Goa remains an ambiguous concept, still forming and reforming into a whole which writers of Goan origins are striving to understand

Goan literature is that of the outlier, the febrile imagination of the peripheral. For more than two centuries, Catholic Goans have given expression to their fictive dreams in languages which were non-native to the Indian subcontinent. Firstly in Portuguese and then in English. When in 1864, Luis Manuel Julio Gonçalves founded the Ilustração Goana, an influential journal of its time, carrying much of his own output, it gave rise to a flourishing of literary endeavour within Goa. The quantum of literature produced by Goan writers writing in Portuguese has remained unacknowledged within the Indian literary canon. Not only was Portuguese alien and inaccessible to much of the Indian-subcontinent, but the style of Goan storytelling was heavily influenced by Eurocentric literary traditions and interpreted through an essentialism unique to our own colonial experience.

Cielo G. Festino of Paulista University, Brazil, an academic and scholar of world literatures, writes: ‘One of the symbols of Portuguese culture on Indian soil was the Great House, the Casa Grande, which represented the power of the Portuguese colonizers, who left Goa in 1961 after the territory was annexed to India. These houses have been described by Caroline Ifeka as “stately Catholic mansions ruled by landed aristocrats whose sensibilities [were] oriented to the West, rather than to the East” and whose division into “unchanging and physically bounded sub-units of interior space” pointed to cultural values that permeated not only the architecture of the house but also the highly stratified Goan Catholic society—’ (Stories from Outside and Inside the Goan Casa Grande, Postcolonial Texts).

Goan literature then remained rooted in the ancestral house from which central characters of power emerged often pitted against the disenfranchised. There was the bhatkar (the landlord, the landed gentry, benevolent or otherwise) who occupied prime position, as patriarch of the family and often of the village, whose machinations effected the lives of those around him, usually the mundkars (tenants). Whatever the space in these narratives occupied by ‘little lives,’ Goan literature remained exclusionary, for ‘little lives’ were imagined into existence by the idle classes, wealthy enough to follow literary pursuits. ‘Little lives’ were not voicing their own stories, they had no agency or opportunity to do so, their stories were being told by the same power-nexus of land, Portugal and patronship which created a Eurocentric elite in Goa, and which largely reinforced the dominance of the landed classes.

The first rupture to this literature of the casa grande emerged in Bombay. By the mid-19th century, a substantial migration of Goan working class populations made their way into British India, namely Bombay. A spontaneous upwelling of a working class zeitgeist in this satellite community gave rise to a seminal form of theatre which came to be known as tiatr. Influenced by Italian opera but rendered in Konkani, it countered the privilege of Portuguese-centric narratives. Within the church halls of Bombay, Goans flocked to live performances of song, dance and plays, which savaged the Goan elite, often through comedic performances.

Concurrently, a new consciousness was emerging in Bombay amongst elite Goan students at Grant Medical College or at St. Xavier’s, which was vehemently nationalist, anti-clerical, and with an awareness of societal disparities. A certain noblesse oblige made them assume responsibility for this obvious inequality, and seek redressal. These sentiments found their way into contemporaneous literature, articulated in the writings of Telo Mascarenhas, the poetry of Armando Menezes, the novel, Sorrowing Lies My Land by Lambert Mascarenhas. A generation later, Victor Rangel-Ribeiro’s award-winning novel, Tivolem, explored the imbalance of class and gender.

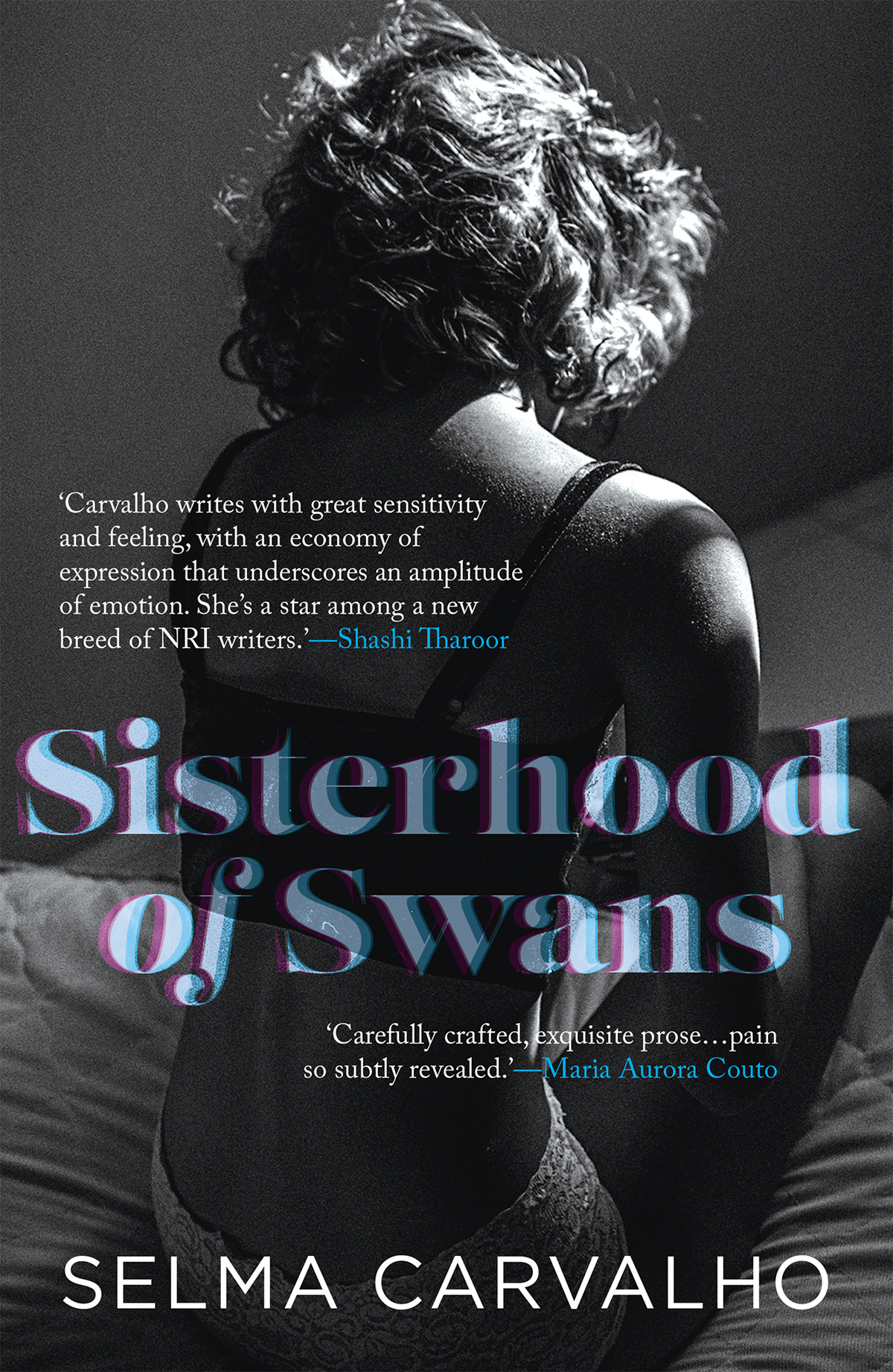

In my newly released book, Sisterhood of Swans (Speaking Tiger, 2021), I have wrenched my Goan characters from their parochial villages and Bombay gymkhanas and hoisted them firmly in London.

How does one reconcile regionality with universality? For a state as tiny as Goa rooted in its own profound sense of nationhood and identity, it is almost an impossible task to overcome the specificity of geography. Perhaps, then, a new modernity could only be birthed in the diaspora. An alternative understanding of Goan lives could only be drawn in fiction if the possibility exists for characters to find themselves conflicted by entirely new moral ambiguities. Although, the self-exiled writer, writing from the diaspora is another feature peculiar to Goan writing, the quoin of characterisation and plot of their writing was still rooted in Goa, in the idea of home or a return to ‘homelands,’ unspooling stories anchored in Goan villages, lives interconnected by a historical past.

In 2016, Roanna Gonsalves, based in Australia, took her protagonists out of Goa and the Goan enclaves of Bombay, and situated them in Australia, in her award-winning collection of short stories titled The Permanent Resident. In my newly released book Sisterhood of Swans (Speaking Tiger, 2021), I have wrenched my Goan characters from their parochial villages and Bombay gymkhanas and hoisted them firmly in London. My protagonist, Anna-Marie Souza, a second-generation Goan immigrant inhabits a world enriched by diversity of race, a world of cultural revolutions and counter-revolutions, a world of collapsing identities and a search for their reconstitution. And yet her conflicted self is instantly recognisable to readers from Delhi to Dallas, for beyond our individual selves, is a universal world of shared grief and pain. In Sisterhood of Swans, I explore the promiscuous body with its open wounds, vulnerable to sexual power dynamics still largely favouring men. Inevitably, Anna-Marie finds herself to be a single parent failed by the very men who should have assumed responsibility. As she spirals into despair, acknowledging her loss of agency, she muses: I think about things then, and the transient nature of their lives, how momentary ownership of them does not imbue them with value; how their value is decided only by our need and willingness to possess them, and how vulnerable they are to abandonment.

There’s always been a pressing question as to what constitutes ‘Goan literature.’ Is it limited to Goan writers residing in Goa, is it literature influenced by the social and cultural mores of Goa, can we include Goan writers writing from the diaspora, can we include non-native writers writing about issues pertinent to Goa? Perhaps Goa itself remains an ambiguous concept, still forming and reforming into a whole which we are striving to understand. But as writers of Goan origin reconfigure the boundaries of our literary traditions, as we leave behind the casa grande, the parochial village, the church square, class and caste equations, our characters are going to find themselves in increasingly complex moral quandaries, asking questions about the new world they inhabit and their place in it.

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated