Introduction

Edward Morgan Forster was born on January 1, 1879, at Marylebone, London. He attended the famous public school Tonbridge School in Kent as a day scholar. Later, he became a member of the Discussion Club at King’s College, Cambridge, which honoured him as its honorary fellow. He lived a major part of his life in his rooms at this college.

He first visited India in 1914 and was enamoured with Indian culture. When the First World War broke out, he protested openly against the war as a conscientious objector. He again visited in 1920 and worked for some time as private secretary to Tukojirao III, the Maharajah of Dewas. He also travelled widely all over the Indian continent and made several friends. He donated a sumptuous amount towards the building of the Urdu Hall in Hyderabad as his tribute to Islamic culture.

His fiction is known for his humanism, symbolism and homosexuality. He valued human relationships above everything else. In his essay on “Two Cheers for Democracy,” he observed: “If I were to choose between betraying my country and betraying my friend, I'd have the guts to betray my country.” This statement created a furore in England because most people misconstrued it as a literal statement, questioning his patriotism.

E. M. Forster never married but is known to have homosexual relationship with Bob Buckingham — a theme which also inspired his novel Maurice. His credo of life appears as an epigraph to Howard’s End —Only Connect. For his literary achievements, he received several awards, including Order of Merit and Benson award. Several of his novels, particularly A Passage to India, were made into movies Forster died of a stroke in Coventry on June 7, 1970, at the age of 91, at the home of the Buckinghams, Warwickshire.

It was a chilly winter morning, with snow heavily layered on the streets and lanes of Cambridge. The wind howled all around. But in spite of this inhospitable weather, I decided to wade through the snow to get to the Saturday market behind St. Mary’s church. I never missed my weekend shopping at the market where I purchased my provisions at bargain prices — milk, vegetables, bread and fruits. Being one of the poorest students at the university, I had to scrape up every penny to keep myself going.

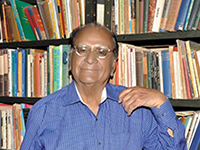

After I’d done my shopping, I walked over to a book stall in a corner. I saw people buying second hand books at throwaway prices. Only the previous week I had got a rare book bargain — Stephen Spender’s Collected Poems, with an inscription in the poet’s own hand, “To Natasha, with love”. As I was browsing through the books there, I noticed an old man bundled up in a woolen overcoat with a Russian fur cap on his head and hands in leather gloves. I instantly recognised the man whose photographs I’d seen in several books and magazines. Surely, it was E. M. Forster, the renowned author of A Passage to India. I felt a strange sensation down my spine as I drew close to him. “Am I speaking to Mr. Forster, please?” I asked softly.

“Yes, you are. What’s your name, young man?” he asked.

“Shiv K. Kumar,” I said.

He exclaimed, “Oh! Lord Shiva, the God of annihilation of evil. So you are from India.”

“Yes, Sir. Though I may claim to be a Pakistani as well because I was born in Lahore. I crossed over to India as a refugee at the time of the Partition.”

“You must have had a traumatic experience, harrowing and shattering.”

After a brief pause, he spoke again. “I should like to meet you over a cup of tea in my rooms at King’s, where I live as an Honorary Fellow. My rooms face the King’s Chapel across the lawn. You may ask the security guard at the main gate. He’ll bring you up to my rooms.”

“So gracious of you, Sir, to invite me to tea. I’ll be there tomorrow afternoon. For me, it’s a dream come true. Thank you very much.”

Since I’d been told by my friends that an Englishman is known for his punctuality, I decided to reach the main gate half-an-hour early. Instead of looking for his rooms on my own, I sought the help of the security guard on duty. Mr. Forster’s rooms were on the first floor, so I climbed up the steps and stood outside his door, looking at my wrist watch all the time. As soon as it was 4.30 p.m., I gave a gentle knock on the door. My host appeared at the door dressed informally in shirt and trousers. “Come in, Mr. Kumar,” he said. I was invited to take a seat near a logwood fire which exuded warmth and comfort. It was in stark contrast with the frigid atmosphere outside.

“Would you care to have some coffee or tea?”

“I’ll take some tea, please,” I said, accepting the invitation. I added facetiously, “To be honest, as I’m a milk baby, I don’t usually take either tea or coffee. But please don’t bother to get me milk.” I paused for a brief moment. “Sir, I’m a vegetarian and a teetotaler. It has almost made me an outcast at Cambridge. But I’m getting along somehow.”

E.M. Forster smiled. “Indeed, I’d several friends in India who were like you. No meat and no drinks.”

“Let me share a secret with you, Sir. It may explain why I came to the Saturday market to buy my groceries. It is because I do my own cooking. Before I came to England, my mother gave me several lessons on how to cook lentils and bake chapatis.” With a deep breath, I added, “You must try my food some day.”

“Certainly, I’ll come over to visit your lodgings.”

I suddenly realised that I’d slipped up in inviting him to my lodging which was in a dilapidated old building on the verge of collapse. It was the cheapest place I could rent at Cambridge. My rooms didn’t have central heating, and I’d have to use hot bags under my quilt to keep myself warm at night. Every morning, I would have a glass of milk, and a toast with butter or margarine. I would then take the long walk to the university library which offered me comfort and warmth from morning till evening. My days were spent in the Anderson's Room which was reserved exclusively for research scholars.

“Have you come here to study the Tripos or to pursue research?,” asked Mr. Forster as we sat sipping tea.

“I am pursuing doctoral research on ‘Bergson and the Stream of Consciousness Novel’. I don’t know if I’d ever be able to get to the end of my project.”

“A tough subject.” He shook his head sympathetically. “I assume you’d be writing about James Joyce, Virginia Wolf… and who else?”

“Dorothy Richardson,” I gave the name.

“It’s going to take a while for you to complete your thesis. You seem to have put your fingers into a blazing oven. You know, I once tried to make sense of Joyce’s Finnegans Wake. I couldn’t advance beyond the opening paragraph. Also, his Ulysses is a bizarre narrative. But you seem to be a strong-willed young man. You should be able to handle this subject with skill and determination.”

He paused to look at my face closely. And then he came up with a question. “But what about Bergson? I assume you’ve a background in philosophy.”

“No, Sir, I don’t. You’d be surprised to know that I never did philosophy throughout my school and college career. I did science at the intermediate level. History and political science were my auxiliary subjects at the graduate level. And, of course, English Literature for my Master’s.” “Amazing,” he ejaculated. “But then you Indians are born philosophers. During my stay in India I noticed that even rickshaw-pullers talk about karma, retribution and detachment. I remember once engaging in a conversation with a taxi driver on karma and rebirth. I’m sure you’d turn Bergson around your finger with confidence.”

“Thank you, Sir.”

“Incidentally, who is your supervisor?”

“Dr. David Daiches who has just joined Cambridge.”

E.M. Forster nodded his head. “I know him. Surprisingly, Cambridge did not recognise his doctorate from Oxford. Just because that university is ‘the other place’. You may have read somewhere what I've said about Cambridge and Oxford. While Cambridge has preserved the virginity of its beautiful campus, ‘the other place’ has become its bloated sister, with several industrial units located on the outskirts. Cambridge is still beautiful like a sylvan village with its Cam, ‘the smoothest of all rivers’, to quote Milton.”

I said, “I’m very fortunate to be here at this university where I can do research in modern literature. Oxford is limited only to the classics.”

Forster gave me a less-known fact. “I haven’t told you about what had happened to your supervisor. When he was listed as Mr. Daiches in the faculty list published by Cambridge, he felt anguished. He was so upset that he wrote an interesting article in The New Yorker titled ‘A Matter of Degree’. To address his grievance, the University conferred upon him an honorary doctorate so that he could be designated as Dr. Daiches.”

I exclaimed, “I’m surprised how I didn't know this. I respect Prof. Daiches, and I'm looking forward to completing my thesis under his supervision.”

It struck me suddenly that we’d both drifted away from my main objective. It was to interview him for The Illustrated Weekly of India so that I could pick up a little extra money. When I told him about my desire to ask him about his experiences in India, his face glowed. “I guess you propose to write about our conversation.”

“Yes, Mr. Forster. If you’re gracious enough to help me write this interview article, I’d be able to pick up some twenty pounds from an Indian magazine.”

“Then start firing away, Mr. Kumar.”

“I’ve a question for you Mr. Forster. In A Passage to India, what happens in the Marabar caves when Dr. Aziz is alone with Adela Quested. That scene has always intrigued me. My Indian readers would like to have your response.”

He beamed, and there was an impish sparkle in his eyes. “Why don’t you tell me? I don't have a clear answer to your question.”

“I guess, like every great artist, you deliberately chose to let this scene remain wrapped in mystery. Mr. Forster, let me ask you another question. During your stay in India, did you feel more comfortable interacting with Hindus or with Muslims? I believe your heart is with Dr. Aziz, and not with Godbole. You portray Dr. Aziz as a sensitive young man who enjoys reciting poetry, whereas Godbole is a caricature of Brahminism. You show him muttering such chants as ‘Tukaram, when will you come?’”

Forster shook his head. “No, I’ve no prejudices for any community. But you seem to have an incisive mind. I admit I’ve a lurking sympathy for Dr Aziz whom I’ve based on someone I knew in Hyderabad. I’ve dedicated A Passage to India to Dr. Masood who was the Director of Education in the Nizam’s State of Hyderabad. I donated some money towards the building of Urdu Hall which is located in the Himayatnagar area of Hyderabad. Though I never cared to learn Urdu or Persian, I love those languages for their musical resonance, but Hindi and Sanskrit are Greek and Latin to me.”

“Mr. Forster, I’ve seen your photo from the time when you were secretary to the Maharaja of the Devas State. You do look princely in the court attire.”

Forster smiled. “Yes, I wanted to be taken for an Indian Prince.”

“And how did you take to Indian food?,” I asked him.

“I love rice biryani, roasted chicken and the parathas, your Indian bread. But what has captivated my heart is the mango. Last month, an Indian scholar from Jaipur brought me ‘Jahangiri’ mangoes that kept me hooked for a whole month.”

This brought me to the end of my conversation with him. As I got up to leave, my eyes studied his library. I noticed a vast collection of books kept on the shelves.

“May I have a look at your books, please?,” I asked.

“Go ahead, it’s all open to you. You may take a look at my collection of books on India.” Pointing his finger at a pile of books kept in a comer, he said, 'That is my special collection which I pride above everything else.” I noticed that he had books on Indian architecture, folk songs and travel. There stood on a separate table a book bound in Morocco leather titled The Case For India by Will Durant.

I was very happy to find a British writer who was in love with my country. As I walked back to my chair, I noticed a large piano kept near the coffee table.

“Do you play the piano, Mr. Forster?” I asked him, prompted by curiosity.

“Yes, I do,” replied Forster, “although I can’t claim to be a pianist. I just enjoy letting my fingers ripple over the key board. The music helps me forget my worries. And, about my personal collection of books, I’ve been asked if I lend my books to friends.” He looked at me. “Yes, I do. But do my friends return my books? No, they don’t.”

“I don’t intend to borrow any books from your personal library. Because I too may not return your books.” I smiled under his searching gaze. He led me to the door, and I gently climbed down the stairs. As I got to the bottom, he waved to me from the door. “Don’t forget to mention in your article that I love India. And that I’d love to return to your country.”

I lost contact with Mr. Forster for the next two months. I was deeply absorbed doing a couple of assignments for my supervisor. But I did keep thinking of my last meeting with Mr. Forster. I was eager to see him again on the pretext of doing another interview. The gracious person that he was, I knew he’d accommodate me again. Surprisingly enough, one day I saw a note signed by him lying in my mail box at my college, Fitzwilliam House. It read, “Can you come over for tea next Saturday? Same time, 4.30 afternoon. I want to discuss with you a book I’ve just read, Nirad C. Chaudhuri’s Autobiography of An Unknown Indian.”

I’d skimmed through the book. But when I got the letter, I walked over to Heffer’s bookstore to pick up a copy. I browsed it randomly. It was an atrocious tirade against India and its people. The Times had put out a rare review of the book, and The Illustrated News rated it the best book published in England in the last three decades.

However, all Indian students at Cambridge felt deeply hurt by this betrayal of his own country by an Indian who just wanted to pick up a sumptuous royalty abroad. The book was simultaneously published in the USA, and it was scheduled to appear in translation in different European languages.

We’d a hurried meeting at the Cambridge Majlis where we discussed how to counter the negative impact of this book on the British leadership. An Indian scholar, Gopal Swamy, shot off a letter to the Editor of The London Times, but the paper did not take notice of it. Similar was the response to the letters sent to other British papers. Like my fellow Indians, I was disillusioned.

I looked forward to meeting E.M. Forster over the weekend for I was eager to know his reaction to Nirad C.

Chaudhuri’s book. I’d hardly entered King’s College when I was overtaken by a heavy downpour. I had to run across the lawn to reach Forster’s rooms. As I climbed up the steps, I noticed that his front door was half-open. A gentle knock at the door, and I was greeted by his genial voice coming from inside, “Come in, Mr. Kumar.”

E.M. Forster gestured to me to sit in the chair I’d used the last time we met. The logwood fire spread heat and warmth, and on the coffee table next to me stood a bottle of wine with two glasses.

“Why don’t you try some wine this time, instead of tea?”, Forster asked, smiling. “It’s vegetarian stuff,” he added.

I understood that he wanted to save himself the inconvenience of fixing tea or coffee for me. So I responded, “Let me try it, may be for the first time.”

As we both sat sipping the sparkling wine, he opened up. Picking up a copy of Nirad C. Chaudhuri’s book from the side table, he looked at me.

“I think it’s a marvelous piece of writing. Don’t you agree with me?”

At once it came to me that he’d fallen for it. I couldn’t help saying to myself that Forster was no different from any other Englishman. The book had obviously pleased him, satiating his desire to read something that idealised British culture, and denigrated Indian tradition and heritage.

The rain had started to batter the window panes with a drumming sound made me come out candidly without any reservation.

“I beg to differ, Sir. I honestly feel it is a horrific piece of writing — almost blasphemous.”

My statement made him sit up, face glowing with a tinge of petulance.

“You have a right to your opinion, Mr. Kumar, and I understand your

feelings. Don’t forget that I love India, but we should take a book for what it is. I repeat that it is an outstanding piece of work, regardless of its harshness towards Indian sentiments.”

I responded, “Sir, before I explain my reaction to the book, let me say that I happen to know the author personally. He was my colleague at the All India Radio, where he was Talks Officer, with his office next to my room. I used to have tea with him almost every day, and we used to engage in long conversations. Nirad is a dwarfish man, not more than four feet two inches who tries to appear larger than life. He would always come to office dressed in a three-piece suit, a hat on his head and neatly polished suede shoes. Most of my colleagues used to call him a bore, because he'd often pull out a bunch of photographs of his children. I remember how he once took out a photograph of his son, Dhruv. ‘This is my son who is now eighteen. Even when he was five, he enjoyed listening to Beethoven's Sixth Symphony. And he could enumerate all the elements in the solar system. When he grew up to be sixteen, he began to play the piano, and his favourite music was Western. He could talk about British painters, musicians and philosophers.’”

At this point, I paused for a while as I’d almost run out of breath. Pulling myself together, I continued, ‘let me at this point say that I don’t agree with T.S. Eliot when he says, ‘Honest criticism should confine itself to a work of art, not the man behind it.” No, I won't buy that statement because I earnestly believe that the man behind a book is as important, if not more than his work. Let me here add that if Macaulay had been alive today, he would have adopted Nirad as his dream child. I assume you'd recall Macaulay's historic minute of 1838 which said that ‘By imposing English upon Indians, we’d rear up a crop of Indians who would be Indian in colour but British in thought and temperament.’ So here is a typical child of the British colonial dream.”

I paused for a moment. “But I haven’t explained to you Nirad’s real motivation in writing this book. Indeed, he’s a man of encyclopedic breadth of knowledge, and he handles the English language with superb skill and confidence. I once asked him, as executive officer at All India Radio, to write a talk on Panini. Instantly he asked me, ‘Which Panini? There are two Paninis, one the grammarian and the other the sage. So which one do you want me to write on? I was indeed amazed by this man's learning. Mildly I said, ‘let it be Panini, the sage’. On another day, I requested him to write an article on Indian birds. The very next day, he brought a six-page piece on all kinds of birds. But in spite of his skill at writing and his versatility, he was ignored by his principals at All India Radio. For several years, he held the same position, with no promotion or increment. It made him feel he’d been brushed aside by the establishment as non-entity. He wanted to rocket into fame by writing this book, and bring himself into the limelight — an ‘unknown’ Indian now too well-known. Since he’d been ignored by his Indian friends and bosses, he decided to take shelter in British culture and tradition. To him, the Englishman and the British empire were his pedestal on which rested all his loyalty and dedication. No wonder, his Autobiography of An Unknown Indian was dedicated to the British Empire. The venomous things he’d to say against India! Permit me to read out from the book a paragraph.”

I understood that Mr. Forster did not interrupt me in the seemingly interminable stream of words because he was a very courteous Englishman. I also divined that Mr. Forster was more with Nirad, than with me.

“I beg your pardon again, Mr. Forster, for blabbering away. But being a sensitive Indian, I had to open out my heart to a gracious person like you.

Forster smiled. “Mr. Kumar, you say you’ve come here to do your doctorate. I feel you should take to writing instead. Your graphic description of Nirad C. Chaudhuri sounded like an interesting character portrayal in a novel.”

I acknowledged his compliment with a gentle nod. “Sir, let me share with you a dream I’ve nourished since my childhood. I’ve always wanted to be a writer, primarily a poet. Only secondly a novelist. So I seek your blessings to become a good writer in the coming years.”

Forster changed position in his chair. “Certainly, I’ll look forward to your first book of poems or your first novel, if I’m still around at that time. Don’t forget that age is catching up for me. I don’t know how much time is left.”

“A hundred years to you, Mr. Forster — that’s what our holy scriptures say is the ripe age to close one’s eyes.”

Forster got back to Nirad C. Chaudhuri’s book. “After what you’ve said about Nirad C. Chaudhuri I’ll have to give his book another read. Maybe, we will get to have a chat about it.” Our conversation drifted through diverse subjects.

When I got up to leave, he came with me to the front door to say goodbye. “Mr. Kumar, let’s meet again. And please remember, I don’t want Nirad C. Chaudhuri to come between you and me.”As I stepped out into the Quadrangle, I wondered if I’d succeeded in presenting Nirad C. Chaudhuri with his Indophobic views in the right perspective. I remembered Forster’s statement in an essay in his book Two Cheers For Democracy: “If I were to choose between betraying my country and betraying my friend, I hope I’d have the guts to betray my country.” I wished him to deny Nirad C. Chaudhuri for me and my country.

Four months later, I felt I could invite E.M. Forster to the annual meeting of the Majlis which had elected me as its President. My gift of the gab, and my ability to sing ghazals and recite poems got me the post. When I mentioned this to Forster, he congratulated me.

I also informed my father about my election as President of the Indian Majlis. He wrote back a very warm letter expressing his happiness for me. He wrote, to quote from the letter, “I’m particularly gratified on your election. It is an achievement to be proud of. I remember reading in Jawaharlal Nehru's autobiography that he was elected as vice-president of the same association. This is only the beginning of a glorious career for you.”

During my Presidentship, the Majlis received a message from the Indian High Commission in London that Sir Sarvapalli Radhakrishnan wishes to visit Cambridge, and adequate arrangements should be made to take him round the campus. I took it as an opportunity to spend some time with someone who was not only Vice-President of India, but also a renowned philosopher and thinker for whom I'd great respect and admiration. I responded to the direction from the Indian High Commission by offering to personally take him on a sight -seeing tour of the university. Excitedly I waited for a word about his arrival at Cambridge. I was asked to meet him at University Arms, a centrally situated hotel. I walked him down to Trinity College, where I showed him Newton’s Clock. I gave the names of the celebrities who had studied at Trinity: Charles Darwin, Thackeray, Lord Byron, etc. I also mentioned to him that Jawaharlal Nehru was a Trinity alumnus who had preferred to live in comfortable lodgings far away from the college.

Radhakrishnan said, “Well, I can understand that his father, Pandit Motilal Nehru, would have liked his son to live like a prince. Like a member of the British Royalty.” After Trinity, we visited my college, Fitzwilliam House, which was only a few yards away. It faced the great Fitzwilliam Museum on the other side of the street. I told him that I'd taken the liberty of fixing up a meeting with my master, John Thatcher. I explained to him why Mr. Thatcher was very keen to meet him. It was because he had served as professor of philosophy at Agra college, Agra. He’d also read most of Radhakrishan’s works, and that he had found Kalki and The Hindu View of Life fascinating to read. When he heard this, his face began to glow with pride.

I escorted him up the steps to a small room where Mr. Thatcher was waiting for us. A centre table was loaded with all kinds of eats, cakes, pastries, almonds and cashew nuts. There also stood on the table a tea kettle covered with a woolen cozy. After tea, when we came down the steps, I asked my esteemed guest, “I hope, Sir, you liked meeting my Master.”

“Indeed,” he said slowly, “A nice man.” He paused for a brief moment as if searching for words. “But he has an ugly face. I noticed a scar on his left cheek.”

I was shocked. Was my honoured guest interested only in meeting good looking people? If handsome is what handsome does, Mr. Thatcher was a beautiful personality. Was Mahatma Gandhi a handsome person, I asked myself.

So disillusioned I was with what he had said that I decided to cut short the sightseeing trip with him. Almost brusquely I said, “Well, sir, this is all that Cambridge has to offer. I hope you enjoyed your brief visit to my university.” Saying this, I walked him back to the University Arms.

That night sleep did not come easily. I asked myself why there was such. a vast chasm between precept and practice, and between appearance and reality. I found it difficult to digest the unpleasant experience I’d with Sir Radhakrishnan. So I decided to share it with my mentor, E. M. Forster. I left a note with the security guard at King’s asking for an appointment the next afternoon. Next morning, I got the communication that he’d be pleased to meet me again.

When we met, we didn’t talk about Nirad C. Chaudhuri, only Sir Radhakrishnan. Mr. Forster too had reservations about the esteemed guest from India. “Do you know, I never thought much of him as a philosopher.”

I then told him about another Indian personage who had disappointed me like Nirad C. Chaudhuri and Sir Radhakrishnan. “I’ll tell you about my experience with Pandit Ravi Shankar, the sitar maestro. You are interested in music, so you must have heard of him.” I remembered Ravi Shankar because he had been my colleague at All India Radio from 1948 to 1949. If Nirad C. Chaudhuri had his room to my left, Ravi Shankar had his office to my right. A wooden signboard outside his office announced him as Music Producer. Since we shared a love of music, I used to meet him quite often. During our conversations, he would blow his own trumpet, like Nirad C. Chaudhuri, about his creative talent. He’d tell me about the new ragas he’d created for All India Radio.

During my stay at Cambridge, I learnt that he’d resigned from All India Radio and had become something of a travelling performer. He gave concerts in London, New York and Paris. An year later, when I went to attend a seminar in Santiago, I learnt that Ravi Shankar was staying there. I wanted to revive my association with him that went back to our stint at All India Radio. To my great disappointment, when I telephoned Ravi Shankar, someone from his family came on the line: “Of course, Pandit Ravi Shankar remembers you. But he regrets he cannot spare any time for you.”

It was another disillusionment about human beings that came to me in Santiago. Back at Cambridge, I got absorbed in my research, though I took time out for the Majlis. As President of the Majlis, I decided to invite E.M. Forster to our Diwali celebrations. He readily accepted my invitation. He said he would be delighted to revive memories of the festival of lights he had enjoyed when he was in the Dewas State. With the approach of Diwali, I made the arrangements for a banquet and cultural programmes. A variety of Indian sweet dishes were ordered. On Diwali evening, I took personal care to have candles lit both outside and inside the Taj restaurant which we used as a venue for our public functions. While my friends lit the candles inside the central hall, I stepped out to have the candles lit all along the pavement facing Trinity. Passersby stopped to watch. An elderly Englishman walked up to me to wish “Happy Diwali.”

I invited him, “Thank you, Sir, and please join in our festivities.”

“My dear young man, I’d love to but I’ve an appointment.” He looked at his watch. “I must move on.” A few minutes later, an octogenarian English lady stopped in front of the hotel. She stared at the signboard outside the Taj Restaurant.

“A nice name,” she said. “You know, I’ve been to the Taj in Agra. The mausoleum raised in marble by the Emperor Shah Jahan in memory of his beloved wife, Mumtaz Mahal, is an immortal symbol of pure love.” I felt like telling her that it was not pure love, but lust. The Moghul Emperor let his wife bleed through thirteen pregnancies till she died in childbirth. Another hiatus between illusion and reality. I held myself back, because Diwali is not the time to say anything unkind about anyone. “Yes, ma’am, the Taj will always be looked upon as an enduring symbol of love.” I smiled at her. “Won’t you come in to taste some Indian sweets?”

“Oh, I’d love to! What do you’ve inside? Rasgullas, Jalebis, Burtis and papadams?'

“Everything for you, ma’am. Just walk in. We’ll be honoured to have you as our guest.”

It was time to start the Diwali celebrations. The crowd had gathered inside the restaurant. But I still waited outside to receive E.M. Forster, our chief guest. When he appeared round the comer, I was bowled over to see him dressed in a sherwani, with Jaipur shoes on his feet.

“You look an Indian prince, Sir,” I complimented him.

Forster gently inclined his head in acceptance of the compliment. “Thank you. I wanted to look like one of you, especially on a great occasion like this.” I led him inside to his chair on the dais. Next to him was a chair for me as President of the Majlis. The first item on the programme was a scene from the love episode between Jawaharlal and Edwina Mountbatten. I’d identified an Indian friend of mine who bore a close resemblance to Nehru. He appeared in a Nehru jacket, a rose in his third buttonhole and a Nehru cap on his head. On the other side of the table sat an English young lady who was to act as Edwina. The entire audience was thrilled to see the couple. Edwina opened up, saying, “Very painful to feel that we’d be leaving India tomorrow. Will it be the end of our love affair?”

“It was never an affair,” mumbled Jawaharlal Nehru. “My love for you will remain eternal till the snows on the Himalayas melt away and the Ganges dries up.”

“Beautiful!,” she sighed. “You know, darling, Louis could never say such a beautiful thing.”

“Well, husbands tend to take certain emotions for granted. I’ve always looked upon Louis as a gentleman.”

“That’s a gentleman speaking. That’s my Jawahar, my lover poet, not the Prime Minister of India. I also never came to you as the wife of the first Governor-General.”

Smiling, she quipped, “I know, Jawahar, it was you who held him back in India as the first Governor-General of the free republic, otherwise, both of us would have been packed off just a day after you got your Independence.”

As the scene ended, Forster turned to me to ask, “Who wrote this piece?” Crimsoning, I responded, “I wrote it.”

“So I wasn't wrong when I said the other day that you had in you the making of a writer — a poet or a novelist.”

The audience applauded with the clapping of hands. A voice came from the gathering asking me to recite a ghazal. Instantly, I recited a love ghazal from Mirza Ghalib in which the poet accepts his beloved as his goddess, and assigns to god a secondary place.

Programme over, I decided to escort Forster to the street’s end.

I fancied that, someday, in my late sixties, I’d return to my alma mater, enter the gates of King’s, walk past E.M. Forster’s rooms, lie on the bank of the Cam, watch the clouds’ reflection in its placid waters, and dream away.