Vaddey Ratner. Photo courtesy of the author

Vaddey Ratner, a survivor of the Khmer Rouge regime in Cambodia and author of two novels, on her attempts to uncover the beauty and dignity in the desire for life

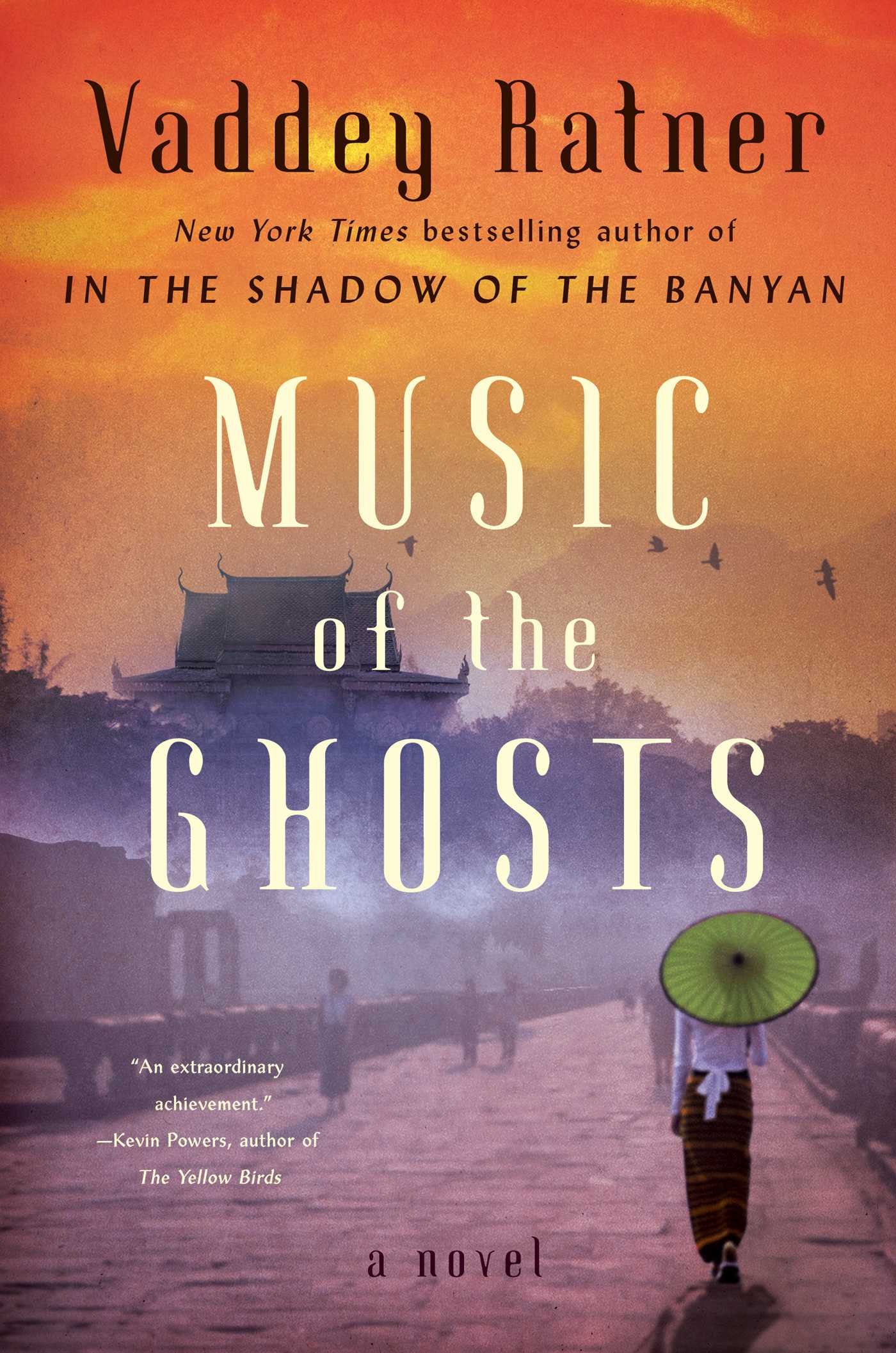

Vaddey Ratner, a survivor of the Khmer Rouge regime in Cambodia, is the author of two novels. Her critically-acclaimed debut novel, In the Shadow of the Banyan, was published by Simon & Schuster in 2013. A New York Times bestseller, it was selected as a finalist for both the 2013 PEN/Hemingway Award and the 2013 Indies Choice Book of the Year. It has been translated into 17 languages. Her second novel, Music of the Ghosts, was published by Simon & Schuster in April this year.

“If my first novel, In The Shadow of The Banyan, is a story of survival, Music of the Ghosts, is a story of survivors,” writes Ratner in her note to the second novel.

Ratner was five years old when the Khmer Rouge came to power in 1975. After four years, having endured forced labor, starvation, and near execution, she and her mother escaped while her father, aunts and cousins perished. In 1981, she arrived in rural Missouri as a refugee not knowing English, and later, living in the low-income Torre de San Miguel housing project in Saint Paul, Minnesota, graduated as her 1990 high school class valedictorian. A summa cum laude graduate of Cornell University, she specialized in Southeast Asian history and literature.

Ratner is a descendant of King Sisowath, who ruled Cambodia in the early part of the 20th century. In 1970, her father’s first cousin, Prince Sisowath Sirik Matak, led the coup that ended monarchal reign to establish a short-lived republic, soon engulfed in the chaos of the broader Vietnam War.

Ratner says that as a writer, her role is not simply to shine a light on tragedy. “I feel it’s much more difficult — and more necessary — to portray how people who know suffering recover the ability to see goodness,” she says.

Excerpts from an interview:

The Punch: Let us begin with In The Shadow of The Banyan. While writing it was an act of honouring the dead, a redemptive act to bring to memory members of your family whom you lost during the genocide unleashed by the Khmer Rouge between 1975-1979, what also makes this novel remarkable is its tremendous empathy, its absolute lack of anger at the perpetrators of heinous crimes. In the years that you were working on the novel, as you struggled to revisit the memory of the barbarity and the horrors of those days, how was this process for you? Was there at all any anger or resentment? Did you consciously not let it creep into the narrative?

Vaddey Ratner: Anger is akin to reflex. Empathy stems from a deeper reflection. It can require years, decades, even a lifetime of cultivation. As a child going through that experience, there was fire in me. I wanted so much to lash out against the brutality, the insanity, the senselessness I witnessed and endured. But if I’d done that, it would have brought my own death, or worse, the death of those I loved — both the remaining family and the friends and neighbors who’d helped us.

So, as a young child, I was forced to ask, what use is anger? What purpose will it serve? By the time I’d decided I would write this story, as a teen when I’d begun to grasp the English language, or later as an adult when I began to work with the aim of transforming it into fiction, I’d embarked on a search to understand, to look deeply. If you enter into such a process with anger, you cannot hope to understand.

Once I’d succeeded in exhuming the ghosts, I felt that to harbor anger would be wrong. As much as I suffered, I survived — and that survival is a gift. When I am among the ghosts, what right do I have to anger? They suffered the absolute consequence of brutality. My duty, among the living, is to ensure that those lost are not forgotten. And you can’t do that with anger.

The Punch: How important was it for you to mould it all into a story of hope and perseverance? So, while there is ordeal and suffering, the characters, especially the protagonist, 7-year-old Raami, is also someone who’s looking for redemption at the end, someone who’s invested in the idea of a better future. How important was it for you to highlight that greater human values ultimately survive? So, even when the novel is replete with death and destruction, there are stuff like dreams, stories and poems as the novel’s leitmotifs.

Vaddey Ratner: What I find curious in Western culture today, especially in contemporary fiction, is the tendency to see hope and beauty as less complex than despair and disillusion, as if the latter are necessarily more nuanced or sophisticated. In the US today, people speak of the danger of blind optimism. I suppose in certain privileged circles, people can choose to stay walled off from much of the suffering and discontent around them. That’s dangerous because it distorts your perspective. But in a place like Cambodia, where you confront suffering at every corner, where you find children living off garbage dumps, and musicians maimed and disfigured by land mines, there is no space for blind optimism. Amidst such continual suffering, hope becomes very complex.

As a writer, my role is not simply to shine a light on tragedy. I feel it’s much more difficult — and more necessary — to portray how people who know suffering recover the ability to see goodness. Under such circumstances, hope is not blind or without tension. It’s a struggle as well. Every day, people who live in great suffering, who have every justification to give up, choose instead to persevere. For me, the only possible foundation for art is to live in awareness of such suffering while endeavoring to uncover the beauty and dignity in the desire for life. Hope, perseverance, redemption… these are more than literary tropes. For me, they are the very foundation of existence.

The Punch: In the tragedy that unfolded until 1979 (the year the Khmer Rouge’s reign ended), you were also to lose your toddler sister and many of your extended family. You and your mother were lucky to escape and arrived in the United States as refugees. Could you talk about that phase a bit? What sense could you make of what was happening around you? What were your first impressions of arriving in the US?

Vaddey Ratner: On arriving in the US, I was in awe. We had emerged from hell. At the refugee camp on the Thai border, we saw locals nearby who had their own homes, land to farm, and the freedom to move around. Their lives were at least familiar, if not within reach. But coming to America, I felt I had arrived in a place that was not of this Earth, that existed on a different plane altogether. We called it “the third realm,” and it was beyond anything I could have imagined.

Yet, with time, I’d come to learn that America is full of people like myself, people who escaped atrocities, people who carry the burden of great suffering, if not in their own lives then in the lives of their ancestors. I learned of the sustained violence against native Americans, the enduring consequences of slavery, the plight of waves of immigrants and refugees from Europe and Asia and Latin America. I came to appreciate, not just in the history books but also in the examples of people I met, the strength of those who endured and built and redefined this country. This fed my own strength, and my sense of possibility that I too could find a place, and find a voice.

The Punch: You were so traumatised by the atrocities and the tragedy that you had become mute. Do you see the novel as symbolic of you finding your voice?

Vaddey Ratner: Definitely — but the notion of recovery is more than symbolic.

During those first few years in America, I regained my ability to speak, and soon my facility with English surpassed my mother’s. I was very conscious that she was a woman so eloquent in our native tongue, and yet, every time she stepped out of our home she became someone — a refugee, an outsider — who spoke only broken English. In such moments, our life seemed as broken as the language we adopted. I wanted so desperately to find a way for the scattered pieces of ourselves to coalesce into something whole and new — a world as beautiful as the one my mother had built for me before the war. I wanted to capture that beauty and gift it back to her.

When In the Shadow of the Banyan came out, witnessing my mother’s reaction after she’d read it, I felt that I had succeeded in that task. In the years since, I’ve heard from fellow Cambodians who describe a similar response to the novel — the feeling of seeing their beloved homeland come to life again, in the fullness of its tragedy and its beauty. There’s something restorative about that.

Recovering my voice is a personal journey, but in exercising that voice as a writer, I find that I am not alone. I write in a realm shrouded in near silence — our collective inability as Cambodians to talk about the trauma of genocide. Because of this, it’s all the more affirming as I hear other voices echoing in response to say, Yes, we were more than that tragedy. Cambodia was more than the killing fields. Once, it was home.

Page

Donate Now

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated