Palestinian-American author Sahar Mustafah. Photos: Tamara Hijazi

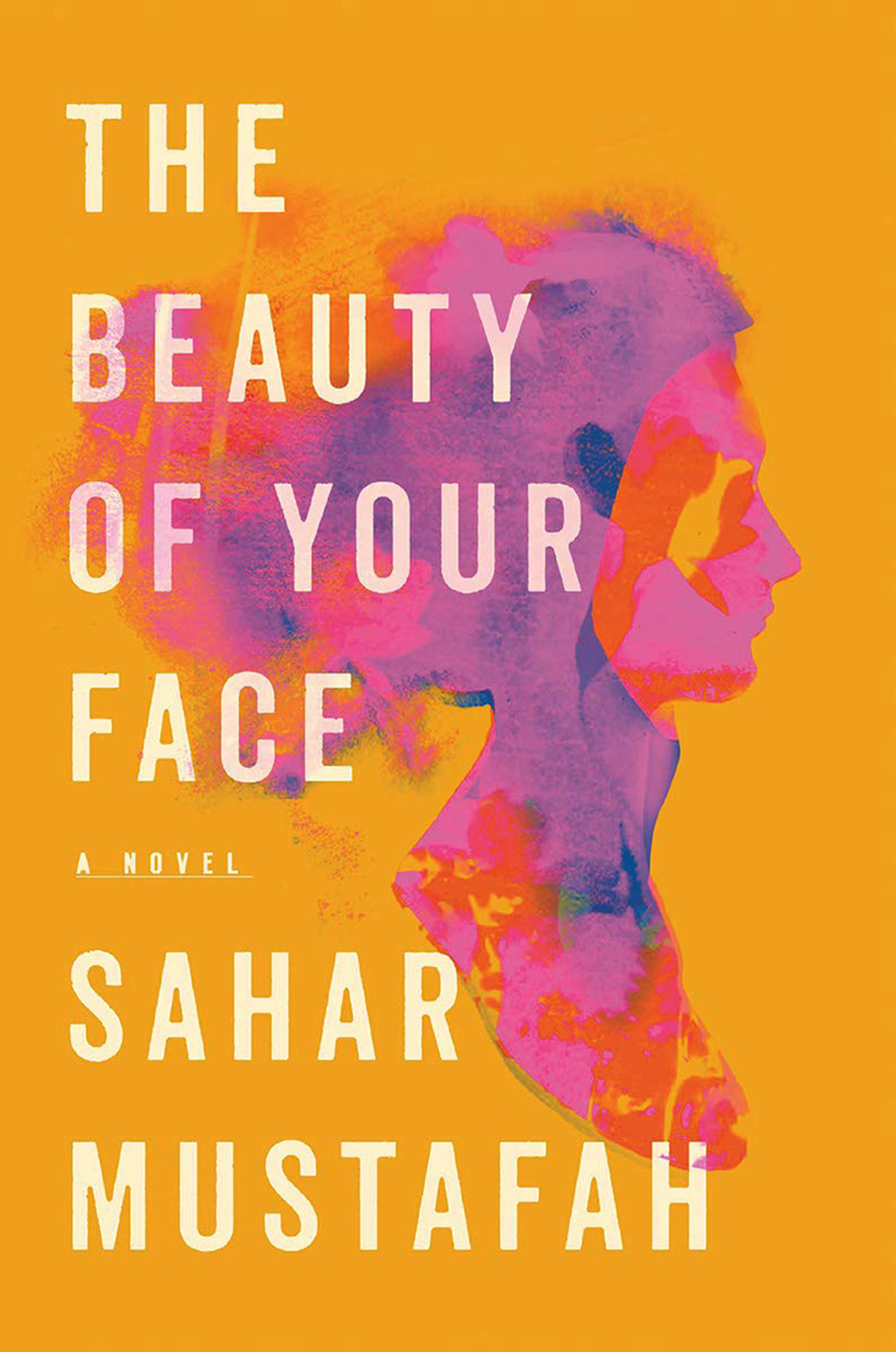

The Palestinian-American writer on her first novel, The Beauty of Your Face, in which she grapples with the horrors of domestic terrorism, growing up as an immigrant, and explores one’s identity without bending to the White gaze, championing the voices of fellow Palestinian writers without diminishing their narratives to perpetuate the American Dream

Named in The New York Times as “one of the most notable books of 2020”, and longlisted for the 2020 Center for Fiction First Novel Prize, The Beauty of Your Face by Palestinian-American writer Sahar Mustafah grapples with the horrors of domestic terrorism, growing up as an immigrant, exploring one’s identity without bending to the White gaze, and championing the voices of fellow Palestinian writers without diminishing their narratives to perpetuate the American dream. Through her novel, she hopes to invite conversations that force us to reflect and ultimately dispel existing stereotypes about Islam, and remove the burden of hope from writers of color.

A Willow Books Grand Prize Winner for Code of The West, Sahar was named one of the 25 Writers to Watch by The Guild Literary Complex of Chicago. She is also a member of Voices of Protest and Radius of Arab American Writers. Sahar’s writing is inspired by her Palestinian heritage — she is the daughter of Palestinian immigrants — which find a home in her work as a fiction writer and an educator in America.

Excerpts from an interview:

Where did you first think about your novel, The Beauty of your Face?

It germinated from the real-life hate murders of Yusor Abu-Salha, her husband Deah Shaddy Barakat, and her sister Rezan Abu-Salha in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. They were shot in cold blood by their white neighbor.

How much of Afaf’s character is taken out of your job as a high-school teacher?

It is difficult to escape the fear of a school shooting if you’re an educator in America. The chances of it occurring loom large. The details of the violence in my novel partly stem from what I’ve learned in terms of so-called training and how to prepare for an active shooter — though it’s not humanly possible to prepare for such a harrowing incident. I certainly had to imagine what it might be like to face a shooter in my building — those scenes were tough.

The novel gives us the POV of a radicalized shooter. Even though his appearance in the novel is limited, you skillfully narrate where his hate and anger originates from. It’s also interesting to me that you decided to keep him unnamed. Could you walk us through your writing process for how you chose to tackle his narration?

Thanks for noting this. Presenting a domestic terrorist required a great deal of imagination and authenticity, i.e. avoiding a stock white male shooter, so I was treading carefully as I wrote him. I avoided technical research until I could see the shooter clearly and humanly — it’s a practice in which I engage for most of my fiction writing.

Incidentally, his chapters were condensed in final editing, but I couldn’t have gotten close to him as I had to Afaf if I hadn’t written those longer chapters. I was definitely pleased with the final distillation of his character.

All that being said, as much as I humanized the shooter, I couldn’t muster the sympathy to name him. It was certainly an empathetic act to write him, but I needed some buffer, some boundary, from the violence he inflicts upon the innocent girls and teacher.

Coming to Afaf’s character, we see her mature into this strong, independent woman, who turns to her faith and ultimately finds solace in the community around her. Afaf embraces her culture and heritage instead of abandoning her religion to appease the White audience. How did you develop her character? Did it change during your writing process?

That was critical to me — to disrupt that White-gaze narrative. I wanted to present one experience of Islam as uniquely as possible, but which still might be familiar to many readers in my immediate community. I definitely accept the responsibility as a writer of color to expand the narratives around that community and not inflate stereotypes.

Afaf came to life in a second draft after an exploratory one involving multiple female Muslim American characters didn’t quite succeed. I saw her first as the principal then immediately as a child of immigrants, which I think is how I tend to see others: I’m so invested in and attracted to our origin stories and to the forces and choices bring us to critical moments in time. There weren’t technical changes in developing Afaf. It was an amazing experience following her from decade to decade, re-imagining what it was like to be invisible as a kid, then grappling with identity and belonging as teenager, and so forth.

At a time when we’re reeling from the effects of Islamophobia, and self-radicalization groups, it was refreshing to read a narrative that forced us to reflect and reject existing stereotypes about Muslims. Do you think your novel has enabled us to talk about the disturbing, unpleasant scenarios, which is sadly a lived reality for many Muslims?

I hope my novel does this, but I also deeply hope the conversation doesn’t end after reading my book. We can continue to dispel destructive stereotypes by engaging in the work of other writers, thereby expanding that conversation and avoiding a reductive telling.

Throughout the novel, you’ve resisted the boring expectation saddled on writers of color to end the story on a ‘happy’ or ‘hopeful’ note, as if their experiences could be reduced to a happily ever after. Your novel focuses, and highlights, the horror, the struggle, and the demands of growing up as child of immigrant parents, who are trying their hardest to fit in. The Beauty of your Face is as real as it gets. How did you make sure your story would stay true to its reality?

Yes, the burden of hope is one I long put down. I’ve talked a lot about this problematic expectation and how it directly manifested in my experience publishing this book. When I was querying my manuscript, I received conditional acceptance — that I drop the shooter framing. This spoke powerfully to the publishing gatekeeper’s agenda to ignore/downplay White violence and perpetuate the “immigrant narrative” which celebrates some achievement of the so-called American Dream. I’m convinced had I written about a Muslim terrorist or a Muslim-on-Muslim violence, it might have been a different experience. And perhaps it’s gendered, i.e. if I were a male writer, my manuscript would be readily accepted and considered more edgy. It’s also very compelling to me that most white audiences are able to easily consume violence inflicted upon Bipoc communities — “trauma porn” is the term I’ve heard used to describe this phenomena —but find it harder to swallow such violence committed by members of its community. In my case, it’s one story of America revealing the fractured and disparate experiences of many of its citizens.

Growing up in a field heavily dominated by White people, and considering the content of your novel, how much of your work were you able to retain during the editing process. How did the publishing field react to your book?

Once I signed with my agent, the manuscript was relatively quickly sold at auction to W.W. Norton. My editor, who read it in one sitting, is a poet and I’m grateful for the close attention and care she gave my work. We had valuable and critical conversations about what worked and what needed revision. There wasn’t any aspect that I felt was sacrificed. I learned a great deal about the revision process and how good editors will guide my story to its full potential without it turning into something I don’t recognize.

To what an extent has the terrain of your writing been shaped by your experience of having been raised by Palestinian immigrants? What does your writing process look like and how long did it take you to write The Beauty of Your Face?

It’s inevitable that parts of myself and my identities have seeped into the writing of this book and most of my work. Over twenty years ago, I began from a place of deep yearning for stories that reflected my lived experiences and my community. This desire essentially informs my writing: I compose stories I wish had been available to me all those years ago. It feels like I’m filling a void alongside other talented Palestinian and Muslim American writers. With that comes a sense of gratitude and responsibility.

I tend to write quickly once an idea takes off. I spent approximately two years on The Beauty of Your Face. Generally speaking, I begin writing when a character and situation come to me then move in and out of a journal to flesh out setting and plot, and for technical research. Each project has its own journal. With my full-time teaching schedule, I wake up very early to write since it’s the best time for my creative brain to go to work.

Could you give us a sense of the literature being produced by Palestinian writers, both those living in Palestine and its great Diaspora?

It’s an incredibly exciting time for Palestinian writers. In 2020, six writers, including myself, launched books which included debut poet George Abraham and novelist Zaina Arafat, critically acclaimed author and activist Susan Abualhawa, and Adania Shibli whose translated novel was named a New York Times Book Review Notable Book of 2020. Susan Muaddi Darraj also launched a middle grade series featuring the first Palestinian American girl as a major protagonist. The list continues this year with a highly anticipated memoir from Randa Jarrar. This all testifies to the existence of a vibrant Palestinian community of writers who steadily infuse mainstream publishing and reach wider audiences.

Please don’t mistake my point: this community has always been here. We’re finally gaining more visibility and attention as publishing becomes more diversified and open. Hopefully, we’ll continue to expand our narratives and diminish tokenism and exotification. The scope of our work is quite broad and our content is compellingly nuanced and diverse even as it speaks to the familiar trauma of displacement and landless-ness, and the perpetual search for home. Some of our work addresses what it means to be born away from a native homeland and its implications; others celebrate our American-ness, despite its fractured nature. We also explore the politically fraught identity of being Palestinian along with our identities of sexuality and gender. I’m happy to declare you’ll find it difficult to pigeon-hole us.

Are you currently working on a novel?

I’m working on a few projects at the moment. I do hope I can follow up The Beauty of Your Face with another novel soon.

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated