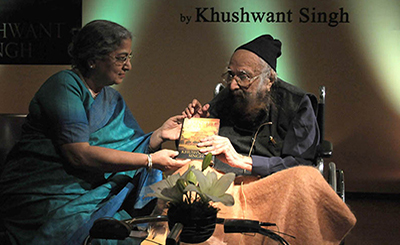

Sabyn Javeri in New Delhi recently. Photo: Shireen Quadri

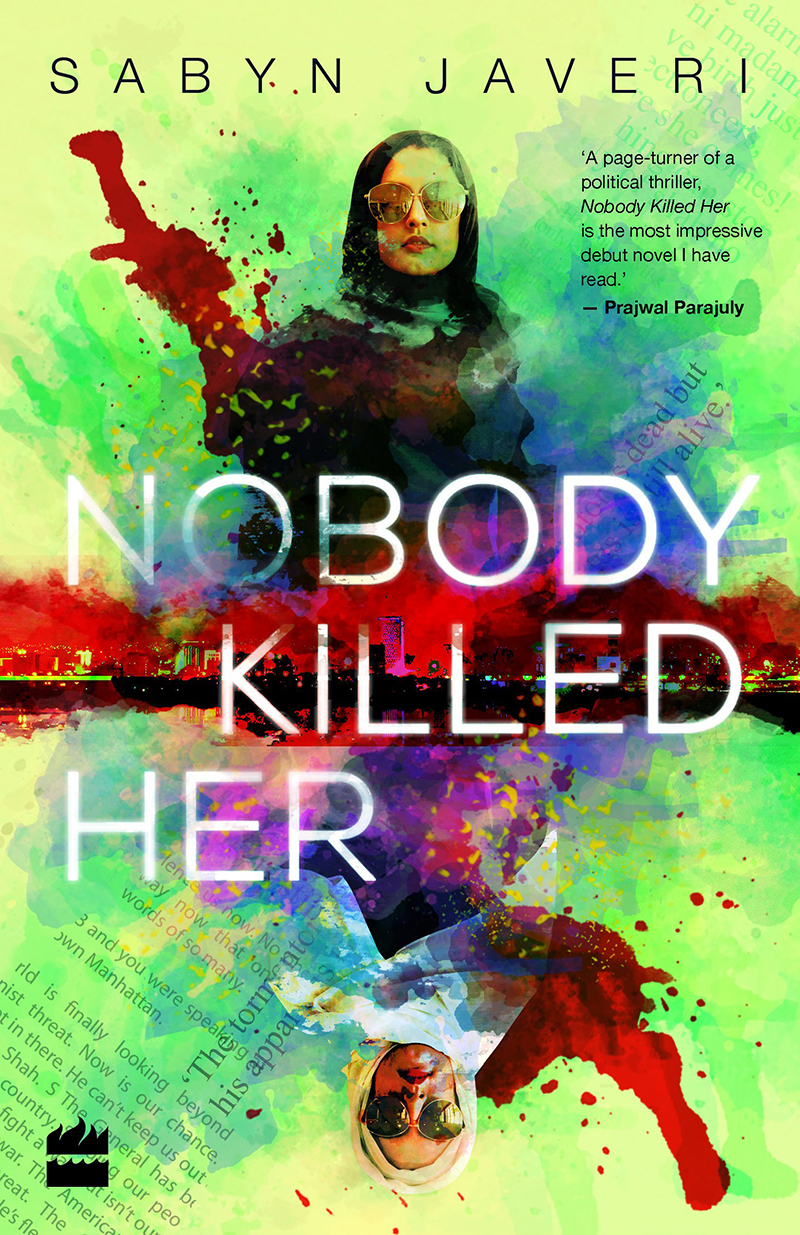

Sabyn Javeri’s racy debut novel, Nobody Killed Her (HarperCollins India, 2017), is the story of friendship between two women — Rani Shah, the Prime Minister who is assassinated, and her close confidante, Nazneen Khan or Nazo, who is suspected to have a hand in Shah’s assassination as she escapes the bomb blast unscathed.

The novel, which blends noir with courtroom drama, delves into issues like love, loyalty, obsession and deception. While political intrigue and machinations are at the heart of the novel, it also delves into patriarchy and fanaticism that the country is steeped in.

Javeri was born in Pakistan and now lives between London and Karachi, where she teaches Creative Writing at the university level. Having written short stories earlier, she has received the Oxonion Review Short Story Award and was shortlisted for the first Tibor Jones Award.

For Rani Shah, Javeri drew upon the rise to power of many women leaders in South Asia, like, Benazir Bhutto, Indira Gandhi, Sheikh Hasina and Aung San Suu Kyi. “If I had focused on just one individual, it would have been a biography. But I was not interested in that. I was interested in cherry-picking the elements which made their journey all the more tumultuous, all the more interesting, all the more problematic. And, therefore, all the more celebratory,” says Javeri, who was in India recently. Excerpts from an interview:

THE PUNCH: Nobody Killed Her deals with a wide gamut of issues. While class is at its heart, there is also the issue of gender, especially in south Asian context. You have talked about in interviews that you modeled Rani Shah not just on Benazir Bhutto but many other women, like Leila Khaled, Indira Gandhi, Sheikh Hasina and Aung San Suu Kyi. Tell us about your interest in such figures? Did you want it to be a blend of noir and courtroom drama?

SABYN JAVERI: I chose the structure — cold facts of the transcript vs the internal monologue, narration of a character — as the idea of history vs memory is interesting to me. History is said to be very objective because it’s collective. Memory is supposed to be personal because it’s individualistic. And, if you take the example of Partition, the history that you are going to read is going to be very formative and if you speak to individuals, it’s going to be very different. It’s going to be memories of friendships left behind, of nostalgia, of love for the land, of missing friends, and relatives behind or families separated. It’s going to be very intimate. So, that really interested me. I studied about these women leaders when I was researching for my doctorate. What was their story, their trajectory and the history that got them together? How did they rise to power and how did they hold on to it? If I had focused on just one individual, it would have been a biography. But I was not interested in that. I was interested in cherry-picking those elements which made their journey all the more tumultuous, all the more interesting, all the more problematic. And, therefore, all the more celebratory. So I took all those elements. I also wanted to look at women leaders not just in politics, but in other arenas — that’s were Leila Khaled, the liberator or freedom fighter as people like to address her, comes in. The rise to power is not always straightforward. It may appear so in newspapers or in history books, but the interpretation behind that is what interested me more. Therefore, I settled on its two-part structure — the factual one and the interpretation of facts.

THE PUNCH: By interspersing the narrative with Nazo’s own narration, you give her a chance to tell her story in her own voice, perhaps different from what cold facts would state. Was this important to you?

SABYN JAVERI: It’s quite interesting as a lot of people feel that it’s Rani Shah’s story. For me, it’s Nazo’s story. It’s about perception and not about what actually happened because in the end it’s all very personal, very subjective. Every individual sees the same event differently and that’s what triggered the technique of the unreliable narrator. I wanted the reader to get involved. I wanted the reader to draw their own conclusion.

THE PUNCH: You were also interested in creating an antagonist, an anti-heroine?

SABYN JAVERI: Yes, definitely. I’m very interested in breaking stereotypes. I love pushing boundaries. I think that’s because I don’t have a very high opinion of myself. There are some women writers who take themselves way too seriously. They want to become the representatives of their gender, of their country. I think as an artist one should experiment with craft, with art, with voices. In the end, what matters is that you put out something that’s entertaining, affirmative and also touching.

THE PUNCH: So, from the very beginning, was it clear to you that it was going to be a thriller? While the intrigue involved is political, on some levels, it is also about the ambition and the desire of a particular class to belong to another class. Interestingly, towards the end, you hint that Nazo Khan has begun to resemble Rani Shah.

SABYN JAVERI: That was from Margaret Thatcher because she, towards the end of her career, had begun to speak like the Queen. She started thinking of herself as the Queen. She started speaking like her and almost stated thinking of herself as the Queen. I found that very interesting and used it in the novel. It was very conscious because I wrote something before this. It was very literary, very beautiful. Unfortunately, nobody wanted to publish it as it didn’t have a story. So, I went back to the drawing board and did it very scientifically. A lot of writers think it’s formulaic. I don’t think it’s a formula because it’s not like one size fits all. In Pakistan, many journalists asked me about my qualification and authority to write a political thriller. That’s when I realised that I never thought of myself as a woman. There is a lot of sentiment about it and not everyone has been happy or accommodating, but the youngsters in Pakistan have been very receptive. They have really come out and supported it.

Page

Donate Now

Comments

*Comments will be moderated