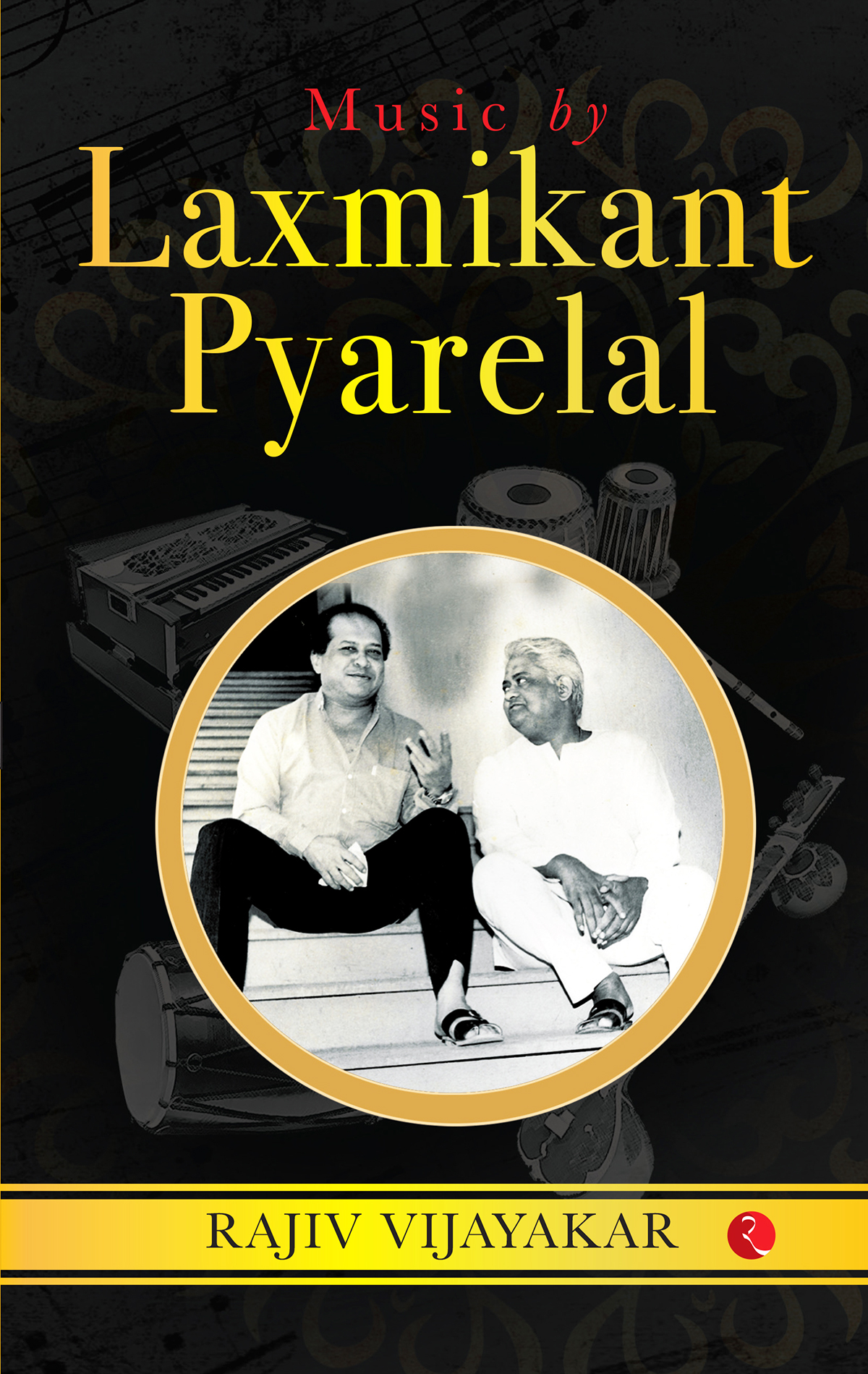

Laxmikant Shantaram Kudalkar and Pyarelal Ramprasad Sharma. Photo: laxmikantpyarelal.com

‘In my house, the radio was always on, as dad was a film music lover, and so were my three brothers and I. I was 11 or 12, and was witness to the transition when Laxmikant-Pyarelal overtook Shankar-Jaikishan. I was a huge S-J fan, and loved the music of Sangam, but Dosti brought in a tremendous amount of freshness and I could feel the difference from the S-J, O.P. Nayyar era. The new duo was doing small-budget B-grade movies, but in them, their music would always be the A-grade highlight.

In my college days, their scores like Aaye Din Bahaar Ke, Shagird and Mere Hamdam Mere Dost were my favourites and had an amazing aura and atmosphere in their orchestration.

Till the early 1980s, I had no opportunity to meet them, though they had recorded some songs with my brother Manhar, including Hero. I had seen them at functions but never been formally introduced to them.

It was in 1984 that director Ravi Tandon called me up and said that he was making Jawaab, an interesting subject around a ghazal singer, and he wanted me to sing for it. I had recorded a film song for Usha Khanna in 1971, but never again, as I was somehow cut off from cinema. In any case, I was so busy that I never needed film songs for my livelihood either, so I was hesitant. But Ravi ji said, ‘We will create a hungama (sensation)!’

And so I met Laxmi-ji for the first time: we were to become very close later. I noticed that Laxmi-ji had kept my first song ready: “Mitwa Re Mitwa”. There were musicians with a tabla, dholak and guitar, and he had a longish tape recorder with piano keys. He also had a harmonium in front of him, but he did not play it like other composers did, but just kept one finger on Sa (the first note) and one on Pa (the fifth note) and sang the whole song. I was amazed at how well he was singing, with perfect murqis. He sang twice, and I sang with him the third time, and we rehearsed again at the recording.

I was quite upset that Pyare-bhai was not there — he was unwell and had written the score and sent it across. His brother Gorakh bhai was conducting the score. It was a small orchestra as the song, within the film, was sung by Raj Babbar at a mehfil. After a few days, I was again called for what was a proper ghazal written by (Anand) Bakshi saab, “Sabak Jisko Wafaa Ka Yaad Hoga”. Laxmi-ji’s instructions were to sing it as if I was singing on a show.

His brief was, ‘Khulke apne andaz mein gaaiye, alaap lijiye, yeh sur hai, yeh raag hai (Sing it freely in your style. Use alaaps. This is the scale and this is the raag.). I dare say that this remains one of my better-sung film songs, and Universal Music, which marketed that film’s music, would o%en put it into compilation albums of mine that they would issue until CDs were being made.

Some months later, I got a call from Rajendra Kumar, who was relaunching his son Kumar Gaurav in a film called Naam. Mahesh Bhatt was coming out of hibernation and Salim Khan was writing independently for the first time after his split with his partner. I was riding a wave of popularity, and Rajendra Kumarji told me, “You have to act in my film!”

I was taken aback, as acting was not my area. I told him I will let him know in a couple of days. I was sure I did not want to act, so I avoided calling him. Some days later, my elder brother Manhar Udhas, who Rajendra ji knew very well (he had sung for him too) called and asked me why I was being so disrespectful to the star. I explained my situation, but he told me that I should at least have the courtesy of calling the actor up to tell him I could not take up his offer.

I realized my mistake and called Rajendra Kumar saab. I told him that acting wasn’t my domain at all, as I was a singer. And he burst out laughing!

“I did not explain what I wanted properly, so it’s not your fault at all,” he told me. “I just want you to sing a song that will be filmed on you. And you will be enacting the song on stage as yourself — Pankaj Udhas! You know, if I had wanted an actor, I had many options.”

I told him that in that case, I would be more than happy to do his movie, as I had grown up on his films. At the first sitting, Rajendra Kumar ji, Bakshi saab, Salim saab and Bhatt saab were also there, and they were discussing the situation in the film— where Sanjay Dutt attends my live show abroad, and is moved enough by my song to decide to return home to India and family.

At that point, the sitting was over. And at the next sitting, I was seated adjacent to Bakshi ji, and he suddenly said,

“Haan bhai Laxmikant, likho… (Okay, Laxmikant, write this…)”

And he recited the now-cult words,

Chitthi aayi hai aayi hai chitthi aayi hai

Chitthi aayi hai watan se chitthi aayi hai

(A letter has arrived back home)

Just as I was wondering that the words were too simple for what was planned as a ghazal, came Bakshi ji’s masterstroke that left me thunderstruck! He went on,

Bade dinon ke baad hum bewatano ko yaad

Watan ki mitti aayi hai

(After a long while, this letter has brought us a whiff of

our nation’s soil to us emigrants)

Laxmi-ji placed his hands on the harmonium as always, thinking for a few minutes, and the next thing was that he sang the whole mukhda without a pause. I could not believe it. He had just read the mukhda once or twice, and it was such a lilting tune; the unanimous reaction was that it was an awesome mukhda!

Bakshi ji always wrote in the Urdu script, and I could read the language. The briefing continued, and Rajendra Kumar ji told him that he was to try and bring in all our major festivals like Baisakhi, Holi and Diwali for which families always come together, and anyone not present is remembered.

I saw Bakshi ji write the words Holi, jholi, goli, Diwali, and was again stunned when his final lines came in:

Tere bin jab aayi Diwali

Deep nahin, dil jale hai khaali

Tere bin jab aaye Holi

Pichhkari se chhooti goli

(When Diwali came,

it was my heart that was burning, not the lamps

And at Holi,

my water-gun seemed to fire bullets)

Now these are really precious moments to cherish, when I found that I was working with people who were true-blue geniuses.

Laxmikant was born to be a composer: some moments on his harmonium, and a perennial song was out! There was no effort to compose. Everything came spontaneously, with or without the lyrics written! The song was a long one, and I had a couple more sittings with Laxmi-ji to memorize the song and its nuances, and finally I learnt it by heart.

At the last sitting, there was this young boy, so young that his moustache was just coming out, and Laxmi-ji said that he was a brilliant singer, who had left his family in Punjab to come and struggle in Mumbai. He told me, “Let us see his reaction to the song.”

As I began to sing, the boy slowly started sobbing, and by the time I finished, he was crying, clearly engulfed in his own memories of his family and hometown. Laxmi-ji asked him, “Tu gaayega? (Will you sing?)” The boy nodded.

At the recording, my brother Manhar had come, and so had, in a rare case, Laxmi-ji’s wife Jaya bhabhi. Laxmi-ji had so much patience with any singer. If needed, he would sing a song 20 times and never tire. And it would be sung in exactly the same way, with the harkats coming at exactly the same points!

I had rehearsed a lot, but after three takes, Laxmi-ji’s combination of a sixth sense and tremendous experience led

him to come and sit next to me. He told me that I was singing superbly, but the something extra that was there in the rehearsals was not coming out. He ordered tea for us and reminded me of “Sabak Jisko Wafaa Ka Yaad Hoga”. He said, “I want that kind of a mood, of a live concert.”

In the singer’s cabin, I had to stand while singing, so he asked me, “In your shows, how do you sing?”

I said that I would normally sit with my harmonium in front of me.

“Just give me five minutes,” he replied and dashed off.

Would you believe it? In the big musicians’ hall, he arranged for some tables on which a carpet was placed to make a makeshift stage, and he made me sit on it with a harmonium! They placed a microphone there and the new sound balance took about 30 minutes. And when he said, “Take karte hain (Let’s record)”, I sang the long song without a single mistake!

After it was over, he came over and smilingly said, “Aapne kamaal gaaya. (You sang wonderfully.) It was 100 per cent better than at the rehearsals!”

(I was later told that he did the same thing with Pt Rajan and Sajan Misra during the recordings of their songs in Sur-Sangam so that they felt comfortable.)

I had not heard the full rehearsal by the chorus, but at the end of the take, from the chorus, a high-pitched voice sang the lines, “Bade dinon ke baad hum bewatano ko yaad, watan ki mitti aayi hai”, which went on Akash Khurana in the film as he comes to embrace me on stage. And when I asked Laxmi-ji who the singer was, he said, “Remember the boy who started crying? It was him. His name is Sukhwinder Singh.”

Yes, “Chitthi Aayi Hai” was Sukhwinder Singh’s first recording! And the song, which is now always played at all of my concerts, was special to me also because I met Pyare-ji for the first time! And just look at how the two stalwarts created the interplay of harmonies and interludes for my next song with them, “Aaj Phir Tumpe Pyaara Aya Hai” with Anuradha ji in Dayavan.

My last song for them, after “Meri Zindagi Mohabbat” for Mohabbat Ki Aag (which did not release, I think) was the hit

“Woh Ladki Jab Ghar Se Nikalti Hai” (Tejaswini), for which he worked with my favourite lyricist Mumtaz Rashid, because, even as late as in 1996, Laxmi-ji wanted a fresh kind of verse. For him, life was always a king-size celebration!’

Excerpted from Music By Laxmikant Pyarelal: The Incredibly Melodious Journey by Rajiv Vijayakar (Rs. 595, pp 344), with permission from Rupa Publications

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated