Jerry Pinto: Photo courtesy of the publisher

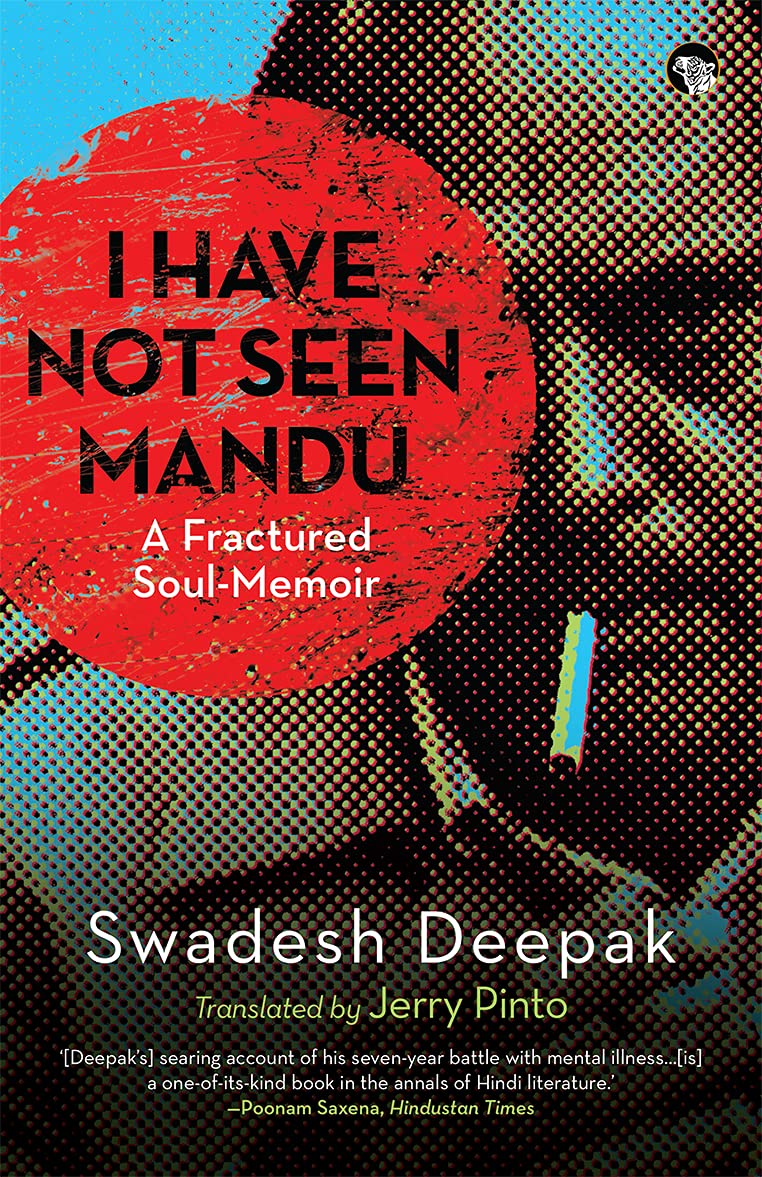

The author of Em and the Big Hoom (Aleph) on translating Swadesh Deepak’s memoir, I Have Not Seen Mandu (Speaking Tiger Books)

You have done translations previously as well, but this time you were translating from Hindi. What kind of research went into it and how was it different from when you translate texts from Marathi? How challenging was it to keep the form of the text, with fragmented sentences and fluid timelines, intact in translation?

I believe that Swadesh Deepak wrote his memoir as an act of faith. Or as several small acts of faith which went into the magazine Kathadesh. He had an old faith in his readers who, he said, in a dedication to one of his short story collections, had kept the faith through the seven years he spent — the silence of exile.

One of the interesting things about reading I Have Not Seen Mandu was this leapfrogging through time and space. It was dizzying but I kept saying to myself, ‘Your discomfort is nothing compared to the discomfort Deepak went through when he was in the hospital. And even in recovery, to go back and excavate memory cannot have been easy.’

I believe that tidying up the text would do it a disservice of the worst kind because it would prioritise the reader's comfort over the gravamen of the text.

You said about Em and the Big Hoom that it was 90 percent fiction and 90 percent fact. While translating I Have Not Seen Mandu, did you have to consciously try to not let your own experiences affect the core of what Swadesh Deepak had written? In that sense, how mechanical is the exercise of translation?

There is nothing mechanical about the ways in which I read or write or edit or translate. Reading is what I do to feed my soul. And so it is integral to my sense of self. At one time, as a freelance journalist, I wrote to order and in some ways that was not the way I wanted to write. I wanted to be free to experience language and tell the stories that had been haunting me. By the grace of God, I can do that now. To translate offers the witchery and magic of the intersection of two or more languages. (Deepak’s book uses Hindustani, Urdu, Punjabi and English.) But go back a step. How does one choose what one wants to translate? That depends on what one reads. How does one choose what one reads? That is a loaded question and any honest answer must take in reading as a private act and pit it against the new mediated reading where your TBR is a public document. But suffice it to say that what one reads is also a personal choice.

But I take it that you mean that I have had a deep and personal encounter with a different mind. Perhaps it was that which drew me to Swadesh Deepak’s magnificent book. Perhaps it was that which allowed me to take the risk of translating it.

Reading I Have Not Seen Mandu was a pretty overwhelming experience for me, as a translator you would have had to read the text innumerable times. How did you find yourself dealing with it emotionally and psychologically?

I heard about the book when Sukant Deepak wrote a piece about his father in A Book of Light: When A Loved One Has a Different Mind, a book I edited for Speaking Tiger. I noted the name and promised myself that I would get around to it at some point. At the time I was helping Shirin Sabavala sort out Jehangir’s papers to send them off to the Museum. And there was a copy of I Have Not Seen Mandu. It carried a Sabavala painting on the cover. I borrowed it and on the bus home, I began to read it and fell into the book. By the time I got home I was hooked. I knew that this book had to be translated and I suggested to Sukant that he should do it. He said it was too personal and without thinking I said, Then may I do it? He agreed and I was in.

Speaking Tiger has a rigorous editing process so I kept having to go back. At the time of the edit, I was also helping a friend write an account of her brother’s suicide and the effect it had on her and her family. Needless to say, that was a dark time.

In the introduction, you write that it’s impossible to tell if the misogyny and the communal streak he displays are a part of his character or a manifestation of his mental state. Do you think anyone living with mental illness, and in this case a writer, is deserving of empathy sans any judgement? Can the act of reading ever be removed from our inherent tendency to judge and to classify in order to put ourselves at immediate ease?

I have no easy answers to your nuanced question. I have said that reading for me is an intensely personal thing and so I must allow that it should be intensely personal for everyone else as well. Thus if a reader puts down I Have Not Seen Mandu because of the misogyny of its voice, that must be her/his choice.

And yes, we make judgements. It is a human thing to do. Even choosing to read Book X and not Book Y involves a judgement call.

Swadesh Deepak writes “Society brands the mentally ill”, he laments that there’s little awareness and sensitivity towards mental illness in our country. Do you think this scenario has changed for the better since the memoir was published originally, especially with the increasing advocacy of mental health awareness on social media in recent times?

There have been many changes since the time Swadesh Deepak wrote his book. But I still believe we have miles to go before we come to a place where we can claim that mental ill health attracts no stigma. And this work has to be done at the macro level with more space in hospitals for psychiatric wards, better laws to protect the rights of the ill, the provision of mental ill health leave, more medication made available at subsidized rates in public hospitals and all that; and there must be work done at the personal level. We need to check ourselves for prejudice.

In the introduction, you say that this is a book about writing. Did the experience of translating it made you stop and mull over your own writing practice or inform it in some inevitable way?

All language is a patchwork quilt, made out of history, stuffed with borrowed feathers that were on finer birds, stained with use, familiar and unfamiliar at the same time.

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated