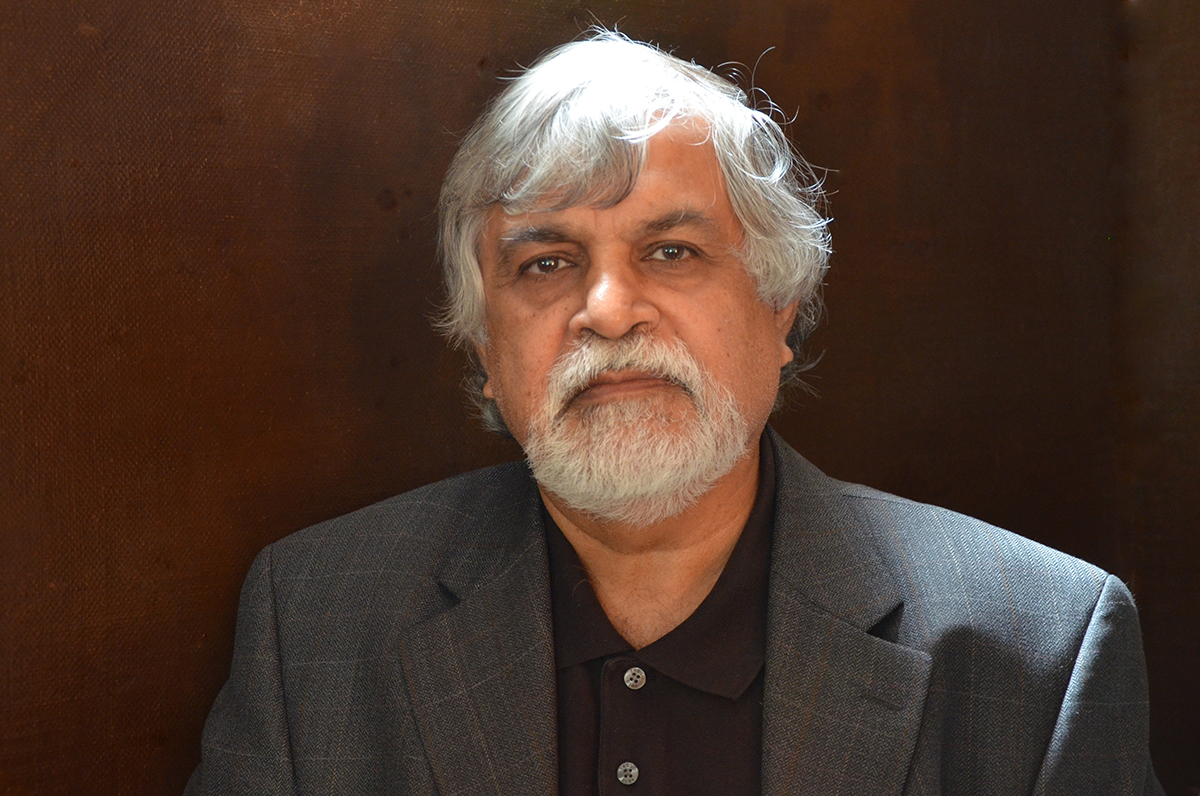

M. G. Vassanji. Photo courtesy: Penguin Random House India

M. G. Vassanji on history, memory and identity in his new novel, Nostalgia

In his new novel, Nostalgia (Penguin Random House, 2017), M.G. Vassanji, who explores the whorls of memory in his memoirs and novels, takes us into an indeterminate future in Toronto where people, in their quest for immortality, can live lives of two or three “generations”. Whenever the time feels right, a person can transition into the next generation.

The personal history of the current time becomes irretrievable, replaced by an ideal life story of choice: a neatly concocted fiction which aids in constant rejuvenation. But one day, a strange-looking man — Presley Smith—arrives in the office of Dr Frank Sina, presenting symptoms of Leaked Memory Syndrome or Nostalgia; random scenes from a previous generation flash persistently through his mind. When the Department of Internal Security begins to take an interest in Presley’s case, he goes into hiding and a public search ensues.

Dr Sina — rejuvenated in his second or third generation and feeling financially secure but sexually inadequate — struggles to solve this difficult case, even as he deals with his own life. And through it all there is the spectre of the Long Border, separating the rich North and the violence and famine of the failed states.

In an interview with The Punch, Vassanji says that whatever he writes, his concerns reappear in one form or another. In his writings, history, memory, and identity are dominant concerns. “For a person who’s gone away from his roots, memory is of crucial importance,” says the author, whose first novel, Commonwealth Writers’ Prize-winning The Gunny Sack (1989) — the story of Salim Juma, a Tanzanian Asian and great grandson of an African slave, who is bequeathed a gunny sack by his mystical grand-aunt — had “memory” as its first word. “But the idea for a novelist is not only to remember, but to go beyond: what to do, how to cope with memory,” says Vassanji.

The author, whose identity spans three continents — North America, Africa and Asia — says that in the modern world, much of the preoccupation of the privileged and wealthy is how to live longer, how to not die. “It’s an obsession. So, moving from the mystical or religious idea of accepting death, we now desire to live forever. And my novel makes use of that,” says the author whose 1994 novel, The Book of Secrets, won the inaugural Giller Prize. He again won the Giller Prize in 2003 for The In-Between World of Vikram Lall. He is the first writer to win the Giller Prize more than once. His 2007 novel, The Assassin’s Song, was also shortlisted for Giller Prize and several other awards. Excerpts from the interview:

Nawaid Anjum: As a writer, history — or rather its neglect — has been a primary preoccupation for you. In your new novel, Nostalgia, a dystopian fiction, you explore the geopolitical consequences of forgetting the past. Tell us about its genesis and how, though set in future, it’s very much rooted in the realities of our times — generational anxiety, ethnic identity, economic subjugation or post-colonial strife?

M G Vassanji: It started very simply. Sitting on my porch one night in Toronto, feeling burdened by the past, I wondered what it would be like to unburden oneself of one’s memories, of one’s past. You can start anew, in a new land. From that the idea grew, but slowly. If you can erase the past, perhaps you can invent a new one, create a custom-made past for yourself. A new identity, for a person who can now live longer than people have lived before — forever, in principle. But who can afford such procedures? So we begin to think of the rich and the poor, the old and the young. The wealthy parts of the world and the poorer ones that resent them. We already know that in our own time, life expectancies in the rich nations are longer than in poor nations. There also comes the idea of resistance. People do resist new technologies and procedures — abortions, cloning, stem-cell, and so on. And, finally, if you can live longer and hold on to your wealth, what chance is there for the youth?

Nawaid Anjum: In your previous novels, as well as non-fiction, you have dwelled upon the complexities of colonialism, immigration and the search for identity. Do you see this novel as a departure from your previous works or do its terrains remain similar, with just a change in genre from realist to speculative? Does the shift in genre entail any change in your writing process? Do you think that despite the shift in genre, you have not really strayed beyond characters searching for their true selves against the backdrop of a world torn between here and there, a condition you have experienced yourself as a person with Indian roots living in Canada?

M G Vassanji: You’ve already answered your questions! Whatever I write — and this must be true of other writers — my concerns reappear in one form or another. History, memory, and identity are a dominant concern. For a person who’s gone away from his roots, memory is of crucial importance. (The first word of my first book happens to be “memory”). But the idea for a novelist is not only to remember, but to go beyond: what to do, how to cope with memory. Also, I did not think in terms of shifting genres. I had an idea, a speculation, and simply went ahead and produced a story. It took a long time,during which I wrote other books.

Nawaid Anjum: In a sense, Nostalgia, through explorations into memory and forgetting, depicts a quest for immortality. Were you interested in exploring the idea of immortality as a construct in fiction?

M G Vassanji: Not initially. In my upbringing, I was taught that death was something natural and inevitable. And my training in science taught me that one need not think of death as absolute — we are all part of one universe. When we decompose we simply mingle with other atoms. But in our lives now we see that we live longer and longer. The Beatles’ “sixty-four” is not considered old now. And in the modern world, much of the preoccupation of the privileged and wealthy is how to live longer, how to not die. It’s an obsession. So, moving from the mystical or religious idea of accepting death, we now desire to live forever. And my novel makes use of that.

Nawaid Anjum: For the characters in the novel, their lives are fictions engineered by some mysterious author. Did you also want this novel to be about the insufficiency of fiction?

M.G. Vassanji: I was toying with the idea of a human life story as fiction; and then of a fiction supplanting a life story — a person’s identity becoming a fiction. These are ideas that suggested themselves after accepting the initial premise: can we replace our memories with fictitious ones?

Nawaid Anjum: In the novel, the memories of people’s previous existence become a threat to their sense of reality. Did you conceive this as a political and psychological allegory?

M. G. Vassanji: I would say imagined reality rather than allegory. If you forget the past or forgo history, it will come back to torment you. Immigrants have often been told to “assimilate”. I’ve never been sure what that meant. I thought that erasing one’s memory was one way of assimilating. But we know that sometimes a single image or thought can bring back a flood of memories.

The novel gives a political edge to this idea. There is a barrier between the rich and the poor parts of the globe (remember Trump); from the poor part, the “other,” you get infiltrations of terrorists and refugees. The authorities can alter the memories of those it deems dangerous. People can do this voluntarily as a cosmetic act upon themselves. But how successfully can you do this? How many of us are from “there,” when we believe that we are indelibly from “here”?

Nawaid Anjum: The plot has shades of the paranoid fantasies of Philip K. Dick, for instance. Tell us some of the writers whose works you were reading while working on this novel.

M. G. Vassanji: I am embarrassed to say that I have hardly read science fiction. The genre seems more to deal with technology, and the weird, which I was not interested in. I read one Philip K. Dick novel and found a huge anachronism in it — a physical telephone booth in the distant future.

Nawaid Anjum: Some reviewers have pointed out that while the idea of every Canadian having the same generic past is an amusing idea, it is also a disturbing analogy for exchanging one’s heritage for that of the dominant culture. How do you see this analogy?

M. G. Vassanji: That would be a profound misreading of the book. It’s an idea from colonial times, when some misguided thought that simply by putting on accents, wearing the right clothes, and dying their hair they would become someone else. It’s also a misunderstanding of the process of immigration — the dominant culture is not static, it undergoes constant change by the infusions of other cultures. In Nostalgia, I have conceived of a future where there is no dominant culture — people invent their pasts, change their physical looks (as is already happening in our societies), and pick ahistorical names. There are of course dissenters — the religious ones who believe only God or karma determine death, those who remember ethnic identities, and so on; or the youth, who want the older people to go away and die. But they don’t, because they are not ready.

Nawaid Anjum: In the novel, as Dr Frank Sina and his patient, Presley Smith, who is experiencing nostalgia, discover, they come to understand less and less about themselves and their responsibilities to one another. Dr Frank Sina’s work also involves composing new biographies, often for the rare refugee who makes it across the Long Border. Were the global refugee crisis and the absurdities of the new regime in America on your mind while you were working on the novel?

M. G. Vassanji: No, they happened after I’d written the novel. But even as a student in the US, coming from a poor country, I had this notion — what if the poor of the world simply started walking north? In this book, I provided a logical answer: build a border. Not a simple fence, but all kinds of impediments to movement north.

Nawaid Anjum: Nostalgia is usually perceived as a “rose-tinted view” of the past. The novel, however, turns the meaning around and makes it a malady known as Leaking Memory, or Nostalgia Syndrome, which causes reminiscences from a previous life to intrude into the present one. Were you interested in subverting the very idea of nostalgia or its popular perception? Did you also conceive this as an irony — the title is certainly ironical — and satire?

M. G. Vassanji: I suppose so. The idea for the novel came earlier, and I thought long and hard about the title, aware that it could be misunderstood, especially in India, about a novel written by an NRI.

Nawaid Anjum: What are you currently working on?

M. G. Vassanji: I am exploring what it means to be an Indian, and not, in the context of some present issues in this country.

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated