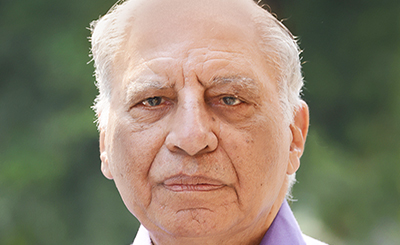

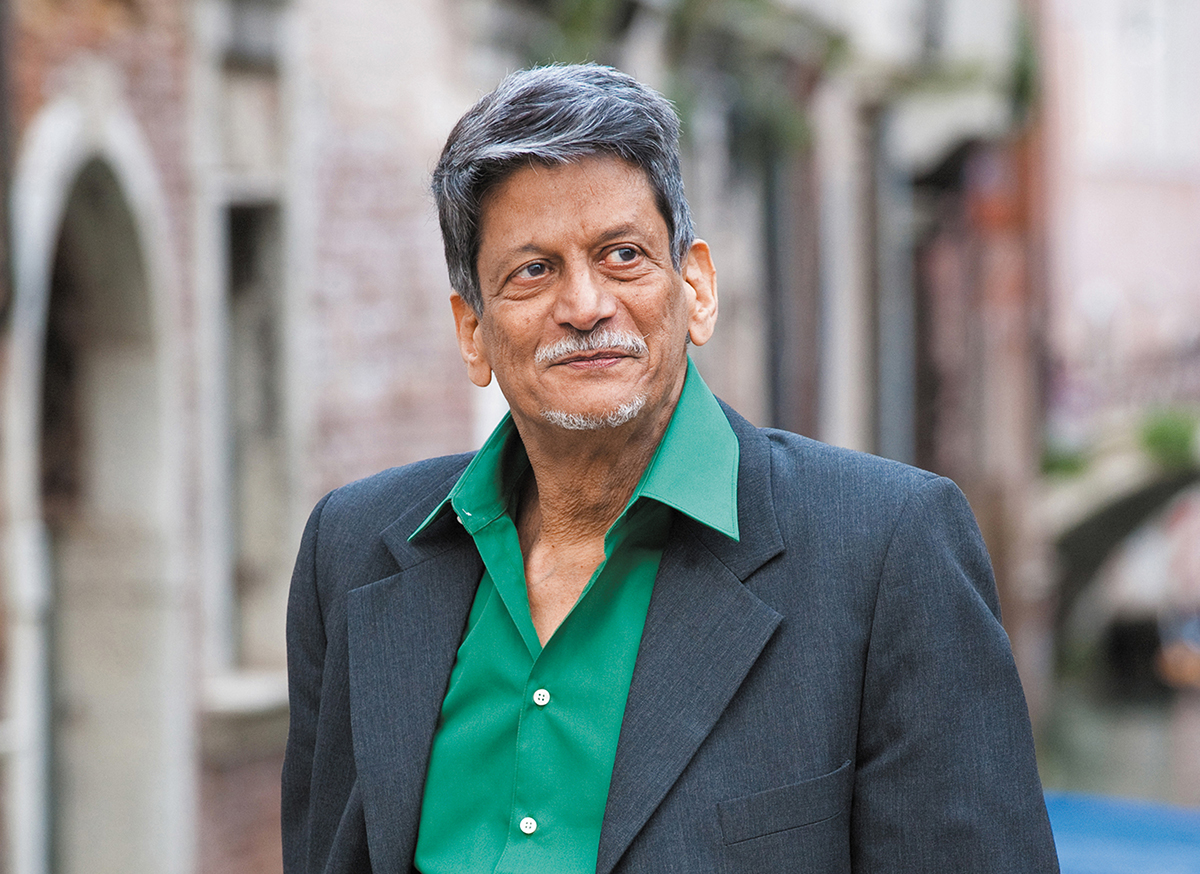

Kiran Nagarkar. Photo courtesy: Marco Secchi

Armed with disarming, sellf-deprecating humour, Kiran Nagarkar looks at the world through a glass lightly. The novelist, playwright and critic endears you to him with his insouciance, with his ability to laugh at himself.

I owe Nagarkar a huge debt. He changed my pre-conditioned, saturated-with-Victorian-literature mind and filled it up with unabashed appreciation of humour in Indian writing in English. He did that with Ravan and Eddie (1994), an uproarious romp through a chawl in Mumbai.

Born in Mumbai in 1942, Nagarkar is one of the most significant writers of postcolonial India. His works include Saat Sakkam Trechalis (the 1974 Marathi novel recently translated as Seven Sixes Are Forty Three, Ravan and Eddie and the epic novel, Cuckold (1997) for which he was awarded the 2001 Sahitya Akademi Award in English. He has explored humour in all its forms — wit, sarcasm and satire.

Nagarkar has been hailed as a “must-read” author of modern Indian writing in English and his influence and popularity are witnessed both in India and abroad. He recently launched his new novel Jasoda. A “lazy” writer, in his own words, Nagarkar brings Jasoda to the world after 20 years. For two decades, the character has dwelt in the recesses of his mind. Finally, she has seen the light of day. On the eve of the novel’s launch, we got up, close and personal with Nagarkar, who continues to add pillars to the bridge called Indian writing in English.

Prepping up for the interview, I placed my recorder next to Nagarkar. He asked me, “Do you want to come closer? I mean not you, the recorder. Do you want to move it closer?” We laughed at this, and I was glad our tete-a-tete began with laughter.

“These days I am terrified of saying anything,” he began. “We are no longer a country with humour. And I really miss it, very, very badly. I hope to God you are going to joke with me and tell me what an ass I am. That would be perfectly fine!”

The interview lasted for well over an hour and not for a minute did the conversation falter. Nagarkar didn’t shirk a single question nor was he impatient for the interview to end. He spoke with as much ease and humour about his books as he did about other things. He was as comfortable speaking his mind, choosing his words and brandishing his sense of humour at his companion’s house on Breach Candy as he was at the Women Writers Fest where I met him later. As he would have preferred it, he was there for his book Jasoda. Organised by SheThePeople, the festival had women writers discussing various genres. As he stepped onto the podium, Nagarkar joked, “I have had a sex change operation and now here I am at the Women Writers Festival.”

Apart from wanting to hear him talk about his work, I attended the fest to hear him read from the book. Which he did! He chose to read a goosebump-inducing page where he has described Jasoda at childbirth, all alone and very brave. She delivers her second child by herself in the open, after having tilled the barren land with her emaciated bullock. Her elder son is trying to suckle even as the new born slides out of her onto the ground. Before the bullock is finished licking the placenta off, Jasoda has smothered the newborn between her thighs. It was after all, a girl!

At 75, Nagarkar doesn’t wear glasses. He doesn’t need to. It will do us good to view the world with his spectacle-less, un-myopic eyes. Only then can we find in it humour and substance, something worth living with, something worth dying for!

Excerpts from the interview:

Kanishka Ramchandani: When did you realise that humour is no longer welcome in our country?

Kiran Nagarkar: It has been so especially since the new regime. I am talking about humour because I believe that humour is a very serious business. For instance, when humour is sharp, it makes you think. It makes you say, 'Oh my God, what is Swift saying!' when Jonathan Swift writes things like ‘why don't we eat our children’ in his essay ‘The Modest Proposal.’ Something must have been radically wrong for him to suggest such a thing. Look at the condition of children here! An 11-year-old girl dies and she catches the people’s attention. What about the hundreds of children who die every day?

For me there’s humour, the kind that Arun Kolatkar, the poet, used to indulge in. He was a serious sort of person but when he was in the mood, he would enact Laurel and Hardy as well as Charlie Chaplin. And as I have no self-control, I would be rolling on the floor with laughter. I love that kind of humour. When I was writing Ravan and Eddie, the only two children I have ever had, I gave them a lot of funny adventures. Ravan doesn't know whether he is really Ram or Ravan. Now that's something each one of us has to ask ourselves all the time. I certainly had to ask myself this question. I feel impossibly guilty of the fact that an 11-year-old died in my city. I know I am enlarging the picture but that's how it is.

Once in a while you hear our Prime Minister talk about unity. And yet he doesn't say a word about people who murder girls or about Dalits. Luckily or unluckily, one of my earliest books was a play — Bedtime Story. It wasn't published for 38 years. It was published in 2016 for the first time. It was not allowed to be performed... went through tremendous censorship problems. But I have the character of Eklavya in it who is a tribal. The premise came from the fact that we reject the tribals as we do the Dalits. What havoc have we played with the tribals? Why would they not rebel?

Can we think of what we would do if we were tribals or Dalits? I am not defending any kind of violence but would we allow more oppression to be done to us? You treat people so humiliatingly, you make them starve, you rape their women and then you complain that they are rebelling. If possible, take a look at Bedtime Stories, and you will understand what I am trying to say here. It hit me recently that while I had written it, I had not really understood that Eklavya is perhaps India’s one and only self-made person. Growing up, I always had the impression that the ideal relationship between a guru and a shishya is the one between Eklavya and Dronacharya. When I look back I feel 'was I off my rockers?' How can we reiterate this relationship as an iconic one?

I know I have digressed a lot but I feel that in Bedtime Story, in spite of the grim things happening, there is still humour. I don't know what I would do without it.

Kanishka Ramchandani: What kind of humour can we find in Jasoda?

Kiran Nagarkar: Jasoda is a grim tale, it’s very stark! It's also really black. But that is the fate that we have consigned to the extremely poor. I am talking about women. We have done this to poor women and it just shows what men are about. Women have not got back and said to the men — how dare you do this?

Jasoda is all about possibilities. First of all, it's a story. When I am writing a novel, I don't want to sound as if I'm preaching or make my novel a public forum. But the point of stories, as we have seen in our epics, is that they leave some residue behind, which begins to ferment over the years. That's why today we are thinking about Sita and Eklavya. At this late age of mine, I have realised that the Mahabharata was far more honest than most of us are.

To get back to your question, yes, there is humour in Jasoda. I hope to God there is humour! And there are quiet moments also. There's a young girl in Jasoda who speaks her mind, which often gives rise to humour. In this novel, I have attempted to bring the temperature down because what is happening is inflammable as it is. You know how husbands behave. Amongst the poorer sections of the society, husbands come and go. A man has children with his wife, then moves on to another woman, and then goes back to his wife to live off her. He is a drunkard, jobless and a wastrel. And that's perfectly acceptable. We see such instances everywhere, be it Mumbai or remote corners of Bihar.

Kanishka Ramchandani: When was Jasoda born in your head?

Kiran Nagarkar: Right after Cuckold was published in 1997. I must have written the first 70 pages then. Jasoda is very different from my other works. I have never really delved so deep within poverty, absolute poverty.

Kanishka Ramchandani: Do you regard Jasoda as a modern Indian heroine?

Kiran Nagarkar: I do, I do! When you read the novel, don't forget she's not virgin snow. She has inherited what the menfolk have given her. But I won't blame her for that. Don't forget that this woman of whom I think so highly, if her son would want to get married, I won't be surprised if she does to her daughter-in-law what mothers-in-law and sons usually tend to do.

Kanishka Ramchandani: Are there any parallels between Jasoda and Odysseus?

Kiran Nagarkar: Not really! I grant that there’s one episode in Odysseus’ tale that is relevant here. During one of his travels, Odysseus docks his ship outside a kingdom. The king invites him to his court as a royal guest. Odysseus leaves the court with bags full of gifts from the king. He returns to his ship, stows the bags away in his rooms and goes off to sleep. His faithful and reliable deputy gets annoyed by Odysseus’ attitude of never sharing anything. He decides to rebel and opens the bags. The King had packed treacherous winds in the bags, which are let out once the bags are opened. The travellers are not able to return home for months. This is what intrigues me about mythology. The deputy was wrong about rebelling, but how could Odysseus not share anything with them? Apart from such multiple layers, I don't think there are any other parallels between Jasoda and Odysseus.

Kanishka Ramchandani: What was the most challenging aspect of having a woman as the central figure of the novel?

Kiran Nagarkar: Women have always played a major role in my novels. For instance, both Ravan’s and Eddie’s mothers are strong characters. Regarding Jasoda, I would like to repeat that when your husband is that debased and is not going to do a damn thing, then your options are exactly zero. And yet with zero options, you continue to improvise to be able to provide for your children. She may have bumped off her daughters but she has to raise her boys. It was similar with Ravan — his father was perpetually in bed, and Eddie’s father dies because of a fall. I have been told often that these two women (their mothers) have been, in their own ways, heroic.

And then there’s my heroine in Cuckold. If anybody has taught me a few lessons, it was the Little Saint, whom I didn't care for. She is an absolutely independent woman! The Maharaj Kumar wants to bump her off but he ends up falling in love with her. So, way before all the talk about feminism came up, there was this woman who simply claimed — I am my own woman. In that sense, there's a running theme when it comes to women in my novels.

Kanishka Ramchandani: Are there any similarities between Jasoda and the mythological Yashoda?

Kiran Nagarkar: No. Jasoda is also a surrogate mother to her neighbour's child but the surrogacy is of a different kind and the similarity, if any, ends there. Yashoda is a remarkable woman, to have taken up none other than Lord Krishna. If the reader finds her echo in Jasoda, they are welcome to it. I love such echoes. Yashoda’s priceless quality is that the boy she is raising is not her son and not for a moment does she let him realise this.

Our mythology has so many impressions of motherhood. Why is Krishna always depicted as blue? Because the demon Putana has breast-fed him. Our epics call her Krishna’s foster mother. Our mythology highlighted the idea that once you have fed a child, you become a mother figure, even if the milk you fed was poisoned.

Kanishka Ramchandani: Of all your novels, which was the most difficult to write?

Kiran Nagarkar: I am a terrible writer! And there’s no excusing the fact that I take a century to write a novel. I have never met anybody as lazy as I am. But I feel God's Little Soldier was a difficult book. It came after Cuckold. For some reason, Cuckold is considered by many as one of the finest novels written in world literature; although I have never taken any credit for that. I have no problem in saying this because with Cuckold I was the clerk who did the writing. I had a difficult hero in Cuckold — he sends his soldiers to their deaths, he plans to kill his wife because she refuses to sleep with him. And yet many of my readers thought of him as a very fine human being. So I was extremely worked up about the fact that after Cuckold, I had to deal with a protagonist who is very bright and cares intensely for things but who is at heart a terrorist. However, it's not a novel about terrorism. It's a novel about extremism. No matter which faith Zia follows, he ends up taking extreme positions. At one point in the novel, he is a Trappist priest. When I was at the Trappist monastery, they used to bury people without a coffin, and after a few years, the remains are put with those of other people. Because they realised that death is just a passing phase. In Zia's case, when he realises what orphans go through, he wants to do something about it. Zero orphans are his ambition. But even there he takes a totally extremist stand.

I was asked to teach my novels at a university. A few female students stopped coming to my class because Zia was so anti-feminist. Zia is a character in the book, he's not me. They somehow started identifying him with me. It was exactly the same with Cuckold. They had no sympathy with Maharaj Kumar, who on his wedding night discovers that his wife is in love with someone else. Those ladies were completely anti-Maharaj Kumar.

Kanishka Ramchandani: How do you tackle writer's block?

Kiran Nagarkar: I don't tackle it, I contribute towards it. I take up every small excuse not to write. For instance, I kept saying to myself that I need to do some work but now you are here and I can happily not work. There’s a Marathi writer I used to know who said, ‘Words flow from my fingers.' Now whether I should have cut her fingers or her throat off, I don't know (laughs).

Kanishka Ramchandani: You wrote Ravan and Eddie in Marathi first...

Kiran Nagarkar: First 70 pages... then I stopped. With my novel Seven Sixes Are Forty Three and my play Bedtime Story, I took criticism very badly. Now Seven Sixes… has been declared as a classic but back then all I got were 'joote'. I was a fool to take it seriously. Take a look at it — it's very visual and doesn't have a linear structure. In 1967, it was a complete departure from the norm. And then I wrote Bedtime Story, started just before the Emergency began and finished it when it was over. In fairness to my two gurus and other well-wishers, Seven Sixes… was an absolute landmark and I had no reason to be discouraged from writing in Marathi. But I took it all seriously. I don't know, I just gave it up.

Kanishka Ramchandani: Do you want to go back to writing in Marathi?

Kiran Nagarkar: If I was not so damned old and lazy, I could have gone back.

Kanishka Ramchandani: What are you more comfortable writing — novel or play?

Kiran Nagarkar: Novel!

Kanishka Ramchandani: Wikipedia describes you as an important post-colonial novelist. Do you agree with this? How much of post-colonial thought do you consciously put into your work?

Kiran Nagarkar: These terms come and go. There was a whole bank of critics who used to do post-colonial studies. So long as you are not hindered by these terms! Very simply put, I am a storyteller.

I was born before Independence. I was quite young then but watching the flag hoisting and putting up a tricolour on my window are things that have stayed with me. While completing my masters, I met writers who had re-discovered their mother tongue and were studying it to be able to write in it. I love the languages I know — Marathi, English and Hindi. But this urge to go looking for languages was never present in me. When I used to write short stories initially, my writing had a colonial slant. I am grateful that I started writing in Marathi for the simple reason that there were no Westernised names. For instance, a female character in my story was called Chandani. In English, it would have become Chandni, but Chandani referred to sandalwood and Marathi helped me retain this beauty.

Kanishka Ramchandani: How do you go about researching for your novels?

Kiran Nagarkar: My rule is very simple. I am a storyteller and my research will always be hand-in-glove with imagination. Many novelists in our country suffer from what I call 'researchitis.' For them, research takes precedence. That's not how I work.

In case of Cuckold, I got everything right in a peculiar way. Without knowing what I was up to, my companion got me Baburnama. I didn't realise that Babur would play such a major role in my book. My friend Arun got me a Hindi edition of Meerabai. When I started writing, I decided I can't have these two names there. It's just too much baggage.

Kanishka Ramchandani: Who have been some of your early influences?

Kiran Nagarkar: Coleridge had said that you have to be a stone not to be influenced. I gratefully admit that I have been influenced by a great many people. Arun was one of the finest poets our country had. When I was with him, people thought 'Kiran is in good company.' Graham Greene is one of the novelists that I admire. Other authors like the French writer Louis-Ferdinand Céline and the Italian writer Curzio Malaparte have influenced me. But I will not be able to pinpoint the exact places where their influence is visible. Somewhere, you have to find your own pathway. And then there were two of my professors who had a great influence on me. They were beyond brilliant. Today, they are not around for me to pay them back. Actually, I don't want to pay them back. Why should I make them lose their humanity by doing that?

Kanishka Ramchandani: What about your family?

Kiran Nagarkar: I owe my English language schooling to my father, who put me in an English-medium school after class four. I'm genuinely grateful for that. And yes, poverty must have also influenced me.

Kanishka Ramchandani: Do you plan to write your biography?

Kiran Nagarkar: I hope I have the sense not to! But I don't know for sure.

Kanishka Ramchandani: What do you do when you are not writing?

Kiran Nagarkar: I used to have a passion for movies. At the International Film Festival, I used to watch 6-7 movies a day. But for the past 5-6 years, I haven't seen a damn thing on the screen, except news.

Kanishka Ramchandani: Are you on social media?

Kiran Nagarkar: Nahi, nahi, woh toh bilkul nahi hai. Mere se nahi hoga! (No, no, I am not at all savvy. I can't do that!). If possible, I would like my work to be there. I would like people on the social media to read my work. I can't be on social media myself but I can even touch their feet to make them read. I am shameless that way! Otherwise why write?

Kanishka Ramchandani: You have been part of a literature festival (Tata Literature Live) where you received the Lifetime Achievement Award. What relationship should an author forge with festivals?

Kiran Nagarkar: It’s my perpetual belief that it’s not about the authors, it’s about their work. One doesn't need to talk about the authors except in the context of the book. Tata Lit Live has many panels, I don't have a problem with that as long as there is solid discussion happening. But I strongly feel that the discussion should be about an individual book. Another aspect is that there are some festivals where one “ought” to be seen. Now, how that has come about is beyond me. One of the great qualities of the Tata Lit Fest is that the film folks are not involved in it by and large. So many literary festivals have a component of films and by films I mean Bollywood. Films already have an audience; we need to cultivate readers of books through these festivals.

Kanishka Ramchandani: But I must say your book reading sessions are very entertaining. You had come to my college once and read excerpts from Ravan and Eddie and it was great fun.

Kiran Nagarkar: Oh! God bless you! I wish I was God and could tell you now — jo mangna hai maang lo! (Ask whatever you wish for!)

Kanishka Ramchandani: How do you see literary awards?

Kiran Nagarkar: So long as they give me every one of them, it’s fine! Kisi aur ko mat dena (Don't give them to anyone else). Since you are interviewing me, I am sure you are very well-connected. Please put in a word for me at the Nobel committee.

Kanishka Ramchandani: What are you reading these days?

Kiran Nagarkar: I take a few years to finish a couple of pages of a book. I am reading Humayun just now. And before that I was reading The Untitled by Gayathri Prabhu.

Kanishka Ramchandani: How did life change for you after Ravan and Eddie?

Kiran Nagarkar: After Ravan and Eddie, I was getting noticed. But life changed in a very, very limited sense. Given that the Indian audience numbers in crores, I really don't think they understand humour. One would assume that humour sells. But if your humour is not value-based, then it's good for a laugh but in the long run, it is more damaging than influencing. For instance, the subject of chawls can offer a lot of humour but ultimately the chawl can't be looked at as something funny. You have to understand that the chawl was the brainchild of the British, the colonisers. Don't you want to give the people who stay there light, air and space and, most importantly, respect? You pack them in those tiny dark airless pigeonholes! Therefore, I feel humour has to be primarily value-based, because if it's not, then it is pointless.

I was very happy with Ravan and Eddie, really liked the cover. The falling boy remained a theme throughout the trilogy. For me, Extras is an important book as it's a true reflection of what this city is. Whether you are poor, middle-class or extremely rich, there is only one fact of life — Bollywood. There's only one place that's far, far worse than Mumbai, the South. There the devotion towards films is quite different. There film stars are gods — you don't bathe anybody else with milk. When MGR died, people committed suicide. They have a temple for Amitabh Bachchan in Kolkata. When you go back, you should tell the people at The Punch Magazine that they should build a temple for Kiran!

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated