cancer on April 19, 1998 at the age of 84 in Mexico City, Mexico. Here are excerpts from a conversation with him I had in 1982 after he was declared the winner of the Nobel Prize:

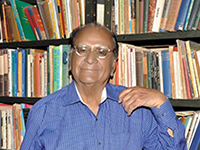

A more handsome man than Octavio Paz I’d never seen. He was tall, with a dusky complexion, broad forehead, dark glossy hair parted in the middle, and eyes that sparkled with insatiable curiosity. His face was sculpted like a Greek god’s. But handsomer than the man was his poetry, charged with intense emotion, striking images and metaphors, and a rhythm that flowed like a gentle stream.

I first met him in 1982 at Norman where I was Visiting Professor of English Literature at the University of Oklahoma. During my stay there, Ivar Ivask, chairman of the International Neustadt Literary Prize, set up jointly by the Neustadt Foundation and the University, invited me to act as one of his Jurors. When Octavio Paz was declared winner for the 1982 prize, a banquet was hosted in his honor. Ivask introduced me to him as a poet and academic from India. I was excited to be seated next to him at the High Table.

“How I wish I'd met you in Delhi,” I started off, “when you were the Mexican Ambassador to India.”

“Time and place are decided by the gods. It’s all written m our horoscopes.”

“You speak like an Indian Sage,” I said.

He nodded his head. “Maybe. during my stay in India, I got to read The Gita, and The Mahabharata and The Ramayana.'

“Mr. Paz, you seem to have enjoyed your stay in India,” I said, leaning towards him.

“Enjoy?,” he said the word emphatically. “I found everything about India fascinating — the Himalayas, the river Ganges, the temples, and the dark monsoon clouds scudding through overcast skies.” He pursed his lips, a thoughtful expression on his face. “But what fascinated me most were your women, with their long glossy hair, doe-like eyes, and draped in sarees that exposed their navels. It was so tantalizing, so very seductive! It was as if they had stepped out of the murals of the Ajanta and Ellora caves.”

“They must’ve found you fascinating, a handsome man and a poet,” I said with a smile.

He shook his head. “I don’t know. I thought most of them were like shy birds would fly away at the mere thought of touching them.'

“On the contrary, our city women are bold and fearless.” After a brief pause, I asked him, “Mr. Paz, why don’t you plan to visit India again? The postman rings the bell twice.”

“No, there’s only one ring. The second one is always a fantasy. Moreover, I’m presently busy working on a new collection of poems.”

“I have a question, Mr. Paz. Do you find the English translations of your poetry in Spanish satisfactory?”

“No,” he was emphatic, “poetry can never be truly translated from one language into another. It’s like transplanting a rose.”

I suddenly realized I had monopolized him all this while when I saw a couple of guests standing behind him, waiting to have a word. I decided to end our conversation. “May I, please, meet you in your room at the hotel. I find talking to you most stimulating.”

“You are always welcome,” he said. “How about six o’ clock tomorrow evening?”

The next morning, I looked through his Collected Poems. The best compliment to a poet is to recite from his poetry. In the evening, when I met him at the hotel, I found him seated at a large table arrayed with a variety of liquors — wine, whisky, vodka, gin, and champagne.

“How about joining me for a drink, Mr. Kumar,” he said, pointing to the liquor bottles. “I recommend our Mexican wine with its distinctive flavor.”

“Very gracious of you”, I shook my head, “but I am a teetotaler, with no meat either. An abstemious puritan you may call me.”

“Never mind, I have met several Indians like you who take just soft drinks at parties. Well, you may try some tea and snacks.” He leaned forward, resting elbows on the table.

The bearer came with the tea service and snacks. Octavio Paz poured himself a large glass of wine. “How I wish you could have shared with me this Mexican wine. It’s a brew fit for the gods. But I wouldn’t like to compel you.” As I sat drinking tea, he immersed himself in his wine. And we got into a lively conversation. I told him, “I’ve adopted you as my guru. There is so much to learn from your poetry. I admire your craftsmanship with the scintillating images. And there is the rhythmic flow of words with its lilting cadence.”

“Your generous praise embarrasses me.” After a brief pause, he asked, “I should like to know which of my poems has worked for you the most. It’s every poet’s desire to get feedback from his readers, especially from a fellow poet.”

My response was spontaneous. “My favorite poem by you is “As One Listens To The Rain”. I can even recite parts of it from memory”. I declaimed,

“Listen to me as one listens to the rain, not attentive, not distracted,

light footsteps, thin drizzle,

water that is air, air that is time, the day is still leaving,

the night has yet to arrive,

figurations of mist

at the turn of the corner, figurations of time

at the bend in this pause,

listen to me as one listens to the rain, without listening, hear what I say

with eyes open inward, asleep

with all five senses awake”

“Amazing,” Paz said, astonished, “how you remember a long part of the poem! I am honored.”

I returned the compliment. “It baffles me how you could give those twists and turns in the third and fourth lines of the poem. It is magical!”

“It’s my favorite poem too. Let me tell you, this poem almost wrote itself. I revise my poems several times, but this was the piece I thought didn’t need any revision. How about you, Mr. Kumar? Do you revise your poems?”

“Oh yes! Several times. In this respect, I am like Dylan Thomas who used to revise each poem seventy-eighty times.”

“Indeed, revision is necessary. I believe revising a poem is a creative exercise in itself.”

While we were talking, I heard the windows of his room rattle. For a brief moment, a flash of lightning shone bright behind a windowpane, and it started drizzling. I realized that I’d lost him in the course of our conversation for his eyes were focused on the windowpane. He was watching the raindrops chase each other like gold fish in an aquarium.

I felt the raindrops were weaving patterns of parabolas and ellipses in his imagination. Octavio Paz’s eyes were glowing like embers. Was it the Mexican wine or the intensity of his imagination, I wondered. It took him some time to return to the outside world. Octavio Paz slowly poured himself another generous peg of the wine. Finding him in a genial mood, I brought out a copy of my collected poems Woodpeckers from my bag.

“May I, please, present you a copy of my collected poems published a couple of years ago. In it there is a poem titled “Indian Women” which presents a different picture of women in India. In our last meeting, you spoke of the modern women with whom you interacted in Delhi. Different from the city women are the women living in the villages. They are known for their devotion and commitment to their husbands.”

I opened my book at the page where the poem was printed for I was eager to know what he had to say about it. Paz gave it a close reading. “This is a beautiful poem. I like the way you describe your country as a triple baked continent. The womenfolk of the village are shown as coming to terms with their loneliness. They don’t draw angry eyebrows on the mud walls, but instead wait for their husbands to return.”

“Thank you, Mr. Octavio Paz. I’ll always remember your gracious words,” I said. I got up to leave because I felt I’d taken too much of his time. I told myself silently that the great poet should be left alone to dream; to write; and to observe the dance of the raindrops on the windowpanes. We parted with a warm handshake, not knowing when we would meet again.

Years later, in 1990, when I heard the exciting news that Octavio Paz had been awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature, I said to myself, “This is the least the world could’ve done for him.” I wrote him a letter saying how happy I was to hear about the honor done to him. An honor which he richly deserved.

In his reply to my letter all that he said was “Mr. Kumar, my privacy .. would be now up for grabs. Would I’ve the time to watch the raindrops on the windowpane, with interviewers not leaving me alone? Only a fellow poet like you can understand that a writer is essentially a loner.”

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated